THIS MORNING I lay under a mosquito net and whispered with my wife as pigeons scratched and cooed on our corrugated-tin roof. Cocks crowed, mangy dogs barked in adjacent fields, and a grandmother with a tattered dress and a beatific, nine-toothed smile swept fallen mango leaves from the ground just outside our door. The ecstatic drumbeats from an all-night Vodou fête had stopped. The seven insect bites on my ankles itched, and I worried the mosquitoes might have injected into my bloodstream some lymphatic filarial parasites (tiny worms, basically) that would trigger the extreme enlargement and deformation of my scrotum.

Today I turned thirty. The glimmering, conquering vision that I once had of myself at this age has not materialized. Ten days after arriving in Haiti, my wife and I are living in an eight-by-ten-foot room with a bed, chair, small table, gas lamp, and three-gallon water filter. The room is one of four in a square concrete house that we share with three generations of a Haitian family. The decorations they’ve provided for us include a 2003 calendar with a slinky pop star in leather pants holding a Pepsi, and two identical cloth prints of a porcelain-skinned Jesus with reddish hair holding a tiny lamb.

Minutes after stepping outside this morning, I heard activity in a nearby field and walked over. Laughing boisterously, a neighbor handed me his six-foot-long hoe, its smooth handle made from a tree branch, and suddenly I was working in a farm field for the first time in my life, preparing holes to receive three seeds of pwa konni (a type of bean). With each swing, the soft skin of my hands felt a harsh, rewarding tug.

I returned home for breakfast: coffee ground by mortar and pestle and spaghetti noodles with a thin, oily tomato sauce. I gave my last few bites to the neighbor’s nephew, an eleven-year-old boy who had just taught me how to swing a hoe. All food is shared here, the plates passed around during a meal until family, friends, and even animals have eaten.

