In “Night of the Moose” William Giraldi and Sarah Braunstein recount a shared experience they had while driving through the Maine woods. They wrote their accounts without showing them to each other — there are minor discrepancies between the two versions — and then performed them at a reading series in New York City called “Double Take.” The essays have been edited for publication.

— Ed.

William Giraldi

On a humid night in July, my friend Sarah and I were discussing Denis Johnson’s story “Car Crash While Hitchhiking” in reverent tones as we drove down a lonesome road slashing through the Maine woods. We were coming from the University of Maine in Farmington, where we’d just spoken to an audience of students about reading and writing. I don’t know what lured us to the topic of Johnson’s story, in which a hitchhiker survives a car crash and ends up cradling a baby among the wreckage and the wounded passengers. Perhaps it was my persistent dread of car accidents, or maybe we were missing our small children — Sarah’s son, Asa; my sons, Ethan and Aiden. When you have young children with whom you’re defenselessly in love, any time away from them feels like time misspent.

Up ahead, held in our high beams, an enormous creature lumbered across the road. For the briefest instant I thought it was a Tyrannosaurus Rex. Isn’t it astonishing how, in the dark, in the woods, the quick sighting of something unexpected or incongruous fools the mind into mythical, fantastical explanations — a sasquatch, a monster? It wasn’t a T. Rex. It was a moose with a tremendous expanse of antlers.

At first Sarah and I didn’t see the car in the opposite lane because its headlamps had been smashed in by the moose. As we got nearer, we saw the woman dazed behind the detonated air bag, the two little girls in the backseat, the windshield in shards on the road. Our own headlamps provided the only light in the endless pine-scented black — not a house, not another car in sight. As soon as we stopped, insects swarmed, diving and circling in our beams.

The mother, who was in her mid-thirties, sat looking at her cellphone as if trying to recall its use. The two girls — blond like their mother, ages about ten and eight — whimpered but did not cry. Had they been wearing their seat belts? I thought of concussions, of hurt vertebrae. Sarah and I asked if anyone was injured and whether the woman had called the police; then we helped them from the car.

Inspecting the damage, I found moose hair wedged into the car’s grill, the hood compressed and bent upward so that the engine was visible. Fragments of debris crunched beneath my feet, and when I looked down, I saw that the older girl was standing without shoes on small cubes of glass, blood between her toes.

Sarah quickly embraced the younger girl, spoke to her in soothing tones. I lifted the barefoot ten-year-old and sat her on the trunk of the car. She didn’t wince or even seem to notice when I plucked the glass from her heels and staunched the blood with my T-shirt.

A pickup slowed, then stopped. The driver stretched across his front seat and asked out the window, “Everyone all right?”

“Yes,” I said. “I think so.”

“What happened?” he asked.

“It was a moose,” I said.

“Anyone call the police?” he asked.

“I don’t think so. Not yet.”

“I’ll call them,” he said. “I’ll tell them where you are.” And he drove on.

The mother was trying to dial her husband’s number, but her hands were trembling. Finally she made the call. I remember thinking it was miraculous that a cellphone could reach from this isolated place and snatch a signal.

“Whatever you do,” I told the woman, “don’t start by saying, We were in a wreck. Start by saying, Everyone’s OK, and then just say you hit a moose.”

When the husband picked up, she wailed, “We were in a wreck!” and I hollered into her phone, “Everyone is OK!”

Sarah again embraced the younger girl and explained to her that help was on the way, that there was nothing to fear, nothing at all. Seeing her with this child in her arms, in a ditch off some forgotten road in Maine, I felt in awe of her dignity, her humanity. If ever you want to know the essence of someone’s character, make sure to witness her with a child in trouble.

The mother was pacing, hysterical, and furious at the moose, which was akin to being furious at God. I’d stopped the bleeding from the older girl’s soles and had found her sandals in the backseat. As I slipped them onto her feet, she looked furtively into the woods. “I was so scared,” she said. “It was the biggest thing I’ve ever seen.”

“The moose is not coming back, sweetie,” I said. “He’s gone home now.”

“Is it dead?” she asked.

“No, I don’t think it’s dead,” I said. “It was just trying to get home, just like you.”

When I was small, my maternal grandparents had a cottage on a lake in Bridgton, Maine, perhaps an hour’s drive from where we were. Driving up from Jersey with my parents, I always knew when we were near, because the air became less polluted, more piney. Some of my most pleasant memories took place at that cottage and the surrounding lake and woods.

