I remember clearly how it started. I was fifteen years old. It was the middle of winter, the house hazy and yellowish with dry furnace heat. I had eaten a Lean Cuisine lasagna dinner — a dish that had fewer than four hundred calories (good for me) and required no preparation (good for my mother) — and gone upstairs to my room to finish my homework.

As I sat cross-legged on my saggy twin bed, my books in front of me, I became aware of a strange spasm in my stomach: the muscles squeezing themselves into a tight fist and then opening again. I tried to keep working, but the squeezing drew my focus inward: What is this? I wondered.

I walked down the hall to the bathroom, knowing somehow that I would throw up. I knew not through reason or from experience — nothing like this had ever happened before, and I didn’t feel the slightest bit nauseated — but through some other faculty: a primordial instinct, a dark intuition.

The phone rang. It was one of my classmates with a question about the trigonometry homework.

“I can’t talk to you right now,” I told him, slightly giddy. “I guess I’m throwing up my dinner.”

Afterwards, I stepped into numbness, a blurring of edges, like a world observed without glasses. It was smooth, and I welcomed it. What is this? I wondered still — curious, but unperturbed. And then I went back to my homework.

The next morning, as I was brushing my teeth after breakfast, it happened again. My mother clucked her tongue and sent me straight to bed. Though she fed me sick foods exclusively — toast with jam, orange Jell-O, chicken broth — everything that went down came back up. In between meals, I did the New York Times crossword puzzle, I read, I watched television. At night I slept like a stone.

Since I didn’t actually feel ill, I returned to school after a few days. In public, I took pains to keep my condition — whatever it was — under wraps. I didn’t want to be caught throwing up in the bathroom at school and decided that I just wouldn’t eat while I was there. If a classmate or teacher expressed interest or concern, I offered polite but vague explanations.

At home, things were different. My parents and I became quickly desensitized to this new behavior, and I threw up in front of them without guilt or embarrassment. I threw up right at the dinner table, into whatever happened to be handy — a soup bowl, a drinking glass — and the three of us picked up the conversation where we’d left off. I vomited ice cream into the dish I had eaten it from and continued watching television in the den.

My brother, home from college one weekend, stepped into my room and then immediately shrank back, as though he had been hit. I was doing homework, with a drinking glass half full of regurgitated lunch on the corner of my desk. It had become my habit to wait until the glass had filled up completely before emptying it into the toilet down the hall.

“That’s disgusting!” my brother said. Shame flared up inside me. For a moment, I stepped outside of this liquid world that my mother, my father, and I had been inhabiting. Then, just as quickly, I dissolved back into it.

My parents’ supreme comfort with my symptom strikes me now as wholly abnormal — acceptance gone too far, crossing the line into oblivion. I don’t mean to suggest that they didn’t care. My illness worried them deeply. They took me to the best specialists without concern for cost. They called anyone they could think of who might have some idea why their otherwise healthy daughter could not keep her food down. “We’ll get to the bottom of this,” my father said. “I promise you, we will.” And in the middle of the night, I often heard one or the other of them creeping around, kept awake by worry.

But as much as they wanted to “get to the bottom of this,” they also preferred not to dig too deep. And so did I. We had always been skilled at ignoring the obvious: for example, that my parents’ marriage was on the verge of collapse, should have collapsed long ago except that they believed in sticking it out, no matter how miserable it made them. I had watched the way each of them pulled in and stiffened when touched by the other, the way they kept their distance, turning away from each other at night, their twin beds pushed together but made with separate sheets. But while I could conjure these images, I could not let them add up to a conclusion.

My mother had been depressed for years, prone to crying jags, incapable, for weeks at a time, of changing out of her bathrobe, barely able to cook a meal. She needed quiet and shadows to soothe her migraines, a gentle massage every Friday afternoon to loosen the kinks in her muscles. She needed medicine, each new pill holding new promise.

I was one of those pills, miserable and depressed, too — wanting to relieve her, afraid of being swallowed. The remedy I promised: a second chance at perfection, the possibility of redemption, after my older brother had turned out a mystery, a cluster of complications and dilemmas and unbending will.

My father, too, was unhappy. I sat with him at the breakfast table one day while he talked, shaking his head and gazing absent-mindedly at the wall. “I hardly need to speak and you understand,” he said. “Mom and I just don’t have that.” His grief weighed me down, the telling of it even more so.

I had soaked up what was around me — every reaction, every facial expression, every emotional nuance. It was too much. Now here I was announcing my saturation, bursting forth onto the scene in a rush of vivid color. Foul-smelling pieces of me lay all around the house but did not fully capture our attention. Ultimately, chatting at the dinner table with a bowl of vomit in plain view was not a reflection of my parents’ love and tolerance. It was proof of our family’s blindness.

I went to doctors. First I saw my pediatrician, Dr. Goldman, a lanky man with thick glasses that made his green eyes bulge like grapes ready for picking. He weighed me, peered inside my ear canals, shined a light down my throat, palpated my intestines with his tapered, porcelain fingers.

“Are you working hard in school?” he asked.

I looked at the floor, a smoky white linoleum tile flecked with green, and answered, “No more than usual.”

“Do you feel you’re under a lot of stress?”

“No more than usual.”

Dr. Goldman thought I might have an ulcer. The word made me think of a glowing red blister, the color of an exit sign, nesting in a fold in my stomach. He referred me to a gastroenterologist, who doped me up and slid a wire down my esophagus while I laughed and dreamed of bright triangles.

There was no ulcer. The gastroenterologist thought there was something he might be overlooking and referred me to a colleague for an upper GI. I drank an endless volume of barium from a plastic cup and then lay on a padded table that swung up, down, and sideways while a machine took pictures of the pink, sluggish liquid meandering through my insides. I saw a proctologist, an endocrinologist, a gynecologist. Stumped, each one passed me along to the next in line.

When the doctor who had treated me for viral meningitis in Israel the summer before came to the States for a visit, my parents invited him over for Sunday brunch — in part as a way of thanking him for the care he had given me, but mostly so he could observe me in action.

My father made a pitcher of Bloody Marys and cooked omelettes, each one perfectly formed, a dollop of sour cream beaded with salmon-roe caviar at its center. My mother baked banana bread. We chatted pleasantly while we ate, and then the conversation grew awkward, a way of passing the time while we waited, all of us, for me to begin throwing up. I danced my hand across my stomach, the pads of my fingertips listening for the familiar wave of tension and then release, but my stomach remained uncharacteristically still. We settled into the living room and waited some more. I showed Dr. Feldman pictures from my trip that summer, captioning each one as I passed it over to him. All I could think about, though, was how much thinner I looked in these pictures — and how my stomach, right now, wasn’t behaving according to expectation.

Dr. Feldman stepped outside for a cigarette. Come on, I said to myself, feeling panicky. This has to happen! I drank glass after glass of apple juice until it did. I threw up into the kitchen sink while Dr. Feldman and my parents stood in the doorway, watching.

