THE UNITED STATES HAS THE HIGHEST PRISON POPULATION OF ANY COUNTRY IN THE WORLD, with 2.4 million people behind bars. When you include those on probation and parole, more than 7 million people are bound up in the U.S. correctional system. That’s one in thirty-one adults. Many people acknowledge that the prison system is growing too fast and needs reform, but journalist Maya Schenwar goes farther. She believes that modest changes, like making parole less restrictive or shortening excessive sentences, are important but insufficient. The ultimate goal, she says, should be to abolish prisons altogether.

In her book Locked Down, Locked Out: Why Prison Doesn’t Work and How We Can Do Better, Schenwar argues that mass incarceration is intrinsically harmful and doesn’t solve the problem of crime or make us safer. Using extensive research and the experiences of people whose lives have been upended by the prison system — many of whom she interviews — she shows that putting people in cells doesn’t rehabilitate them, and it destroys families and communities. Schenwar goes on to describe alternatives to mass incarceration, drawing examples from other countries, small-scale experiments, and the ideas of prison reformers. She doesn’t advocate simply opening the cell doors but makes a case that other, overlooked possibilities exist for addressing violence and minimizing the harm we do to each other.

Schenwar grew up in Chicago, the daughter of public-school teachers with a strong social-justice ethic. Her great-grandfather was a member of the Communist Party, and her grandfather was investigated by notorious anticommunist Senator Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s. Schenwar traces the origin of her long-standing interest in the prison system to her mentor, Kathy Kelly, founder of the direct-action group Voices for Creative Nonviolence. Kelly, who has been arrested and jailed dozens of times for civil disobedience, spoke at Schenwar’s high school and inspired the teenager to see prison as a destructive phenomenon akin to war. Schenwar went on to major in English and creative writing at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania, where she tackled social-justice issues in a column in the student newspaper.

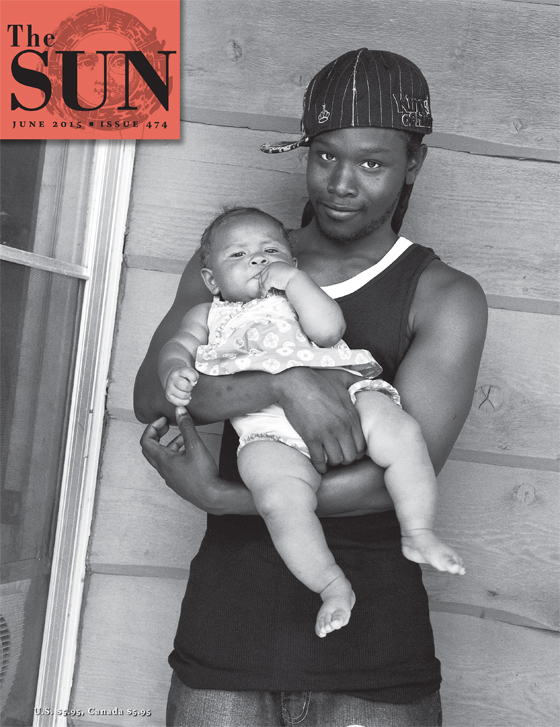

When Schenwar was twenty-two, her younger sister landed in juvenile detention for drug possession and, after her release, became a heroin addict. Schenwar’s sister went on to be incarcerated four times and gave birth to her daughter behind bars. Schenwar weaves this personal story into the reporting in her book, explaining that to write about prison without exploring the damage the system has done to her own family would have been disingenuous.

Since 2009 Schenwar has served as editor-in-chief of the nonprofit progressive news organization Truthout (truth-out.org). She has won awards for her writing on prisons, and her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Nation, The Guardian, Ms., and other publications. Prior to joining Truthout, she was a contributing editor at Punk Planet and publicity coordinator for Voices for Creative Nonviolence. She is chair of the board of the Media Consortium, a coalition of progressive news publications, and is on the board of advisors for Waging Nonviolence, a website that covers nonviolent activism around the world.

At about the time her sister was first arrested, Schenwar was working on a story about a hunger strike on death row in Texas. For her research she corresponded with several prisoners, and, after her piece had been published, the men kept writing to her. She became pen pals with one man, Steven Michael Woods Jr., who had been sentenced to death for murder, while his codefendant, who had actually pulled the trigger, had received a life sentence. Schenwar and Woods wrote back and forth about punk music and activism and their favorite places in Chicago, where Woods had spent a lot of time in his youth. Then Schenwar let the correspondence drop. “I stopped being able to figure out what to say,” she explains. “Here was a person who was about to die, and we were talking about everything but that looming fact. I had never felt so unable to do anything to help. I still feel very bad about it.”

