All your life you count on the world to work in a certain way. Then you go to Japan.

I’d only just arrived and had barely figured out how to get some yen out of the airport ATM and make it onto the subway when there it was: a freakishly oversized can of Pepsi in the hands of a Tokyo teenager. There are only a few fixed, eternal qualities you can count on in this world, and a twelve-ounce soft drink is one of them. It’s one of the two-by-fours we hang the sheetrock of our reality on, and when it turns into a three-by-eight, where are you? In Japan.

Why were people wearing surgical masks in public? Why were they hitting golf balls on the roof of that twelve-story building? Why was there such an unearthly quiet on the subway at evening rush hour? Why were these nice people handing me free packets of tissues on the street corner? Why did the toilets have four color-coded buttons? Why were the streets picture-perfect clean when there wasn’t a public waste can in sight? And, for that matter, why were there no public waste cans? Did all the people in Tokyo carry their gum wrappers around all day until they got home?

But my most pressing why that first night in Tokyo — once I had absorbed the ontological body blow of the wrong-sized Pepsi can, and emerged from the subway amid an eerily quiet tide of humans in surgical masks, and navigated Ikebukuro Station’s twenty-seven separate exits, and made it past the nice people with the tissues, and checked into the ryokan (Japanese hostel), and tried to use its toilet without launching a strategic missile strike, and headed back out onto the preternaturally clean streets to do something about my nasty hunger pangs — was: Why won’t you take my perfectly good yen and give me one of those lovely bowls of noodle soup?

The man behind the counter at the tiny noodle shop smiled and nodded and held up a little card with a picture of the lovely noodle soup I wanted to eat, but he wouldn’t take my cash, and he wouldn’t give me the soup. He wouldn’t even give me the little photo of the soup. “Sorry, sorry,” he said, and, still smiling, pointed me toward the door.

The place was spotless and brightly lit with fluorescent fixtures, a tiny sink at one end, a TV at the other. A smiling ceramic cat sat on a shelf, its raised paw also seeming to point me to the door. There were ten stools in the place and five customers. No one spoke. Aside from some prodigious slurping, each patron was quiet.

“Do you want,” said a voice behind me, “to purchase Japanese noodle?”

I turned around. One of the noodle slurpers, a shy, middle-aged man, nodded at me. It was almost a bow.

“Very much,” I said, nodding back. “Or any kind of noodles, actually. Please tell me how much.”

“He cannot accept your money.”

And, as if to underscore the shy man’s point, the smiling man behind the counter again pointed to the door.

“I’m sorry,” said the shy man. (Why is everyone so sorry?) “You, ah . . . must go . . .” And then he, too, pointed.

There I was, jet-lagged and famished, being shown the door by two of the most polite people I had ever met. And a smiling cat.

“You must go,” said the shy man, “to get a ticket.”

And then I realized he wasn’t actually pointing to the door but to a machine just inside the door. It had matchbook-sized buttons, each sporting nearly identical pictures of noodle soup. A new customer had just come through the door, and I looked over his shoulder as he inserted various coins and bills and then punched buttons. Out came a ticket with a photo of soup on it, just like the one the man behind the counter had held up. In Japan, it seemed, you couldn’t buy a bowl of soup without first buying a vending-machine photo of that bowl of soup. Was this a better way of doing things? I didn’t know, but I got my soup.

This visit to Japan was my first stop on a four-month journey to see the world. I’d expected Japan to be clean, well-ordered, and technologically advanced, and it was. I’d also expected it to be different from the U.S., to have its own ways and eccentricities. But I hadn’t put the two together. Here in Japan I found advanced technology implemented by a starkly different civilization. At first blush the result felt like a futuristic sci-fi movie, as much utopian as dystopian.

You’re not here for the future, I kept telling myself those first few evenings, after I’d fallen back to my little room at the ryokan like a shellshocked soldier to his bunker. You’re supposed to be on the first leg of a global pilgrimage. Japan is the homeland of Zen, remember? That’s why you came.

I’d spent a fair portion of my youth puzzling over koans, reading Alan Watts and D.T. Suzuki, and being beguiled by Zen masters and their oblique stories of enlightenment. These masters spoke of a mysterious emptiness at the heart of Zen, a “marvelous Void.” I’d had my share of run-ins with a spiritual void in my twenties and thirties, though I would hardly have called them “marvelous.” Rather these run-ins were filled with more terror than wonder. Do not stare too long into the abyss, Nietzsche warned, or the abyss will stare back into you. But I failed to listen. Seeking explanations, I made a few efforts at organized religion, but nothing clicked. Until I stumbled upon Zen. It was the unreligion. Fearless yet playful. Dada, but with discipline. These Zen masters kept a spring in their step, even chuckled as they walked along the lip of the abyss. Zen spoke to me. Unfortunately I was a bit hard of hearing.

