My mother was standing in front of the open refrigerator in her bathrobe, her face bloodless, almost gray. At her feet were the broken glass of a ketchup bottle, an egg carton spilling eggs, and a quart of orange juice. Her mouth opened and closed, and I could hear a deep rasping as she struggled to breathe.

“I just saw a rat,” she said. “It was there.” She pointed to a bowl of apples on the counter. “It jumped behind the stove. It was watching me,” she said angrily.

I ran to get my father, who banged on the stove and opened the cabinets one by one, taking out the cans and boxes and setting them on the kitchen table. “Aha,” he said. He held up an old bag of peanuts we’d bought at a gas station on a trip to Florida. The bottom had been shredded into long, narrow strips, and the cabinet shelf was a mess of peanut shells and rat droppings.

“I’m going to be sick,” my sister, Emily, said. She was sixteen, just one year older than me. Neither of us wanted breakfast.

“Arnold,” my mother said to our younger brother, “mix me a drink.”

My mother, who had stopped drinking excessively a few years earlier by sheer force of will, allowed herself exactly one drink a day, measured and mixed by my ten-year-old brother, Arnold. He took his job seriously, kept a bartending guide from the 1930s on his bedside table and flipped through it each night to choose his next recipe. If it called for grenadine and we didn’t have it, my mother would buy some the following day, and that night he would mix her a drink: perhaps a bartender’s signature recipe from some long-since-demolished grand hotel: a Berlin Rain, or a Buffalo Hide. Although he’d never tasted alcohol, Arnold knew all the types and grades of Scotch, the many ways to slice a lemon, and the secret to a perfect martini. He made careful notes next to the recipes he’d prepared for my mother: “Never again”; “Less Worcestershire”; “Too sweet”; “Try in a blender.” Her highest praise was simply to take a sip, breathe a sigh, and say, “I do believe I could drink ten of these if you let me.” Arnold would bow his head modestly, his pleasure barely concealed behind a half smile as he wiped his shaker on the white towel reserved specifically for that purpose.

On the morning she saw the rat, Arnold fixed my mother’s drink in a hurry, and she took it without even asking what it was.

“I thought I heard something scratching around last night,” Emily said. “You know, scraping, like the sound of a cat in a litter box. But scarier.”

My mother stiffened on the couch. She held her cocktail glass in both hands and took a slow, conscientious sip.

“It’s getting into and out of the house somehow,” my father said. “We just need to find its point of entry.”

“Or maybe,” my mother said with a shudder, “it lives here.”

The possibility sent a wave of excitement and disgust through us all.

