That winter, after Betse and I discovered we were infertile, I became fascinated by pearls. My passion for them resembled an addiction, though I hesitate to call it that. There was a ritual aspect to it, a heady anticipation, an urgency I didn’t always understand.

Once, when we were driving in another city, I shouted for Betse to stop the car, then hopped out and told her that I would rejoin her in an hour. Like a junkie on his way to meet his connection, I didn’t tell her where I was going: to a jewelry store I’d just spotted.

Unbeknown to Betse, I often spent hours shopping for pearls. No visit to a new city was complete without a survey of the downtown jewelry stores. I took copious notes, comparing prices, strand lengths, pearl sizes, luminescence, nacre quality, and hues like “creamy pink” and “antique white.” When I walked into a shop, a newly married man in his thirties, the jeweler assumed I had romantic intentions. “Do you know how a pearl is cultured?” each one would inevitably ask. And I would listen, as if to a grandparent’s story, aged perfectly from the retelling: Under exact climatic conditions, a grain of sand (called a “nucleus”) is introduced into an oyster, irritating it and causing it to coat the foreign object with nacre. Usually the pearl that results is oddly misshapen, or “baroque,” as jewelers call them. Even the most desired pearl, a nearly perfect sphere with a smooth uninterrupted sheen, has tiny dents or tracks of roughness that hint at the natural process behind its origin. A cultured pearl is a carefully orchestrated accident, a product of both nature and human artistry.

As I became more and more obsessed with pearls, my secret visits to jewelry stores and conversations with jewelers resembled an affair. Pearls became an escape, a distraction, a dazzling hobby that transported me away from a home that suddenly seemed too empty. Shopping for pearls, I became, however momentarily, a different person: the dashing, romantic, pearl-buying lover that the jewelers assumed me to be.

As I walked down the hallway to the lab, discreetly tucked away on the seventh floor of an anonymous gray building, I felt as if everyone who saw me knew why I was there. When I arrived at the door, I knocked — too loud, it seemed — and a smiling woman answered. “I’m here to produce a specimen,” I announced, recalling the phrase the fertility specialist had used.

“Just a minute,” she said, going back into the lab, which was full of glass vials, microscopes, and mysterious dripping contraptions. I wondered about all the anonymous men who had been here before me.

Returning, the woman handed me a plastic container and a brown paper bag. “After you produce the specimen,” she said, “you can seal it in the container and place it in this bag.” Then she asked, “How many days has it been since your last ejaculation?”

The fertility specialist had told me no ejaculation of any kind for at least three days before the test. “Three,” I lied.

“Good,” she said, and handed me a key. “It’s Room 745.”

Room 745 looked like a storage closet that had been redecorated to appear vaguely romantic. Its concrete-block walls were painted pale blue with lavender trim. A print of Georgia O’Keeffe’s Music — Pink and Blue, 1919 hung on the wall: a mystical pastel breast, a vaginal cave. The furnishings consisted of a battered couch, a coffee table, and a bureau with drawers clearly labeled LINEN TOWELS, KLEENEX, PLASTIC GLOVES, and MAGAZINES.

With O’Keeffe’s pastel daydream blossoming overhead, I flipped through a copy of Penthouse: naked, airbrushed women’s bodies; coy, empty stares. I searched the dogeared pile for something different, but couldn’t find any pornography I liked. After a while, the silence and isolation of the chamber sank in. In spite of the strangers I’d encountered in the hall, in spite of the awkward triangle I found myself a part of — me, my partner, and whatever specialist or lab technician happened to be assisting us at the moment — I was able to produce a specimen.

Few processes in life are as vulnerable to superstition as the effort to conceive a child, especially as attempts drag on unsuccessfully. Notwithstanding the best explanations of doctors, fertility specialists, nurses, support-group members, lay experts, people who’d conquered it, and even old wives’ tales, my partner and I entertained all the stock superstitions: As busy professionals, we were “unable to relax.” As perfectionist worriers, we found it impossible to “forget that we were trying.” Although anathema to the young, professional couple, the element of surprise, everyone agreed, appeared to be a vital ingredient.