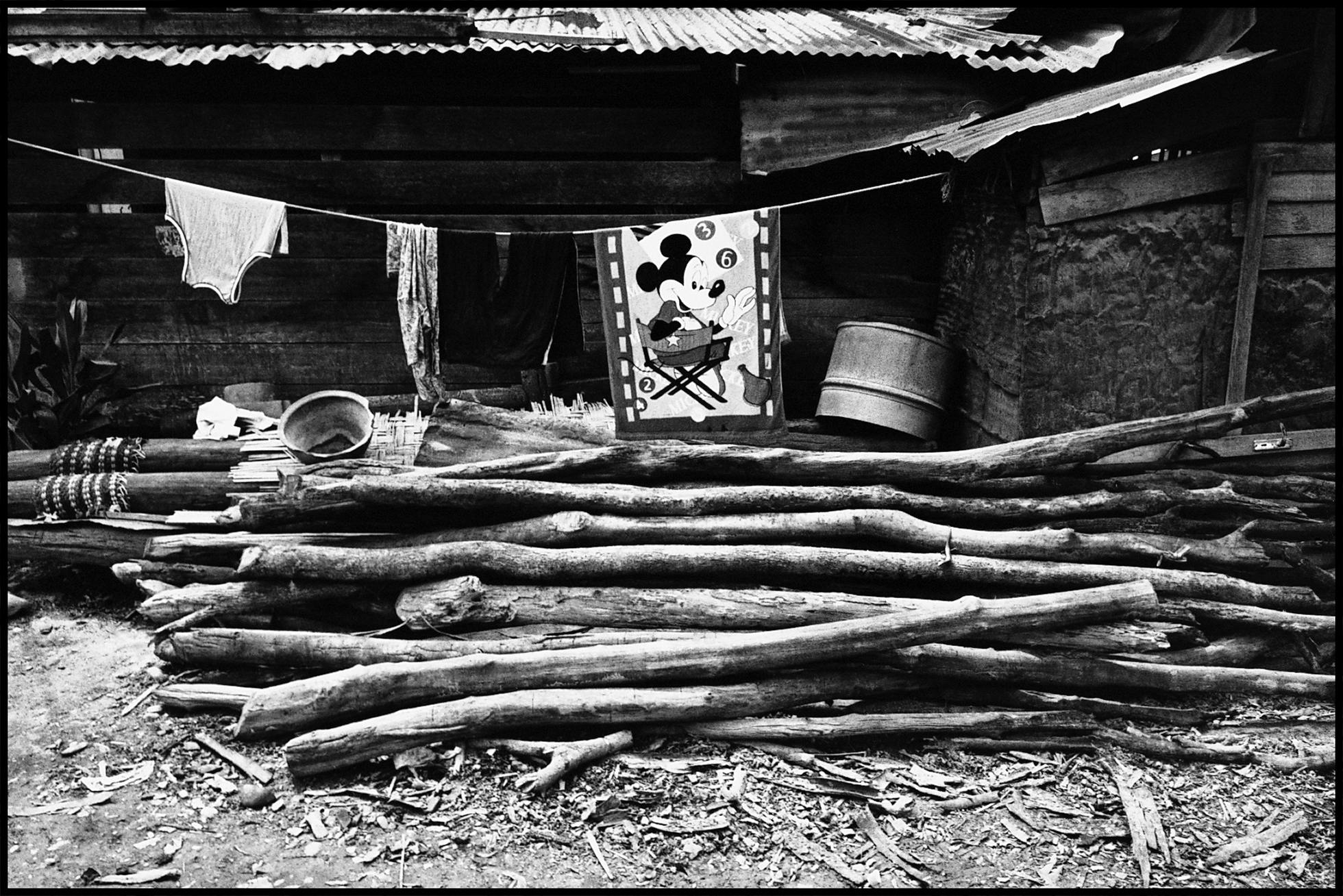

After breakfast, I accepted from the neighbor two fransik mangoes: a thank-you, I think, for my clumsy labor in his field. A rambunctious four-year-old boy wearing only a blue-and-white-checked school shirt sprinted past me, his little uncircumcised penis bouncing merrily along. He was going to fetch a gallon of water at a pump a hundred yards down the dirt path. He’s the youngest member of the family I’m staying with. They live on about a quarter acre of dirt and pebbles with coconut, mango, lime, and other tropical trees. Beautiful, lush shades of green provide the illusion of prosperity. In addition to the concrete main house, there is a second house of woven wood and an outhouse of palm leaves. Six turkeys, three chickens, two roosters, and four guinea hens peck away incessantly in search of seeds. Tied to the trees are a goat and a calf, which I’m told serve as investments/insurance policies, to be sold when money is tight. Two dogs and a cat hover at mealtimes. The family includes a grandfather, a grandmother, a son-in-law, two daughters, and four grandchildren, ages four to twelve, who belong to daughters living elsewhere.

Our tiny village is a couple of hours outside Port-au-Prince. My wife and I are here to work with a small nonprofit organization devoted to literacy and education, but the first step is for us to live in the community and learn Creole. This intense cultural immersion leaves little time for reflection. Still, about once a day something I see jolts me, and I think, Damn. I can’t believe how poor they are.

My reasons for being here are outrageously idealistic. I’m in Haiti to try to love my neighbor. I want to help where other foreigners have hurt or been ineffective. According to many analyses, international development has been an astronomically expensive failure, especially here. Millions of investment dollars have failed to lift Haiti, once the most prosperous of all the New World colonies, out of its status as the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere.

Though my motives may initially seem valiant, they’re also selfish: my own happiness is tainted by the unhappiness of others, and so by helping them, I help myself. I didn’t want to enter my fourth decade as a passive spectator of global suffering. I want to alleviate, at least for a time, at least to some tiny extent, the blatant mistakes of my nation (which are also my own). Also, I’ve found hope in Jesus’ words and life, and I want to follow his injunction to show compassion for the suffering. I hope this is love, though sometimes I think it’s just selfishness dressed up in saint’s clothing.

After breakfast, my wife and I see a baby boy from the neighborhood wobbling around with a bellybutton the size of half a banana. The problem is apparently not serious (except aesthetically) and often goes away after a few years. My wife and I have talked of having a child here — though success is not a given, with the possibility of little worms swimming toward my testicles as I write. But when we retreated into our room for a few minutes, my wife confessed, with some sadness, “I don’t want to have a baby with a bellybutton like that.”

Late this morning I took a small bull to get water, and it dragged me through a muddy canal. Then I took a large cow to get water. When it, too, suddenly started running, I sprinted to keep up, yanking futilely on the rope. A neighbor screamed something to me in Creole. The rope had burned my hands before I figured out that “Lage l! Lage l!” means “Let it go! Let it go!”