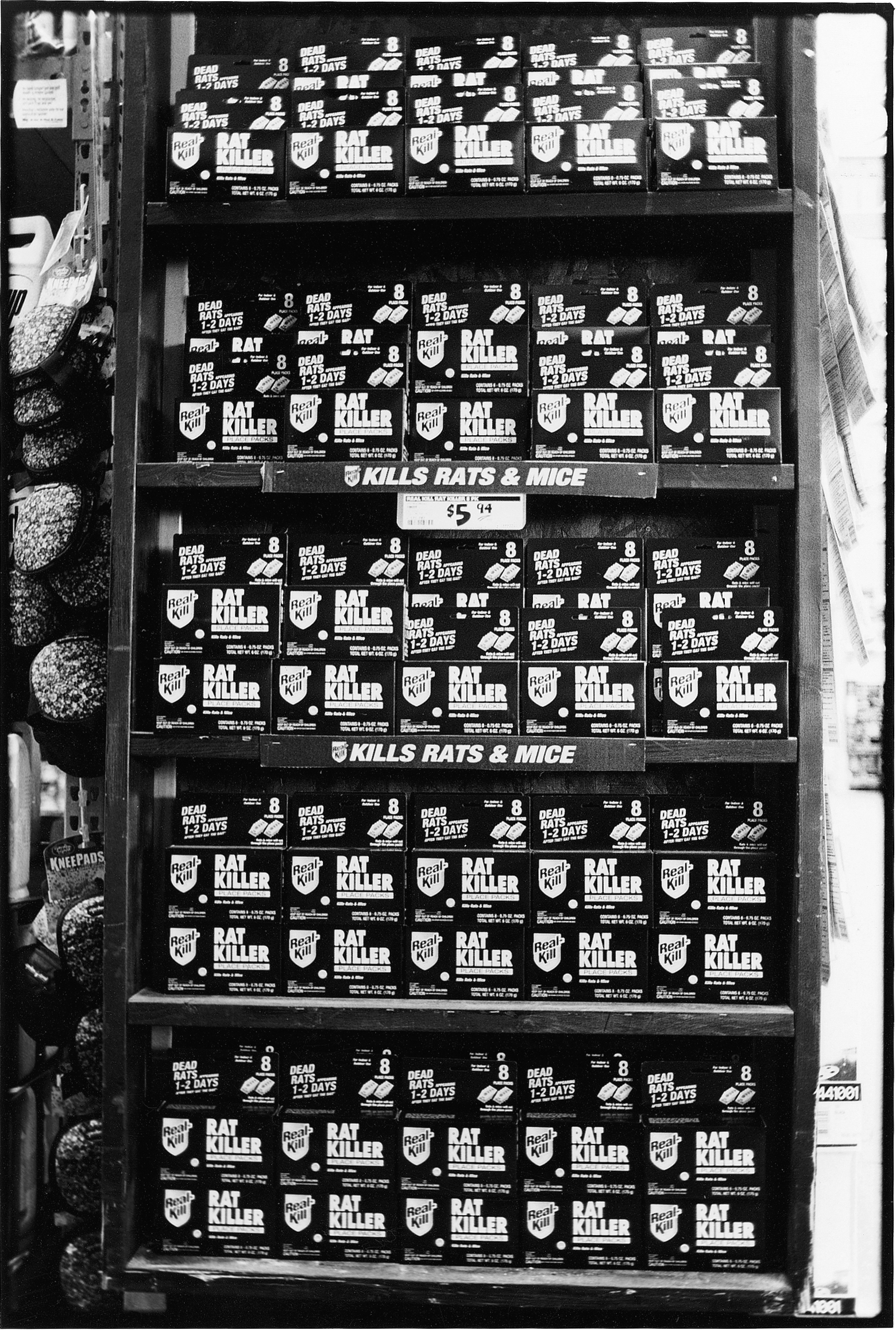

My father returned home from the hardware store with an assortment of rat traps and poisons. Our favorite was a mesh cage about the size of a shoe box with a spring-activated steel door that came down when the bait was taken. “It traps the rat alive,” my brother whispered. There were the standard traps, too, like in old cartoons, with metal arms that sprang down magnificently loud and fast — and hard enough, we later discovered, to decapitate my sister’s old Barbies. Our father placed this arsenal on the dining-room table alongside some house blueprints, crumbling at the edges with age, that he’d dug out of a filing cabinet. We plotted placement strategies the way generals might plot an invasion. The steel-cage trap would go in the attic, the poisons behind cabinets, under furniture, and in the basement and closets. There were just enough of the standard traps for my siblings and me each to place one under our bed. My brother smeared his with peanut butter, my sister baited hers with a thick slab of smoked Gouda, and I set mine with half a gherkin. After that, there was nothing to do but wait.

That afternoon, my sister, my brother, and I were writing on the floor of the garage with colored chalk. It was cold, but we thought that if we stayed out of the house, the rat might come out of hiding and get caught in one of the traps. Emily wrote curse words and warnings to the rat in pig Latin and our parents’ names surrounded by hearts and flowers. I drew a monkey dressed as Sherlock Holmes. My brother drew two rats wrestling.

“They look like they’re humping,” Emily said with a dismissive sneer, standing over him. She rolled her eyes and laughed when she saw his blank expression. “You know: humping? Screwing, for God’s sake! A man gets a hard-on and sticks it into a woman’s vagina,” she said. She made an O with her thumb and forefinger and thrust the index finger of her opposite hand in and out of it. “Get it?” She rapped on the floor of the garage with her knuckles. “Hard like this. If a girl has had her period, and a man has a hard-on, she can get pregnant, provided they’re both old enough to have pubic hair.”