Alone, I found myself cataloging all my inadequacies as an American male: At thirty-three, I had never learned to drive a car. To make matters worse, I didn’t want to learn. Being a “sensitive man” in an atypical profession — family therapy — I did not fit the traditional mold. I was disappointed with the number and quality of my male friends. I didn’t own a house and was struggling to maintain a savings account. My body dissatisfied me: my biceps were too small, my chest too narrow. Only when I had corrected these myriad defects, I foolishly believed, would we conceive.

My most powerful superstition was that we were infertile because having a baby had never been a part of the life I had envisioned for myself. Though right now I wanted a child, for most of my life the thought of having one had never entered my imagination. While our doctor insisted on some unknown biological cause, I secretly wondered whether our infertility was due to a failure of wanting.

Behind all of this was a simple fact: I used to be gay. Actually, I would say that I still am gay, though some would dispute it. When I met Betse, I was taken by surprise that a part of me could passionately love a woman. But I was not “cured” of my gay identity. Once, at a conference for mental-health professionals, I heard another man describe himself as “a gay man who fell in love with a woman,” and I knew that someone else shared my particular minority status.

Before I’d met Betse, I’d expected to enjoy a certain kind of lifestyle: expensive urban condos, antique shopping, theater excursions, gourmet cooking, fantastic vacations, dinner parties with witty, overeducated guests. I wanted to question the status quo, the supplied ideas of who I should become, where I should belong. None of the typical bourgeois worries. Two incomes, no kids. Now, as Betse and I rode that infertility roller coaster of accelerating hope and crashing disappointment, I wondered whether our problem was ultimately rooted in my gay identity. Gay men can’t have children, I told myself. We can’t become fathers because we are radicals, queers, outsiders. It’s not part of the script. In the absence of any compelling scientific explanation (a situation faced by 10 percent of all infertile couples), I ruminated on the gay identity that I still held so dear, as if it were the source of our dilemma.

Chambers and Sons is a venerable Washington, D.C., jewelry store that caters to congressmen, professional athletes, and other capital elites. Leticia was their most successful seller. A petite woman with hair dyed an unnatural gold, she had once owned her own jewelry store, but it had fallen on hard times. She wore half-moon eyeglasses encrusted with tiny diamonds on the tip of her narrow nose, rings set with precious gems on every finger, long chains around her neck, and jangling bracelets on her wrists. She pulled out many strands of pearls to show me. “Of course, I’m not a beautiful young woman anymore,” she’d say, displaying them against her neck, “but you get the idea.”

One day, she confided, “You know, you remind me of my son. You’re just the age he was when he died.”

At first, I didn’t reply, afraid of what other intimacies this relative stranger, dear as my own mother, might disclose.

“He was an artist,” she continued, “a wonderfully gifted painter. He had a beautiful wife, and, just like you, he bought her pearls — a gorgeous, twenty-four-inch creamy pink strand. I helped him pick them out.” She shook her head. “He was my only child. But he didn’t value his precious life. He took it himself one evening, for no reason whatsoever. He just did it.”

“I’m very sorry,” I said, focusing on the glimmering pearls in my hand and trying to imagine them against Betse’s neck. Secretly, I rehearsed all the prejudices I found impossible to resist: What had this lovely woman done wrong? What had it been like for her artist son to have a mother so invested in beauty?

“They say mothers never recover from the loss of a child,” Leticia added, her eyes watering. “My husband had a nervous breakdown. He stays at home all day, doesn’t know what to do with himself. But I work here all the time . . . and it helps.”

She was putting away the pearls. “You think about what you want,” she said patiently. “Take your time. Your wife will have them for the rest of her life.”

For days afterward, I thought of Leticia and her husband, stranded in their separate orbits. I thought of her husband, shuffling around an empty house, unable to face what was left of his life. I thought of Leticia, putting in long hours, holding pearls to her neck and reminding gentlemen buyers, “Of course, I’m not young anymore . . . ,” as if apologizing for time’s passing.