Since then, she has corresponded with many other prisoners, some on a regular basis. While researching Locked Down, Locked Out, Schenwar came across a stack of letters from Woods and wondered whether he was still alive. She found out he had been executed the year before, despite the protests of Amnesty International and prominent social-justice activists like Noam Chomsky.

“The minute you connect with someone who is behind bars,” Schenwar says, “you realize that prisoners are human beings, whether you happen to like a particular individual or not.”

MAYA SCHENWAR

Frisch: Despite your opposition to the institution of prison, you reveal in Locked Down, Locked Out that at one point you found yourself wanting your own sister to be behind bars. Why?

Schenwar: That was definitely an emotional response that doesn’t line up with my politics. I, too, am susceptible to our culture’s notion that prison solves difficult problems like my sister’s drug addiction.

If you’re addicted to heroin in this country, you have to hide from the law. My sister was living on the street, sleeping in abandoned buildings, and overdosing regularly, but she avoided seeking care at hospitals, because she was afraid they would turn her over to the police.

My family and I were worried about her health and safety. So when she phoned me from the Cook County Jail, I was relieved: At least she wasn’t dead. At least she wouldn’t die of an overdose while she was locked up. Of course, this belief that prison could protect her was misguided, but it can be hard to give up.

Frisch: What led your sister to become an addict?

Schenwar: I think her initial time in juvenile detention was the turning point. Before that, she had been participating in school and had an active social life. Then she was arrested for drug possession. When I heard she was being sent to juvenile detention, I pictured a school building, only scruffier, but juvenile detention is a jail. You’re going to classes, but the main education you’re getting is in how to be a prisoner. A lot of kids graduate from there to prison.

Juvenile detention brands you a criminal at a young age, when your self-image is still so malleable. I could see the difference in my sister when she came out. She viewed herself as a bad kid after that. She started using heroin and became addicted. She served a couple of short sentences at the county jail, and after each one she immediately went back to getting high. At one point heroin was actually available inside the jail. I remember my dad went to pick her up from jail once, intending to take her straight home and put her into rehab the next day. When he got there, my sister had already left to score heroin.

Eventually she started shoplifting to get money for drugs. She was caught and sent to state prison. My parents and I thought maybe the experience would transform her somehow, but prison is traumatizing, and trauma doesn’t give birth to hope.

Frisch: There are 832 percent more women in prison today than there were in 1977. What accounts for this increase in female incarceration?

Schenwar: First you have to realize that there has been a 500 percent increase in incarceration overall since the early 1970s. But the increase is higher for women. One of the neglected stories about the war on drugs is that many women got arrested because their husbands or boyfriends or brothers were involved in the drug trade. I correspond with a woman in prison who was given a life sentence for drug conspiracy because of her husband’s drug-trafficking business. She watched her two young kids grow up from behind bars.

Frisch: Three-quarters of women in prison are domestic-violence survivors. Is there a connection between domestic violence and the increasing number of women in prison?

Schenwar: Many women, particularly black women, have been imprisoned for self-defense against a husband or boyfriend. In some instances the police arrive at the scene of a domestic-violence situation and arrest the victim. People have become more aware of the problem due to the case of Marissa Alexander, a black woman and mother of young children who was arrested in the midst of a fight with her estranged husband. He threatened to kill her, and she defended herself by firing a warning shot at the wall — not at him. That’s crucial. She didn’t harm anyone. But when the police arrived to investigate, Alexander was arrested. And this was in Florida, which has a stand-your-ground law saying that citizens do not have to back down from a perceived threat. But that law wasn’t applied in Alexander’s case.

She accepted a plea deal that got her released in January. She had already served three years in prison and is currently under house arrest for the next two years. She had been facing sixty years in prison for this supposed crime of firing a warning shot to defend herself and her children.

Frisch: Given that keeping families together has been shown to reduce crime, you might think that the criminal-justice system would treat mothers better.

Schenwar: Unfortunately neither the Federal Bureau of Prisons nor any state department of correction actually attempts to keep families together. For example, women who give birth in prison are immediately separated from their babies. Up to 10 percent of women enter prison pregnant. They are not given adequate nutrition, and they often do not have the option of an abortion, even though it is supposed to be legal everywhere in the U.S.