Arnold shook his head in disbelief, and his nostrils flared in resistance.

“It’s true,” she said. “Every living thing was made by fucking: You. Me. Mom. Dad. The rat.”

“Never,” Arnold said. “I don’t believe you.” Arnold looked to me to back him up.

Emily enjoyed lying to him as much as she could, but it was, of course, the truth. I remained silent.

“He gets hard-ons all the time,” she said, pointing at me with her thumb.

I blushed and looked away. I’d hoped no one had noticed, but they happened at the most inopportune times, like during The Waltons, or in the car pool.

Arnold shook his head in disbelief. “You lie,” he said.

Emily gave an exasperated sigh. “Of course you don’t believe me,” she said to him. “Your older brother is supposed to tell you this, but he’s gay.”

This, too, was true. Again, I’d hoped no one knew. I didn’t want to face it myself, but I was undeniably attracted to the guys in the ads for home gyms. I was also turned on when the Hulk changed back into David Banner and found himself in a deserted alley at dawn, shivering and perplexed in his torn clothes. Almost naked. I floated in a guilty stew of strange desires.

That night my mother wouldn’t go near the kitchen, so we decided to cook out, even though it was the middle of February. It fell upon my sister and me to get the fire started, so we bundled up and went out on the deck. The grill was old and had been covered with a tarp since summer.

“Gross,” Emily said when I opened the lid. The inside had never known a brush, and blackened bits of hamburger and carbonized chicken fat clung to the metal grate. It was already dark out, and Emily, who was holding the flashlight, cleared a deck chair of dead leaves and sat.

“I’m sorry if I embarrassed you,” she said.

“I’m not gay,” I said.

“It’s OK if you are,” she said. “Look at me.” She pointed to her body with her mittened hands. My sister weighed 198 pounds. When she wore something tight, her flesh bulged like the top crust of a misshapen soufflé; double chins formed whenever she nodded her head. “I know someone else who’s gay, too,” she said. She paused and looked out to the edge of the woods, which were completely dark. “Herman Sandeldamm.”

Herman was the son of our piano teacher. The Sandeldamms lived up the street from us in a brick two-story house with a muddy pond in back surrounded by a family of plastic ducks and a bust of Bach. Herman’s mother referred to it as the “water feature.” Although my brother and I were still taking lessons, Emily had quit. She’d told our mother that playing scales made her fingers ache, but I suspected it was because she had an unrequited crush on Herman. Although just fifteen, he was talented, probably better than Mrs. Sandeldamm herself. His picture had once appeared on page A5 of the New York Times as the youngest winner of an international piano competition. He was thin and pale, his delicate skin almost transparent, like the tissue paper covering an illustration in an old book. He was like something fragile and priceless that had to be handled with white gloves to prevent it from crumbling. I’d watch him ride by our house on his expensive bike, all whirring gears and ratchets, whizzing by like a hummingbird with mechanical wings, a flash of pumping yellow corduroy pants and bright red rubber rain boots, which he wore even on sunny days. If I got to my lesson early, I might see him playing Liszt in the same lightning-quick, heroically manic way he rode.

“I think Herman likes you,” my sister said.

Ignoring her, I squirted lighter fluid on the leftover charcoal in the grill. A shadow beneath the bars seemed to writhe and slither strangely about. I squinted and bent in for a closer look. When I saw what it was, my hand instinctively flew up to my mouth, and a weak cry squeaked from my throat, like a sound from deep inside an old, rusty pipe.

“What’s the matter?” Emily said.

“It’s in the grill,” I said.

Emily stood, took careful steps toward the grill, and peered in skeptically. She jumped back with a shriek. We threw our arms around each other.

“Light it!” Emily screamed. “Burn it, burn it!”

With trembling fingers, I struck a match against the box and tossed it onto the grill. The match extinguished in midair and landed harmlessly with a plink. We both screamed. I pulled out another match and tried again.

“It’s getting away!” Emily yelled.

A blur of wet gray fur dropped from a hole in the back of the grill, scrambled across the deck railing with the sound of a dog scratching on a door, and was gone.

Back inside, my mother brought me some aspirin and a hot towel for my brow. I lay on the couch with my head propped up on pillows. My family crowded around me.

