I was never a big fan of formal education, so when my son decided he had better things to do than attend his high-school classes, I supported him. He wanted to become a filmmaker, and I wrote notes to excuse him from school so that he could shoot film and go to the movies.

He attended only enough classes to graduate, and I wrote many excuse notes, always to a woman named Ms. Finn. I pictured Ms. Finn as half librarian, half prison warden, frowning at my notes, scrutinizing every word, looking for some hole in the iron-clad excuses I had concocted. This battle of wits with Ms. Finn inspired me to write even better excuses, brimming with legitimacy. I raised the excuse note to an art form.

Then one day my son told me Ms. Finn was not actually reading these notes. In fact, she was barely looking at them. Ms. Finn, it turned out, was a long-haired free spirit not much older than my son.

The image of Ms. Finn as a carefree hippie sapped the intrigue from my excuse writing — until I came up with a new angle: I would write excuse notes so outrageous that even she couldn’t ignore them. With each failed attempt, I turned up the heat, to the point where my notes lost touch with reality:

“Dear Ms. Finn, Michael has yellow fever.”

“Michael has grown suspicious of his pets.”

“Michael just learned that he has an evil twin.”

But my personal favorite was the simplest. On a large piece of paper, I wrote just three words: “No clean clothes.”

Marilyn Kalish

Great Barrington, Massachusetts

Twelve years ago, while enrolled in a graduate writing program, I met two significant people in my life: the woman who would become my wife; and Barb, a dear friend and the best critic of my writing I ever had.

It made no sense for Barb and me to become friends. We were opposites in every way. She dabbled in drugs, had once worked as a phone-sex operator, and slept with men of questionable character. But I always knew I could count on Barb to tell me the hard truth: about my stories, about my life, about my relationships.

Shortly after I began dating my future wife, Barb warned me that if I stayed with this woman, everything I wanted would slip through my fingers. She felt as though she was watching me die, she said.

“Pick me as your friend, or her as your lover,” Barb told me, “because I won’t stay around to watch you wither away in conformity.”

Two years later, I was engaged and living far from the town where I’d attended that writing program. An old acquaintance called with the news that Barb had died from AIDS. She had told almost no one she was sick, keeping up appearances even as she prepared to die. Though we’d had our falling-out, I was disappointed that she hadn’t called me.

When people asked why I didn’t go to Barb’s funeral, I told them my fiancée wouldn’t let me. When, several weeks after Barb’s death, I gave up on serious writing, I blamed the sound of Barb’s angry criticisms in my head. When I abandoned university teaching — the one remaining facet of the literary life I’d always wanted — I told myself it was to focus on my duties as husband and father.

As my marriage unraveled a few years later, I claimed that leaving the university hadn’t been my decision at all, that I had been bullied into taking that path. None of it, I said, not a single bad decision in the preceding eight years, had been my fault.

A year ago, I resumed writing after a ten-year hiatus. I’m taking responsibility for how my life has turned out and peeling back the layers of excuses that have prevented me from living. I’d forgotten how hard confronting life without excuses could be.

Recently, I stumbled upon one of Barb’s notes on a story of mine. “People are guided by will and emotion,” she wrote. Though we might blame others for the things we do, she said, our own minds and hearts govern our actions. If Barb were here, I’d tell her that she was right.

Name Withheld

I had a physically and emotionally abusive childhood, and as a young adult I came to the agonizing decision that it would be best if I didn’t have children.

Several years later, my brother and his wife asked if I would be the godmother of their first child and take the role of “hands-on aunt.” I had to say no. Even to be secondarily responsible for a child seemed beyond my capabilities.

My mother, my husband, and my closest friend all accepted my explanation for why I was not up to this task. They nodded their heads sympathetically and said, “No wonder.” But I don’t buy my own excuse. I despise myself for failing my brother, his wife, and their child. I have lived for ten years with the shame and regret.

Name Withheld

Alex was a charismatic teenager, and the most entrepreneurial student I have taught in my fifteen-year career. He started his own grocery-delivery business and frequently came to my class bleary-eyed because he’d been up all night itemizing produce, cereals, and cleaning products.

“Alex,” I’d say, “where’s your Hamlet essay?”

He would smile and shrug his shoulders. “Fisch, what can I say?”

I’d let him off every time.

Alex had the lead in the school play. On opening night, while the other drama students celebrated with their families, I noticed him standing alone, leaning against the wall and trying to appear aloof.

“Are your folks coming tomorrow night?” I asked.

“Nah, my dad doesn’t really care what I do. It’s OK. I don’t do it for him. Acting is for me.”

On Monday, Alex came to class empty-handed yet again.

“What’s your excuse this time?” I asked.

“I’ll tell you after class, Fisch.”