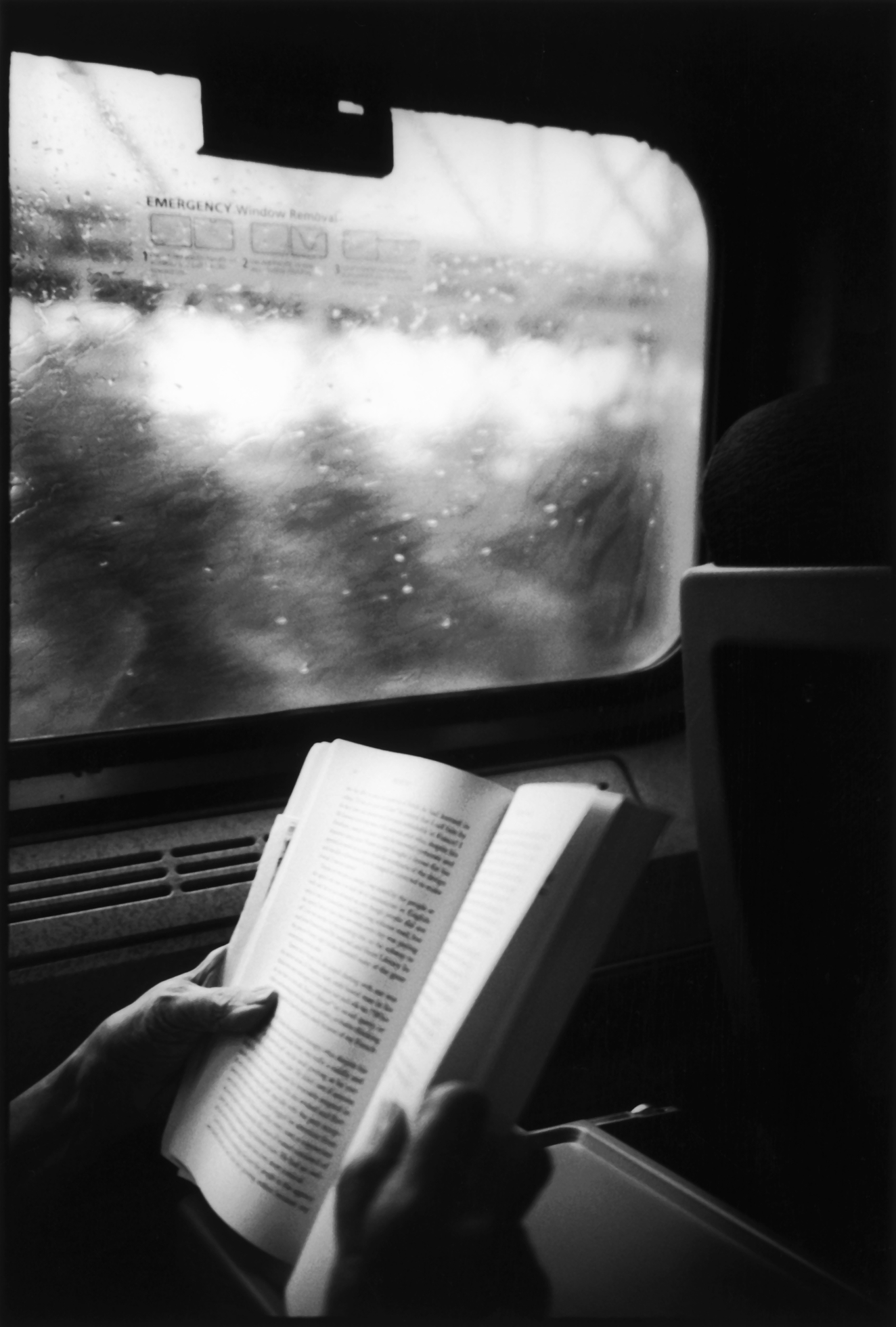

I’d brought with me several slim Zen volumes, and as I lay in my small, cold room at the ryokan, I read them again. “You must let the cloth weave the cloth.” “What was your face before you were born?” I guess I was hoping these koans would make more sense now that I was here in Japan, that maybe just the air, or Japanese gravity, or the spare lines of my room might inch me a hair farther down the path to satori (enlightenment). Not a chance. As always, the koans were utterly baffling — as they were designed to be. Clearly I was going to have to do more than just show up.