“You’re white as a sheet,” my mother said.

“Was it a boy rat or a girl rat?” asked my brother.

“The paws,” I said. I took a swallow of camomile tea. “Like hands.” I held up my own hands, the fingers loosely curled. “Soft, pink, almost human. I think it had five fingers.”

“How big was it?” my father asked. I held my hands about six inches apart, then widened them to a foot. “With a tail, like so. The tail was pink, with hairs sprouting from it.”

My brother’s lip curled in disgust. “And the teeth?” he asked.

“It didn’t bare them,” I said. “But its face was —” I couldn’t continue.

“Tell us!” he demanded.

“Cute,” I said.

We were all silent for a moment. Through the sliding glass door, I could still see the open grill, the lid on the railing, the can of lighter fluid lying on its side, the spilled plate of marinated drumsticks and wings, a red pepper, slices of eggplant — peaceful and strangely pretty, like a still life.

“I know what you mean, sweetie,” my mother whispered, kissing me lightly on the forehead. Of course. She had seen it, too.

Then she turned to my father. “Catch it,” she said. “Catch it, and kill it.” Though she’d already had her one drink for the day, she ordered Arnold to make her another.

For the next few days, we spoke in hushed voices and kept the stereo and television off. The house was quiet, dull, still, as if we were snowed in. Every scratch or creak put us on edge. My father closed the windows in the basement and checked the walls for holes: although he hadn’t touched his hobby set of oil paints in years, he was worried the rat would chew his old canvases to bits to line its nest. My mother cleaned out the kitchen cabinets. Emily and I sprayed down the bathrooms with bleach and reorganized the linen closet. Arnold reassembled the decapitated Barbies with parts from his dismembered GI Joes: A muscled torso sprouted a smiling female head with long, blond, California-girl hair. A nude female body with hard, nippleless breasts supported a bearded, buzz-cut head. Dressed in yellow bathing suits and military fatigues, they rode in a pink convertible stocked with Uzis and grenades.

“Rat check,” my father would say when he came home from work. And we would run to the various traps to see if we’d caught the rat. We slept lightly, each hoping and fearing that we would hear the slam of the trap in the night and be the one to go running with the news that the rat at last was dead. But we found nothing, heard nothing.

At dinner the next day, we stabbed listlessly at our spaghetti. I imagined that the rat had nibbled the dried pasta in the night, then nestled and slept on my plate, leaving a greasy film in the shape of its body. Emily’s eyes were red-rimmed and had dull gray circles underneath. She’d been up late reading library books about the history of pestilence. “It doesn’t matter what we do,” she announced. “Lock the doors, stuff the cracks, close the windows: it’s no use. Rats can chew through anything. Even concrete and steel. Their teeth are hard, but their skeletons are soft. They can literally mush themselves flat and slip through a hole that’s barely bigger than their spine. In London and New York, you’re never more than ten feet away from a rat.”

“They just come inside for food,” my mother said weakly, “and then leave.”

Emily shook her head. “They live where it’s warm. In the Middle Ages, rats were famous for creeping up on you while you slept and eating the crumbs from the corners of your mouth.”

My mother threw down her fork and put her head in her hands. We gathered around her and stroked her back.

One Saturday afternoon, about a week after my mother had first seen the rat, I flung myself onto my parents’ bed and lay perfectly still. My mother was seated at her vanity, humming softly to an oldies station on her clock radio, cleaning out a drawer of empty lipsticks, crumpled tissues, and worn nail files. The late-winter sun slanted through the blinds, casting golden bars across the white carpet, so bright that I could still see their pattern after I shut my eyes. I clicked my heels together to the beat of the Supremes’ “Where Did Our Love Go?” I wasn’t supposed to have shoes on the bed, and I was waiting for my mother to say something, but she just smiled vaguely at me and continued with her task. In front of her was a fuzzy brown cocktail.

I turned over on my stomach and rested my chin on my flattened hands. “My whole head hurts,” I said. I wanted to scrape my mind clean.

“You’ll lose six tablespoons of blood for every aspirin you take. How about a warm bath?”

I shook my head and sighed. “What makes people want to have sex?”