When the other students were gone, it all came out: Alex’s father beat him. Fed up, Alex had moved out months ago. He’d lived in his car, until it got too cold. Since then, he’d been living in the school building, which was often unlocked due to renovations. He studied by candlelight in the library and showered in the locker room before the buses arrived. He raided the dumpster behind the cafeteria for dinner.

To my knowledge, I am the only one who knew Alex’s secret, and I guarded it until well after his graduation.

Three years later, Alex wrote me a letter from college. He was thriving and had started a string of new enterprises to pay for his education. He had decided to change his name legally, to finalize his separation from his father.

To this day, I occasionally look at a bedraggled, bleary-eyed kid in my English class and wonder what happened to him the night before. What excuse will I hear today? Will it disgust me? Amuse me? Break my heart?

Pam Fischer

Indianapolis, Indiana

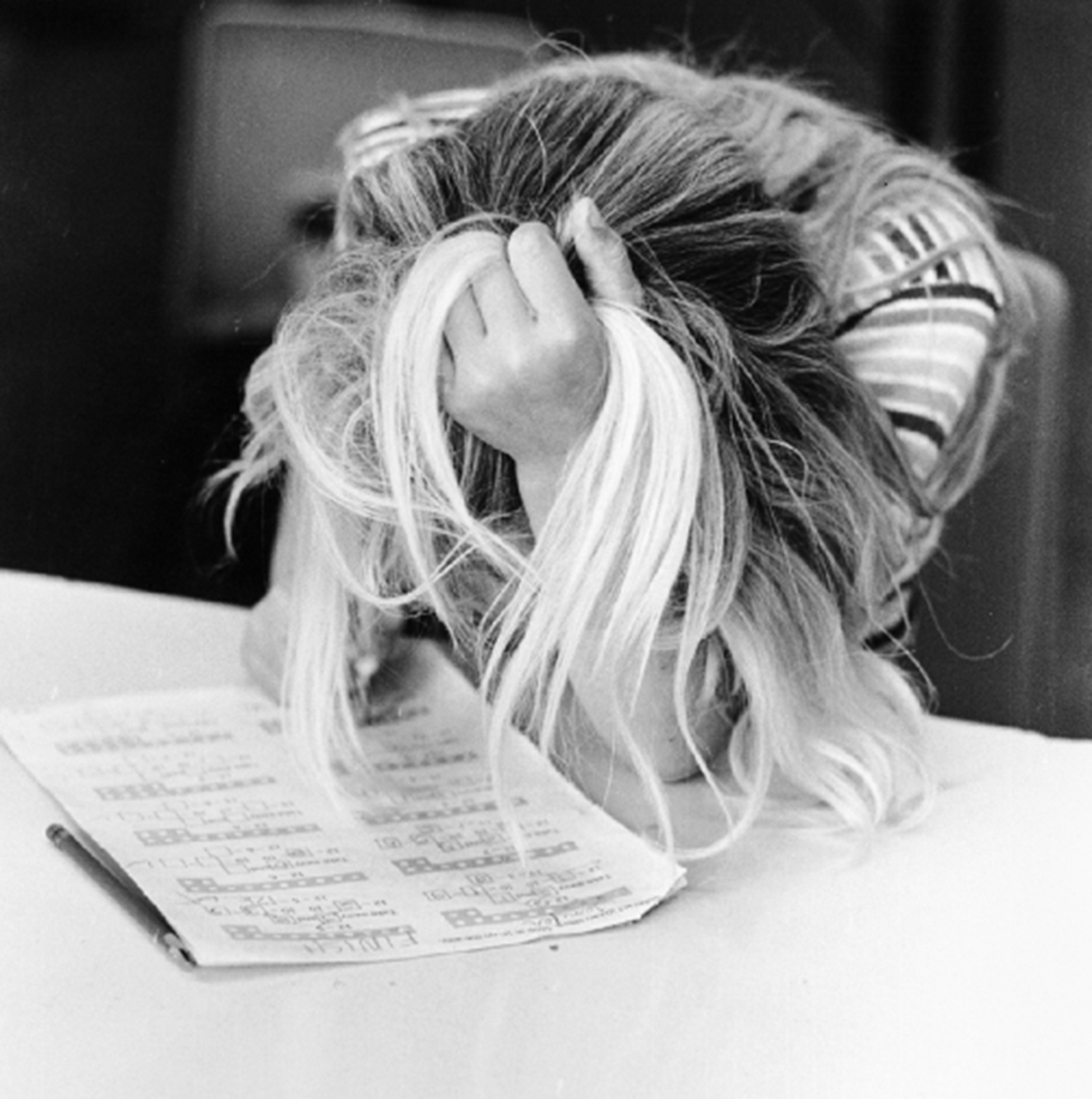

I can’t write today. It’s too hot. The topic is boring. I’m too tired. I’ll get a fresh start in the morning. I need a snack first. Let me sharpen my pencil. My computer has a virus. I have a virus. I have to call my boss. I have to walk the dog. I have to check my e-mail. I have to do my taxes. I have to wash my hair. My dog got sick. My kid got sick. The news is on. The West Wing is on. Letterman is on. I need to work out. The phone keeps ringing. Someone’s at the door. I have to rotate my tires. Something came up. It’s time for lunch. It’s time for dinner. I have a headache. I sprained my finger. I have carpal tunnel. I forgot. I overslept. I didn’t know it was due today. I had to work late. I left it on the bus. I left it in my other notebook. It got lost in the mail. My dog died. My muse left. My wife left. The Prozac wore off. I ran out of gas. I ran out of excuses.

