Yesterday, I saw so much unhappiness in people’s eyes, all of us rushing somewhere. Construction noise and dust filled the air; we could have been hurrying down some boulevard in hell. And I was reminded that this is hell unless I extend compassion to those around me. If my heart isn’t open, I’m just another tourist here, collecting memories, looking for the perfect souvenir.

Norma returns. Loneliness packs his bags. Loneliness just wants me to know he liked it better when she was gone. At least I paid some attention to him then. Didn’t I see he wasn’t really dangerous?

Since coming back from New York, Norma has been a little irritable and withdrawn. I need to remember she’s been living in a starkly different world. Like those workers in hardhats digging through the rubble at Ground Zero, she’s been digging through the rubble of broken lives, listening all day to the stories of those who lost their jobs or their homes in the September 11 attack. I’m glad she went because I know what a good listener she is. She’s like a piano teacher who asks a student to play a piece she’s heard a thousand times before. She closes her eyes. She listens to every note.

I haven’t set foot inside a synagogue in years. Yet, like many Jews, I wrestle with my God. I take personally the suffering I see around me, and don’t understand how a merciful God could allow it. As if God’s mercy were something I could understand. This God who destroyed the world in a flood to punish humanity for being . . . human. This God who slaughtered Egypt’s first-born to teach the Pharaoh a lesson. This Mother of All Terrorists who lashes out with no warning. None of the people Norma spoke with got any warning. Now they’re just barely getting by. Even the rich, Norma says, show up for their handouts. Even the rich didn’t get a warning.

Graham Greene: “You can’t conceive, no one could, the appalling strangeness of the mercy of God.”

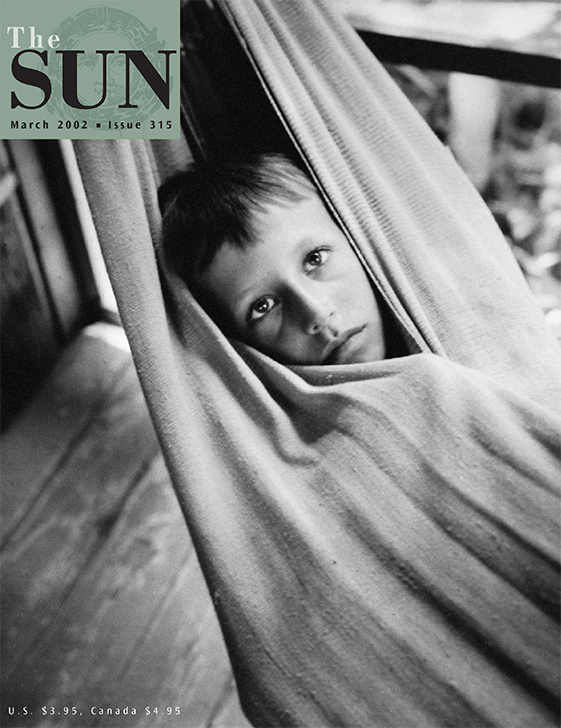

Let’s send sad-eyed soldiers to Afghanistan, spiritual warriors who can win the people’s hearts with the depth of their compassion.

True, I don’t know much about being a soldier. I don’t know what it’s like to run from enemy fire, bullets whizzing past my ear, a thousand bees humming my name. I don’t know what it’s like to kill a man, then watch his ghost rise up and step toward me. No, I don’t know much about being a soldier. But then, neither does George W. Bush.

Once again, we’re down on our knees. And our prayers are the wrong prayers. And the wrong gods are listening.

Perhaps I’ll wait to judge others until I’ve risked my life to save a thousand-year-old tree; until I tear up the check I just wrote to a favorite charity and write a new one, adding an extra zero at the end; until I slip a couple of bucks to the homeless man outside Starbucks instead of walking in and ordering a cappuccino. Make that skim milk, please.

How many ways do I love the morning? The morning doesn’t ask me to count them. The morning doesn’t ask to be flattered, or insist on my undying devotion, or ask me to choose between morning and night. A child is being born this morning; an old man is dying; a terrorist is connecting the wires on a homemade bomb. The morning isn’t insulted. The morning isn’t proud.

Is it possible to live each day knowing that everything will go wrong — that everything is falling apart right now — yet remembering, too, that this in no way denies the living truth, the love at the heart of existence?

I don’t need to begin the day in front of the mirror, wondering how others see me. Let me start on my knees instead. Let me ask not to be a better writer, but a better man; not to be more admired, but to admire the beauty all around me, the splendor of the mundane. Let me remember that the ocean of life in which I’m swimming is also the ocean of love. Let me remember that blessed is the man who drowns in love, and blessed is the man afraid of drowning, as he paces the deck of the mighty ship he hopes will save him: ship of money, ship of words — what does it matter? He stands by the rail and stares into the dark water.

The Sufis say that anything you can lose in a shipwreck isn’t yours.

Saint Valentine was a third-century Christian martyr. Eighteen hundred years ago, he gave his life for Jesus. Tonight, I’ll invoke his saintly memory to tell Norma how much I love her. Then I’ll hand her the pair of earrings I bought for her last week. Deep red garnets set in silver. Blood of the lamb. We weren’t supposed to exchange gifts, but, hell, life is short.