If my mother was surprised by my question, she did not show it. “If two people love each other very much,” she said, “they might want to express it in that way. Or sometimes there’s money involved. Or people want children. It can also be a status thing. The uninhibited can use it to get ahead.”

“I don’t think I’ll ever want to,” I said.

“You may change your mind one day,” my mother said. “Anyway, you’d make a fine priest, so don’t worry about it. Has the rat got you upset again?”

I nodded. A hot tear streamed down my face. I shut my eyes tight and saw a progression of filthy images: the wet pink flesh of unnamable orifices; hairs on rat tails; Herman Sandeldamm grinning at me, holding his huge penis, worn and barnacled like the piling of a pier. The ice tinkled in my mother’s glass as she took a long sip.

That week, when my brother and I arrived at the Sandeldamms’ for our lesson, Arnold was taken immediately into the music room while I sat on a wooden bench in the hallway. Through lace curtains and wavy glass I could see puffy, pointless snowflakes drifting to the ground and melting. I could hear Mrs. Sandeldamm tapping out time on the music stand, expressing dissatisfaction with my brother’s playing, flipping the pages of the Chatterbox songbook back to the beginning and telling him to play it again, this time with “more crispness.” I stared at the cover of my sheet music for “Balloons for Sale”: a man with a bow tie and handlebar mustache, holding a bunch of balloons in one hand and tipping his straw-boater hat with the other.

On the wall across from me, in an elaborate gold frame, was a new photograph of Herman receiving an award. He wasn’t smiling, but looked nonchalant and somewhat suspicious of the presenter — and rather dashing and rebellious, I thought, in his blue blazer and club tie. Feeling restless, I climbed the stairs to the hallway above. One door had a photograph taped to it: industrial workers in white jumpsuits sorting thousands of cupcakes on conveyor belts. I knocked.

“Come in,” Herman said.

I opened the door. His room was clean and nearly empty, as spare as a monk’s cell: an iron bed with white sheets, a small red carpet on the wooden floor, and a folding lawn chair in which Herman sat with a book in his lap. A heavy blanket was draped around his shoulders like a prince’s robe, and he held it closed at his chest with his long, Botticelli fingers. His round, heavy head seemed precariously balanced on his thin neck and shoulders.

“Hey,” he said. “You look tired.”

“We have a rat at our house,” I said.

“Hmm. Did you practice this week?”

I shook my head.

“Shame,” he said. “Do you hear that?”

We listened to the sounds of my brother plunking away.

“Your brother has some very nice phrasing. He’ll do well with Schubert.”

I shrugged.

Herman motioned for me to hand him “Balloons for Sale,” and he flipped through the pages, humming softly. “It’s perfectly nice. Why wouldn’t you want to practice this?”

I shrugged again. I was tempted to use the rat as an excuse, but the truth was, even without the rat, I hated the piano.

“Concentrate more on your phrasing today. Try: ‘Balloons for sale / Red and blue and green / Balloons for sale / Buy them all from me.’ Think of wind and air; think of what’s inside those balloons.”

I was flattered: he’d been listening to me play. We are gay people, I thought suddenly. We are two gay people together. It was scary, but better than being alone.

“Do you want to go for a walk?” I asked.

“Sure,” he said. He dog-eared his page in the book and threw on a coat. We went out the back, through the yard, past the water feature (covered now by a moldy blue plastic tarp), through a gate in the wooden fence, and into the woods behind his house. Herman’s blue down coat was too small for him: the sleeves stopped before his wrists, and the hem hung an inch above his waist. The snow had passed, but it was still cold out.

We came to a chain-link fence, beyond which was a highway. “Whooo!” he yelled at the passing cars. He grabbed the fence with both hands and shook it. He leaned his head against the links and said to me sadly: “In Cuba, they smoke and drink, and they live, really live.”

“Do you drink?” I asked.

“No,” he said, “but I want to start.”

“My brother knows how to mix drinks. My parents are going out for dinner on Friday. Come over.”

He blew on his hands and shoved them into the pockets of his coat. His hair was clean and the color of a roasted peanut; a few stray hairs floated apart from the others and fell into his pale face. I tucked them behind his ear with a quick, motherlike motion of my hand.

