After my father died in 1973, my grandmother put newspaper over all the first-floor windows at night. Sometimes I wonder if she was more afraid of looking out than of someone looking in. She’d wait until after the six o’clock news to do the chore. Whenever she sensed my disapproval, she’d simply ignore it and say, “Mary, now, let me show you how I do it. Take that pin from my mouth and put it through the curtain and the newspaper. Careful. Now, don’t prick your thumb. See this?” She’d point to the Scotch tape around her thumb. “That’s so I don’t get poked.” I never got into a battle of wills with her; hers was, to say the least, stronger than mine.

My grandmother and I became roommates in my second year of life and remained so until I was twelve, when the oldest of my three sisters married and moved away. My grandmother’s room was at the end of a long hall, across from the attic closet and the stairs. Before I moved in with her, the closet doubled as my nursery. It housed my crib and a three-foot-high painting of Jesus with his crown of thorns and his bulging red heart exposed and his hands gently extended, palms up, like an invitation to come with him. Where? I wondered. (Only later did I learn how very few people actually got into heaven; most waited in purgatory forever.) Like a traveling art exhibit, that painting made the rounds in our Irish Catholic household. It started in the attic closet, then moved to my brother’s room, and then on to my sister’s, until she replaced it with a beat-up print of FDR that she’d bought for five dollars at an antique store. One night, probably scared by Jesus’ thorny crown, I had a nightmare and cried out in my sleep, “Save me! Save me!” Despite being hard of hearing, my grandmother arrived within seconds and scooped me up, and I was hers for the rest of my life.

Each night in her room, by the dim light of the street lamp in the alley, my grandmother sat on her chair with the dotted Swiss upholstery, put her feet up on a chest of drawers, and removed her junior-petite coffee-colored stockings. Sometimes I’d lie awake, watching her rub her calves, the blue veins slightly protruding like tunnels beneath her skin. Then she’d rest her feet in a tub of epsom salts and tell me how afraid she was of Judgment Day, or talk about her daughter who’d died: “There is nothing worse than losing a child.” Her top teeth sat in a Holiday Inn glass on the night table. Without her dentures, she sounded as if her tongue were swollen. She spoke proudly of how her daughter had been voted queen of her class in the seventh grade: “Only one person didn’t vote her in . . . and that’s because he was absent.” When she came to bed, I’d nuzzle up next to her backside. I loved to touch the soft skin of her arms and neck. I would encounter the same exact texture again in my twenties, as a waitress in a Chicago cafe, when I first felt the rind of brie cheese.

My grandmother was four feet eleven inches and not a breath over ninety pounds. She was sixty-eight when I was born, her hair already gone completely white after the death of her sixteen-year-old daughter from pernicious anemia in 1927. Her husband died in his late thirties that same year. She raised my father by working as a secretary at Bertman Electric Company and later at Saint Mel’s High School in Chicago. She never went by Grandmother, Nana, Grandma, or even her given name, Catherine. We all called her Chubby. She’d gotten the nickname from my father when he was a little boy; apparently, he’d heard kids on the playground calling someone Chubby and had liked the sound of the name so much he’d started addressing his mother by it.

After it snowed, my grandmother would walk in the tire tracks right smack in the middle of the street because she didn’t want to wait for the sidewalks to be shoveled, especially if she was heading to eight o’clock Mass. She often took me with her, pulling my seven-year-old hand, ignoring all cars: “They’ll stop, you’ll see. They’ll stop.” After I had outgrown my gray school-uniform sweaters, she wore them over her housedresses for years. Inside the wrist of her left sleeve, she hid several butterscotch candies; in her late eighties she decided to suck on hard candy all day rather than eat regular meals.

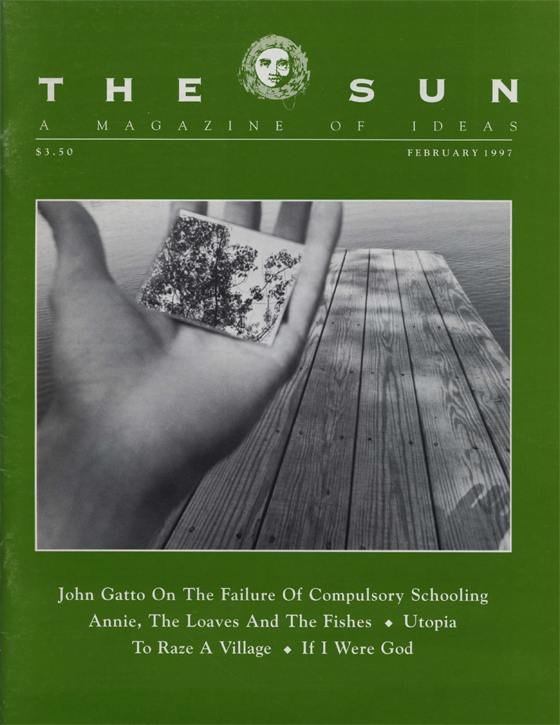

Once, when I was home from college on break, my grandmother came into the living room holding something in her palm. I thought it might be a dead butterfly, from the delicate way she was cradling it. As she crossed the pink-and-gray-speckled linoleum in the dining room, I could see tears in her eyes. Her deep red lipstick was smudged across her cheek. She bent down stiffly, as if wearing a neck brace, and showed me the jagged, brown-stained remnants of two bottom teeth; then she opened her mouth and pointed to where only sharp stumps remained. “All I ever wanted,” she said, “was to go out of this world in one piece.” I pulled her close to me, the way I had always done, even as a child of five or six, and patted the thin, jutting bones of her shoulder blades.