In one of my favorite parables a university professor, curious about Zen, comes to visit Master Nan-in. They sit down for tea. The monk quietly pours his visitor’s cup full, then keeps on pouring. The professor watches the cup overflow until he can no longer restrain himself. “It is overfull!” he shouts. “No more will go in!” And then — wait for it, the moment when the master teaches the foolish “grasshopper” a lesson: “Like this cup,” Nan-in says, “you are full of your own opinions and speculations. How can I show you Zen unless you first empty your cup?”

Was Tokyo filling my cup or emptying it? I wasn’t sure, but these Zen stories charmed me. I trusted them (though the skeptic in me wondered where the masters kept finding such willing foils). There is something wonderfully absurd about Zen, and something gravely humble as well. It refuses to declare truths or even define itself. Instead, via parable, logical conundrum, or the simple command to sit, breathe, and pay attention, Zen throws you back upon yourself and the “suchness” of everyday reality.

But did I really want to be thrown? If that’s why I’d come to Japan, shouldn’t I have been in Kyoto, meditating in the famous gardens of the Ryōan-ji temple? If I’d come to visit the Zen homeland, shouldn’t I have been hiking on the island of Shikoku, walking the traditional eighty-eight-stage circuit from temple to temple? Or at least popping off to the sacred sites at Nikkō or Kamakura? Yes, but I kept putting off these little pilgrimages. Zen may have charmed me, but it frustrated me too. More than this, it scared me. It made me feel as though I were chasing my own tail — and if I ever caught it, what then? I’d be staring back into my own blank stare, with no idea what to do. So, instead of Nikkō or Shikoku or Kamakura, I flung myself at Tokyo day after day.

“New York with five Times Squares” was my first stab at trying to describe this city of massive neon caverns. A day later it seemed more like Los Angeles — a huge, decentralized city — but with subways. (Maybe LA would have been more like Tokyo if General Motors, Firestone, and Standard Oil hadn’t ripped out the cable cars in 1946.) Two days later it was the capital of a feudal kingdom with 1,500 years’ worth of crooked alleyways that had been firebombed into oblivion and rebuilt in a hurry. Or perhaps it was a sprawling Japanese Vegas, minus the desert. Or a fever dream.

Looking for a bathroom one afternoon, I stepped into a downtown cafe, and suddenly I was in France — brioche, croissants, café au lait, little marble tables, wire chairs — but all the customers were Japanese. The next evening it was Italy — a traditional ristorante faithfully re-created down to the Venetian plaster and rococo furnishings — and the evening after that a fellow from the ryokan and I headed to an English pub in the Kabukichō district. Passing through a nondescript door and down a set of stairs, we entered a bar with dark wood banisters, framed oil paintings, and a dartboard. They’d gotten everything right, down to the coat of arms on the wall and the two fine pints of Bass ale we ordered.

It is a canard of postmodernism that the replica is “more real” than the original. (In Disneyland, the Wild West experience is re-created not from actual artifacts of frontier days but from memorabilia of Hollywood westerns.) In Tokyo not only were the copies more real; they were bigger and better. The Tokyo Tower, a huge radio tower built in 1958, is a near replica of the Eiffel Tower, but thirteen meters taller. Americans have done the same in Vegas, with Paris next door to the Roman Colosseum, which is just down the Strip from the Egyptian Pyramids. But in Tokyo it was harder to tell where the real culture began and the copy left off. Baseball and Kentucky Fried Chicken seemed as Japanese as sushi. In one KFC a twenty-something Japanese woman wanting to practice her English struck up a conversation with me. “Do you have also Kentucky Fried Chicken in America?” she asked. Tokyo was a Vegas people actually lived in, then forgot was Vegas.