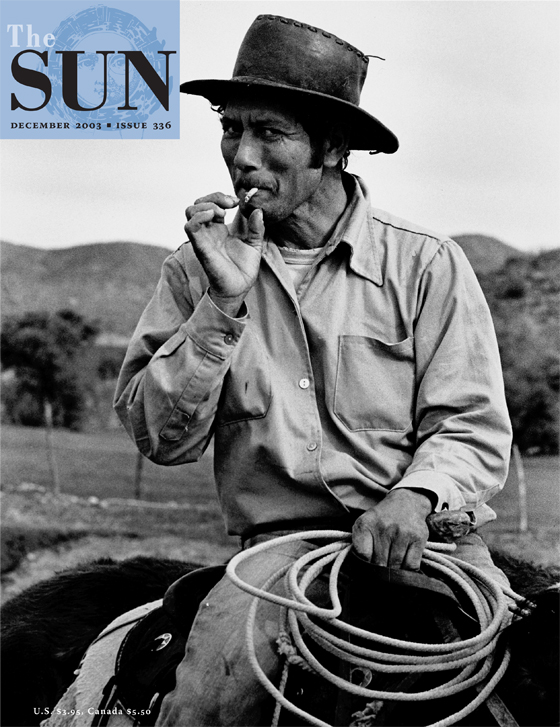

The story made its way quickly through the village. I soon began showing my palms to any who wanted to see the effects on soft pink hands of trying to rein in a runaway cow. I don’t mind. Five hundred years ago, Africans began to be imported to this island to bear the calluses and the burdens, while soft pink hands counted the profits.

Back at the house, my wife gave me a tin coffee cup for my birthday — we’ll use it to drink our filtered water — along with a card that she had decorated with drawings of everyone we live with, including the animals. In the card she was generous to me. She knows that by this age I wanted to be Shakespeare — or at least one of America’s “thirty best writers under thirty.” Instead I’m an apprentice whose words seldom find their way into print. I wanted to be a saint, but instead I muddle along in the same boring selfishness. Jesus started his ministry at thirty and was crucified three years later. If I’m dead at thirty-three, it could well be from swollen testes or, more likely, a car accident on these rugged roads — but I doubt this will qualify me for martyrdom.

LUNCH WAS dense, boiled plantains covered in an oily sauce with a few small chunks of beef, followed by a second course of rice with bean sauce. In a surprising twist, my wife and I have been turning down food — huge portions (for everyone, not just us) of starch piled on sugar piled on starch, with some beans and the occasional mango or coconut thrown in. (Apparently martyrdom through malnutrition isn’t forthcoming either.)

This area has relatively rich soil and adequate water. The people are poor and struggling, but when the weather is right and there aren’t any blights, they get by with their crops of sugar cane, corn, beans, and plantains. It’s not hard to imagine, though, a time when the rains won’t come, and, like many other Haitians, people here would be poor and hungry.

After lunch, a middle-aged woman walked by on the path, a large kivet overflowing with provisions balanced atop her head. She was barefoot and wearing an attractive, though slightly ragged, cream-colored dress cut just below the knee and not zipped up all the way in back. I imagined the dress being given to a secondhand store years ago by an American businesswoman. Used clothing imports often make for humorous sights here: a young mother wearing a “Coming Out Day” shirt; a cocksure young man in a “Jacquelyn’s Bat Mitzvah” T-shirt, complete with Star of David. The Haitian woman in the dress didn’t look funny, though. I couldn’t imagine the dress looking more beautiful on anyone else.

This village has received us with a generosity, warmth, and patience that is somewhat embarrassing, considering my own country’s inhospitality toward Haitians. By chance, the day I resigned from my job to move here, the New York Times ran a front-page photo of Haitians who had just survived a hazardous trip to Florida’s coast on a rickety boat, only to be detained like prisoners to await repatriation.

Not that everyone in Haiti has offered us a warm welcome. Walking down the muddy paths and roads, we often hear cries of “Blan!” which literally means “white,” but also applies to any foreigner. People say it with curiosity or derision — or a mix of the two. Though pale skin can provoke slurs here, it can just as easily open doors to special privileges or trigger a request for money. Last night two guys told me that one of their nation’s founding fathers was ugly because he was so dark: “triple-blackout black.” (The elite in Haiti have typically been mulatto.) This afternoon, however, the same two spoke derisively of an albino Haitian, because he was blan. Each time “Blan!” is hurled my way, I feel vaguely ashamed and impotent. My weak return volley is “My name is Kent. What’s yours?”