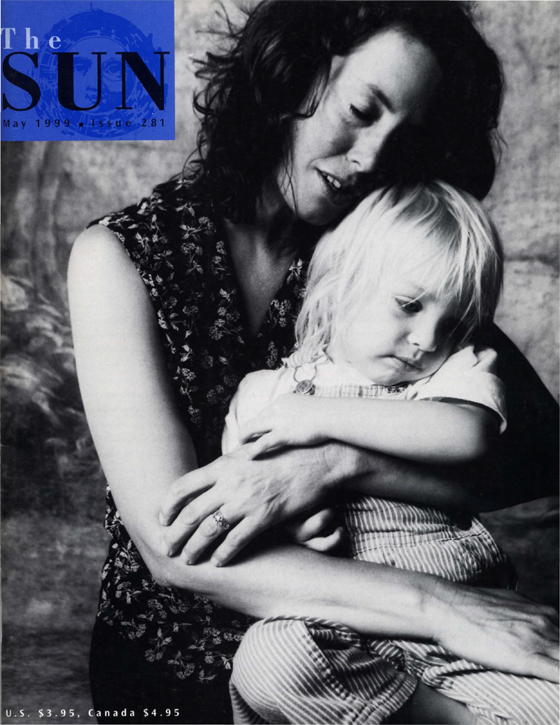

I had a history of helping illnesses along. From early childhood on, I’d always enjoyed being sick, because then my mother touched me. I came home from school at the end of the day, eyes bright with fever, and she slipped my pajamas over my head, tucked me into bed, and sat with me quietly until the sun set, brushing the sweat-soaked bangs off my forehead. Emotional distress, according to her, was not generally reason enough to cry, but it was OK to weep from physical discomfort. And so I did, thankful for the sharp knife of pain slicing through my ear, the electrified web of cramps in my abdomen, the driving pulse of swollen glands. Every symptom was a spell my body could cast: She will give you what you need; just ask. And I did ask, and every request was honored. A glass of orange juice, please. . . . Can you make the TV louder? . . . Mom, I have to go to the bathroom. She would help me down the hall, whispering encouragement while the floor swerved below me, wincing along with me as my feverish skin touched the cold porcelain seat. The attention made her beautiful.

I clung to my sickness tenaciously, doing what I could to prolong that connection. I had bronchitis three times in fourth grade; each bout kept me out of school for three weeks. I had been told to try to suppress my cough, but I chose not to swallow the tickle deep in my chest; instead, I gave in to it, savoring the gummy rattle of phlegm, the faint taste of blood seeping upward onto my tongue.

Here I was again, tampering with my body until it cooperated — in part, I realize now, because I still wanted the light sweep of my mother’s hand across my forehead, though I had outgrown my bangs years earlier and her hands looked older now, the green veins pushing harder, rising like mountain ranges on the topography of her skin. It was all she and I had — a shared landscape of disease, the only place we could find each other. And there, she could rise out of her bed and work on instinct. My discomfort gave her life.

Yet on that Sunday morning, as I gulped down apple juice because I knew it would help me throw up, it still seemed to me that the impulse originated in my stomach, not in my head. If anyone had asked me whether I was making myself vomit, I would have said no; that was how I understood things at the time.

My parents . . . called anyone they could think of who might have some idea why their otherwise healthy daughter could not keep her food down. “We’ll get to the bottom of this,” my father said. “I promise you, we will.” . . . But as much as they wanted to “get to the bottom of this,” they also preferred not to dig too deep. And so did I.

Four weeks after that first night, the chain of New York City specialists looped back to Dr. Goldman. He weighed me again. The scale balanced at ninety-five; I had lost ten pounds.

“Do you realize you’ve lost a lot of weight?” he asked.

I nodded. I had noticed the way my pants hung lower on my waist and bunched out more in the seat. When I lay on my back, my hips stuck out like two halves of a broken saucer. I’d never been overweight, but I had gone on my first diet a year earlier, and since then had always been either gaining or losing weight. This was the skinniest I’d ever been, and I liked the way it felt — how tiny and taut my body was, lost inside my clothes.

“Are you trying to lose weight?”

“No,” I said, though it pleased me to know that very little of what I was eating was being absorbed into my system and turned into flesh. My head had lately been cluttered with calculations: I counted calories at each meal and then estimated how many of those calories had stayed with me — were not thrown up. I returned to these numbers over the course of the day the way some women play with their earrings — a distracting comfort, a nervous habit. Had I calculated correctly? Was it all still there? Where was I, calorie-wise, at this point yesterday? When I closed my eyes at night, I saw columns of deep purple figures, pulsing and then fading out.

“Does that mean you’re happy with your weight?”

“Well, sort of,” I said irritably. “I mean, I wouldn’t mind if I lost a few more pounds, but I’m not actually trying to.”

“I don’t think this is a physiological problem,” Dr. Goldman said. “There’s a psychiatrist I know; I’d like you to see her.” He patted me on the shoulder, but I pulled away, stung by his betrayal.

Dr. Harding’s Park Avenue office was enormous, all light and air, with a ceiling so high it seemed to be floating away. The sun beamed misshapen squares of light onto the vast Oriental rug. Her narrow beige armchair sat at one corner of the rug, positioned like a gymnast preparing for a tumbling pass — as far back as possible without going out of bounds. Dr. Harding was old but well-preserved, with silver hair teased out in loose waves around her head. She held her back perfectly straight as she took notes on a yellow legal pad.

Through the window behind her head I could see bits of debris — a jagged swatch of corrugated cardboard, a plastic take-out lid — circling in tight eddies and then flying off their orbits out of view. It was deceptive, how the sky could be so thick with the rich silky blue of an oil paint, how the sun could shine as if it were melting rooftops — while the wind whipped so fiercely and the air turned everything brittle.

She asked me ordinary questions. But with her icy, blue-dot eyes roving my face like penlights, they seemed pointed, hurtful, and I didn’t want to answer them.

“Do you enjoy school?”

“Yes,” I said, shrugging my shoulders. It was a lie, mostly. Sometimes my studies engaged me, but I worked too hard, worried too much, spent too little time goofing off.

“So then you have some good friends, yes?”

“Well, yeah.” Another lie. I had a few friends, but there was no one to whom I felt truly close. I often remarked mournfully in my journal that my cat was my best friend — my handwriting neat, full of self-pity, each letter a small, cowering animal.

“Do you get along OK with your parents?”

All I could do was shrug; I knew if I opened my mouth to speak I would cry. I bit down hard on my lip and focused on the single point of warm, sharp soreness.

“Are you happy?”

A voice barely attached to me said yes.

“Well,” said Dr. Harding, flipping through the pages of her legal pad and then hanging her eyes on me like hooks, “you don’t look happy to me.”