My sister was pregnant when she went to prison. One morning she was awakened at 4 AM, taken to the hospital, and induced. She had a difficult labor, and after the baby was born, my sister was immediately shackled to the bedposts. She was able to spend a little over a day with her daughter — though it was hard to hold the baby while chained to the bed.

My family was not allowed to be present. Nurses came in and out, but the only person constantly in the room with my sister during her long labor was a guard. She was allowed to make just one phone call afterward. Our mom put her on speakerphone. My sister was crying so much she could barely speak. She just kept repeating, “I love her, I love her, I love her.” Then someone took the phone away. My mom had to take care of the baby for the next few months while my sister sat in a cell, in the deepest agony she’d ever experienced. I kept thinking: This is how we punish someone for stealing perfume?

Frisch: How did you come to believe in prison abolition?

Schenwar: It was a combination of my sister’s experience, my reporting, and my relationships with people who are behind bars. The personal experience was crucial in moving me from the idea of reform to abolition, because I saw up close how prison deepened my sister’s addiction, crushed her self-esteem, narrowed her options for jobs and education, and diminished her hope for a good life. She was in a much worse situation each time she came out.

I run a progressive news website, and I can tell you that incarceration is one issue that progressives don’t agree on. Some want more incarceration for bank fraud or war crimes — as if that might make fraud or war go away. So I had to come to my own conclusions, rather than following a list of progressive talking points. I began speaking to people in prison about their insights. There are a lot of prison abolitionists inside prisons, although they don’t always call themselves that. They have good ideas about how to deal with problems without putting people in cells.

Most Americans are unaware that incarceration, as the default punishment for everything from drug possession to murder, is a fairly new phenomenon. Prisons, in their modern Western form, go back only about two hundred years. Of course, there were instances before that of people being locked up while awaiting some sort of physical punishment such as flogging or execution.

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries a group of people in England and the U.S. — many of them deeply religious, peace-loving Christians — said it was wrong to kill people for stealing a loaf of bread. They advocated for prisons as an enlightened alternative. The word penitentiary comes from penitence; it was originally conceived of as a place where isolation would lead to soul-searching and ultimately redemption. The experience wasn’t supposed to be pleasant; the earliest penitentiaries called for either near-constant solitary confinement or hard labor. But the idea was that criminals would come to see the light of God. Abbé Petigny, the warden of an early penitentiary in France, said that for a prisoner who isn’t Christian, prison is a “tomb,” but for a prisoner who’s Christian, it becomes a “cradle of blessed immortality.”

Not everyone thought this way, however, even in the eighteenth century. When novelist Charles Dickens visited Eastern State Penitentiary in Pennsylvania, he was horrified. He called the prison experience akin to being “buried alive.”

Frisch: Why do we have so many people in prison in the U.S.?

Schenwar: One reason is that we see prison as a solution to the problem of crime. Instead of preventing crime by allocating resources for healthcare, early-childhood education, food, housing, and other basic needs, we’re sending people to prison.

Another element is racism. The Thirteenth Amendment abolished involuntary servitude except for those who’ve been convicted of a crime. In this way a lot of African Americans continued to be enslaved. They were arrested for very small crimes, or often for nothing at all, and gathered up into the system. Especially in the South, there were and still are a number of prison farms on the grounds of old plantations. Angola Prison in Louisiana is one. The mostly black prisoners pick cotton, with the white overseers riding around on horses. It’s almost like a slavery reenactment. Then, after the Jim Crow laws mandating racial segregation in the South were struck down, prison and mass incarceration became a way to carry forward racial social control on a large scale.

Black people are 13 percent of the U.S. population but 40 percent of the U.S. prison population. A study found that black defendants in Illinois were nearly five times as likely to be sentenced to prison for minor drug offenses as white defendants who’d committed the same crime. And that doesn’t even take into account disproportionate arrest rates.

Michelle Alexander writes in The New Jim Crow about how mass incarceration perpetuates racial social control. Besides segregating black men from society, it creates a caste system in which the formerly incarcerated are second-class citizens. It’s difficult for them to get jobs. A study in New York found that 70 percent of parolees were unemployed. On most job applications you have to check a box if you have a felony conviction, and many employers will toss out the application when they see that box checked.