“Hmph,” he said, and we started back: it was nearly time for my lesson.

At the house he left me in the hallway to go back upstairs. “Play well,” he said.

During my lesson, Mrs. Sandeldamm, in her pink sweat shirt with the silver pin in the shape of a treble clef, tapped out the rhythm on the piano bench with a pencil; she took me back to the beginning many times, telling me to play with closer technique and looser fingers. I could not concentrate. The notes in front of me were a blur, as though I were seeing them through some strange new lens.

On Friday, my parents went to the city for dinner as planned. My brother and I filled the ice bucket so that everything would be ready when Herman arrived. Our liquor cabinet was on wheels — more cart than cabinet, really. It reminded me of a jeweler’s case. The bottles inside seemed as faceted as diamonds, though some of the labels were old and peeling, with pictures of tree branches, turkeys, and ruins. There was a bottle in the shape of a cluster of grapes and another concealed in a velvet bag. Set into the floor of the cabinet, next to a well for the ice bucket, was a shiny clock with sparkling hands. It had been stuck on 6:15 for as long as I could remember. My mother told us that she’d broken it when she’d (nearly) stopped drinking, so that it would cease chiming out “Enchantment” at six every day, signaling the start of cocktail hour.

My brother wheeled out the cart and lifted the glass cover. A wonderful smell hit us: warm wood, almonds, spicy olives, vanilla, and brandy.

“I don’t even know if he’s coming,” I said.

“He’s coming,” Emily said.

We were watching the silent film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari on public television when the doorbell rang. Herman was there in his too-small blue down coat and matching cap.

“Welcome,” my brother said, politely and formally. He took Herman’s coat and hung it in the hall closet, then led Herman into the living room and invited him to sit on the couch. My brother went to the liquor cart and said, with a deferential bow of his head, “What can I get you to drink?”

“Hmm,” Herman said. “Chocolate liqueur?”

My brother lifted an opaque white bottle and showed Herman the label as if it were a fine wine. He poured us each a splash over a single ice cube in a cocktail glass.

Emily rolled her eyes. “That’s not enough,” she said. She grabbed two large tumblers, dropped in a few ice cubes, and filled both to the rim with the dark, syrupy liquid. Then she handed them to us with white paper napkins wrapped around the base. I took a nervous sip.

“Yuck,” I said. “It tastes like old fruitcake.” I drew a bigger swallow and then another, trying to think of pancakes and chocolate fondue. Herman sat with his legs crossed at the knee, shook the ice in his glass — to cool the drink — and casually sipped from it.

“It doesn’t taste as bad if you hold your breath,” Emily said.

I tried it: a few minutes later, our glasses were empty.

“I can’t feel anything,” Herman said plainly. Emily took our glasses back to the liquor cabinet. “Not the chocolate again,” Herman said.

Emily rummaged around and pulled out the vodka. She put fresh ice in our glasses, and a bit of soda water from the spritzer, then filled them to the rim with vodka, topping the drinks with maraschino cherries and a dash of the bright pink liquid they came in.

“Mmm,” said Herman. “I like this much better.”

“Me, too,” I said.

Emily put on a Dionne Warwick record from my mother’s collection. “Do you feel anything yet?” she asked Herman.

He shook his head.

“Maybe alcohol has no effect on us,” I suggested cautiously. “Perhaps it’s just the way we’re wired.” We drank our drinks and waited. On TV, people wandered through the streets of their crooked little dream town to the fair. The somnambulist opened his syrupy eyes and gave predictions. Herman laughed when the words “Time is short. You die at dawn” flashed on the screen. We looked at him: had we missed something?

“I think I feel it,” he explained.

“Ah,” I said and closed my eyes. I thought I might be rocking back and forth, not unpleasantly, but it was hard to tell. Dionne Warwick was singing, “You’ll never get to heaven if you break my heart.” On TV, no one stopped the sleepwalker as he shambled through town; no one called out or said anything to him. “He’s not going anywhere!” I shouted. It was a joke, but I’d forgotten why it was funny. My voice sounded inexplicably high and loud. I tried to imitate the sleepwalker — arms at my sides, eyes wide open — but the carpet seemed to rush up to block my way. I was on the ground, looking up at my sister’s scowling eyes. “I don’t want to die,” I whispered.