I left the gleaming brightness of her office and refused to see her again. “That woman is such a bitch!” I told my parents. “I’m never going back there.” In their misguided desire to protect me from pain, they obliged.

A few days after I saw Dr. Harding, the vomiting abruptly stopped. She had scared me straight, frightened my stomach into playing dead.

The world tilted quickly then, without explanation. After weeks of eating very little, and throwing up much of what I did eat, I suddenly began to eat without stopping. I told myself it was a medical imperative: according to Dr. Goldman, my weight was ten pounds shy of normal. But my eating — bingeing, I should call it — had nothing to do with following doctor’s orders. Perhaps it was a matter of self-preservation: my body had dwindled down to a critical mass that tripped off the alarms, and was now scrambling to right itself. Perhaps all those weeks of denial had finally caught up with me, a kind of appetite accrual, and all I was doing was making up for lost time. Maybe, on the other hand, it wasn’t a response to self-abuse, but another manifestation of that same impulse, a new way of doing the same old body damage.

It took no time for me to gain the required ten pounds, and still I ate. And then, for another two years, I fell back into the old cycle — diet, gain weight, diet again — as familiar, as heartbreaking, as the seasons.

My Latin teacher gave his students this advice: The only way to learn these declensions is by writing them down. You have to copy them over and over and over — he would strike the desk with each over for emphasis — until your hand is sore. The fingers learn. They will remember.

So it was with me and my stomach; patterns had been etched into pink tissue. And then, in my freshman year of college, I discovered my body’s secret: I could throw up if I felt like it. The organ remembered and instructed me. All I had to do was tense up my stomach muscles and then release, tense and release, and wait. And it would happen.

And then a second thing, more like learning a tennis stroke. At first, your body moves in discrete segments, each one a separate marshaling of thought and action: pivot, reach, swing, and follow through. But soon enough, the edges bleed. You start to feel as though you couldn’t have the pivot without the reach, the swing without the follow-through, so linked are these movements by repetition. You stop thinking of parts; you think of a larger whole, one fluid movement. And you have yourself a forehand.

So it was, again, with me and my stomach: First, I had mastered the binge. Later, I had learned to throw up on purpose. Now I put the two separate actions side by side, and they connected, integral pieces of the same behavioral puzzle. The more I ate, the easier it was to throw up; and the more I ate, the more I wanted to throw up. The purge never came as an afterthought. I binged with the purge in mind, could not conceive of the first without the second. The purge completed the action, closed the circle. It was follow-through. A perfect stroke.

I was assigned a single room in a suite with five other women. The day I arrived, in a burst of optimism, I donated my new stereo to the common room: we’d all hang out together! But I spent no time there; none of us did. My suite-mates made friends, played in the orchestra, joined intramural volleyball, tutored inner-city high-school students. I retreated into my room, where I studied and wrote in my journal.

At night, I binged and purged in secret, my illness at long last coming into its own.

The purge never came as an afterthought. I binged with the purge in mind, could not conceive of the first without the second. The purge completed the action, closed the circle.

Each episode was a panicky whorl punctuated by quickly calculated, staccato steps — Do this, quick! Now do this, and this! Each step was a spark bringing me closer. To what? I couldn’ t have said. And that muteness strikes me as one of the most bizarre features of my illness.

We are always telling ourselves stories to articulate why we do things. The logic, of course, might be completely false. People with compulsive disorders are particularly adept at constructing twisted rationales. An anorexic might tell herself, “If only I could lose a few more pounds, life would be OK. So I’m going to stop eating lunch.” An obsessive-compulsive might tell herself, “I’m not 100 percent sure that I locked the front door, so I’m going to check it one more time, and then I’ll be on my way.” The story is inaccurate, a surface justification for an infinitely more complex set of behaviors; but still, there is an explanation — one that satisfies her as she turns on her heels and heads back up the walkway to jiggle the brass doorknob for the tenth time that morning.

But for me, there were no reasons. I never told myself a story. Something — an impulse, a nebulous but distinct need — simply kicked in and took over, funneling the course of my evening toward that single purpose. It was a force that operated outside of cognition, precluding words and thought, precluding even the need for words and thought.

I suppose this muteness makes a certain amount of sense. I was incapable of constructing a cohesive picture of myself as a human being with a complex, nuanced identity. And if I was fragmented self from self, why not mind from body, too? Perhaps it shouldn’t surprise me that my body’s activities were of little interest to the part of my brain that sought and constructed explanations. Perhaps, too, my body was speaking for me, articulating through behavior the hidden, damaged parts of me that language could not reach, could not repair, could not bring to light. Perhaps this wordless state was one of the gifts my binges and purges gave me: the divorce from the verbal, thinking self; the eclipsing of thought through mindless action; a retreat into numbed-out relief, into silence.

Here’s how it was:

You are headed home from the library, but first you stop at the campus candy shop: candy sold by the pound, dispensed from clear plastic chutes lined up like organ pipes against the wall. Wait in line, casual, casual. Order half a pound of peanut M&M’s. Slip the package into your bag — because you want your hands free, not because you have something to hide. Pretend you are buying provisions for a study date. Check your watch; you want to be on time.

You leave and suddenly turn left instead of right, walking away from campus, weaving in between packs of swaggering boys, loud with drunkenness. Two seedy blocks and you’re at Store 24. The red linoleum floor stretches out in front of you. You stop in front of the Pop Tarts. Wait! Isn’t that a guy from your French class coming in? Keep going, keep going, thumb through magazines until he leaves. OK. A box of Pop Tarts. Any flavor will do, but they have to be frosted. Frosted Pop Tarts make you sick sooner; they come up more easily. Pretend you have a bad habit of sleeping till eleven, and you are buying these for the days when you miss breakfast. All completely aboveboard. Zip the box into your knapsack. Careful not to let the bag of M&M’s show.

You are breathless, your chest braided with fear and excitement. One last stop: Wawa, for a pint of chocolate-chip ice cream. And that’s it, you have what you need, you’re supplied. But wait — maybe a Snickers bar for the walk home? Pretend the Snickers bar is a snack and the ice cream is for some other night, a treat to be shared among friends. Pretend you are going to open the minifridge the moment you get home. Pretend you will slide this pint of ice cream onto the freezer shelf, watching the edge of the container scrape the carpet of frost on its way in, and then you will shut the refrigerator door and forget about it.

Next to the freezer at Wawa, there’s a door with a smudged square mirror on it. You suspect it is a one-way mirror, installed by management for security purposes. You catch sight of yourself but try to see past your reflection, looking for a grease-ball store manager in a short-sleeved dress shirt, squinting back at you through cigarette smoke. But your mirror image refuses to dissolve. There is a girl staring back. Her cheeks are swollen, her nose delicately etched with broken capillaries. She carries a knapsack loaded up with junk food. This is you.

