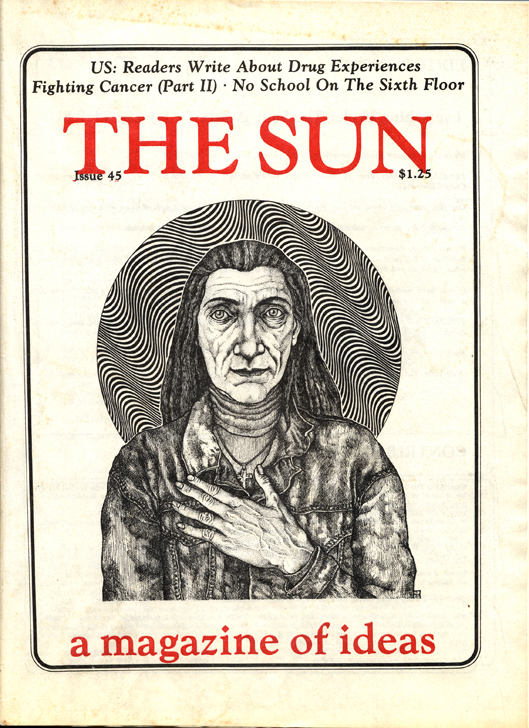

The following report describes a unique experience in learning — conducted with young adolescents from an “intensive care” psychiatric ward and an equal number of young adults from city streets. How these young adults reacted to each other and to a common learning experience is the basis of this report.

Last summer I found myself unexpectedly teaching school. My classroom was a hallway on a deserted floor of a mental hospital. The students were five adolescents hospitalized for psychiatric treatment and eight “street kids” paid to attend school. The school program was a part of an unusual experiment to prepare psychiatric patients for the real world.

The inner-city street kids were hired by the mayor’s office as part of a summer employment program for disadvantaged youths. It was hoped that they might serve as therapeutic models for a peer group of severely disturbed young adults.

This introduction of the real world into the hospital setting was a unique situation. Most psychiatric hospitals attempt to help patients resocialize through companionship or volunteer community helper programs. But these efforts to ease the patient into the outside world take place after the patient is released. This care is comparable to “here’s the name of a friend, and here’s a new coat” given to individuals leaving a prison.

Of course, it takes more than a new suit to catch up with what’s current on the outside. Especially if you’re an adolescent. So a special summer school was initiated. Kids called “street wise” were paid to help kids called “crazy” face the eventuality of leaving the hospital. It was an adventuresome idea.

The street kids were an amalgam of personalities. The self-proclaimed leader of the group was a young Chinese woman named Mary. Ideas shot from her like darts. As she talked, she literally painted words with her hands. Another kid named Johnny T. fielded Mary’s enthusiasm with a gold-toothed smile. Johnny’s radio and knit cap gave him away as a kid from South Hampton Street. He was one of those rare “tough” kids who could go anyplace.

Georgia was simply big. She was a large black woman who looked and acted as if she was in continual choir practice. She glided quietly into any setting and then anchored. She didn’t say much, but she hummed a lot and you felt good being in her company. Alyce was also black, but she was different from Johnny T. or Georgia. Alyce’s middle-class background kept showing. She was always acting to please, to find someone a chair, to share her latest accomplishment.

Whereas Alyce moved to accommodate the world, Vicki, Lisela, and Philip gave it color. They were from the city’s Latino neighborhood. Their words overlapped and spilled into the air like machine gun fire. Staccato expletives about boyfriends, marriage, El Salvador, and a hundred incidents were ignored or absorbed by most of the kids. For Richard Lee, a tall Chinese kid, the salvo of words was something to dodge. With each surge of verbiage, Richard would wince and back up then spin and sit down, only to stand and turn again. Richard was a matador turning away from words and motion cast in his direction. Like a wind-up toy twisted too tight, you wanted to hold him for a minute and let the extra juice whirl away.

The final outside student was Ellen. She was the only white kid in the group. Shy and boyish in her heavy jeans and sweater, she was unique in one respect. Her younger sister was one of the psychiatric patients.

Although the city kids reflected a tremendous diversity in style, they held similar opinions about working with peers who were mental patients. They expected the patients to be “bedridden,” “mentally retarded,” and “unable to make sense.” They felt the patients would be “talking about things that don’t exist,” “constantly running around tearing things up,” and “always yelling like on TV.” The greatest concern held by the city kids was of “being beaten up by a crazy patient.”