When I was four, my brother started nursery school, and I no longer had anyone to play with, so my grandmother took me to lunch every day at Holly’s Diner. I ordered the same combination daily: a grilled cheese sandwich with pickles, and a chocolate shake. She ordered nothing but cottage cheese, canned pear slices, and black coffee. To this day, those lunches define the concept of ritual for me.

In my grammar-school years, on rainy summer days — the kind that feel destined to be torturously uneventful — my grandmother would turn on the ten o’clock morning movie and we’d watch sophisticated Clifton Webb typing his column in the bathtub in Laura; or sad James Dunn returning drunk from a waitering job and singing, “Cockles and mussels, alive, alive-oh,” in A Tree Grows in Brooklyn; or sweet Anne Baxter fooling the hell out of Bette Davis in All about Eve.

But we didn’t enjoy only old movies. In 1969 we went to see Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Before the movie, a cicada flew into the lobby of the Liberty Theatre, and my grandmother rescued it in her white-gloved hands. She brought it delicately to the double doors and let it fly up into the Benton Harbor sky, into the clouds that looked like mountains over Main Street. As we went in to take our seats, she explained to me how cicadas shed their shells and cling to them after they pop out. While the credits rolled, she took her Vicks Vaporub from her purse, smeared some over her throat, then dug back into the jar for more, her index finger flailing like a grasshopper’s leg. Old people can do anything, I thought. As we walked to the exit, she said, “I didn’t hear a thing, but it looked like such a nice film. The cinematography was beautiful.” Her hearing got worse and worse until finally she taught herself to read lips. She would watch people’s faces and move her own lips as they spoke, whispering their words as if rehearsing them for her short-term memory; her long-term memory was reserved for stories about her daughter and her Irish mother, who played the piano by ear.

It’s been almost twenty-six years since my grandmother and I shared a room, and I can still hear the click of her garter belt as she rolls down her hose.

My grandmother was my confidante. I would often run up the back stairs to her room and tell her how my uncle had drunk three Old Fashioneds before dinner, or how my father had teased me about my weight. “Don’t you worry, my morning glory,” she’d say. “You have a beautiful mind.” (As an adult, I realized that, in a way, she was agreeing with my father by calling my mind, and not my size-fourteen body, “beautiful.”) When I was thirteen, I went on a diet. I remember bringing the bathroom scale into my grandmother’s room, where she kept a written record of my weight loss on the back of a yellow bank envelope. While I did my nightly leg lifts and sit-ups, she’d sit in her chair, her feet soaking in a bucket of epsom salts, and time me: “It’s been three minutes, Mary. Now do the other leg.” She had to hold her silver Timex up to her nose to see the second hand.

In her nineties, she took up reading. She would start a novel in the middle or read it backward, never really caring much about plot lines. She read thrillers about gun-toting drug smugglers in South America, a story about a nun who left the convent to marry a priest, and romances such as The Bride Came C. 0. D. She had to take what she could get because the library had only one shelf of large-print books. I first read The Catcher in the Rye in large print while I was home between jobs as a dog-food sales rep and an assembly-line worker at Zenith.

After my grandmother died from a stroke at age ninety-three, I found endless scraps of paper in her drawers: torn-off envelopes and corners of lined notebook paper containing her momentary worries, her records, her life. More than once she had written, “$160 cemetery lot.” So she wouldn’t forget the names of friends and relatives, she scribbled them on the back of a bank deposit slip, including the name of my best friend, Julie Couvelis, who would later die in a car accident at age twenty-eight. On several ripped pieces were repeated the joyful, sorrowful, and glorious mysteries of the rosary. To remind herself of where my brother worked, she neatly wrote out the initials NCR (National Cash Register). I came across the costs of Christmas gifts for my sisters and their husbands, and later their children, all neatly added in columns. I found, slipped into a yellow envelope, “Hawaii Five-O, Friday nights.” On a sheet folded neatly in quarters was the title of my first poem, “The Death of a Tree,” and underneath it the stanzas rewritten in shorthand.

It’s been almost twenty-six years since my grandmother and I shared a room, and I can still hear the click of her garter belt as she rolls down her hose. It is July and the windows are open in our second-floor room. There is a little bird’s nest wedged underneath the frame of the north window. My grandmother says they’re probably sparrows or house finches. I bring them crusts of bread on Saturdays while she is helping my mother with the laundry; I push a few crumbs through a small hole in the black screen, hoping the measly offerings will land in the nest. I can do this only when my grandmother is not in the room, for if she sees the crumbs on the sill she’ll warn me about ants, how we’ll get ants in our bed and in our clothes and in our hair if I keep doing this. Her right fist will be loaded with Kleenex and, in all her gesticulating, she will resemble a crazy woman surrendering.

And then I am grown, in my own room down the hall from her, creating a cardboard peace-sign mobile that I will hang from the ceiling. I am exchanging white light bulbs for yellow twenty-five-watt ones. In the corner is a drum set I have borrowed from a friend. Before long, I’ll be leaving for college in Arizona, far from this little southwest Michigan town known for its amusement park and pristine beaches. Still later, on summer break from college, I am sitting on her ribbed olive green bedspread, promising to take her on a ride in my Volkswagen bug, which I purchased for six hundred dollars with money I made working for the city, planting flowers in cemeteries and mowing the overgrown grass around the elms and maples in the park. She likes to have lunch up the road in Saugatuck, so we drive along the shore on Blue Star Highway, windows open, her wispy, salmon-colored scarf loosely tied babushka-style under her chin. “These are our days, peachie pie,” she says, “to be alive.”