“Don’t be silly,” she said with an icy smile. “You’re just drunk.”

She guided Herman and me down to the basement. I hadn’t been down there since our house had been invaded by the rat: the bare bulb, the metal shelves with my father’s old painting supplies, our disemboweled orange couch with its broken springs and bits of stuffing hanging out. Emily unfolded our small one-person trampoline, in storage for winter. Herman bounced on it a few times, then dropped onto his back and lay still. I stumbled over to him, tried to climb onto the trampoline, then gave up and slid underneath, where I lay on the dirty floor, looking up. Herman’s body made the trampoline sag like the swollen stomach of a pregnant woman. The door slammed above, and I heard the sounds of the bolt sliding and my brother and sister laughing in the kitchen.

“Hello down there,” Herman whispered through the black netting.

I couldn’t see him very well, but his voice was very close. “Hello up there,” I said. “We’re locked in.”

“Like pandas for the mating.”

I looked around at our cage: a black puddle, some wet leaves, an old deflated soccer ball, the bars of rat poison like chunky green soap. I felt the back of Herman’s head, a solid bulge in the net. I cupped my hand around it for a moment, as if to read the bumps and ridges of his skull.

“I’m drunk,” he said.

I didn’t say anything. I didn’t move. My heart was beating fast, and my throat was dry. I wanted to get closer to him, but I was scared: scared he would leave; scared he would stay. I remembered the rat. I imagined it scuttling toward me across the basement floor to lick the sweet booze from the corners of my mouth.

With some effort I climbed up on the trampoline. The sagging net pushed us close together. He was warm, and his hair smelled like burnt cotton candy. I put my arms around him, but when I tried to kiss his neck — at the spot where his throat sank into his collarbone — our skulls bumped together with a noise.

“I’m sorry,” he said and laughed, rubbing the spot on my scalp where our heads had hit. He kissed my forehead, unbuttoned his pants, and slid his yellow corduroys down to his red boots. I traced the waistband of his Fruit-of-the-Looms with my thumb, creeping shyly, heart pounding, both of us on the verge of laughter — until I touched his penis, and a jolt of electricity hit my gut. I held it in my hands: so new, but so familiar.

When we came back upstairs, the door was unlocked, and the house was quiet. My parents were in the living room. My mother sat Indian-style on the couch, squinting lazily and puffing on my father’s pipe, a halo of spicy blue smoke around her head and a big glass of red wine between her thighs. My father sat on the floor in front of her, busily drawing in a sketchbook with a thin piece of charcoal, copying the curving line of the Rokeby Venus from a coffee-table book on Velázquez. My mother stroked my father’s hair languidly, dreamily, as if they were underwater.

“We were just jumping on the trampoline,” I said.

She held a finger to her lips and pointed toward the front porch. Outside, my brother and my sister were crouched next to the steel trap. Emily was wrapped in her pink bathrobe, and Arnold was in his Hulk pajamas.

Herman and I knelt to have a look. The rat circled its cage, its tiny black eyes nervous. The way it moved, it seemed boneless. I had been right: there was something cute, almost kitten-like, about its face, especially the soft, pink, upside-down U of its mouth. Its mottled brown fur looked like an expensive coat, with a clean white underlayer, like goose down. It was pretty in the way that scary things can be pretty: I felt an urge to hold its weight in my hands, cradle it, and stroke it against my cheek. I was relieved that it had been caught, but I felt a twinge of loss, too.

“What happens to it now?” I asked.

“Animal Control will come tomorrow,” Emily said. “They’ll take him and gas him and burn the remains.”

My brother had dropped a few poison pellets into the cage, but the rat wasn’t eating them.

“It’s more scared of us than we are of it,” Herman said.

Emily nodded sadly at him. The rat stood on its hind legs and stuck its tiny nose through the bars. We all instinctively leaned away. It opened its mouth slightly, and its nose twitched and sniffed, catching the strange and dangerous scent of humans in the air.