John Unger Zussman

Kapalua, Hawaii

I spent the better part of two failed marriages working part time and scrambling to obtain my teaching credential. Once I was accredited to teach secondary biology, I decided that I didn’t care for that age group. I would get my elementary credential, too. My mother, a veteran teacher, was overjoyed when I finished the program. Meanwhile, I was worried about how confining and relentless the grade-school day would be.

I began working as a substitute. Most days I was overwhelmed by the sheer effort of winning over a class and holding out till the end of the day. I began to realize that teaching would consume hours of my personal time, and that the pay for a beginning teacher was significantly less than my previous salary. I found fault with the administrators and decided it would be difficult to work with them.

Invariably, there were a couple of impossible students in every classroom. After the principal caught one of my seventh-graders climbing out a window, I ruled out junior high. Then I spent a frustrating morning with a crayon-chewing, fit-throwing kindergartner who crumpled on the carpet whenever I asked him to do anything. I was not cut out for that grade level, either. I ruled out special education after a student told me he was thinking of ways to kill me. When spring arrived — time for job applications to be submitted — I limited my chances by applying only to schools that were within a twenty-minute drive of my home.

At some point during that summer, I accepted what I should have known from the first day: I did not want to teach. I had been making excuses for ten years.

Name Withheld

I was concerned about my daughter Sarah. She wasn’t herself and hadn’t been for weeks. Whereas ordinarily we talked at least once, and sometimes two or three times a day, now I got her answering machine. Rarely did I get a call back, and if I did, it was usually her husband, Nick, calling to say that Sarah was in the shower or lying down or not feeling well or just plain too busy to talk. Sorry, he didn’t have time to talk either. Sure, he’d give her the message.

If Sarah did happen to answer the phone, she always had an excuse at the ready: “Sorry, we’re busy Saturday.” “No, I don’t think I can make lunch today. I’m not feeling well.” “Dinner? Maybe another time, Mom. I promised Nick steak and a baked potato tonight.”

One day I decided just to show up on her doorstep and insist that she go to lunch with me. At the restaurant, I would ask her point-blank why she was avoiding me and if she wanted me to stop calling her — even though the thought of it brought tears to my eyes.

As I parked in her driveway, I noticed a bookcase that used to be in her living room lying in pieces on the carport with books strewn about. I wondered what excuse she would give when I asked her about it. Walking to the porch, I saw that all the blinds were drawn. Odd. Sarah hated to keep the house closed up. When she lived at home, she used to go dancing through the house, opening all the windows, even when it was raining, laughing at my objections.

I knocked on the door and waited. No one answered. I tried the handle. Locked. As I turned to walk away, something caught my eye: one of the blinds swaying ever so slightly. I knocked again, and I heard the sound of not one or two, but three locks being unlatched.

“Mom!” Sarah said. “What are you doing here? Why didn’t you call first?” She stepped out and pulled the door shut behind her.

“Well?” I said. “Aren’t you going to let me in?”

Before she could make an excuse for why she couldn’t, I pushed by her. It had finally dawned on me that something was going on, but I wasn’t prepared for what I saw: dishes overflowing in the kitchen sink; leftover food on the counters; clothes and magazines piled on the floor; empty beer bottles lined up on the coffee table in front of the TV; and a large hole in the living-room wall where the bookcase used to be.

“What’s going on here, Sarah?” I asked quietly.

She hung her head to hide her face and tugged her robe across her chest. I pulled her to me and held her tight. “Why didn’t you tell me?” I asked. “Why?”

“He didn’t mean it, Mom. It’s just that he’s been working extra hours, and when he comes home he’s exhausted, and . . . It’s my fault, Mom. Somehow I make him mad. I don’t do anything right, and you can’t blame him. He’s just trying to make me a better wife.”

Name Withheld

I have been secretly in love with a married woman for the past year and a half. Although my wife knows of my attraction, she doesn’t know its full extent. I make excuses to cross a room so I’ll bump into this woman. I do projects with her husband just to see her. I arrange our child’s car-pool schedule to coincide with hers. I dream up reasons, however lame, to call her.

Realizing that things were getting out of hand, I went five months without contact. Then, two weeks ago, I spoke to her. Since then I haven’t slept through the night. I wake up either thinking of the last time I saw her, or wondering when I will see her again.