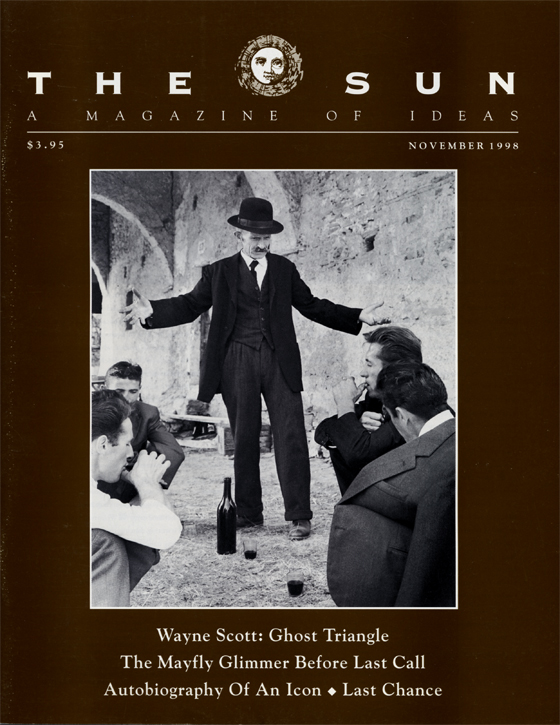

“Death ends a life,” we say in family therapy, “but it does not end a relationship.” Leticia and her husband were stranded in what family therapists call a “ghost triangle.” Their son, the third point of the triangle, was the ghost, an invisible but nevertheless real presence to them. Although no one could see or talk to him, he still affected their perceptions, hopes, and dreams.

Relationship triangles are relatively normal. They tend to evolve at times of heightened anxiety and uncertainty. Having been together for eight years, Betse and I were at an impasse. I was working, with limited success, to finish a novel. I had mastered my professional responsibilities, but the next career step, into a higher clinical position, was proving difficult. Betse had been looking for a new job for two years, but with no luck; openings at her level of her profession were scarce. Her parents had both had a series of illnesses that left them in uncertain health. Against this backdrop, getting pregnant gave us a fresh focus. It distracted us from the passing of time and the increasingly transparent signs of our age. I see now that we had been waiting for something to come along for a long time before that something became a baby. Conceiving a child took the spotlight off a more subtle existential dilemma.

The drama of infertility is an endless series of ghost triangles, except the triangulated spirit isn’t dead; it’s unborn. From the moment a couple first tries to get pregnant, that potential child becomes the third point of a relationship triangle. A lovely fantasy develops about it, like the nacre that coats the irritating grain of sand. A shift occurs in the life of the would-be parents. The imagined child helps them navigate an uncertain stage of their relationship.

Like Leticia and her husband, Betse and I were stranded in a ghost triangle, one certainly less tragic, but nevertheless painful. As our peers conceived, gave birth, and raised healthy children, we waited, hoped, took pregnancy tests, cataloged our shortcomings, collected old wives’ tales and superstitions, visited our doctor — and tried and tried again.

At the doctor’s instructions, Betse transformed her desire for a baby into methodical, daily rituals: She studied the process of conception in books, bought ovulation kits, took prenatal vitamins, visited an acupuncturist, and visualized herself pregnant. She counted and subtracted days, monitored the consistency of her vaginal mucus, waited for the tenderness in her breasts that signified the descent of a microscopic egg. In the back of her professional calendar, she kept a labyrinthine monthly chart on which she labeled the days of her cycles: Hollow dots represented premenstrual symptoms. Solid dots represented menstruation. Asterisks meant intercourse. Crosses meant waiting.

We had entered what psychologists who study infertility call the “immersion phase.” Our lives had become tethered to these conception rituals.

Betse resented not being able to share any of these chores with me. She couldn’t even talk about her struggle to pinpoint ovulation, because too much scientific talk interfered with my “job,” which was to have sex on schedule. If I knew that she was ovulating, I felt pressured and couldn’t perform. Sexual desire, a frequent casualty for infertile couples, was becoming tenuous for us.

Betse also had a luteal-phase defect — an obstacle to pregnancy, but not the sole cause of our infertility. To treat the condition, we embarked on a series of injections of a drug called Profasi, which lengthened her menstrual cycle from twenty-three to twenty-eight days, allowing the lining of her uterus to build up sufficiently to support a fertilized egg. The day of an injection, we would buy a bottle of our favorite merlot. Because she needed the anesthetic effect of alcohol, Betse would have two glasses, while I, needing to stay sharp, would have one. She’d hold an ice pack to her left or right buttock while I mixed the powdered Profasi with sterilized water and drew it into a syringe. I’d tap the needle until an air bubble rose to the top. Then I’d expel the air, along with a single tear of Profasi.

