“Do nothing. Time is too precious to waste,” said Buddha. If that sounds like nonsense, then read on as I tell you how I and my wife, Janet, came to do nothing with our farm, on purpose. It might help you understand what Buddha had in mind.

Twenty-eight years ago, after six years of living in Manhattan, Janet and I bought 134 acres of farmland in rural New York State — midway between Ithaca, where I’d gone to school, and Cooperstown, home of the Baseball Hall of Fame — and began going there on weekends and in the summer. The land was in Chenango County, in the southeast corner of the Burned-Over District, an area which, in the nineteenth century, produced the Mormons, the Perfectionists, the Millerites, the Anti-Masonic Party, and a host of other quirky individualist movements that attest to how rich life can be in a less structured society. Chenango County was, is, and I think always will be lightly populated, a land of corn and livestock, not appealing to sophisticated tourists and real-estate speculators.

The population of the town nearest my farm is the same now as it was in 1905; the whole county has about fifty inhabitants per square mile — less than it had in 1835, during the glory days of the Chenango Canal. Even in 1993, plenty of beautiful land was available there for five hundred dollars an acre or less, ninety minutes from Syracuse, two hours from Albany, four hours from New York City. I paid only about forty-eight dollars an acre in 1968. The low price was probably the chief reason I bought the land sight unseen from an ad in the real-estate listings of the Sunday New York Times.

That particular Sunday I had been ranting and raving to some friends about the great bargains that are always available, if you know what true value is. I offered to prove my point using the real-estate pages. “Just buy what no one else wants,” I said, “as long as you’re sure that their reasons for not wanting it — dirt roads, no running water, things like that — are dumb.” Then I read:

Tumbling Waterfall Retreat

134 acres. 7-year mortgage. 6%. Old barn, pond sites. 5 miles from Oxford, New York. $6,500.

I wired the five-hundred-dollar down payment to the agent the next day.

How did I know the land was any good? Maybe it wasn’t good for some things — such as making money. But I knew it was a private place away from modern machinery, where I could do just about anything I wanted without interference and nosy neighbors, so I bought it without worrying. If you know your own mind, you don’t often require expert advice to make decisions, because you are the only real expert on what you need. With the payments around a hundred dollars a month, almost anyone could have bought that land, if he or she wasn’t afraid.

What was there to be afraid of, after all? The taxes were about three hundred dollars a year, and a nearby farmer paid us a hundred dollars annually to cut off the grass for hay — paid us for the privilege of cutting our grass.

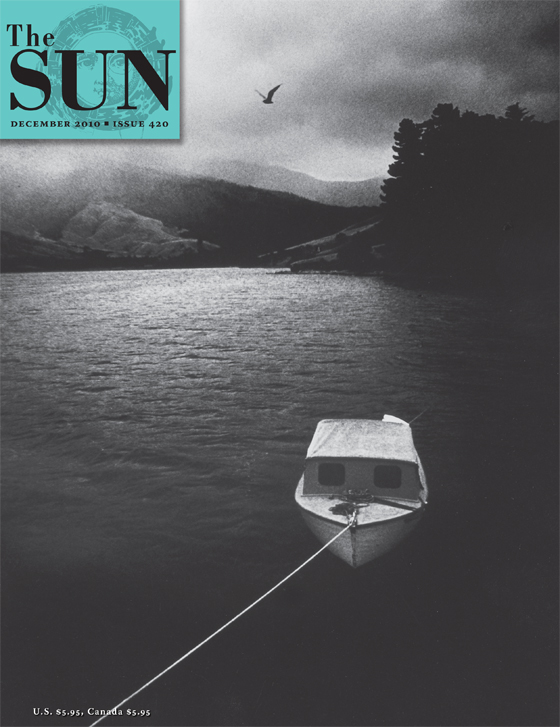

Wild land puts us smack in the middle of animal nature, where creatures regulate their lives differently than we do ours. It teaches us about seasons, fertility, and that there is no death, just endless transitions from one form to another. Wild land gives us back the sky and the harmonies of the planet, and exacts only a small price in return: we must leave it wild, or else it loses its power and becomes a green office.