There are ban-the-box campaigns now in some states, but even without the box, a prison sentence leaves a hole in your résumé that’s tough to explain. This and other factors contribute to the likelihood that formerly incarcerated people will go back to jail.

Frisch: The cycle of going in and out of prison must be disheartening.

Schenwar: And disillusioning. The idea of freedom sounds good, but the circumstances you face upon release don’t always fit the mental image.

One man in prison wrote to me about someone he knew who’d recently been released. This man had spent twenty-one years in prison for bank robbery. He got out and couldn’t find a job, so he ended up robbing another bank. When he realized the cops were going to catch him, he shot himself in the head. In a newspaper article about the incident, the man’s son was quoted as saying that he’d been missing his dad for most of his life, and he couldn’t believe that, after prison, he had only four months to spend with him.

Frisch: In your book you write, “For many, going home resembles a different kind of incarceration.”

Schenwar: More and more parolees are being put on electronic monitors, so they’re basically kept under house arrest. Others are put on very strict supervision that they have to pay for themselves. Many are also mandated to undergo, and pay for, frequent and invasive drug tests. How many men and women who’ve just been released can afford all these fees? And the price for not paying them can be going back to prison.

Frisch: I’ve heard that people on parole and probation are not allowed to associate with others who’ve had felony convictions.

Schenwar: That’s a common stipulation. If people close to you have convictions in their past, it can make it difficult to maintain bonds of family and friendship. One of the strongest predictors of whether parolees will reoffend is whether they are able to rebuild those relationships.

A central theme of my book is how prison severs the ties between people. Some of the men I correspond with who have been in prison for decades have lost all contact with their loved ones. One man is from East LA, and he’s incarcerated at the northern tip of California. For his family to visit means a fourteen-hour drive and an overnight stay — all just for three hours of talking to him through plexiglass. He went into prison just after his daughter was born. She’s now fourteen. He gets two letters from her a year. His friends have abandoned him. His mother is really the only one who’s still in touch regularly. He is terrified of being released into a world where he has no close relationships left.

If we’re looking to rehabilitate people and prevent crimes, we should help nurture their relationships with family and friends. Prisoners who maintain ties with their families are less likely to return to prison. But the central fact of prison is isolation. It prohibits you from being a part of society.

Frisch: How does having an incarcerated parent affect a young person?

Schenwar: It’s tough on all family members, but it’s hardest for children. One in twenty-eight kids in the U.S. has a parent in prison. The number is one in nine for black children. If the incarcerated parent is a mother, the children are often removed from their homes. They might be placed with a family member they don’t know very well, or put into foster care. Being in foster care exponentially increases your odds of going to prison.

Aside from the psychological impact of the separation, there is the stigma of having a parent in prison. Kids with incarcerated parents can be ostracized not just by peers but also by teachers and neighbors. One child I interviewed said that, after his father went to prison, his friends’ parents wouldn’t let their kids play with him. The parents wouldn’t even sit next to his mother at basketball games. This boy was nine.

Research shows that strong community bonds promote public safety and reduce crime, but high rates of incarceration are tearing apart some poor communities of color, particularly in cities. Criminologists Todd Clear and Dina Rose, who study the ways that communities maintain safety, say the most crucial factors are “informal controls”: people knowing each other, looking out for their neighbors, caring for each other’s kids. Prison disrupts that.

Frisch: Doesn’t locking up violent offenders also make communities safer?

Schenwar: We’ve been conditioned to believe that the potential for violence exists only in certain people, and that if we can just lock all those people up, we’ll be fine. But violence isn’t limited to a few individuals. In fact, all of us have the capacity for violence.

We also have to keep in mind that the vast majority of people who are incarcerated aren’t in for murder, or child molestation, or any of the other “worst of the worst” offenses. Only about 7 percent have been convicted of killing someone. Are they, then, the truly dangerous people? Or are they individuals who, in desperate circumstances, did something horrifyingly violent for a wide range of often-overlapping reasons: money, anger, mental illness, fear, systemic racism, homophobia, addiction? Few of us know what we’re capable of under extreme duress. It’s a reassuring fallacy to think that we can just lock up the people we think of as “truly violent” and not address the roots of violence.