“Are you ready?” I’d say.

“Don’t ask,” she’d reply, not looking. “Just do it.”

I’d jab the inch-long needle into her upper hip.

Over the six months of injections, we never got used to them. We were embarrassed by the lengths to which we were going in order to conceive, ashamed that we could not simply “get over” our inability to have children. Weren’t there other ways to have a fulfilling life? Were we so dull and uncreative? There was an absence of grace. Somehow, these ritual injections made the depth of our narcissism too transparent. Couples who conceive easily possess the same narcissism, I am convinced; they’re just never compelled to confront it so nakedly.

One becomes an expectant parent long before actual conception. Betse and I obsessed about our infertility the way other couples talk endlessly about their children or dogs. Much to my horror, we became a cliché infertile couple. I was emotionless except for the occasional mood flare; she, because of prescribed hormones, was volatile, often inconsolable. Neither of us could believe the people we were becoming. Infertility was now a part of our identities. It defined my sense of self in the same way that “sensitive male” and “gay” and “writer” and “family therapist” did. Ironically, sometimes paradoxically, identities accrued, like strata of rock, each documenting the unique interaction of soil, weather, and time. Of self and circumstance.

I made lists of possible baby names: Julian, Sebastian, Rupert — names that were British-sounding, perhaps somewhat effete and artsy. Wilde, Whitman, Lawrence — the favorite authors of my young adulthood, all either gay men or men who questioned conventional heterosexuality. Listing potential names (all boys’ names, I should note) became another type of spree. I wasn’t simply choosing names; I was schematically designing an identity. And it was becoming plain: not only did I want a child who would be creative and artistic; secretly, I wanted a child who would be gay.

Baby names provided a kind of road map through my own inarticulate, thwarted desires. Confounded by multiple, contradictory identities, I was pulled in too many directions at once: gay and married; radical and conventional; novelist and therapist. I was haunted by the past selves I had compromised, neglected, or abandoned because they were incompatible with other cherished aspects of myself. Until now, I had avoided the grief of having put aside my gay identity. I was still a gay man, I believed, although not by outward appearances — certainly not by most gay men’s standards. I’m like a Jewish man who marries outside his faith, I rationalized. I’m gay in a cultural sense. But I was married. My wife and I were trying to have a baby. Like many parents, I wanted to look at a child and see him embody choices, still much loved and needed by me, that I had forsaken. Some expectant parents imagine a child who will attend the Ivy League school they couldn’t get into, or become a famous athlete in the sport they gave up. I wanted my child to be the gay man I was not.

My semen, tests indicated, was normal. Much to my surprise, gay semen was adequate to make a baby. Still, after six months of injections, the situation was becoming desperate. The doctor recommended that Betse undergo a surgical examination, including a laparoscopy, a hysteroscopy, and a pelvoscopy. A small camera would be inserted through her navel and directed down to her fallopian tubes. The doctor would then run a blue dye through the tubes to check for blockages, and examine Betse for any signs of endometriosis, a possible cause of infertility.

We debated the surgery option for weeks. Betse wanted the surgery. Even with the prospect of general anesthesia, incisions, recovery, and stitches, she considered the surgery less painful than the ambiguity of not knowing why we couldn’t conceive. She hated not having an explanation for so many failed attempts. While I felt the same way, I didn’t want someone cutting into her body. What had begun as a simple desire for a child had become a surgical assault on her, desire gone awry, a rape of sorts.

The night before her surgery, I broke down in tears. I hated my desire for a child, hated the narcissism behind it, hated the urgent need to understand what wasn’t working, hated the peer pressure rushing us along this path. Most of all, I hated that time was passing and we had no control over it. I was frightened by the prospect of growing old with only my partner’s company.

Meanwhile, carousing through jewelry stores, my behavior became campy. I squealed with pleasure like a little girl looking at Barbie dresses. I loved the feminine splendor of fancy jewelry, the vicarious pleasure of wearing things that glittered and shone. Acting this way helped me transcend the narrow person I had become, a man focused on the conventional desire to have a baby. But, in spite of these pretensions, I wore my plain gold wedding ring, and the jewelers treated me like a married man looking for a present for his wife. “What type of lifestyle does your wife have?” they would plainly ask, reminding me that I looked like someone’s husband, not a drag queen. “Does she dress professionally for work?”