By the time I bought my wild land, I was thirty-two and just beginning to see that doing things the “right” way — rationing my time using the best principles of human engineering, living life according to my mind rather than my heart — was a catastrophic mistake. I had already mutilated my family with too many rational decisions. But I was slowly starting to realize that you can’t engineer life all the way unless you’re willing to become a mechanism, that all the rewards that can be counted — like money and titles and honors and property requiring expert advice to manage — are at their roots disturbingly unrewarding. I hadn’t always thought that way; I had gone to two Ivy League colleges specifically to accumulate material wealth and display it as evidence of my worth. And I did that for a while, but, ironically, it left me feeling worthless.

When I bought the land, I still hadn’t learned this lesson I’m trying to teach you — or rather that Buddha is trying to teach us both. For five years I raced around digging ponds, chopping trees, clearing paths, pulling rocks, unclogging channels, planting — always making lists, plans, agendas; always “improving” things. I loved to drive to the nearby towns and see movies and sit in bars pretending to be a country gentleman, but Janet would regularly ask why we couldn’t just stay put, why we always had to be going and doing. Her question baffled and intrigued me: stay put and do . . . what?

One day, after finishing yet another important project, I made a list of all the things I had left to do according to my master plan for the land. There were fifty major projects remaining, and at two a year (which was all I could manage while racing back and forth from New York City on weekends and in the summer) I would be sixty when they were done. According to my schedule, I could begin enjoying my land twenty-five years down the line.

Something was dreadfully wrong. I was a fool. Like so many of us, I was a cog in an idea-machine called “progress.” I measured success like an accountant: by the bottom line of things done, gotten out of the way, finished, terminated. But the pleasure of being alive lies in the process, not the product — primarily in being and only peripherally in doing. Our envy of machines has reversed this natural order of importance; somewhere deep down we all understand this, but we avoid the truth and instead assign ourselves the miserable task of trying to be machines. Regardless of appearances to the contrary, those who succeed at this lead horrible lives.

Being a part of the natural world is the great challenge — without accepting it, we can never have a true home. Nature stops giving when it is overregulated, or exploited with technology and bulldozers. We all need wild spaces to restore our spirits, not just parks and beaches, where the human element is all too apparent. When we dominate the wilderness by mapping it, scheduling it, and controlling it, all we get is a green version of the city.

Now I do nothing with my farm but go there and let it teach me things. Sometimes I putter, but not often, because “time is too precious to waste.” The living quarters are an old barn with “1906” inscribed in the concrete milking floor. I had originally intended to build a broad covered porch around the structure and turn the inside, with its fifty-foot ceiling, into a private cathedral. Not a bad idea. But now, twenty-seven years later, it remains a barn, and that has turned out to be a better idea. There’s about twelve hundred square feet of open space on the hay floor, and way up under the roof is an insulated room reached by climbing three wooden ladders. The boyfriend of one of my college students built the room, put on a new roof, and refloored the barn in exchange for five acres of land: a good deal all around.

But much of the time we don’t even use the new room; instead we sleep in two lovely old beds under the lofty roof, with a few mice racing about the rafters in plain view, bats squeaking in the eaves, barn swallows twittering. In the morning, the most amazing light pours through the inch-wide gaps between the vertical wall boards. It’s like living in a birdhouse.

We draw water a half-mile away from a gorge that probably should have been tested but never was; we drank tentatively at first, then with delight. No water ever tasted like our gorge water run over rocks. Although the walk back and forth took some getting used to (it was hard to escape the machinelike notion that time was somehow being wasted), I’ve found that drawing my own drinking water is a wonderful feeling.

Bathing is out of a bucket or in ponds, and the toilet is wherever you can find a private spot. Our place on the Upper West Side has three bathrooms, but they give us no better results.