But the Japanese weren’t the only ones who’d confused the copy and the original. It was impossible for me not to experience Tokyo through the lens of all the media images by which I had come to know it over the prior forty years. Looking out the window of the subway, I’d see a bridge and a river and a kanji-lettered chemical plant and wonder when Godzilla was going to turn it all into a B-movie lake of fire. The Imperial Palace grounds, with their impressive shogun-era fortress walls and towering wooden gateways, seemed wrong without Toshirō Mifune in samurai garb, playing the lead in a Kurosawa epic. “The sky was the color of television,” reads the opening line of William Gibson’s science-fiction novel Neuromancer, as the protagonist drifts through the streets of Tokyo. And so it was my first few nights in the city: rainy and gray, the neon lights reflected in a dome of overcast sky. The Blade Runner set, depicting a dystopian Los Angeles of 2019, was inspired by contemporary Tokyo, with its dark, narrow alleyways and towering electric billboards.

Preconceived notions are bad, I told myself. I shouldn’t let my expectations get in the way of experiencing the place on its own terms. But it was the images and ideas already rattling around in my head that made Tokyo come alive out of the neon and drizzle. Like the rest of the backpackers at the ryokan, I’d always figured the best way to travel was to avoid the tourist traps and seek out “authenticity” — some kind of purer, more “real” experience of the local culture. But in Tokyo, with the real and the imitation already so confused, what did that even mean?

On the evening of my third day in the city I found myself swapping stories with a mix of Swedes, Italians, and Australians in the ryokan’s tiny kitchenette. It quickly became apparent that we were all collecting a similar set of odd, ironic encounters. I told them my noodle-soup-ticket story; they told me theirs.

“Dude,” said an American who’d been standing by the tea machine, eavesdropping, “they just don’t want to touch the money. Not all Japanese restaurants are set up that way.”

“Actually, I figured that one out myself,” I said. “That’s half the point of the story.”

“But you say it like it’s some kind of great revelation.”

His name was Troy. Tall, mildly handsome, late twenties. He was wearing the same Swatch-brand watch I’d seen most Japanese men his age wearing. He’d been living in Japan for a few years, one of the Swedes had told me, and seemed to harbor a special resentment for American visitors like me.

“Did someone get up on the wrong side of the tatama mat this morning?” I asked.

“It’s a tatami,” he shot back, “and I hope you slept on the futon on top of the tatami.”

The guy had gotten my New York hackles up. “Dude-san, if you know everything already, why are you staying in the ryokan with the rest of us newbies?”

“Look, you’re an American, right?”

“Uh-huh.”

“You’ve been here, what? Two days?”

“Three.”

“Three days. I’ve been here three years. I’m not saying I know everything, but I know enough to know that there’s a lot I don’t know.”

“That’s very Donald Rumsfeld of you.”

That got a chuckle out of him, and we both eased up a little. He’d been living far to the south in Kobe and was visiting Tokyo like the rest of us. He’d taught English for a year, then stayed on for another two. His Japanese was good. I couldn’t tell what his current job was or if he even had one, but, despite his pretensions, he seemed quite homesick.

“If you’re here for ten days,” he went on, a bit despairingly, “you think you understand the place. If you’re here for ten years, you might actually begin to understand it. Anything in between and you’re lost.” By his own metric he was lost, and so was I — but, crucially, I didn’t know it yet.

“So you’re saying I’m too happy?” I asked. “Or just clueless?”

“Yes.”

“Well, bully for me.”

But, as I walked away, I knew he was right. It took Eugen Herrigel, a German studying Zen archery in Japan in the 1930s, a full five years simply to learn how to release his bowstring “unintentionally.” I was a voyeur, a dilettante, a drive-by gleaner. I was passing through Japan without enough time to learn the language or properly settle in. And I was making up for it by jumping to conclusions and turning ordinary encounters into defining moments.

Culture shock, according to the literature, comes in phases, and I happened to be in the honeymoon phase, when everything about the foreign culture is romantic and new. Who needed to go on a Zen pilgrimage? Hadn’t I already slipped into a kind of backpacker’s “beginner’s mind” (the mental state prized by Zen for its innocence and openness)? As I flitted about Tokyo’s urban attractions, the entire society felt like a novelty act prepared just for me. I took money out of ATMs in small amounts not only to keep my spending down but also to return again and again to see the little blue space dog do his cute “transaction complete” somersault on the screen. A punked-out teenager on the street corner singing early Beatles songs? Sweet innocence in a mohawk. The three-foot-tall Godzilla statue? Disappointing, for sure. Hell, I’d thought it was going to be hundreds of feet high. But once I’d gotten over that, oh, so cute, because, well, I was on a honeymoon with Japan! Comic-porn lending libraries? Strange, but maybe my kind of strange. Four-hundred-pound sumo wrestlers knocking bellies with great reverence for the ancient Shinto gods? Incredible!