I feel like a leaf floating and swirling in a breeze. I know that, to be true to myself, my family, and my friends, I have to avoid all contact with her. But part of me just wants to swirl.

Name Withheld

I have bad work habits, so I learned early on to make excuses. But by the time I got to college, all the lying was wearing me down.

One day I decided I couldn’t do it anymore. I went up to my political-science professor after class and told him flatly that I didn’t have my report.

“What happened?” he asked.

“Nothing happened,” I answered. “I just didn’t do it.”

“Are you sick?” he asked. “Is there an emergency in your family?”

I was stunned. Here I was, ready to tell the truth, and he was making excuses for me.

I admitted (falsely) that, yes, there had been a death in the family. The professor seemed relieved. He offered his condolences and gave me a week’s extension on the paper.

Name Withheld

I eat because I had a bad day. I eat because I had a good day. I eat because I am not going to start my diet until the first of the year. I eat because I have already blown my diet anyway. I eat because everybody else is eating, and I don’t want to appear rude. I eat because I’m home alone and nobody will know that I am eating.

I weigh three hundred pounds because I eat too much. I eat too much because I weigh three hundred pounds.

Name Withheld

I’ve spent the bulk of my working life in various service jobs: waiter, landscaper, housecleaner, nanny. I have almost gone to graduate school twice, once for law and once for clinical psychology. Both times I was elated at having discovered my purpose in life. Finally I would have an answer for the question “So, what do you do?”

But each time the euphoria wore off, I began to think about what it would be like to work in the mental-health field under managed care; or as a lawyer surrounded by, well, lawyers. More importantly, I began to ask myself how much my choice to go to graduate school was about becoming a person who would inspire respect and admiration in others — especially my father. Graduate school was more about seeking approval and acceptance than it was about following my heart.

I decided to focus on things that would satisfy me deeply. I resolved to write more, climb Mount Rainier, learn to scuba dive, pay off my debts, read the classics, do volunteer work, exercise, practice mindfulness, and generally live a rich and fulfilling life.

I’ve done many of these things, but sometimes, when I come home exhausted after eight hours of changing diapers and picking up toys, I wonder if my commitment to living an authentic life is just another excuse to make me feel better about doing a job I don’t want to do.

Arissa H. Rench

Seattle, Washington

While I was raising my children on my own, I went a long time without a sex life. Aside from not having the energy, I felt invisible as a woman. I held back my desires and concentrated on the kids, money, finishing my degree, and going to work in a demanding profession.

After the kids were grown, I began to feel more sensuously alive than ever before, but I was tying my sex life to the idea of finding a life partner, and there weren’t any prime candidates on the horizon. It seemed almost cruel — this explosion of sexual energy coinciding with a lack of available men. I wondered whether I should try bisexuality, just to double my chances.

Instead I began looking for lovers rather than potential partners. If a soul mate came along, wonderful, but in the meantime I wanted to celebrate passion and sensuality.

I started an e-mail affair with a married man. He sent me playfully explicit messages that made me laugh. I struggled with my conscience and told myself the affair would never cross over into real life. It was a virtual affair, a fantasy. Meanwhile I was going out of my mind with physical frustration.

I decided to compromise. I told myself that this man’s life was his own business. I knew that I’d be contributing to the decline of his marriage, and knew that I’d never trust him as my own life partner. But could it be any worse than all these years of burying a part of myself?

Today the real affair began.

Name Withheld

When I taught high-school English for the Peace Corps in Cameroon, young men would disappear for two or three weeks and, upon reappearing, inform me they had been helping their families in the fields. A cocky and defensive twenty-two-year-old, I told these young men, in my best teacher voice, “Though I understand that you need to help your family with the harvest, I’m afraid your absence from class will only hurt you when you take your national exams.”

Now, from the distance of fourteen years, I cringe at my response. But I was young, I tell myself, and trying to establish my authority in the classroom.

When I was a teaching assistant in graduate school, a quiet young woman came to my office one day to dispute her classroom-participation grade. She explained that she had always been shy. I told her that I understood, but that the course was rhetoric, and in order to argue effectively she must learn to write and speak. The mood became tense, and I thought I saw tears forming in her eyes. She left before we could arrive at an understanding.

A year or so later, I read of that student’s suicide on the front page of the student newspaper. The article spoke of an eating disorder, roommate issues, and troubles with school. I thought about how I might have handled that encounter differently.

A few years ago, I was teaching an honors composition course — my first job out of graduate school. The course was filled with bright and talkative students, almost every one of whom, it seemed, had a grandparent who died that semester. When a young man who was doing poorly in the class arrived at my office door to announce his grandfather’s death, I offered my condolences but asked him to please return to class the following week with an obituary.

The student appeared in class the next week, obituary in hand. It said his grandfather had been a decorated war hero and a pillar of his small New Jersey community. I thanked my student for having let me read about his grandfather and apologized for having doubted him.