Back in your dorm room, you shut the door and lay out your goods on your desk. You cannot wait. You peel off your jacket between handfuls of M&M’s and toss it on the floor. You dig into the ice cream with a spoon you lifted from the dining hall. You tear open the Pop Tarts and bite into them two at a time. You get creative with your food, mashing the M&M’s into the ice cream and then sandwiching the mixture between two Pop Tarts. Finishing is all you think about, this food is all you see, this task is all you are. You eat without pause until every bite is gone.

The purge is in part damage control: you will not accept all those calories; you could gain two pounds tonight alone. In part, too, it offers you physical relief. You have eaten so much you are in great pain; your stomach seems to have expanded in all directions — even upward, leaning against your lungs. But you also have a sense that you are completing what you’ve begun; the purge is not only a response, but a conclusion. You cannot get all of this without also giving it up. There is, of course, much more going on. You are doing other things to your body, yourself, when you binge; you are rejecting more than just these calories when you purge. But the metaphors don’t occur to you right now. Right now all you know is that you must throw up.

If no one’s around, you use the toilet, but most nights someone is home, so you make do, throwing up into the packages the food came in. You have to work quickly and carefully, because the vomit softens the cardboard, and the containers leak. When you have thrown up as much as possible and the cartons are dangerously full, you put everything into a double-bagged plastic bag, tie it tight, and then drop it in the dumpster behind your dorm. Done.

I never told myself, “I don’t have a problem,” or, “I can stop this whenever I want.” I knew it was a problem. I also knew I had no control over it.

For a while, in the beginning, I woke up every morning and thought, What happened last night will not happen today. Feel how peacefully your heart beats, curled up like a sleeping puppy in your rib cage. Look at that thin streak of cloud trailing across the pale sky. Notice the majesty of this building, your dorm, these elegant stones chiseled to a thousand subtle facets. With all these things, you will not need to — But soon enough my heart would flinch, the sky would darken, and when I returned from class the façade of my dorm would lean in on me, each stone purple as a bruise. And so, though I never stopped wishing I could rid myself of this behavior, I stopped believing I had the power to do so.

The battle for me was not between denial and truth, but between what I felt and what I knew. Each time I tried to head off a purge by reasoning with myself — It’s better to gain a little weight than it is to throw up and stay skinny — a louder voice, coming from deeper inside of me, responded: No, it’s better to throw up. You have to finish what you started. And no matter how much I tried to dismantle it, there was a hierarchy of eating disorders rooted firmly in my head: at the highest point hovered a see-through, anorexic angel; below her, a row of bulimics stood at attention like sentinels guarding the throne; and below them — below us — swarmed a legion of overeaters, commoners. I asked myself, Why this messy, swirling disorder? Why not, instead, the clean, calm lines of anorexia, all hollowed-out elegance?

One of my suite-mates, Amy, had started the school year running every morning during breakfast. A few weeks into the semester, she began to run in the evenings as well. She stocked the minifridge with Diet Cokes and McIntosh apples and started skipping lunch and dinner.

Amy was tall, with chin-length blond hair and smooth skin. She was chipper, enthusiastic, a series of exclamation marks. When someone asked how she was doing, she said, “I’m doing great! How’re you?” Her gray eyes were scrubbed out, empty.

Amy’s shoulder blades began to jut out beneath her shirt; between them, her vertebrae stretched down like a string of pearls. Charlie, her high-school sweetheart, took the train down from Harvard to visit her on weekends. He seemed not to notice that Amy’s angles were sharpening. I imagined him spreading her out on the bed at night like an outfit he might wear the next day, shuffling femur and forearm and rib cage until he had it just right — and then penetrating her from above.

Amy talked on the phone in muffled, tearful tones late into the night. I knew she was sick, unhappy, no better off than I. But I coveted her vacancy, her bones.

I started therapy. It had occurred to me by then that I was profoundly unhappy. It was a new and terrifying awareness, and these sessions sustained me. My eyes blinked, adjusted to darkness, and began to make out the shapes of my despair. There was so much more than just the single symptom that had sent me, scared and bewildered, to my therapist’s office: my shameful secret, my bulimia.

Bulimia. I had seen the word in print many times before and knew that it described my eating disorder. But I had never actually uttered it. I could not even bring myself to write the word in my journal. Instead, I wrote “b.,” as in, “Today we spent the entire time talking about b.” Maybe the whole word was too much to handle at first; I needed to learn it piece by piece, slowly.

Now here was this woman saying the word right to my face, animating it, inserting it into my life. She pronounced it byoo-limia, like beautiful. The first time I tried to say the word back to her, it got stuck sideways in my mouth. I practiced it in bed that night, staring at the street light outside my window. I whispered the word to myself over and over, until it spilled easily off my tongue. Over and over, until it meant nothing.

I did not return to school the following September. Instead, I stayed in New York, in a Park Avenue apartment that my parents owned but did not occupy. In New York, there was privacy. In New York, my illness bloomed. The behavior took on the feel of a religious practice, lulling me into a kind of trance. While I binged, my brain emptied out. My universe diminished to a bite that I could swallow. Nothing existed beyond the curve of my spoon and the melting, glistening dune of ice cream that slid off it onto my tongue.

The Modern Girl’s Practical Guide to Throwing Up in the City

- Always leave the apartment with a book bag stuffed with old newspapers. Later, you will empty the contents of the book bag into a trash can and then fill it with your shopping bags from the supermarket. That way, the doormen in your building won’t see you carting groceries home day in and day out.

- Rotate supermarkets. You’d be surprised how quickly cashiers will begin to recognize you and give you funny looks. You’re in the city; you’ve got lots of options. Use them. Also, rotate cashiers and checkout lanes.

- When selecting your purchases, keep an eye out for bargains. This is an expensive illness. Besides, as you well know, it’s quantity, not quality, that counts.

- Always throw some vegetables and other healthy items into your cart. You’ll be much less likely to raise eyebrows if you’ve got a few nonbinge purchases added to the mix, and you’ll need a carrot, or some other brightly colored vegetable, anyway. (See rule number 6.)

- Make sure to buy something for the walk home. Otherwise, the trip will seem interminable, even if it’s only a few blocks. A king-size candy bar is ideal for this purpose. With practice, you’ll be able to time it so that you swallow your last bite just as you’re rounding the corner onto your block.

- Before you begin your binge, eat a carrot or some other brightly colored vegetable. That way, when you see a splotch of orange during the purge, you’ll know you’ve emptied your stomach of everything you ingested.

- The order in which you eat foods is very important. The smoother, more liquid items — like ice cream, or cereal with milk — are the easiest to throw up. Starting with those foods will lay a foundation in your stomach and help the drier items — like cookies, muffins, and cakes — come up more readily.

- For the same reason, drink lots of fluids before and during your binge. The more fluids you have inside of you, the easier it will be to throw up.

- If you have long hair, remember this catchy phrase: Tie it up, then throw it up. What could be more embarrassing than inadvertently splattering your hair with vomit and not noticing till hours later?