To a New Yorker the Tokyo subways were a marvel of urban planning and social discipline. No graffiti, no vandalism, no crazy people, no chewing gum stuck to the floor, hardly any dirt or dust, even. Commuters dutifully queued up at marked spots on the platform before each train arrived: Heated seats. Route maps on flat-panel video displays, updating in real time the number of minutes to the next station. Teardrop-shaped ceiling straps, more charming — and more plentiful — than those on New York subways. And everyone quiet, everyone polite, everyone Japanese.

There is hardly any crime in Japan. National pride, social responsibility, and customer service are like secular religions. I had the unmistakable feeling that if my wallet had happened to fall out of my back pocket, it would have found its way back to me within the day, sealed in a zip-lock bag with a full accounting of its contents and an apology that chance or circumstance or sly gravity could have possibly conspired to separate me from it during my short stay on Japanese soil.

According to the books, this high wouldn’t last forever. If I stuck around for another month, I’d cross over from the honeymoon phase to the critical phase: Anxiety, irritation, disgust, mood swings, and depression would be the order of the day. The subways would become dystopian experiments in social control, the comic-porn lending libraries my only refuge. After a full six to twelve months of this, I’d finally reach the adjustment phase, when I would develop a balanced view of the culture, both good and bad.

But why stick around for that when right now every day in Japan was like a trip to Disneyland? My Zen quest beckoned, but so did the two-million-square-foot Tsukiji fish market, the largest in the world, with sea creatures from every ocean on earth — and, by the look of them, several other planets. I imagined these seafood items crossing my path later in the day at an elite sushi bar or, more likely, a grungy subway luncheonette, where they’d poke along a countertop sushi conveyor belt. Or it might not be a sushi restaurant at all. It might be a restaurant serving a subset of Japanese cuisine — tonkatsu, shokudo, kushikatsu, shabu-shabu — previously unknown to me.

I am not a “foodie” or much of a shopper, but Tokyo made me want to become both. I felt dangerously happy simply wandering through the ITOYA stationery store — five stories of finely gradated pastel writing paper, individually wrapped greeting cards, and every possible device humankind has devised for attaching one piece of paper to another. I was giddily lost among the complex of stores in the Akihabara “Electric Town” district, a city within a city of stores selling gadgets and appliances and cellphones. Or the Matsuya Co. and Matsuzakaya department stores in the Ginza district: ten stories of elite restaurants, markets, clothing, furniture, and more. For years I’ve been an eco-activist, and one of my mottoes, borrowed from the 1968 student revolts in Paris, is “The more you consume, the less you live.” But now I thrilled to the spectacle of consumption. I rarely bought anything (besides lunch), but I feasted my eyes on this endless pageant of high capitalism, this otherworldly display of opulence. I was dazzled by its sheer lavishness, its thrilling otherness.

After almost a week it seemed that Tokyo was overfilling my cup, not emptying it. I had set aside the thin volumes of Zen wisdom. Each evening I’d return to my room at the ryokan and slip into a Murakami novel set in a dreamlike Tokyo. On the eve of my last weekend I stayed up till 2 AM to finish the book. Closing the cover, the dreamy prose already receding in memory, I looked around my monk’s cell of a room — and the room mocked me. Like the Zen teacher I did not have, it whacked me in the head. In the homeland of Zen I’d squandered my time on a shopping binge in which I hadn’t even bought anything. I lay there, the cold of the concrete floor penetrating the thin bedding, and admired the lines of the plain wood ceiling. The room was spare, simple, graceful. It reminded me of the promise of Zen — not transcendence or some grand theosophy or even happiness, but simple acceptance of one’s own humanity. And in that moment it was promise enough. I’d missed my chance to go to Kyoto, but I could still take a day trip south to Kamakura, Japan’s thirteenth-century capital and religious center. It was time to go on pilgrimage.

The word pilgrimage calls to mind a long journey beset with hardships to consecrate one’s faith, but the air-conditioned train ride to Kamakura the next morning took just fifty-six minutes. The sun was out when I arrived, the sky a beautiful blue. Zen had till sundown to catch me unawares.

From the train station I walked into town, past a Wendy’s, a Burger King, and a string of traditional shops selling sake and dried fish; then I continued out of town again, past stands of trees and scatterings of modest homes, until I reached Kamakura’s most famous site, the Great Buddha, cast in bronze and weighing in at more than a hundred tons. The temple it was once housed in had been washed away by a tsunami in 1498. Ah, impermanence, I thought as I gazed up at the Buddha’s serene five-foot-wide brow and tried to imagine the now-vanished temple. I paid my eighty yen and walked inside the hollow statue. Here was emptiness, for sure.