The patients in the school program were also quite diverse. Leona was the group cheerleader. With her broad shoulders and her “rocker” walk, she looked like she was skating for the Bay Bombers. Leona was hospitalized for aggressive hostility. Her sister Ellen explained that Leona hit people, was always in trouble, that her stepmother couldn’t stand her — “she could never come home.” Leona’s closest friend was Danny. Like most of the patients and outside kids, Danny was sixteen. He looked about eight or nine years old. His hair stuck up in the back and down over his eyes in the front. He looked like a Cub Scout in pursuit of merit badges. His body could run and jump over fire plugs, but his mind seemed fixed on questions of sexuality. Like a stuck record, he’d ask, “How long is your cock?” To the girls, he’d smile and ask, “Can I squeeze your tits?”

Lynell was one patient who never heard Danny’s question. Just as Danny’s speech repeated, Lynell’s every movement was ritualized. Her frail body would crank to a standing position, only to reseat, then stand again, and sit again, and stand again. Her walk was several steps forward, followed by a pivot and steps in another direction. Every action was methodically traced over and over, a process called “perseveration.” A crusty webbing of dried tears covered Lynell’s eyes like spider webs. Tobacco stains crawled over her fingers. Her uncombed hair and disregard for clothing made her look like an aged woman.

Of all the patients, “Zero” was the most mysterious. He looked like an average suburban senior high school student. In many ways, though, he was anything but average. Zero was an electronics wizard. Dying TV sets came to life under his care. At his command, hospital elevator doors would open to an exposed shaft. He could listen in on any phone conversation coming into the ward. And with little trouble he could vanish. In a ward charged with emotion he had found the secret of quietly blending into the scenery or exiting through an unnoticed door. So he lived in an electric world and played ghost to the real world.

Rella also hid from reality. Her escape took the form of silence. She never spoke. Periods of silence were interrupted by periods of severe vomiting. Her life swung back and forth from silence to physical illness.

Just as the city kids shared certain expectations about patients, the patients expressed a set of opinions about their counterparts outside the hospital. Generally they felt the city kids were “loud,” hard-looking,” and “very dangerous.” That “those people will pick on us,” that “they’ll make fun of us,” that “they don’t know about a hospital like this.” And, “they’ll probably hurt us, kick us and stuff.”

They were two groups of kids separated by worlds of experience. Kids from city streets, called “disadvantaged,” being asked to work with kids called “crazy.” Both fearful of the other. Both willing to risk abuse and danger in order to attend an unusual summer school on the sixth-floor hallway of a hospital. What happened when these two groups actually met was the basis for some unexpected learning, some surprises, and a new definition of the word “mental.”

School didn’t exactly start with the pledge to the flag. In fact, we didn’t have a flag, much less desks or books. What we did have was a huge billboard depicting a fanciful spaceship. It seemed like a natural introductory activity. We had a roll of tape, a paper billboard, and lots of arms and legs. The perfect educational plot. City kids and patients would meet each other — help each other — and share in the success of covering an ugly wall. Everything about this plot was perfect except for one thing. The tape. It stuck to everything but the wall.

Like learning, chaos can start quite innocently. In the case of the billboard, it started with Georgia.

Georgia used her massive size to tear delicate pieces of tape and affix them to the floor. They stuck up like grass. Actually, it was Mary’s idea. She directed everyone to start taping the edges of floored paper. Johnny T. smiled. Alyce tried to help by passing tape to waiting hands. It stuck to her and those she touched. Vicki and Lisela rolled the taped paper against the wall and continued talking. Richard and Ellen dutifully continued taping.

And the patients? Well, they were really needed. They greeted the sight of the street kids struggling with tape as a worthy adventure. Leona used her roller derby strength to hold up the top of the billboard. Danny used the moment to chase after Mary. His pursuit left a trail of sticky tape. Alyce stopped handing out tape. She sat down. Found herself taped to the floor. And was too embarrassed to get up. Lynell, the patient of a thousand directions, held out a corner of paper and wouldn’t let go. Rella just watched. Zero gave a nervous laugh and disappeared into an empty room. Johnny T. and Philip formed a human ladder to hold and tape the upper edges of the billboard. They demanded more tape.