- Put on some music to drown out the sound of your retching. Apartment-building walls are thinner than you think, and neighbors are nosy.

- Continuous toilet flushing is also likely to arouse your neighbors’ suspicion, so flush sparingly. On the other hand, be careful not to wait too long between flushes; you certainly don’t want to be stuck with a clogged-up toilet.

- When you’re done purging, you’ll need to clean yourself up. Wash your face and perhaps change your shirt (depending on how messy you are). Brushing your teeth will remove telltale stains and odors and has the added benefit of eliminating the harmful acid residue from your mouth, slowing down the inevitable decay your teeth will suffer. Perhaps most important, washing up puts valuable psychological distance between you and the awful thing you’ve just done (again).

- Dispose of food wrappers and containers discreetly so as not to arouse suspicion among the maintenance workers in your building. Crumple, fold, and compress wherever possible, putting smaller boxes into larger ones. With practice, you can collapse the trash from a full-blown binge into a single half-gallon ice-cream container. Minimizing the volume of your trash also minimizes the enormity of your behavior: how bad can the binge have been if what’s left behind is smaller than a bread box?

- Vow never to do that again.

There was a hierarchy of eating disorders rooted firmly in my head: at the highest point hovered a see-through, anorexic angel; below her, a row of bulimics stood at attention like sentinels guarding the throne; and below them — below us — swarmed a legion of overeaters, commoners.

I binged and purged with greater frequency and greater intensity, until the rest of my life was an interruption — going to work every morning at the highbrow Fifth Avenue bookstore that had hired me at the end of the summer, seeing high-school friends when they came home for vacation, talking on the phone, whatever. This was the only thing I did with consistency and effort. My bulimia defined me.

The world during that time seemed to confirm my reduced identity. I had been working at the bookstore for four months when my manager pulled me aside one day and told me that, because I had done so well, she was going to give me greater responsibility. “From now on,” she offered brightly, “it will be your job to make sure, every morning, that the bookmark holders at the registers are stocked.”

I quit the next day. I was irritated by her patronizing treatment, but I also saw it as confirmation of who I knew myself to be. I could not get ahead even in this how-would-you-like-to-pay-for-that world. Even here, filling up empty receptacles was all I could manage.

Then I took a fiction-writing class taught by an elderly woman who wore sandals and rags and long, greasy pigtails. When she spoke, balls of spittle spun in the corners of her mouth. The third week of class, I read aloud from a short story. “This is a perfect example,” my teacher said when I was through, “of how not to write.” I didn’t show up after that.

The truth is, the excerpt was from a story I had written in high school. I had not done any creative writing since then, nor had I started again once the class got underway. I was an impostor, digging through old files, putting the polish back on a dusty, retired self and trying to pawn it off as new. And even that didn’t fly. Had I ever shone?

Still, I clung to the belief that some creative spark lived inside of me. And from that belief I developed the cocky conviction that I would someday be famous; I just had to find the right medium. It seems an impossible juxtaposition: I was capable of nurturing this grandiose fantasy about my future at precisely the time when I could sustain only the narrowest, least forgiving conception of myself in the present. I think the fantasy reflected a last-ditch effort at self-protection. The prospect of emerging from this nightmare to live an average, unremarkable existence would not have kept me going. I needed big hope, outlandish assumptions. Only a puffy, life-preserver dream would keep me from drowning; I was that heavy and low to the bottom.

I took an acting class, convinced that I would be discovered. We met in the dimly lit front room of the instructor’s Greenwich Village apartment and were encouraged to let ourselves go when there. We spent the first ten minutes of every class doing whatever our bodies happened to direct us to do. We grunted loudly, we sang, we crawled on the floor, we touched each other if the impulse struck us. We were, according to Claude, getting reacquainted with each other, with the space, with our own bodies.

Next, Claude instructed us to imagine that the air was actually sand. We adjusted our movements accordingly. A few minutes later, he would prompt us again. “The air,” he would pronounce, “is now fire.” And a few minutes after that: “Now . . . baby oil!” I had a hard time with this exercise. I tried to feel the dry grains of sand scouring my lungs, to conjure the blisters popping on my roasting skin, to lean into the slick resistance of the baby oil. But I could never convince myself that the space was filled with anything but the same old air, slightly chilled, carrying on it the smell of the slim cigarettes Claude smoked in the kitchen during breaks.

One night, as I was attempting to fight my way through the flames, I began to feel lightheaded. I saw sparks with my eyes open, and full-out fireworks when they were closed. My fingers tingled, cool one second and then hot the next. These sensations excited me. Perhaps I had made some breakthrough in technique and was finally experiencing this warped, on-fire world the way real actors did. And then it occurred to me that I had thrown up just before heading downtown to class; the dizziness and disorientation were simply the byproducts of the purge. I had not, after all, escaped.

I opened one eye to see how the others were reacting to the fire. A woman was crouched in the corner, wailing.

Bulimia. . . . I could not even bring myself to write the word in my journal. Instead, I wrote “b.,” as in “Today we spent the entire time talking about b.” Maybe the whole word was too much to handle at first; I needed to learn it piece by piece, slowly.

My teeth began to hurt. Raw nerve endings rippled and stirred when I bit down on food, when I brushed my teeth, even when I smiled into a breeze. The ridges that striated the enamel had smoothed over. My front teeth had shortened and thinned noticeably, top and bottom; each one now had a translucent gray border, as even as the window trimming on a house. I could see my tongue wiggling behind them. And my molars had worn down to stumps, all craggy definition lost.

I became obsessed with my teeth. I pulled out old photographs and studied them carefully: my teeth on the beach in the Caribbean; my teeth in my grandmother’s kitchen; my teeth in Red Square; my teeth at my brother’s college graduation. In real life, my smile had won me compliments. Now I sifted through these pictures mourning its demise. I couldn’t believe how thick my front teeth used to be, how pronounced their ridges; they hung like theater curtains from my gums. And my canines: so long and tapered, touching the red pad of my tongue like a ballet dancer on pointe.

Several times a day, I checked on the condition of my teeth in the mirror. I could not stop flicking my tongue across them, testing their eroded contours. And night after night, I dreamed about losing them. In some dreams, they crumbled into white sand that spilled from my lips; in others, they flew out of my mouth whole, like a flock of doves.

One day I bit into a lollipop and a piece of tooth, about the size of a stud earring, chipped off. I found out through feel: suddenly, an opening that the tip of my tongue could slide through. Another day soon after, a filling from a root canal lifted out, the bond weakened by the daily current of acid. I turned the glinting piece of metal around in my mouth, slid my tongue into the deadened crater of tooth where the filling had nestled. I was disintegrating, my body sloughing itself off, bit by bit.

At the dentist’s office, I had to fill out an intake form, which asked, at the very end, Is there anything else the doctor should know? I paused for a moment and then decided it was time to confess. “Bulimic,” I wrote. The word puffed up like a black cloud in the blank space at the bottom of the page.