With only a few low-wattage bulbs for light, the space was dark and a few degrees warmer. There was something plainly comical about being inside the belly of the Buddha, and yet reverent too. The hollow echoes and the earthy smell of slowly oxidizing metal made me want to sit and meditate right there, not get up for days, not eat, not shower, let my hair mat together until, in the silent, empty womb of the Buddha’s belly, I became enlightened. Unfortunately the belly was neither empty nor silent. Tourists filed in and out at an alarming clip. I’d expected to run into other Western tourists in Kamakura, but these visitors were all Japanese. They’d step inside just long enough to take a few photographs, exchange remarks with their companions, and sheepishly rap on the Buddha’s bronze insides. Then they’d be off to the next sight or temple. Weren’t they the same tourists I’d seen chattering on the south observation deck of the Empire State Building? They were wearing the same Japanese leisure wear and loaded down with the same cameras. I had nothing against Japanese tourists, but what were they doing in Japan?

Next I went looking for a temple that was still standing. There were many to choose from. The first one I came across was Shinto, not Buddhist, its entrance guarded by statues of wild-eyed demons. The next was mobbed by a troop of schoolgirls. I struck off in a different direction and climbed a wooded trail to a hilltop shrine. The view was lovely, but right next to the shrine was a tea shop — and the prices were not cheap. What had I expected: an eternal spring of green tea spouting from the rock? A Zen master waiting to instruct me — and only me — in the art of the tea ceremony?

I had nobody to blame but myself — well, and Zen of course. Going to a place to try to have a certain feeling, especially a Zen feeling, is a decidedly contrarian enterprise. Zen, says Alan Watts, “is a traveling without point, with nowhere to go.” It exists only in the moment and, as such, must take you by surprise. But how, I wondered, sitting there glumly in the tea shop, can you plan to take yourself by surprise? This mystery seemed as much a paradox of foreign travel as of Zen itself.

I decided to head for the Zuisen-ji temple, the remotest, most secluded of all the Zen temples in Kamakura, and — if it wasn’t overrun by schoolgirls, Shinto demons, or camera-happy tourists — just quietly sit in the gardens there, which were supposed to have been designed by the temple’s founder seven hundred years ago. I cut back through town again, passing a library, a small electrical plant, and a souvenir shop selling everything from samurai swords to candy. A little turned around by this point, I came across a park by a small lake. Couples were sitting on benches, and families were picnicking. The schoolgirls were there in their blue-and-white outfits, giggling to each other. At the edge of the water dozens of vertical white banners on bamboo poles caught the wind as if this were a scene out of the movie Ran, minus the horsemen. Hundreds of prayer messages, calligraphed onto little white strips of fabric, festooned a nearby Japanese maple. A middle-aged couple were adding their own to a low-hanging branch. I stopped to take a picture.

“Excuse me,” said a voice behind me. One of the schoolgirls had crossed the lane to talk to the American tourist. “What do you think of Heian style of architecture?”

“Well,” I said, “to be honest, I don’t know a thing about the Heian style of architecture, but can I ask you a question?”

“Certainly.”

“Is this a Buddhist festival today in the park? Zen Buddhist?”

“Yes. Well, no.”

“No? So, Shinto?”

“No. Yes. Please, a moment . . .” She swiveled out the keyboard on her cellphone, and her tiny fingers tapped away. A few of her friends crossed the lane and joined us. She held up the cellphone, and it talked to me. “PAN-THE-ISM,” said the pink cellphone in a girly robot voice. The schoolgirl nodded and smiled. By now the entire troop had joined us.

“Please take picture?” they asked. Which meant, it seemed, Please let us take a picture of you with us. Which I did, and for a few precious minutes I was the envy of middle-aged schoolgirl fetishists the world over. When we were done, I asked them to point me in the direction of the Zuisen-ji temple.

“Grasshopper,” said an American voice as the girls waved goodbye, a disturbingly familiar American voice. I turned around. It was Troy.

“I never get lost,” he continued, in his Zen-master voice, “because I don’t know where I’m going.”

“That’s very helpful. Thank you.”

“Master Ikkyū. Fifteenth century.”

“And what are you doing in Kamakura, Troy?”

“I’m being a tourist this week, like you.”