This afternoon I invited the neighbor whose field I worked in this morning to play a card game I’d just learned called kazino. He was wearing a hole-riddled black Orlando Predators T-shirt — the only shirt I’ve ever seen him wear. The rules of the card game are simple: if you have an eight in your hand, and there’s an eight on the table, you take the eight off the table and put the two eights in your pile. But he couldn’t catch on. The other guys teased him. I felt bad. At the end of the game, he counted his pile — slowly and not altogether accurately — to twenty-nine. While we were playing, I showed him the effects a morning’s work in his field had had on my hands, and he let me touch his. They were like leather, cured by a lifetime of farming with hoe and machete. They felt like perseverance, like wisdom.

He has something I desperately want and secretly suspect is available only to those who achieve unsurpassed excellence in their field: quiet and unassailable confidence. He knows what he needs to do each day, and he does it with absolute surety.

We sat outside after finishing the card game. The kids were playing and doing chores. They go to school in the mornings — when it’s in session and there’s no teachers’ strike. In the afternoons they have little supervision and regularly play with fire and machetes. A couple of days ago we laughed at a four-year-old who dashed by with a plastic bag over his head — a sin that might get one’s parental license revoked in the U.S.

On first impression, I’m more drawn to these children than I am to American kids, who are often self-centered and whiny. The kids here are happy, active, and curious. They love to sing and dance and tell stories. They’ve taught me the Creole words for all the area’s vegetation and animals. They daily fetch countless gallons of water. From what I hear, it’s normal for them to be beaten occasionally with a switch, though I haven’t seen that happen in our host family. When I accidentally broke one of their toys (a small piece of discarded plastic), they tried for a few minutes to fix it, then ran off to find something else to play with. A dozen rusting D-size batteries, perhaps.

But the four-year-old, the most aggressively curious and hardworking child I’ve ever met, can’t count to three. The seven-year-old, a charming schemer, can barely sound out words in a book. When he does read, it’s to memorize passages from a 1968 textbook written in French — a language that he doesn’t fully understand and likely won’t ever have reason to speak. (The echoes of colonialism are difficult to silence.)

We haven’t faced anything truly heartbreaking yet, at least among our immediate acquaintances. But at the nearest hospital, which we’re told is one of the best in Haiti, I heard the receptionist telling mothers with sick children, “Come back tomorrow, and maybe you’ll get to see a doctor, si Dye vle” — “God willing.” That addendum is attached to any statement having to do with the future, whether plans for a meeting tomorrow morning or the harvest in three months. In this place, the phrase seems alternately a statement of a stark fatalism, a bitter taunt directed toward the Divine, and the most unsentimental confession of faith I’ve ever heard.

We’re coming to care deeply about the people we’ve met here, and a faint and permanent nausea has settled in my stomach — the fear that one of them will become severely ill. Whoever it is won’t get airlifted to Miami, like I would.

Walking back in the glaring afternoon sun from fetching two gallons of water at the well, I stood by and watched a group of twenty kids and adults tease and push a chubby teenager. His tormentors repeated loudly, and taught me how to say, what I presume is the Creole word for “fag.” I then tried lamely to make amends by introducing myself to the teen and asking his name, but I didn’t intervene on his behalf. I walked away, ashamed that unfamiliar circumstances could so easily paralyze me.

Back on our porch, we watched a man walk by wearing only shorts and carrying a machete in his hand. His body was gleaming and beautiful, each muscle sinuous and hard. My various anxieties about living in Haiti have been distilled down to two potent fears: mosquito-borne illnesses and imagined threats to my wife’s physical safety. This culture is more sexually aggressive than ours, and the men’s looks toward her, their unsheathed machetes, and the strength of their bodies have done little to calm my fears.