When I opened my notebook to take down prices, business cards from jewelry stores in Washington, D.C., Chicago, San Francisco, and New York City spilled on the counter. Inside the notebook were pages and pages of notes, illustrated with drawings of matching earrings and fancy gold clasps. I had been searching for, admiring, and rejecting pearls for almost a year. The jewelers must have thought I was crazed.

On a trip to Jewelers’ Row in Chicago, I encountered a shop owner who forced the issue. I had been in his store twice that weekend to look at two beautiful strands. He took me aside and said, “Mr. Scott, what do we have to do to get your business?”

“What do you mean?”

“You obviously like these pearls,” he said, “and have been shopping for a long time. Tell us what you want to pay, and we’ll work with you.”

He was inviting me to bargain, giving me what he thought I wanted. “This is the price they gave me in Washington for an eighteen-inch strand,” I said, pointing to the back of a business card. “I want these two eighteen-inch strands strung together for the same price.”

The jeweler thought for a moment. “We can do that,” he said unexpectedly.

“Oh,” I said.

“We can have them strung and sent to you in D.C. within the week.”

I fumbled with my notebook.

“Mr. Scott?”

“Could I just take one more glance at the shop down the street? I saw something there —”

“It’s a one-time deal, Mr. Scott,” he said. “You need to decide now.” Up to that point, I had imagined that the purpose of looking at pearls was eventually to buy them for Betse. Now, with this tantalizing offer before me, I was oddly hesitant. If I made the purchase, I would no longer be searching, examining, questioning. The search would be over, but my urge to go to jewelry stores — those realms of taste and beauty that summoned my gay identity — would remain.

“It’s a deal,” I said.

“Congratulations, Mr. Scott,” the jeweler said, beaming. “You got yourself a gorgeous strand of pearls.” He and another salesman shook my hand. “Congratulations,” they said, as if I had announced my engagement, or that my wife and I were pregnant.

After Betse’s surgery, the fertility specialist, still wearing her green surgical garb, invited me into a consultation room. She had to pull down her mask to talk. The operation, she said, was a success. Betse was recovering nicely. The examination had uncovered no functional abnormalities. It had detected a trace of endometriosis on Betse’s left ovary, but nothing that would explain our difficulty conceiving.

The doctor showed me several color photographs of Betse’s insides. Her ovary was a pale gray bulb hanging against pink tissue. Its smooth surface glowed white in the light from the camera. The doctor took a pen and pointed to some vague marks on the ovary’s side. “This is the endometriosis,” she noted. “An extremely mild case.”

I remember thinking that Betse’s ovaries were beautiful — like pearls, with their opalescent glow, the slight, rough tracks, necessary flaws interrupting otherwise-perfect globes. What were we doing? How had we been fooled into thinking there was something wrong, just because we couldn’t get pregnant quick enough to suit the urgency of our wants? As the doctor talked and my partner lay asleep in the recovery room, I thought, We’re done. No more tests. No more injections.

Over the next week, the doctor, whose job it was to facilitate conception, encouraged us to consider fertility drugs, an aggressive, high-risk treatment that had nearly bankrupted other couples we’d met. Still shellshocked from this last battle in the war against infertility, we said no. We were tired. We were taking a break.

That Christmas, when I gave Betse the pearls, she cried. Under the glittering lights of the tree, I was finally able to reveal my secret: the ardent search, the shopping excursions that, like a love affair, had taken me away from her and into places where I’d been both a fussy gay consumer and a married man passionately in love. Both identities were true. I did not need to sacrifice one for the other. I was grateful for my many-layered sense of self, for it allowed me so many ways to express my wanting, which was never so simple as having a child, or having sex with another man, or purchasing pearls for the woman I adored.

As I talked, Betse experimented with the strand of pearls: wearing it loose, knotting it, twisting it, doubling it. Through the story of the pearls, we were discussing all it had meant to search and want. As we talked about what it meant to be infertile, the ghost of our unconceived child wavered in the background. Then we drew closer, and for a moment there were just the two of us, alone together, under the tree.