He had a knapsack slung over his shoulder and was still wearing that red Swatch.

“I thought you had a strict antitourist policy.”

“And, for a moment there,” he said, “I thought you were a lolicon.”

“A what?”

“Lolita complex. They call it ‘lolicon’ here.”

“Nope. Guess again.”

“A Zen complex?”

“Bingo.”

“Nobody practices that anymore. Try going to a Zen temple in this country.”

“That’s exactly what I am trying to do.”

“Well, it’ll be empty. And half the time it’s not even a Zen temple. And even when it is a Zen temple, it’s not Zen really.”

“That all sounds pretty Zen to me.”

“Look, I know you’re enamored of the country, and I don’t want to burst your bubble, but have you really looked around? This is a consumer empire, just like America. They’ve destroyed their own culture and nearly everything that’s beautiful about it.”

“What do you call this then?” I asked, gesturing to the tree with the prayer messages tied to its branches. It was even more beautiful now, lit by the sunlight reflecting off the surface of the lake.

“All those messages are prefab. They’re like Zen Hallmark cards. Not even. They’re like superstitious Hallmark cards. That salaryman and his wife over there? They’re just buying superstitious greeting cards and tying them to that tree.”

That shut me up for a bit.

“Ride the subway in the morning — the early morning,” Troy continued. “Everyone’s just beaten down. Sardines. Automatons.”

“C’mon, it’s not that bad. I saw a whole mess of punked-out goth kids on the street the other day.”

“Sure, I know the three Tokyo street corners you’re talking about. But did you see that anywhere else? Did you see any of them here? It’s a country of 130 million, and those are the rebels. That’s it. You’ve seen every single one of them.”

We started walking in what I hoped was the direction of the temple.

“It’s all Valley of the Dolls. You’re seeing a Potemkin village of what you think Japan is. Zen’s mostly kitsch here. Rape is ridiculously high. A single girl can’t answer the phone without hearing heavy breathing. And don’t get me started on the discrimination. Third-generation Koreans don’t even have citizenship yet. And sure, everyone thinks Japan is an efficient culture, but it’s only true when it comes to a few things. Have you been to the hospital? Have you tried to cash a check around here? It takes twenty minutes, minimum. China is going to eat Japan for lunch. When it’s all over, this place is going to be nothing more than a little tea shop selling Zen trinkets.”

And, right on cue, there was a little tea shop selling Zen trinkets. In the window: Divination sticks. Wooden votive plaques. Whisks and iron pots for the tea ceremony. I had to get out of there before I lost what was left of my Zen will. “Troy-san,” I said, giving him a mock bow, “it’s been an experience, but now I have to find a nice quiet temple garden to meditate in, even if it’s the last one in all of Japan.”

“You’ll want to hear about the schoolboy’s thumb, then.” And before I could stop him, he launched into the parable of Zen master Gutei. It was obviously one of Troy’s favorites, and he had his own, somewhat dubious version of it, but the core story is this:

Gutei is a Zen master who answers all questions about Zen by holding up one thumb. One morning, when the master is away, a visitor asks his young attendant, a schoolboy, about the meaning of Zen. The boy holds up his thumb in imitation of the master. When Gutei hears about this, he calls the boy to him and pulls out his sword and slices the schoolboy’s thumb off. The boy wails in pain and surprise, and, clutching his gushing hand, runs away screaming. The master follows, shouting, “Wait, wait!” Eventually the boy turns around. “What?” he cries. The master once again holds up his thumb. The boy is instantly enlightened.

I don’t believe this is too many people’s favorite Zen parable. Still Troy told it to me as if he were bestowing upon me a great privilege. I’d heard stories of Zen masters’ apparent cruelty before, but this was more horrific than most, and more confounding.

After a mix of right and wrong turns, I found the country road I needed and made my way to the Zuisen-ji temple. The grounds and garden were beautiful, serene, and spare: stones, moss, a pool of water. The peculiar geometry was meant to conjure a “controlled accident,” collapsing the dualities of chance and design, nature and the work of the human hand. Stones picked by the sensitive eye of the Japanese rock gardener are ranked among Japan’s most precious national treasures. We have Plymouth Rock; they simply have rocks. I sat down near these national treasures, lowered my eyes, focused on my breath, and followed the instructions I’d been taught years before.