Our barn holds about three thousand books, which must fend for themselves in all seasons. We bought them at country auctions for a dollar or two a box — lots of nineteenth-century evangelical tracts, hand-colored children’s books, crime-club thrillers, and the like. They’re entertaining far beyond television, movies, and Broadway shows. Reading in a barn is like discovering reading all over again.

The main activity on our farm, as on many farms, is keeping animals; the difference is we don’t own any of them, and they feed themselves. Deer are a daily sight — snorting, playing like young pups, hanging out. Wild turkeys are common, too; at night they flock by the gorge behind the barn. Plenty of snakes about, but no one has ever been bitten; also skunks, turtles, raccoons, coyotes, foxes, minks, and a large colony of blue herons, which land on the pond and fish like pterodactyls off our half-sunken dock. A bear moved in near the stream at the foot of the hill last year. Our relationship is strictly live and let live; it’s nice to have a bear around. The most unbelievable creatures of all are the moths. Janet discovered them flying just outside the barn at twilight; their shapes and colors are so exotic, I feel transported into prehistory just watching them.

Of course, we do other things, too: We eat wild foods we used to call “weeds.” We dig up blueberry bushes for gifts, build bonfires at night, transplant wildflowers. I finally figured out why real farms are often messy looking: when you kick over something unimportant, it doesn’t need to be picked up right away, and nothing should ever be thrown out that might be useful tomorrow.

It’s impossible to live this way for long without coming to love nature, and to feel an obligation toward it as well. Our natural laboratory is stretched out daily for our understanding, not our exploitation. The greatest use of wild places is not “using” them but just being there.

I wish I had been brought up to live in productive harmony with the land, but I’m grateful to have discovered the next best thing: accepting stewardship of it until someone better suited to live upon it self-sufficiently comes along.

When I used to teach school, my students and I would discuss style a lot — particularly, how to get a style of your own. It’s very difficult unless you are alone a lot, have time and space to yourself, are free of other people’s needs and the urgencies of the commercial world. How can you expect to be unique if every minute you draw models from other people and from the televised shadows of real people? How can your unique destiny unfold if you always submit to the scrutiny and judgment of authorities? (Authorities on what? Certainly not on you, unless you have been diminished into something predictable, tamed by regulation, simplification, and rationalization.)

We are meant to be unique individuals who live in harmony with other unique individuals: think of the harmony of falling snow, but the brilliant individuality of each snowflake; the harmony of beach sand, but the uniqueness of each grain. Aren’t we that way, too? Consider your own fingerprint, unlike any other on earth — why would evolution produce such a mark unless each organism is one of a kind? And if you’re inclined to think in terms of God, rather than evolution, it is even easier to deduce a purpose. If people are inherently sortable into a few categories — as industrial civilization makes us out to be — then the fingerprint is inexplicable; it only makes sense as a guide to the individual experiment that is each one of us.

As Buddha said, time is too precious to waste doing much of anything. I’m still learning what that means, but I might never have begun to learn if I hadn’t bought a big piece of wild farmland and left it that way. (I hope my children’s children leave it that way, too, if circumstances allow them to inherit it.) I learned to just be from watching fish swimming in the pond, birds taking dust baths on the dirt road. “Hey, look at us,” Janet once said. “We’re just watching the birds, not ‘bird-watching.’ ” It’s an important distinction.

The original meaning of the word school (in Latin, schola) was a place that afforded solitude, silence, and freedom from duties so students would have maximum opportunity to open themselves to the universe and learn. It’s difficult to find such a school. Our institutions are too occupied with watching us for signs of unacceptable deviation, and regulating each minute of the year according to expert prescriptions.

Wild, inaccessible, unimproved land is available in abundance within easy drive of every metropolitan area in America. Get some as soon as you can — the wilder and scruffier, the better. Then do nothing. It will be your school. And it might become your home.