Dr. Miller applauded my honesty. “Good for you,” he said. “Some women come in here and don’t tell me anything. But one peek inside and right away I know what’s going on. The mouth of a bulimic can’t lie.”

My story, then, was inscribed into my body; my mouth could not keep its mouth shut. All it took was someone who could read the language of the flesh, the way a geologist reads the muted language of rocks. Even if I had wanted to keep this illness a secret, my body would have betrayed me.

“The good news,” Dr. Miller went on cheerily, “is that the erosion is still pretty minimal. Now we can work together to slow down the damage. One thing you can do to help out is smear some baking soda on your teeth before you throw up.” He made tiny circles in front of his mouth with a gloved forefinger to demonstrate. “That will protect them from the acid.”

Dr. Miller was a happy man. He shared a practice with his father, and you could tell that the legacy he had been handed suited him. He bounced around the office in his springy tennis shoes and wiggled his fingers energetically into his latex gloves. He was freckled and young, and he exuded a kind of unguarded, naive traditionalism: right here, this was the good life — why look elsewhere?

Fortified with Dr. Miller’s practical piece of advice, I left the office feeling hopeful; the glittering sidewalk seemed to wink up at me in the sunlight. Things weren’t so bad, after all; I could help myself through this. I stopped at the supermarket on the way home and bought a box of Arm & Hammer.

But the baking soda sat unopened in the kitchen. Dr. Miller’s little tip had made sense in the context of his office, where things could only get better, where you could always look on the bright side and you didn’t have to work that hard to extract a bit of good news from the situation at hand. In the throes of a binge, however, I had no use for rationality. Besides, the cycle could not have supported that kind of interruption. The momentum of the binge propelled me right into the purge. Each episode played itself out like a roller-coaster ride, where there is only the slimmest fraction of a second between the ascent and the fall.

There were moments, those first few times after my visit to Dr. Miller, when I did think about the box of fine white powder waiting on a darkened shelf, pert and stocky, all good intentions. So simple, really; why don’t I just go into the kitchen right now? The problem, I realized, wasn’t only that I couldn’t integrate my dentist’s advice into my routine; I also didn’t want to. Applying a layer of protection to my teeth actually conflicted with my agenda. Part of the plan was destruction.

I continued to see my therapist during that year, traveling to New Haven one afternoon a week and returning in the evening. I expected that insight would replace illness and waited for self-awareness to flood my brain, disinfecting it like bleach, stripping away all the bugs and glitches, the dirty quirks and habits. But it didn’t turn out that way. Understanding, first of all, did not announce itself, but rather snuck in through some back door. And my illness simply moved over to make room for it. The two were entirely compatible.

Whatever interpretive skills I had picked up and been able to apply to the rest of my life failed me when it came to my eating disorder. There was no rhyme or reason to my behavior. Some days I felt terrible and ate more or less normally; other days I felt life wasn’t so bad after all and found myself downing a box of Nutter Butters. I could not divine the logic.

“What led up to it?” my therapist would always ask, when I revealed that I had binged and purged earlier that day. I could tell her what had happened in the minutes and hours before these episodes, but I could not identify a trigger, or a cause. The story had no clear plot line, no unifying motive; it was just an accrual of seemingly unconnected events. I bought a pair of shoes and then stopped at the supermarket on the way back; I had dinner with a friend, and when I got home I just kept eating; I woke up from a sound and dreamless nap and went right into the kitchen.

My therapist would prod a little, trying to stitch a thread of meaning through these separate swatches of experience: “What were you thinking about beforehand? What were you feeling?” I could never remember. Think back, I’d tell myself. It wasn’t that long ago. I’d sit still on the couch in her office and listen for a strain of internal dialogue still lingering in some nook in my head. But I couldn’t hear anything, and the harder I listened, the more complete the silence was. It was as though every episode erased the memory of whatever thoughts had preceded it. These lapses frightened me. They were a failure of power and control, a bow to nonsense, a further abdication of self.

When I had time to kill before the next train back to New York, I’d stop at a coffee shop on Whitney Avenue. The coffee they served was bland and burnt, but it was a townie establishment, so there was no chance of running into someone I knew from school and being forced to explain what I was doing in New Haven.

One afternoon in March, I was sitting at the counter with a coffee and my journal when a guy sat down next to me. He had stringy blond hair that just touched the collar of his army jacket and a scab the size of a raspberry above his lip. He swiveled toward me. The left sleeve of his jacket was empty, folded at the elbow and pinned to his chest.

“Hi,” he said. His eyes were deep blue and streaked with white, the way Earth looks from outer space. They kept roaming the room; he could not focus.

“Hi,” I said back to him.

“So what are you writing, anyway? Are you a writer or something?”

“No, it’s just a journal,” I said, closing it up.

“Yeah? I write a lot, too. Stories, you know, stuff like that. In notebooks. And I draw. My whole bedroom is covered with drawings, all the walls, covered.” He made a sweeping gesture with his right arm. “I’m missing an arm,” he said. “Did you notice?”

“Yeah,” I said. “What happened?”

“I was drunk. I was really drunk and fucked up on some other stuff, too. It was New Year’s Eve. Me and my friends took the train to New York to watch the ball drop. I fell off the platform in Grand Central Station — you know, Grand Central Station, in New York? Anyway, I got electrocuted. That third-rail thing is no joke. I had to get my arm amputated.”

“Wow,” I said. “When was this?”

“Oh, I don’t know.” He thought for a minute, his face clouded over. “Seven, or maybe three years ago. Or seven, maybe. Wait, how old am I?” His face cleared up. “How old are you, anyway?”

“I have to go now,” I said, signaling for the check.

“So maybe I’ll see you next time,” he said, getting up with me, leaning over. “Can I have a kiss before you leave?”

He smelled unwashed, his legs looked withered, he was a complete stranger, he was crazy. But I kissed him anyway, right on the lips — reaching out for his lost limb, his disjointed story. And then recoiling. I ran from the coffee shop. I ran for three blocks. Panting, disgusted, I spat on the sidewalk and then wiped my mouth until it was raw. I could not make myself whole.

“These things,” my therapist said, “sometimes take on a life of their own. The behavior outlives its usefulness but sticks around anyway, out of habit.” To help me kick the habit, she recommended group therapy with a behavior-modification specialist.

I went to group therapy but never bought into it. I just could not get with the program, which was part brainstorming, part cheerleading, and advanced at a glamorously quick pace, skimming across surfaces and then continuing on.

Ellen, the therapist, slouched in her armchair like an awkward teenager. She was overweight. I was immediately suspicious. She’s fat! I thought disdainfully. What does she know about controlling your impulses?