It may have been quiet and pleasant in the garden, but it was nothing but ugly and noisy in my mind. Equanimity? Lovingkindness? Not so much. These qualities, of course, take years to cultivate, but I would have been happy that afternoon for the slightest quieting of the din inside my head. Instead it was as if the silence in the garden were a vacuum that my mind abhorred. My thoughts churned through a noisy mishmash of politics, movies, women, and whatnot: I thought of my cellphone back in New York and who might be calling it. I went over the things I could have said differently on a right-wing radio show I’d been on months earlier. And I kept circling back to Troy’s story of the severed thumb. It was as if he’d deliberately planted his visceral and disturbing koan in my mind for this occasion. It felt so right and so wrong all at the same time — not just opaque but morally suspect. The only void I was getting in touch with here was a void of meaning. A bloody, mutilated void of meaning. Where was the marvelousness?

When I returned to the ryokan, the concierge handed me a note. It was from Troy. He’d checked out earlier that evening. “Nikkō,” the note said. That was all. Just the name of another of Zen’s sacred sites. Still bossy, even on the page. I was dispirited and didn’t like being told what to do, but I was determined to try (or, actually, not try) again. And so, the next morning, with as much purposeless purpose as I could muster, I headed to Nikkō, two hours north by train and a few thousand feet higher in elevation.

It was January. It was cold. I had packed for Thailand and India, not for Japanese mountains in the winter. At the railroad station, however, they were expecting me: a store selling hats and gloves to foolish pilgrims. I stepped in to check the prices and warm up a little. Too expensive for one-time use, I decided. Or was it pride? Anyway I was supposed to be on a pilgrimage: why not rough it a little? I zipped the collar of my windbreaker over my chin, pushed my hands into my pockets, and set off for the long walk to the forest shrines. Every block or two I had to rub some warmth back into my ears. It began to snow.

At the edge of town a wooden bridge arched over a stream and into the forest. Warrior demons and great iron-studded gates guarded the entrance to the sanctuary grounds. There were few visitors there in the off-season, and beyond the gates to the forest it was quiet. Nikkō has many temples and pagodas, but the architecture didn’t move me. It was the forest; it was the quiet. It was obvious why this had been a sacred Buddhist site for more than a millennium. You could feel it. There was an interiority to the forest, a layering of quiet. The temples; the forest; you. And the snow, yet another layer, placing a hush on everything, taking you one step farther inside. I shivered. I lingered there by a shogun-era drum tower, its flared roof dusted in snow, a stand of cedars rising above it.

I was struck by the beauty, struck so hard it hurt. I shuddered, and I knew I would remember this scene my whole pre-Alzheimer’s life. Maybe this was wabi, the feeling Zen calligraphers strive to illustrate, the emptiness from which one glimpses the beautiful suchness of something ordinary. I stood there for a long while, watching the snow fall between the timbers, everything just so.

Nikkō’s hush stayed with me on the train ride back that night and was still with me hours later on the Metro, mirrored now by the subway’s own well-ordered quiet.

On my last morning I packed my bags for the airport and headed downtown for one last run-in with Tokyo.

The wrong-sized Pepsi can of my arrival seemed forever ago. I knew now that the smiling cat that had wanted me gone from the noodle place had actually been welcoming me. It was a Maneki Neko, a talisman of good fortune, its raised paw beckoning customers and money in the door, a motion done in Japan (confusingly for us Westerners) with the palm turned outward. Other bewilderments of that first evening had also shaken out their secrets: The tissues handed out on the street were advertisements; the surgical masks, a public-health courtesy worn by those nursing colds. Public waste cans had been removed from the streets in the wake of the Aum Shinrikyo terrorist attack for fear that bombs might be left in them. I’d figured out the buttons on the high-tech toilet, too: one controlled the temperature of the toilet seat; another, a bidet-like sprayer; a third, a postbidet blow-dry feature. The last button switched on an audio track of a flushing toilet, which confused me at first, as it was labeled a “water-saving” feature. It seems that many Japanese women are embarrassed to have others hear them urinate and, prior to this innovation, flushed public toilets continuously to cover the sound of their bodily functions, wasting a large amount of water. Thus the audio-track button, which produces the sound without the actual flushing. All of which was about as insane as it was perfectly understandable.

We travel to encounter otherness. We travel to be surprised, amazed, perplexed, challenged, even disgusted by people who, like us, have two arms and two legs and love and pray and eat and shit, yet order the world differently. Maybe they’re asking the same questions about how best to prevent terrorism, serve food, or conquer duality, but they come up with different answers: Remove all public waste cans. Noodle-soup tickets. Zen.