We know that mass incarceration doesn’t make us safe, because we have the world’s largest prison population and we still have violence in our society. Even in the 1970s, before the prison population quintupled, prominent social scientists were saying that prison doesn’t prevent violence. The government-sponsored National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals in 1973 recommended that no new prisons be built and that juvenile prisons be eliminated. It said prisons had “achieved only a shocking record of failure.” But policymakers did not follow the commission’s recommendations. Instead there was an overall shift toward punishment. In the eighties and nineties in particular, coinciding with the height of the war on drugs, there was an emphasis on “law and order” in politics: harsher sentencing, stricter penalties, more capital punishment. Politicians were eager to prove they were “tough on crime.” Of course, that didn’t mean funding measures that would actually reduce crime, such as education, mental-health care, or homes for the homeless. It meant incarcerating massive numbers of people. Mandatory-minimum sentences sometimes required a judge to send someone to prison for decades for a nonviolent crime. Prosecutors became more likely to ask for longer sentences or to pursue convictions that carried prison sentences. At the federal level parole was eliminated for anyone convicted after 1987.

Frisch: Violent crime has decreased considerably over the last couple of decades. Isn’t the increase in prison population at least partly responsible?

Schenwar: When the U.S. prison population first began to rise, it had a small limiting effect on crime. But a study that came out in February 2015 from the New York University School of Law’s Brennan Center for Justice shows that prison deserves zero percent of the credit for plummeting crime rates over the past thirteen years. In fact, the Brennan Center researchers warned that a high level of incarceration can increase future crime. The real reasons for the drop in crime rates aren’t fully understood. The Brennan Center study offers a “vast web” of economic and demographic shifts that account for most of it.

Frisch: So, if we aren’t clinging to mass incarceration, how do we build safe communities?

Schenwar: We have to have a broader definition of safety. Right now we equate safety with a lack of crime, but a crime can be anything from marijuana possession to murder. We need to look at what actually does harm to the community rather than just what’s against the law.

Certain crimes don’t cause significant harm — for example, drug possession. Meanwhile there are plenty of problems we don’t classify as crimes that do tremendous harm — for example, the immense economic injustices perpetuated by big banks. Once we start thinking in terms of harm, we can come to a more meaningful definition of safety. Protecting ourselves from economic injustice would mean reevaluating our economic system, which relies on keeping some people at the bottom while others accumulate massive amounts of wealth at the top. And what about prison: Doesn’t that do harm, especially to incarcerated individuals and their families?

Juvenile detention brands you a criminal at a young age, when your self-image is still so malleable. I could see the difference in my sister when she came out. She viewed herself as a bad kid after that. She started using heroin and became addicted.

Frisch: Are there more-humane prisons in other countries?

Schenwar: There’s an almost luxurious prison in Norway that features jogging trails, a music studio, private bathrooms, and a rock-climbing wall. Greenland’s Nuuk Correctional Institution allows prisoners to leave its confines on a regular basis to see family and go to work. These places are much better than the cages or “camps” into which we cram people here in the States. But I don’t think the solution to mass incarceration is to build better prisons.

First of all, Norway ranks 176th in the world for rate of incarceration, and the U.S. is first — so we’d be comparing apples to airplanes. Second, the U.S. can’t continue pouring money into institutions constructed on the principle of isolation. This isn’t to say we shouldn’t try to make life more bearable for the people currently behind bars. Reforms are necessary, such as humane visiting policies, better healthcare, and less expensive phone calls. Families pay outrageous rates for collect calls from prisoners. But reforming prisons won’t end violence, or build strong communities, or stop the disproportionate incarceration of people of color and the poor. Instead we’ve got to focus on drastically reducing the number of people behind bars.

Frisch: So how do we work toward a future in which we don’t put people in prison?

Schenwar: I’d be lying if I said I knew exactly how to get there. We need to devise those solutions together, as a society. But first we need to realize that the modern prison is not the only mode of justice. In South Africa, after apartheid was abolished, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was set up to address the massive human-rights violations that had occurred during the apartheid era. It practiced something akin to restorative justice, allowing victims to confront their victimizers and encouraging reparations. In Greenland there were no prisons until 1976. People who’d committed acts of violence were often taken in by northern fishermen and “reeducated.” In Samoa the perpetrator and the perpetrator’s family and community traditionally offer restitution and an expansive apology to the victim for acts of harm both large and small.

None of these practices is perfect — far from it. And they can’t all be replicated in every culture around the world. I’m not saying we should find one solution and implement it in all situations. We need to get creative in figuring out what we can do to prevent violence and heal the damage caused by it instead of just putting people in prison.