“Can anyone think of something to do besides raid the fridge?” Ellen asked at our first session, nodding at the room in anticipation. We came up with a whole slew of alternatives: call a friend, write in your journal, do some deep breathing, rent your favorite movie. The list went on, but while the others were getting more and more enthusiastic — Wow! Look at all my options! — I kept thinking that we were ignoring one essential fact: when you want to binge, nothing else — not a walk in the park, not The Philadelphia Story — will do. The enterprise seemed doomed the way Dr. Miller’s advice had been, a naive appeal to reason.

And yet it worked, somehow, for the others. Over the course of the next few months, women came in and proudly reported their breakthroughs.

I sampled from our list of strategies, too, but my efforts never yielded those kinds of results. The most they ever did for me was delay the inevitable. By the end of the three-month session, I had not changed.

There was no rhyme or reason to my behavior. Some days I felt terrible and ate more or less normally; other days I felt life wasn’t so bad after all and found myself downing a box of Nutter Butters. I could not divine the logic.

“You should come to Israel,” a family friend advised. She did not know the details; she knew only that I was in a serious slump. “Come to the kibbutz. You’ll be healthy; you’ll make friends. It’ll get your mind off things.” I had always maintained the hardheaded conviction that you can’t escape yourself; people who thought, If only I were somewhere else, seemed naive and lazy. But the crackly overseas connection, with its bizarre three-second delay, had suggested that my friend had in fact called me from someplace so far away that, if I got there, I might feel different.

That summer, I went to Israel and worked on a kibbutz for six weeks. I didn’t throw up once while I was there. I had roommates for the first time since my illness began and spent almost no time alone. But I don’t think it was lack of opportunity that broke the cycle, because if circumstance alone is keeping you from satisfying your needs, they still fidget and fuss inside you. And my need, the desperate compulsion that had governed my life for so long, behaved itself in Israel. I did not find myself always wishing for a moment alone, a place to sneak off to, a supermarket. I was quite happy with the setup, sharing a tiny concrete cabin with two other volunteers and eating my meals at regular times with hundreds of other people in an enormous mess hall. Besides, bulimics are good schemers. Desperation breeds creativity. I could have found a way if I had wanted to, if the need had demanded so stridently to be satisfied that I could think of nothing else.

Bingeing and purging were in fact so far from my mind that I didn’t even reflect on their sudden absence from my life. But everything was different. I was in the middle of the desert, with no reference points. Why would I notice the absence of this one pattern of behavior when all my old routines were supplanted? I, who used to turn out the light in the middle of the night, who had slept well into the afternoon, was now waking up at five o’clock in the morning, in the cold and dark. I, whose contact with nature had come primarily from summer camp, was now picking peaches until noon six days a week, getting dirty, sweating in the sun. The sun itself seemed new, a shockingly megawatted, souped up version of the dull star I had always known, a dirty light bulb barely glowing in the Manhattan sky.

Was I just distracted, then? Had Israel seized all of my senses with such vigor and charm that I simply forgot? Perhaps. But that doesn’t explain it all. New York City — New York City, after all! — could have distracted me, too, if I had wanted to be seduced away from my sad routine and into the litter and the glamour of the streets.

Was my behavior site-specific, just one of the many trappings of my life in New York — like my Doc Martens, my winter clothes, my lipstick, and all the other things that hadn’t made it into my suitcase? Was it something that simply made no sense in this foreign context? Here, you ate tomatoes and cucumbers for breakfast. Here, small children splashed raucously in the pool and stepped barefoot with confidence across the searing pavement, their callused feet immune to its heat. Here, mothers were busy working in the factory, or the orchards, or the kitchen; they came in all shapes and sizes and still managed to look beautiful — their varicose veins, their wrinkles, their toenails ungroomed, thick as flagstone, jutting out past the tips of their sandals. Was bulimia, here, a word with no translation?

And yet I did not leave it behind entirely. In Israel, too, I thought a lot about my body. I thought about the deep, rich brown my skin had turned. I thought about how the hours I put in climbing up and down ladders, reaching into trees, and carrying buckets full of peaches had hardened my loose flesh into muscle. I thought about how my body had gotten not only tighter but smaller; I was eating less. (Why? Decreased appetite, or increased willpower? I couldn’t tell.) I noticed the extra room in the waist of my shorts as I stepped into them in the dark every morning. Every afternoon, as I put on my bathing suit before heading to the pool, I studied my new body in the mirror. The mirrors on the kibbutz were dirty and poorly lit, but they still gave you an image you could work with. I turned to one side and then the other; I lifted my arms in front of me and checked out the contours; I stepped back a few feet and took in the whole me from farther away. I was pleased with the transformation, but too preoccupied with its particulars. Happy thoughts still qualify as obsession if you return to them a thousand times for reassurance.

And then there was the matter of the peaches. The kibbutz had no restrictions on snacking on the produce, but for the first several days, I felt shy around the fruit. I was respectful, strictly business. The peaches were huge, the size of softballs, and a pinkish white even at their ripest. I picked them carefully from their branches and rolled them gently into the bucket that hung at my hip. I did not want to bruise their perfect skin.

One morning, I picked a particularly soft peach. Just plucking it left fingerprints; there was no way it would make it to market without damage. So I ate it. It was shocking and wonderful: that something so blandly colored could yield this kind of pure, sugary sweetness; that just beneath the dry, fuzzy surface there could be so much clear juice ready to run. I spit out the pit. It arced upward, a wet, bright orange sun traveling across the sky, and then landed softly in the dirt. Let another peach tree grow! I thought, wiping my hands on my shorts. I examined the pit before picking up my ladder and heading on to the next tree in the row. The ants had found it; they were picking it over. It looked like a sea treasure wrapped in black netting.

The peaches and I had broken the ice, and it was only a matter of time. I ate two peaches the next day; the day after that I ate five. By the end of the six weeks, I was eating as many as twelve peaches in a morning. My chaste celebration of that natural sweetness had slid clear into decadence. I could not keep corruption at bay. It had followed me into this desert orchard, where I stood on my wobbly ladder, suntanned, muscular, my arms and legs crisscrossed with scratches, eating. True, these were not cookies or candy bars. But still: I ate until I was full and then beyond that. I could not pass up a good-looking peach.

When it came time to leave the kibbutz, a tiny itch had registered inside of me. I left with great sadness, with a promise to return, and also with something like relief.

I returned to the States at the end of the summer and returned to bingeing and purging, too. Just like that. No grace period, no slow descent. The pattern came rushing back to me along with every other detail of my life — the height and shape of the toilet seat the first time I sat down to pee, the size and weight of a nickel in my palm, the smell of freshly brewed coffee after six weeks of Nescafé. It was unfamiliar for a split second and then perfectly normal once again.

Yet I also remembered that I had stepped outside of this pattern, even if only temporarily, even if incompletely, and even if I could not figure out why. That memory was both solace and torment, for the measure of the ground I had gained was also the measure of the ground I then had lost.