Bodies pressed and sprawled against the paper. Tape was passed from hand to hand to wall. Tape hung like fringe from shirt sleeves and grabbed at unsuspecting feet. It did everything but hold the paper against the wall.

Suddenly the paper spaceship unraveled like an avalanche. It buried its tormentors. Covered them like a tent. No one escaped the falling paper and its tangle of tape. In slow motion Johnny T. and Philip cascaded downward with the roll of paper. For a moment there was nothing but silence, then a giggle, followed by yelps of laughter. Feet kicked to get free of the paper maze. Bodies scrambled into a stance. Tape was everywhere. It would take another hour to put up the paper spaceship. But it did get up. One spaceship flying through the hallway. It signaled the start of summer school. A fragile alliance between street kids and inside patients had begun.

They were two groups of kids separated by worlds of experience. Kids from city streets, called “disadvantaged,” being asked to work with kids called “crazy.”

The impact of street kids on patients was immediate and dramatic. In the first few days of school, Danny was the subject of all our attention. He was in love. In love with Mary and Georgia and Alyce and Vicki and Lisela and Leona and Lynell and Rella. He displayed his passions by squeezing girls’ tits, often by a surprise maneuver. He would spring from a hiding place or run full tilt down the hall to embrace his victims.

The girls went bonkers. They threw words of warning, “Cut that out!” Then words of consequence, “I’m going to smash you if you touch me again.” Danny took these taunts as encouragement. Mary finally explained — “It’s not that we don’t like you, it’s that we don’t like what you are doing.” Danny greeted Mary’s explanation with a smile. He put his hands over Mary’s breasts and tickled with his fingers. Mary grabbed his hands and pulled them gently to his sides. And held them there as she continued, “Boys don’t treat girls that way. My boyfriend doesn’t treat me like that!” And so it went. Danny received daily doses of street etiquette. The message finally got across.

We were doing some improvisational drama. Each student was given a statement on a piece of paper saying “you are robbing a train” or “you are washing a car.” The students were asked to find others holding a similar statement — and they were to conduct this search without using words. Danny started to follow Mary, then suddenly stopped. He became busy writing on slips of paper. In the midst of people acting out the robbery of a train or washing cars, Danny circulated his directions. Georgia showed me the result of Danny’s labor. He was distributing his version of the assignment. It read, “Grab Danny and give him a kiss.” Mary reacted by walking straight at Danny. She didn’t speak or hesitate. She kissed him gently. Danny had met the real world and found a way to touch it without being hit in the face.

By the second week of summer school, Vicki and Lisela institutionalized the idea of giving. They called it Kriss Kringle. Everyone put his or her name in a hat and then we drew names. I pulled Georgia. In the week that followed, it was my Kriss Kringle responsibility to give Georgia a gift each day. I was not allowed to tell anyone who I had drawn. At the end of the week we were to tell that secret. Gift-giving graced our presence for five days. I arrived one morning to find that my Kriss Kringle had prepared me a complete breakfast. An unnamed poet posted his (her?) work as a gift for everyone. Alyce received a lace fan. Someone gave Danny a copy of Penthouse. Lynell, the patient who looked so feeble, was given a bright ribbon for her hair. Johnny T. got a supply of batteries for his radio. Rella, the girl who was almost catatonic, found a daily supply of chocolate chip cookies. She began to share them. Several girls were supplied with perfume and makeup. Patients unaccustomed to using cosmetics and trying to look good suddenly started coming to school in eye shadow and traces of rouge. Lynell wore her new hair ribbon with a beautiful cameo. The cameo was something her grandmother had given her. Something she had kept in a bottom drawer. Something she now wore with a glow of pride.

Richard, the shy outside kid, took a Polaroid picture of Lynell and her finery. Lynell smiled. It was the first time I had seen that. The photo caught that moment. Lynell looked with disbelief at the photo, then walked away without saying a word. In a few moments, she lurched back down the hall. She was walking in a steady gait. That’s right. She was walking in a deliberate direction. No turns. No steps forward and back. She walked straight to Richard. Then she spoke. “What’s ‘photogenic’ mean?” Richard answered, “It means you’re beautiful.” Lynell smiled broadly. “The nurses downstairs said I’m photogenic.” Richard was as pleased and as rewarded as Lynell. The chemistry between street kid and patient was beneficial to both.