We could start by making sure everyone has housing, food, and healthcare, because when people’s needs are met, they are less likely to commit crimes. And we can get to know our neighbors and nurture healthy relationships with those around us, because in a safe society people look out for each other in both good times and bad.

Politicians were eager to prove they were “tough on crime.” Of course, that didn’t mean funding measures that would actually reduce crime, such as education, mental-health care, or homes for the homeless. It meant incarcerating massive numbers of people.

Frisch: What is restorative justice?

Schenwar: It involves bringing victims and their families together with perpetrators and their families. Both sides must be willing to meet without animosity, and the victims are never forced to confront the offenders if they don’t want to. Members of the community are also invited to observe and offer guidance. They all sit in a circle and talk about what happened, what led up to it, and how they were affected by it. Victims can say what would help them to move on. The perpetrators can also tell their side of the story. This doesn’t mean perpetrators aren’t held accountable. The goal is to reach a consensus, led by the victim, on how to make restitution. The process helps both sides see each other as human beings.

I interviewed people involved in one such program in Flathead County, Montana. In 2009 the county had the worst juvenile-recidivism rate in the state, so county officials decided to focus on prevention instead of on punishing youths. This majority-Republican county began to use restorative justice for almost all juvenile crimes. Almost five years later they had one of the lowest rates of recidivism in the state.

Frisch: Take us through a particular case you saw there.

Schenwar: In one situation a seventeen-year-old boy had stolen and destroyed the van of a commercial painter. Ordinarily the boy would have gone to juvenile detention for the crime. (My sister went to juvenile detention for far less.) But instead both the boy and the painter received counseling, and then they and their families were brought together in a “peace circle.” The painter talked about the effect the loss of the van had on his business and his employees, who couldn’t get their paychecks. The painter’s wife spoke about how the incident had left them with little money to buy Christmas gifts for their kids. Then the boy talked about how he’d grown up poor and was having a hard time in school and feeling desperate. When the boy expressed sincere remorse, everyone was crying. As restitution, on top of helping to pay for the damages, the youth had to write the painter and his wife monthly, detailing the progress he was making in school. They pledged that, if he stayed on track, they would give him a job, and they did.

Frisch: You’ve also said that, under some circumstances, restorative-justice programs are not effective. What circumstances are those?

Schenwar: In recent years some police departments have developed “restorative-justice” programs that give a different meaning to the practice. Sometimes officers will be present in the room. If the person who caused the harm has already gone through the violence of being arrested and jailed, police presence could prevent that person from opening up and being vulnerable. Feeling that you are in a safe space is crucial to the process.

Another situation is when the crime is sexual assault. Sometimes restorative justice can be used, but very often the victim does not want to be in a room with the perpetrator, even with counseling and after time has passed. We need to prioritize the victims’ needs in these situations. We can’t use the same model to deal with every offense. That’s what the prison system does, and we need to get away from that.

Frisch: From the victim’s perspective, is restorative justice preferable to the prison system?

Schenwar: I think so. Currently victims’ experiences are often ignored. Victims are not given financial support. They’re not given counseling. They’re not asked how they would like the perpetrator to be held accountable. Sometimes sending someone to jail feels like accountability, but often it doesn’t. Jail time doesn’t require offenders to make reparations, to apologize, or to take responsibility for their actions. If something has been stolen from the victim, none of the state’s money goes toward replacing it. Instead the focus is on punishing the person who has done wrong.

Frisch: You’ve written about a Chicago high school that uses a “Peace Room” to transform students’ responses to conflict. How does that work?

Schenwar: The program was set up through an organization called Umoja — Swahili for “unity” — and it operates in a couple of high schools in Chicago that once had high rates of punitive discipline. Police were often present at the schools, and arrests were made, mostly of black youths. There were high rates of suspension. Kids who get suspended or expelled are much more likely to be sent to prison later in life.

The Peace Room helps students deal with small conflicts before they escalate. Now, if there’s a fight in the hallway, the kids go to the Peace Room. In many cases students will voluntarily go there when trouble is brewing. The Peace Room has become a haven for kids who are having a problem with a teacher or another student or just within themselves. They can go to the Umoja staff to talk through their problems. Students can even attend a summer training program to become restorative-justice practitioners themselves. They then go to elementary schools and facilitate circles with the kids there.