William Wordsworth speaks of the child’s “visionary hours” in nature, of those “vital feelings of delight” before the world clobbers him with the rituals and stipulations of being an adult. But that sun-strewn version of nature forgets to mention that, in the unwavering black of night, with the beasts and bugs and blood, nature is a horror.

We stood out there for thirty minutes before we finally saw a pulsing red hue coming over the crest in the road. I remember no sirens, only the silent spinning lights of the rescue truck. And then, although no storms had been in the forecast that day, an Old Testament rain cracked loose from the sky.

Sarah and I carried the children to the rescue truck. As we handed them off to men who knew what they were doing, Sarah said to the younger girl, “I’ll never forget you.”

Perhaps Sarah and I made only a negligible difference on the road that night, but it felt good to make it. We dashed back to my car, our clothes heavy with rain, my shirt marked with the blood of a young girl. In the quiet of the car it seemed as if we were about to weep, not for what had just happened — a smashed automobile, some lacerated feet, and a pair of frightened girls — but for what had almost happened, for our own children who are always so perilously close to ravaging our hearts.

Sarah Braunstein

It’s a blistering day in Franklin County, Maine. My friend Billy and I are driving to a university two hours north of Portland, to give a reading from our respective first novels to some high-school students — that strange breed that opts for writers’ camp at fifteen. We will read to them, encourage them, sell our books to them, and go home. We wend our way northward. Billy drives a big black SUV with black leather seats, a mobster’s car. I love this about Billy — his hulking vehicle, his confidence maneuvering it.

Despite the car’s air conditioning, the heat seeps in. There’s no relief from it, even on these roads shaded by trees.

Halfway there the road sidles up to a lake, and we stop for a break. We follow a path to the water and stand on someone else’s dock. We’re trespassing, but who would have the energy to press charges today? The lake shimmers like pennies. The air is scented with pine. We decide we’ll stop here again on the way back. It’ll be dark then. No one will be able to see us slip into the water.

Billy tells me his grandparents had a house in Maine when he was a boy. These are like the woods and the lake where he roamed and swam as a child. He gazes into the distance, the boy he was thirty years ago close to the surface. “It smelled just like this,” he says.

In an auditorium with broken air conditioning we read to the students. We sign books, stress the importance of reading, our moist hair plastered to our heads as if from the exertion of our commitment to literature. The sweetness of these pen-clutching high-schoolers moves us. Are we reminded of our own adolescence? More likely of our own children, barely out of toddlerhood, who will be teenagers in no time. No time. I imagine my son with his father in Portland, reading bedtime stories in front of a fan, and Billy’s wife, putting his boys to bed in Boston.

It’s dark when we leave, and hotter, as though a lid has been set down on the soup. The air is clotted with mosquitoes. I need to swim, need cool water on my skin.

The road is wedged into the forest like a needle stuck into a ball of yarn. There are no streetlamps here, no traffic lights. One of us, I can’t remember who, mentions the writer Denis Johnson, and we talk about his story “Car Crash While Hitchhiking.” Do we summon what happens next? Do we have that much power? We are sleepy and happy and hot, and these are the times one is tempted to believe that literature and life are the same, that the thin veil between them isn’t really there at all.

Our car climbs a hill, and as we descend, we see it: A dinosaur. A swaying beast, disappearing into the woods. There’s a car stopped on the other side of the road, its doors open. Did it stop to see the dinosaur? No. The dinosaur stopped the car. A woman stands in the road, waving her hands. We see two young girls in T-shirts and shorts but no shoes, standing together in sparkling shards of glass, screaming. Billy slams on the brakes.

The woman looks helplessly at the wreck. Another motorist, the only other car on the road, has stopped and is calling the police. The woman is too stunned to tend to her children, so Billy and I rush to them, our shoes crunching over broken glass. We each lift one into our arms and carry her to the far shoulder of the road. It’s unclear to what degree they’re injured. Their mother keeps repeating, “We hit a moose,” and, “I have to call my husband,” and, “I just replaced the fuel pump.” The girl I am holding, about six, is the bigger of the two. There is blood on her legs. Shattered glass sticks to her skin. Both girls are making glorious, devastating sounds, wailing as if to prove they haven’t died. Their mother is bemoaning the cost of the car’s fuel pump. The other motorist is suddenly gone, and now Billy and I preside alone over the accident. The child in my arms is hot and trembling. I smooth her hair. “We hit a moose!” she cries. “This is the most terrible thing that ever happened to me!”