I’ve never again questioned an excuse from one of my students.

Mary Beth Simmons

Villanova, Pennsylvania

When my father got home from work, he’d pop open a can of beer and say of my mother’s cooking, “This is a poor excuse for a meal.” If he saw an old dog hobbling down the street, he’d remark, “That’s a poor excuse for a dog.” If a woman was not attractive to him, he would say, “There goes a poor excuse for a female.”

When he got fired, he said his boss was a poor excuse for a businessman. When my mom left him, he said she was a poor excuse for a wife. When he threw me out of the house, he said I was a poor excuse for a daughter. When he was dying of lung cancer and still smoking two packs of cigarettes a day, he said his surgeon was a poor excuse for a doctor.

Two weeks before my father died, I was trying to help him to the bathroom. He could hardly walk without falling. He said, “You are a poor excuse for a . . . ah, forget it.”

Struggling to hold him up by his belt, I said, “Dad, I am not a poor excuse for a nurse. I am the only nurse you’ve got.”

He sat down on the toilet and mumbled, “I know, I know, I know.”

Carole U.

Franklin, Tennessee

When I heard my friend had cancer of the colon, I didn’t write to her because I didn’t know what to say. I didn’t call because I thought she’d prefer to be left alone. I didn’t visit because we weren’t that close. I didn’t send soup because I’m not much of a cook.

When I saw her on the street, I didn’t ask how she was, in case the news wasn’t good. I didn’t tell her how beautiful she looked with her close-cropped hair.

I’ll probably never tell her. It would be too awkward.

A.