Perhaps the greatest gift provided by the street kids was the freedom they offered. Prior to the summer the patients had not been allowed on field outings. For many patients this meant they had been confined to the hospital ward for over a year. Midway through the summer, Mary argued for control of our budget. It was given. With the money, the students planned an outing to a roller rink. I was surprised to find that the hospital had no outing policy, and therefore had no outings. When Mary pursued this matter she found that the hospital insurance regulations prevented our use of private cars. Or buses. Or taxi cabs.

Mary found a solution — a form of transportation not stipulated in the insurance policy. She argued, if it’s not in writing, it must be permissible. Her solution was a joy to all. She rented a large black limousine from a local mortuary. On the designated day for our roller skating trip, we found a slinky Mercedes limo waiting in front of the hospital. Mary ushered everyone into the limousine. Three nurses volunteered to go along. The psychiatric ward had its first field trip. And much more.

It turned out that Lynell, the girl who could barely walk, could roller skate. And Rella, the patient who never spoke, asked to go along. We had rented the entire rink for ourselves. The manager was delighted with his early morning customers. We zoomed about. Johnny T. was silk on wheels. Leona, her sister Ellen, and Georgia inched around the arena wall. Alyce could skate backwards. Mary, Vicki, Lisela, and Richard formed a whip that sent both ends crashing toward the middle. Most of us practiced graceful falling and surprise stops.

After a few minutes of skating, it became obvious that the manager liked us. From his booth at the end of the rink, he announced, “All right, ladies and gentlemen, I have a special surprise for you today — haven’t done this in years — we’re going to do the Lindy.” A scratchy record came on. It sounded like a rhumba. The manager placed a bar in the middle of the rink. Our mission was becoming clear. “All right now,” the loudspeaker cracked, “everyone up for the Lindy Low. How low can you go?”

With the manager waving encouragement, we skated kamikaze style toward the bar. The object was to duck under the bar and still stay on your skates. Johnny T. whizzed through with a graceful dip. Danny and Richard approached the bar in a gale of laughter. They both crashed through it. Alyce skated full speed at it and then ducked into a ball that flew under the bar in a blur. Everyone clapped. Georgia and Leona walked up to the bar in a stagger, grabbed it, and walked through. More clapping. Danny raced toward the bar, again, and slid under like a baseball player sliding home. Zero circled the rink, then dashed at the bar. At the last second, he stooped into a crouch. The crouch exposed his invention; Zero had tied skates to each hand. They worked like the landing gear of an airplane. He swooped under the bar, riding on four roller skates and a grin. His victory was contagious. Everyone was rooting for everyone else. We enjoyed the greatest freedom of all — play.

Exhaustion finally took its toll. Skates were gingerly pulled off and stuffed back into boxes, rear ends were rubbed, the candy machine assaulted. As we were leaving, the manager of the rink moved to hold open the door. He was obviously pleased with the day’s events. In a final gesture of goodbye, he declared, “Nice group you have here. You’re good kids, not like those crazies that usually come here.” A secret smile traveled across twelve faces.

Summers don’t end. They tuck away someplace in your memory. And wait to be recalled. For me, this was a special summer. It was one of those summers when your ideas about things get tested and sometimes change. This had been a summer of change. At the close of school, I asked the patients how they felt about their counterparts from outside the hospital. They responded, “I thought they’d make fun of us, but they didn’t. . . .” “They don’t feel sorry for us. I like that.” One patient acknowledged, “I still feel embarrassed in front of them about being in the hospital.” The same patient then summarized how the patients generally felt: “We all blend together; they don’t seem all that special.”

As for the outside kids, their opinions about the patients also changed. They noted that patients came across not as crazy and destructive, but as quieter, less confident, and more reclusive than their community peers. They expressed surprise that the differences they expected to encounter were not as radical as anticipated. “They seem normal to me.” “The kids are different, but they’re not bad.” “I’ve kinda enjoyed their company.” Perhaps Johnny T., with his gold tooth and constant smile summed it up best: “They’re a little mental — you know, like me.”

“There Is No School on the Sixth Floor” is an excerpt taken from a self-published book, available from the author. For a copy, send $4.00 to: Ron Jones, 1201 Stanyan Street, San Francisco, California 94117. “The price of the book includes postage, envelope, and perhaps a drawing from my daughter.”