AT DUSK, my wife and I walked through the sugar-cane fields into town for a weekly meeting of a literary discussion group. The sunset was beautiful through the coconut and mango trees, and a gigantic full moon hung waiting at the other end of the sky. On the way we passed a horse standing in an arid field with only a few dry cornstalks. This was by far the most undernourished animal I’ve seen here. The horse’s head sagged, its ears drooped, and its rib cage pressed against its dirty beige hide. Its hunger and sadness begged for a chapter’s worth of somber Dostoevskian description. But the Haitians we were with made fun of it.

In town, twenty young people had gathered to discuss literature in a classroom buzzing with mosquitoes. All discussion was in Creole. In Haiti, this is a radical approach to learning, since traditional education is still in French, the instruction is heavy-handed (how else does one untrained teacher handle sixty kids?), and lessons consist predominantly of rote memorization. This week’s discussion was about the strength of Achilles, based on a passage from The Iliad. A man in his twenties read the selection aloud, holding the book three inches from his face. (My glasses are such a novelty here that a few days ago the village kids made glasses out of banana leaves to imitate me.)

We made our way home through the dark, puddle-filled streets. A few vendors remained open, selling fried bread or candies, their small stands dimly lit by candles. I counted these as my birthday candles. Haitian male life expectancy — with infant mortality, AIDS, and poverty working their cruel subtraction — is fifty years old. Not too many candles away.

ARRIVING HOME, we find that we have missed the dinner of rice and beans, for which we are thankful, having had too much to eat already. We sit outside under the bright moon, and the grandfather says, as he says every day, “I put in a hard day’s work again today. All day long. Hard, hard work. I have to work all the time.” And he does work hard: I’ve seen him planting seeds by hoe and scaling a fifty-foot coconut tree with his bare hands and feet. But his lament feels more like a sales pitch. Maybe he thinks we can provide access to America’s great wealth. A Haitian we’ve befriended has told us that, whether they admit it or not, all Haitians think this way. I don’t believe this is true, though I don’t doubt it would be true of me, were our circumstances reversed.

Despite the grandfather’s impulse to impose his patriarchal will (particularly on my wife, by making her eat piles of food), he is positioning himself to receive our help because he imagines we hold some power over him. We hold the keys to the kingdom. Everyone is using everyone else, it seems: we’re using the family’s hospitality to learn the language and the culture; the son-in-law uses us to show off to his friends; the grandfather wants to use us as an investment toward a future payoff. This might seem cynical, but it isn’t. It’s real life. Cynical charity is the kind that uses innocent kids and preposterous statements about how you can change a child’s life for a mere dollar a day (nothing else required of you). Real charity, the kind that does more than just relieve one’s conscience, is more complex, more demanding. I vacillate between despair — how could we possibly be of any use here? — and trust that we’re in the right place, for the right reasons, with the right people, and whatever comes of it will be for the better.

While we continue to talk with the grandfather under the stars and moon, the neighborhood children gather and begin to sing and dance and play musical chairs. I get up and play with them for a little while. During a break, I drink a mixture of juice and milk cooled by an ice cube that might contain parasites that will make me sick, but it’s worth the risk; the beverage is outstanding, and besides, it would have been awkward to refuse. I check the time, and immediately a circle of young boys surround me and make me light the Indiglo dial of my watch again and again. Then I go to the outdoor shower at the back of the concrete house and, with a yellow margarine container, scoop water out of a large bucket to wash away the day’s dust and mud. The water is cold, and the moonlight shines brilliantly through the fifteen-foot-long banana leaves fanned out overhead. I never envisioned myself here at thirty, but today there was no place I would rather have been.

After saying bon nuit to everyone, I go to my room. I want to make love with my wife, but she’s already asleep under the mosquito net. She’s not comfortable with our lack of privacy; the walls don’t even go all the way up to the tin roof. Staticky dance music plays on the radio in the next room; the newlywed daughter and son-in-law turn it up each night to cover their urgent breathing.

As I begin to fall asleep, I occasionally jerk awake, gasping for air. This started a few days ago, like a sudden onset of sleep apnea. It’s unsettling. I wonder irrationally if someone has put a curse on the new blans in town.

As I drift farther into sleep, I think of my wife earlier in the evening, acting out and telling, for the tenth time in broken Creole, the story of how I was pulled through the field by the cow while the neighbor yelled, “Lage l! Lage l!” After she was finished, I asked one of the family’s relatives, who lives nearby, whether a cow had ever pulled him like that. He laughed and said, “All the time.”