I went back to college, back to seeing my therapist, and, over the next few years, my bingeing and purging slowly tapered off. The change had nothing to do with increased self-restraint (I had none), or with new mastery of behavior-modification techniques (I had given up on those long ago). Nor was this change the byproduct of any kind of overall progress I was making. In fact, I continued to sink into deep and prolonged depressions.

It was as though the illness simply got bored of me, bored of itself and its own stupid and charmless predictability. The binges became smaller and less frequent. The purges were almost mechanical, a rote procedure my body half-heartedly put itself through out of a sense of obligation, or nostalgia. Need faded away. The behavior yawned and slacked off. I noted its change of heart and marked its errancy.

But I didn’t dwell on the shift, because my focus had shifted accordingly. I began to experience life as the spaces between episodes, not the episodes themselves. When you recover from a prolonged sickness, it leaves your thoughts. You get back to work and exercise and eat banana-nut pancakes on the weekends. You are thankful that you once again have the strength to do laundry, perhaps, but you do not consider for too long how the bedsheets, now laundered, no longer carry the ripe, dark smell of illness in their weave. Though, as I’ve said, I had little hope of ever feeling happy, I wasn’t hopeless any longer about my bulimia. I had started to believe that it would eventually go away.

Finally, in the middle of my senior year of college, two weeks passed, and then a month, and then I lost count altogether. And I felt safe saying that I would not binge and purge anymore.

A protracted but nonetheless quiet and dignified death: that would be the most boring of possible endings to the story of my illness. But it didn’t end there. Something else happened. My illness took on a new incarnation.

I have struggled to find appropriate words to describe this, to give a clear picture of what happened without offending. Yet it seems that only the most direct, unmannered language will do, because the behavior itself was a smack in the face of civility. I need to tell the story the way it was told to me, my teeth and tongue fastidious, relentless, not eliding one detail.

Instead of bingeing and purging, I began to regurgitate food after meals — a mouthful at a time — rechew it, and then swallow it again. I would do this until the food turned so sour that it became unpalatable. Sometimes the whole process took fifteen minutes, sometimes much longer, depending on what I had eaten. There’s a word for this bizarre ritual, which means enough people have performed it and then confessed to their doctors to earn it a clinical appellation. Rumination, the professionals call it.

In some ways, this behavior seems to fit onto a continuum with the bingeing and purging it replaced. It certainly looked like a less extreme version of the original, a storm that had lost some steam, now stirring waves just high enough to kiss the gunnel where they had once spilled over violently onto the deck. It had some of the same qualities, too. It was compulsive, if less frenzied: the way I cataloged all of the data I had gleaned about food; the way I allowed the behavior to determine what I ate and when.

But in other ways the rumination seemed to veer off in new directions, to be an entity unto itself — a neighboring star in the same constellation, with its own gleam and pulse, its own distinct coordinates in the sky. It had a certain preciousness, a kind of modesty, that distinguished it from the almost cavalier excesses of the binge-purge cycle. It felt miniature and careful, a studied gesture, where the bingeing and purging were overdone and imprecise, a drunken lurch. The bingeing and purging were all about volume; I consumed and then dismissed food in vast quantities, and with an enraged wastefulness, a hurtful indifference: each bite as worthless as the next, all of it interchangeable. Here, quality mattered, not quantity; I obsessively rehashed the same tiny portion, as though I could not possibly get enough out of it, that’s how valuable it was, how endlessly fulfilling. The rumination was an exercise in conservation. It was the new austerity in the wake of previous decadence.

And unlike the bingeing and purging, it did not come in two contradictory parts. There was no doing and then undoing, transgression and then consequence. There were no ambivalences duking it out while I waited, beleaguered, knowing the outcome too well. It was a unilateral ritual. It did not feel like a war.

It felt, actually, like peace. It was satisfying, intensely pleasurable, soothing the way bingeing and purging had been, but without all the violence: The aggression and rage had been replaced by tenderness and appreciation, which softened my experience and eliminated the blinding rush to be done. Each time, in fact, I wanted it to go on forever. Parting ways with my meal once and for all saddened me; the ending meant disconnection, a kind of loss.

Perhaps it was these specific virtues — respectfulness, frugality, tidiness, tender regard — that made my shame recede, diluted my self-hatred. Complacence had settled in over restless dissatisfaction: I could live with this. I kept my behavior a secret, to be sure, but this new secret didn’t disturb me the way the old secret had. I managed to reduce and compartmentalize the rumination. It became a function of who I was, rather than the other way around — a strange and private comfort whose weird specifics I chalked up to my own idiosyncrasy.

And then, finally, for no reason I could discern, the rumination subsided, too. My stomach turned as still as a frozen lake. The illness abandoned me for good.

I do not demand constant appraisals from my boyfriend. I keep my dissatisfaction with my body to myself, knowing that neither confirmation nor contradiction would satisfy me, that both would fan the flames of my obsession. I refuse to check food labels. I do not own a scale.

I am now left with its legacy — a suspicion of food, a distrust of my own appetite, a permanent discomfort with my body — though I have figured out how to manage it. I will not, for example, look at my reflection in the full-length mirror for too long. Staring always leads me down the same road, and I’m tired of the journey. My disdain was once innovative, full of fresh surprises, but the novelty wore off long ago. I do not demand constant appraisals from my boyfriend. I keep my dissatisfaction with my body to myself, knowing that neither confirmation nor contradiction would satisfy me, that both would fan the flames of my obsession. I refuse to check food labels. I do not own a scale.

I worry less about food, but still I worry. And, though I do not resort to the old measures, some of the old thinking still lingers. I might, instead of throwing up a particularly heavy dinner, decide to go for a longer run the next day. Running is good for me, it keeps me healthy, but I am still motivated by the same unhealthy principle: punishment for previous excesses. Or I could put it this way: True, it is an unhealthy thought that gets me out the door, but I am running, after all. I am running! And when I run the perspiration glistens on my skin, my brain turns off and lets my legs and arms and lungs take over. My sneakers hit the pavement like a heartbeat: dumb rhythm, happy life.

And then how I live becomes not a concession but a compromise, which suggests that while I may have made some adjustments, I have not rescinded control, and that is the most that I can reasonably hope for. I will bend a little from the burden, but my legs are strong from running; I know they will not buckle. That is enough.

Recovery stories often wrap up with some kind of conversion: “I used to drive myself crazy trying to look like someone else, but now I love my body,” or, “Finally, I see that I am beautiful, head to toe, big hips and all.” Every negative thought and impulse and behavior has been eliminated, through some combination of great effort and revelation, and supplanted by body love.

Such sweeping proclamations don’t convince me, but I understand the push to make them. I have not learned to cherish my physical self; I have simply learned to give up wishing. I have not persuaded myself that my body is just fine the way it is; I have trained myself not to participate so wholeheartedly in the debate. And I have fought so ardently to arrive at that stance, as tepid and unenthusiastic as it is, that it begins to feel like love.