Frisch: Let’s talk about bail reform. You cite a study showing that 87 percent of people arrested in New York City on nonfelony charges remained in jail while awaiting trial because they couldn’t pay their bail. Is the bail system fair?

Schenwar: The short answer is no. To me county jails are the most obvious example of how the so-called criminal-justice system does not provide justice. The majority of people in jail are legally innocent, because they haven’t had a trial yet, but they are incarcerated because they can’t afford to buy their way out. We’re effectively imprisoning people for being poor.

Frisch: What’s the alternative?

Schenwar: The best alternative is not to have monetary bail. Most people in county jails are not flight risks. Running away when you’re awaiting trial is a serious offense, and few defendants are willing to take that chance. Monetary bail is illegal in Washington, D.C., and that city hasn’t seen any resulting increase in crime.

Frisch: I’ve heard about people being jailed for failure to pay fines for misdemeanors and traffic violations, such as not wearing a seat belt or having a faulty taillight. The city of Ferguson, Missouri, which came to national attention after a police officer shot an unarmed teenager there in August 2014, issues an average of three arrest warrants per household in a single year and depends heavily on fines for its budget. What’s going on here?

Schenwar: Jailing people for not being able to pay traffic tickets and court fees creates a modern-day debtors’ prison. As I said earlier, people on parole can be sent back to prison for the inability to pay for their own supervision, drug tests, and electronic monitoring. They’re not imprisoned for committing a crime. They’re imprisoned because they can’t pay.

Frisch: Your interest in prisons began with an article about hunger strikes on death row in Texas. People in multiple prisons across the California system, including many in solitary confinement, were able to coordinate a huge hunger strike in 2013. What conditions were they protesting?

Schenwar: Solitary confinement is one of the most excruciating situations a person can be put in. The United Nations has declared the way solitary is currently used in U.S. prisons to be torture.

I correspond with a prisoner in Pelican Bay State Prison, where the California prisoner hunger strike started and was centered. His cell in solitary confinement was the size of a bathroom, and he was locked in there twenty-three hours a day. Solitary is often indefinite: people have no idea when they’re getting out, and they can be left in there for years without a hearing. The reasons people were ending up in solitary at Pelican Bay were murky. Often they had to do with being suspected of gang affiliation. While in solitary they were fed poor-quality food and not allowed to take classes or have opportunities for personal development.

Frisch: Did the hunger strike change any of that?

Schenwar: California legislators held hearings specifically about the practice of solitary confinement, and there have been a few changes at Pelican Bay. There are now terms by which prisoners can earn release from solitary. Prisoners in solitary can purchase better food and underwear, assuming that their families can pay for them. Still, there is clearly a long way to go. To me one of the major successes of the hunger strike was in mobilizing an enormous network. Family members and outside activists were able to work together with people who are living under the most severe confinement you could imagine. That in itself is a victory.

Frisch: What is a “supermax,” and how does it differ from solitary confinement?

Schenwar: A supermax is a prison that’s composed entirely, or almost entirely, of solitary-confinement units. The majority of states have either a supermax prison or a prison with a supermax wing or section. The phenomenon isn’t exclusive to the U.S., but, as with all things prison-related, it is used here on a much larger scale.

In my book I discuss Tamms, which was a supermax prison in Illinois. Prisoners there got to leave their tiny cells for just one hour a day, when they were placed in an outside cell for “recreation.” Tamms did not have a library. It didn’t have a dining hall. There was no yard, because in Tamms people didn’t leave their cells. They could make phone calls only if a close relative had died or was dying. Prison reformers succeeded in closing Tamms down in 2013. Unfortunately Illinois now has a couple of representatives who want to bring it back.

Frisch: How is it that we’ve let the situation become so bad?

Schenwar: Part of what allows us to perpetuate mass incarceration is that we label certain individuals as disposable. The attitude is that these people are criminals and therefore don’t deserve our attention. It’s easy to take a hard-line position when the people it affects are hidden from your sight, but the minute you get to know someone in prison, your consciousness starts to shift. You begin to understand that person’s humanity. You become able to imagine yourself in his or her position, as if you were talking to a friend in trouble. Empathy arises. Prison becomes real. You can imagine yourself enclosed by bars or going to the cafeteria to eat “nutraloaf.” The first sign for me that my consciousness was starting to shift was when I had dreams about being in prison. The feeling of not being able to get out was visceral. I still have those dreams. It’s a side effect of writing about this topic. Once you get that close to it, you can’t help but be transformed.