I say, “Yes, you hit a moose. But you’re OK. Your sister is OK. Your mom is OK.” She doesn’t believe me, will not be calmed so readily. I respect her for this. I tell her my name. I tell her I have a boy just about her age. She sniffles and looks into my eyes. I ask her name.

“Maribeth,” she says.

Meanwhile Billy has metamorphosed into something of an army medic, moving through the jungle air with purpose, his face grave, his voice uncannily calm. (That boy I saw at the lake is gone.) Blood drips in thin, slow streams down the girls’ legs. He retrieves baby wipes from the glove compartment of his car — for he is a father, too — and cleans the cuts. When he pulls a quarter-sized hunk of glass from the back of Maribeth’s leg, she doesn’t seem to notice.

Maribeth keeps talking, her breath warm in my ear: “That was the scariest thing that ever happened to me. Did the moose live? Is he dead? . . . I was just playing my video game.” She looks at her hands, as if noticing for the first time that the video game isn’t there. She says, “I heard my mom scream, and I looked up and saw this thing — and fur — and I hate that moose.” She sobs again. “I want it to die,” she says righteously.

Somewhere in the woods the moose trembles.

The other girl, the littler one, is whimpering. The mother hears Maribeth saying how scary it was. “Scary for you?” the mother says, dumb with awe. “You should have seen it from the front seat!”

While she and Billy discuss the state of the car and the details of automobile insurance, Maribeth whispers in my ear, “That was the scariest thing.”

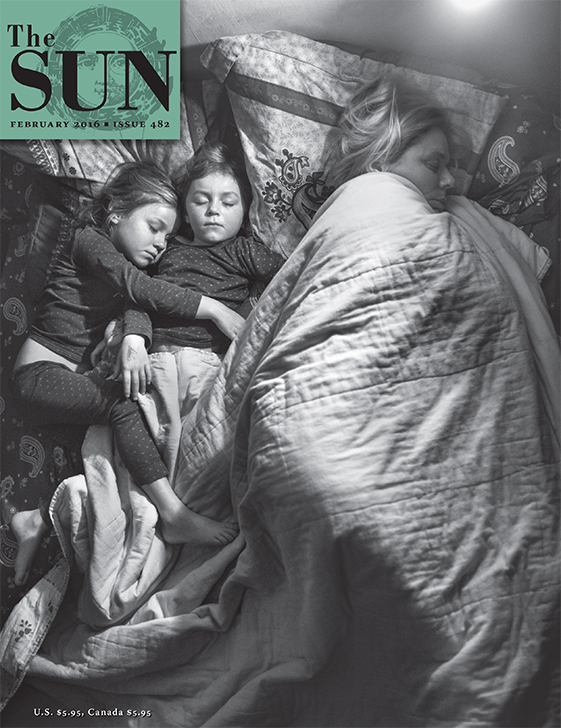

“Tell me,” I say. She does, again. I stroke her hair, pull out a sliver of glass. She weeps, but more quietly. “I think I want to sleep with my mama tonight,” she says.

“Is the car totaled?” the mother asks, the other girl clinging to her leg. In his army-medic voice, his dad voice, Billy assures the woman that the car doesn’t matter.

“You’re a brave girl,” I tell Maribeth. “You’re safe, and you’re brave.”

“I’m brave?”

“Very brave,” I say.

I think of my own son — I can’t help it — on the side of a road like this. His hair. Glass. Get him off the road. Don’t put him there. He doesn’t belong in this story.

I hold the girl until the ambulance arrives, its lights flashing. Then — rain. The most outrageous rain, biblical, pitiless, slapping our scalps, needling our eyelids, drenching us in an instant. I take my girl, Billy takes his, and we run to the ambulance. The doors open. The mom climbs in. We can’t hear anything over the downpour. Before I hand Maribeth over to an EMT and leave her to the whims of the world, I whisper into her ear that I will not forget her. I don’t know if she hears me. There is no time for a response. The doors slam shut, and the ambulance speeds off.

Billy and I run back to his car. In our haste we forgot to shut the doors. The interior light is on, and the car is full of bugs. We get in; Billy turns off the headlights. The rain hammers the windshield. We don’t speak. We just sit on that pitch-dark road, dripping water onto the leather upholstery, bugs on our arms and legs, and say nothing for a long time.