Port Townsend, Washington

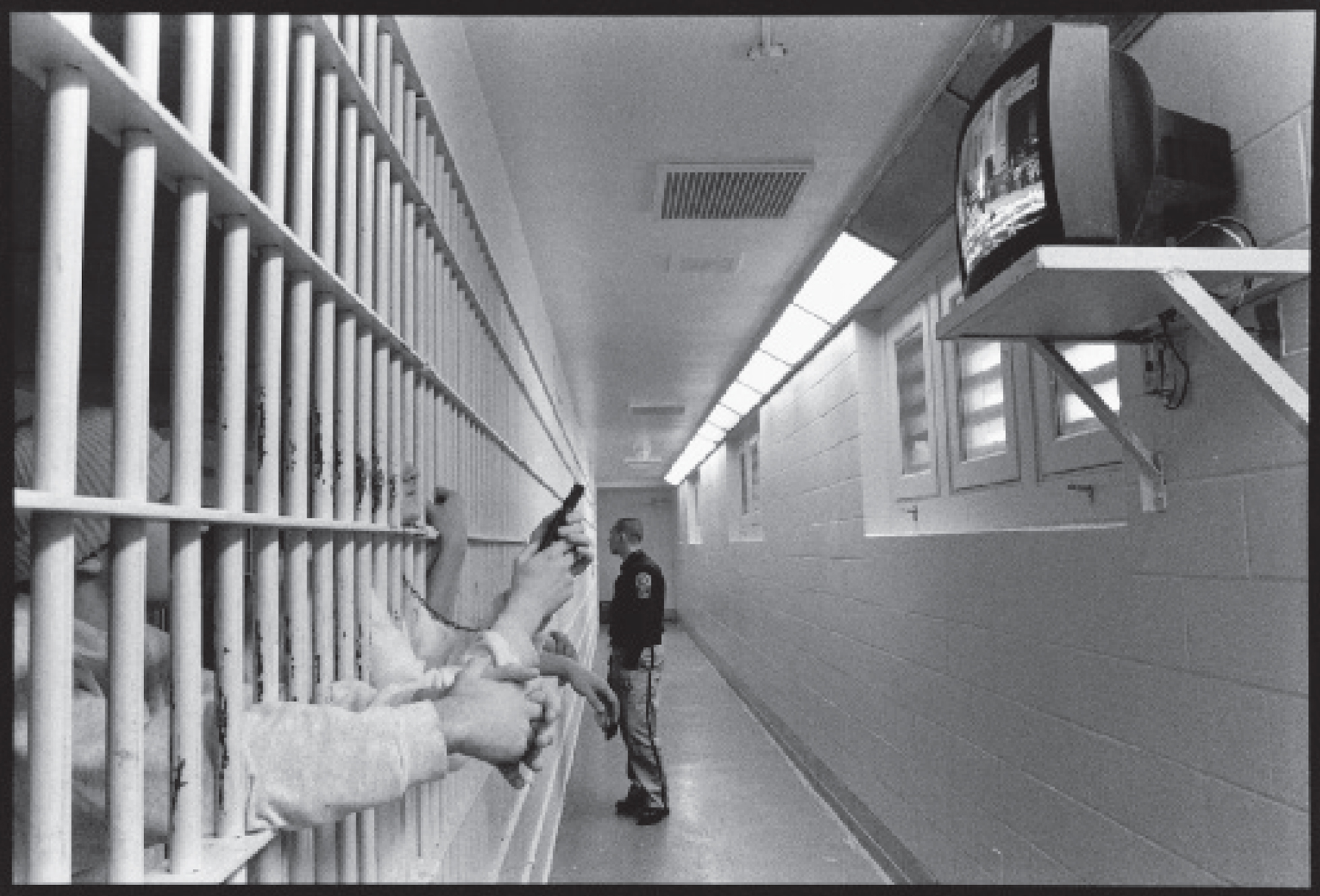

Although I was a clerk in the prison chapel, I always found time for my vices: handball and gambling. The morning I was to report to my first Alcoholics Anonymous meeting (a requirement for my parole), I was in the middle of a handball game. In the joint, if you are playing handball for high stakes and the other guy is losing, you can’t just walk away. You have to give him an opportunity to win back his losses. So I continued to play, but I couldn’t keep my mind on the game. I kept thinking about where I was supposed to be and what I would say when I arrived late.

I walked into the AA meeting an hour late, sweating bullets and looking like a wreck. Everyone stopped talking and stared at me. Prado, the corrections officer who was running the meeting, called me outside. He was a big guy and known as a hard-ass. He asked me why I’d come late. I told him that I’d been at work in the chapel and couldn’t leave.

“Don’t bullshit me,” he said. “I saw you on the handball courts an hour ago.” He gave me a stern warning not to lie to him again.

When I went into the meeting and sat down, I noticed several men in civilian clothes. They were AA volunteers there to tell us their stories. The more I heard them speak, the more I felt as if I had known them all my life. I had done and said the same things and told the same lies when I was out drinking and getting loaded. The only difference was that I had belonged to a street gang.

At the end of the meeting, everyone came by and welcomed me, even Prado. That day, I became a part of a group that knew me better than my own family, and I knew that I would continue coming back, not for the Board of Parole Terms, but for myself.

Through the years I learned that Prado wasn’t the hard-ass I’d thought he was. He, too, was from the streets of East LA and had a brother who was doing time. Each Sunday morning he would show up with pan dulces (Mexican sweet breads) or doughnuts. He and I were never homeboys — there is always that line between guard and con — but he was able to see me as more than a prisoner, and I was able to see him as more than a guard.

One day we learned that Prado would no longer be with us at meetings: the guards’ union wouldn’t let him come in during his off hours without pay. At our last meeting together, he passed me a kite (a note). In it, he said that on the first day we’d met, he’d thought that I was going to be trouble; that I would be full of excuses.

That was more than ten years ago. I am still going to AA.

R. Cabrera

Calipatria, California

As an addiction counselor, I have the pleasure of listening to excuses all day long. Without excuses, there would be no addictions. They keep us from seeing the truth.

My own excuses for my drinking were innovative and lengthy. Once, when confronted by a friend about my behavior the night before, I lashed out at him: It was my birthday, for God’s sake! Everyone makes a fool of themselves on their birthday. And I hadn’t gotten hurt, so what was the big deal? Besides, I had just received a good grade on a paper, and I was celebrating.

I recently met with a young woman whose probation officer had made her come to counseling. She wasn’t happy to be there and was not an easy person to like. She said her probation officer had singled her out because their personalities clashed. When I asked if she wanted to be in counseling, she looked at the floor and said, “I don’t really have a choice, do I?” She told me she had lost her kids to Social Services — just because she had left them alone for a few hours. Wasn’t that better than using in front of them?

“Besides,” she said, “Social Services take your kids away for anything nowadays.”

I sat there imagining all these excuses swirling around in her head, ready to make her feel better about her life. How could I get through them?

I asked if she had any hope that she could quit. She looked me straight in the eye and said, “No.” For that tiny second of eye contact, though, there was a connection. At least now I had something to work with.

Mary Miceli-Wink

De Pere, Wisconsin

In my adolescence, my mother threatened to turn me out of the house and disown me if I became pregnant before getting married. I never doubted the seriousness of her threat. I was petrified, and that fear had the effect my mother wanted. I did not have children until after I’d married.

The day of my daughter’s baptism, my aunt and uncle were proudly showing off pictures of their first grandchild, born out of wedlock. Seeing everyone ooh and aah over the pictures, my mother flew into a rage: at her niece for refusing to marry the man who had fathered her child; at her brother and his wife for refusing to hang their heads in shame; and, most of all, at her own mother for smiling at those snapshots.

I took care never to mention the outburst to my mother, much less demand an explanation. But I told myself there must have been something painful in her past to justify it. I imagined that she’d had a lover in the ten long years between her high-school graduation and her wedding day. Maybe her parents had convinced her to give up her first — and most precious — baby for adoption. Maybe I was not her oldest child.

The thought of having a half-sibling somewhere added romance to the story of my dull suburban upbringing. I suspected I had guessed my mother’s secret, but I said nothing for sixteen years.

Recently I learned that my mother walked down the aisle a virgin. There was no tragic love affair, no fall from grace, and no illegitimate child. For sixteen years I had been feeling sorry for my mother, hoping that one day she would confide in me, hoping that she was not the boring, conventional woman she seemed, hoping that she had some excuse.

Name Withheld

It was a humid July day in 1964, and my Uncle Eddie would be driving all the way from Chicago to our shabby house in Wisconsin to visit.

The last time Eddie had visited, he’d brought large vinyl dolls for my sister and me. I was four years old, and I ran upstairs to hide “Penny” in the closet before my mischievous older brother could pull her head off. Uncle Eddie followed me upstairs and cornered me in the closet, between the shoes and clothes racks. He smelled of tobacco, Old Spice, and whiskey. He put one hand across my mouth and the other up my dress and inside my panties. I was terrified. He made me promise not to tell, and I never did. But I vowed privately that I would not be at the house for his next visit.

Now I had to contrive an excuse not to be home. It had to be airtight, as attendance at family gatherings was mandatory. School, grades, and educational activities took priority in our household, so I said there was a meeting at the library that night for all students in the Reading Club. “If I don’t go,” I lied, “I could lose a whole grade point!”

I was excused that night, and other nights like it, for variations on the same theme. My sister Debbie, however, was short on excuses. She was home for all of Eddie’s visits. Three years later, after several suicide attempts, she wound up in the state mental hospital.

L.J.

Woodland Hills, California

When I was sixteen, I had a hard time understanding why my parents remained married. One morning, my mom was leaning in close to the mirror, looking at her eye, which would not shut all the way. She noticed me watching and said, “This eye hasn’t closed right since the night your father hit me.”

I remembered that night. He had already had his usual four or five vodka-and-waters, tall. He was standing over my mom and yelling in her face. I tried to intervene. Realizing he was too drunk to fight me, he played a mind game instead: There was a large knife on the kitchen counter. He told me that if I wanted him to leave my mom alone, I should grab the knife and try to stop him.

“Do I dare turn my back?” he said. “No, because you’re my daughter. You’re like me. You’ll use the knife.”

With a mixture of fear, pride, and self-loathing, I told my dad to look over his shoulder in the future. Then my mother sent me to my room.

Now, looking at my mother’s damaged eye, I asked, “Why don’t you leave him?”

Her answer was simple. “We’re lucky. Some drunks can’t hold a job. Your dad still works.”

Danita L.

Grand Blanc, Michigan

“Why don’t we live at Daddy’s anymore?” Nolan asks.

I glance in my rearview mirror and repeat what my therapist has taught me: “I like your daddy. I just didn’t like living with your daddy.”

I’ve said this twice before. Today Nolan pushes further: “But why didn’t you like living with Daddy?”

I grasp for an answer that might be both truthful and appropriate for a four-year-old. “You know how Daddy likes watching the news all the time?”

“Yeah.”

“And you know how I don’t even like TV?”

“Yeah?”

“Daddy and I couldn’t agree about that. If I lived with him, poor Daddy couldn’t watch his news.”

Nolan thinks about this for a second and then mutters, “Poor Daddy.”

I have a better answer, one that Nolan might understand in a couple of decades. It’s about the time a chipmunk got in through the sliding glass doors. Nolan and I chased him with cupped hands, laughing and squealing when he scurried the wrong way. Playing “big-game hunters,” we stalked him conspiratorially, winking and mouthing instructions to each other. Nolan had never seemed so intensely alive and beautiful.

Then his father came in. “What the hell’s going on?” he said.

“A chipmunk!” I laughed and shrugged.

With furious intensity, my husband began lifting chairs and small tables, trying in vain to capture the trembling chipmunk, which only skittered into a different corner. “Jesus Christ!” He stamped and pounced.

Nolan crawled into my arms, suddenly afraid of whatever had compelled his dad to such ferocity.

I think my husband saw how ridiculous and out of proportion his reaction was, because he tried to blame me. “You’re not helping me, God damn it!”

“It’s just a chipmunk,” I said calmly. “We’re getting him.”

He stormed out of the room. I knew then that he and I would always see the world differently.

How could I ever explain this? I left my husband because of a chipmunk.

Name Withheld

In 1975, when I was seventeen, I flew to Paris to visit my friend Mina, who was born in Lebanon but lived with her mother in France. I had not seen Mina since we’d been grade-school buddies in Africa five years earlier. At the airport I almost didn’t recognize her. She looked exotic, with her kohl-lined eyes and long, frizzy hair.

Mina and I shared a bed in their tiny apartment. My first night there, she sat up wild-eyed, obviously having a nightmare. Scared, I held her hands until she went back to sleep.

The following morning I asked Mina to go sightseeing with me, but she made an excuse not to go. I asked her again the next day and the day after that, but she always had a ready explanation for why she couldn’t go out.

I learned to explore Paris on my own, leaving early and returning to Mina’s apartment in the evening for dinner and a place to sleep. On my last day in Paris, I asked Mina again if she would go with me, and she agreed. We’d been out for about an hour when she panicked and returned home.

I later learned the reason for Mina’s behavior: Six months before my visit, Mina and her mom had been in Lebanon to see her older brother. They had gone out for a drive and accidentally ended up at a checkpoint patrolled by Palestinian soldiers. Her brother panicked and tried to turn the car around, but a soldier shot him in the head. He died in his mother’s lap. Mina was sitting in the back seat.

Katy Moore-Kozachik

Fairfax, California

He’s cute, in a little-boy sort of way: blond hair hanging over brilliant blue eyes; a round baby face made more mature by a scruffy blond beard. And he’s so much fun to be with.

It won’t matter that he’s younger than I am. He loves me, and he wants children right away. After all, I’m thirty-one, and my clock is ticking. It’s time I settled down and started a family.

I don’t think I really love him, but I like him. And did I mention that he’s fun?

I love his parents. They treat me like a daughter already. And I’m finally going to have a great last name. (My last husband’s was awful; what was I thinking?)

I slide my hand down my ivory dress, grasp the nosegay of flowers more firmly, and start down the aisle. When the moment comes, I hesitate only a fraction of a second before I say, “I do.”

Joyce DeArmond

Urbana, Ohio

Suddenly it’s spring again. The birds sing, and my neighbors come out of their houses and wonder at the absence of snow. I know I should be glad, but I shrink from the spring. The brilliant sun pours through my windows, revealing the orange juice stuck to the kitchen floor. My sad little garden calls out to me like a neglected child. My own children are inside, plugged into video games, unmoved by the warm weather.

I send my children outside to play, and then I clear the leaves from my garden, exposing a tiny crocus. I should see this as a sign of hope, but instead I’m overwhelmed. It’s not just the demands and responsibilities that come with being a mother. It’s the feeling of having to do it well that exhausts me. The idea of raising these children so they become responsible, well-adjusted adults makes me want to go to sleep for a long time.

So as the sun comes out, and the world opens up expectantly, I long for a rainy day: an excuse just to sit and not try so hard to get it right.

Lucy Garbus

Florence, Massachusetts

It was just before Christmas vacation. I should have been feeling relief at having survived my first semester in high school, but instead I was filled with apprehension. In my purse I carried a strip of black velvet I had fashioned into an armband to mourn the soldiers and civilians who’d been killed in Vietnam. More than sixty students had agreed to carry out this demonstration.

Although I was passionate about the cause, on that morning all I could think about was the school board’s threat to suspend anyone wearing an armband. My parents, too, had forbidden me to participate. “Your father has not decided yet how we feel about this war,” my mother said.

By the end of the day, only a handful of students wore the armbands. All were expelled. My armband remained safely in my purse. Over the next few years, the expelled students carried their case all the way to the Supreme Court and won.

Many years later, my son read about their case in high school: Tinker v. Des Moines Board of Education.

“Did you know those kids?” he asked me.

“Yes, they were friends of mine, and I was at some of the planning meetings for the armband demonstration.”

“Did you wear one?”

“No,” I admitted.

“Why not?”

I had waited almost thirty years for this question. I wanted to explain that I was so shy I never said a word at the protest meetings. The other kids didn’t even know my name. I wanted to explain that this was 1965: before the Chicago convention, Woodstock, Kent State, and the draft lottery that would affect every boy in my school. No one objected when the football coach made the boys chant, “Beat Viet Cong,” while they did jumping jacks.

But I said none of those things. There was, after all, only one true answer. “I didn’t have the courage.”

“But you did protest the Vietnam War, didn’t you?” my son asked hopefully.

“Sure,” I answered. “Lots of times.” In my mind, I added, Safely, anonymously, in huge crowds.

He seemed satisfied.

It’s now ten years later. My son, not afraid of anything, is going to New York City to protest the war in Iraq. He invites me to meet him at the train, but I tell him I have other plans.

On Saturday afternoons, demonstrators for and against the war have been gathering at the intersection of Main Street and State Road. For weeks now I have been contributing a honk and a wave to the antiwar side. Today I will join them.

I get friendly nods as I merge into the motley group. Someone hands me a sign with a United Nations emblem on it. As motorists drive by, I make eye contact and wave to people I know. They wave back or give a peace sign.

I don’t delude myself. This is no act of courage. Compared to Roosevelt High School in 1965, Main Street is a cakewalk. It would be great to be in New York, protesting on a grand scale on this sunny afternoon. But for me, today, I need to be here, in my town, where people know my name.

Dianna Downing

Monterey, Massachusetts