When I first heard that President George W. Bush would be making an Earth Day speech at Laudholm Farm, a sixteen-hundred-acre nature reserve near my home in Wells, Maine, it seemed as if a tainted bubble of exploitation had descended on the place, something especially unclean and dishonest. In an e-mail, a local activist said that the president’s visit had been announced with short notice, probably to avoid public protest, but the writer implored everyone to drop what they were doing and come to the planned demonstration. The tone of the message was stunned — Here? Laudholm? — suggesting the activist was insulted that the president had chosen us. I deleted it, thinking, Why bother? I should have been dismayed by my cynicism, but I’d gone beyond dismay.

My friend Mike Steinberg, the writer, once told me, “I survive this administration by reminding myself, every day, that these people don’t live in my house.” His words had provided me some relief from the helplessness I’d felt as the Bush administration had steamrolled over environmental protections. Now, however, the administration had come to my house. I was a member of the reserve and hiked the property’s perimeter path each afternoon. I felt like Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca: of all the gin joints in the world, why did Bush have to pick mine?

Later I heard news of the visit again on TV and witnessed the local newscasters’ pride in the president’s choice of location — as though it hadn’t been picked simply because this nature reserve was self-supporting and demanded nothing of the government. (Sure enough, during his speech, Bush would say, “Good conservation and stewardship do not rely on the government, and Laudholm Farm is a great example of people seizing the initiative.”)

In a carefully controlled spasm of anger, I drove down to the reserve to speak with someone. A young woman was staffing the office: probably in her thirties, wearing an Indian-print skirt and dangling earrings, her hair piled artfully on her head. I’d never met her, but when I presented my membership card, she knew who I was, suggesting that perhaps there were fewer supporters of the reserve than I’d imagined.

“This is an opportunity to protest the administration’s anti-environmental stance,” I told her. “You should refuse to allow him to make his Earth Day speech here and explain why to the press.”

The woman shook her head vigorously at my idea and launched into a speech about how much publicity the visit would bring the reserve, that more visitors meant increased donations, and the reserve might even become a tourist destination.

Her naiveté startled me. I made a few points I hoped would sway her: that welcoming Bush could be construed as support for his anti-environmental philosophy; that the president was only using Laudholm Farm to fortify his contention that federal protection and funding were unnecessary to preserve the environment; that people have short memories and would be unlikely to visit the reserve simply because of the news coverage.

She was not swayed. I sighed, thinking she was blinded by the glare of fame. I recalled how once, in Norwich, Connecticut, birthplace of the infamous turncoat Benedict Arnold, I’d asked a stranger for directions. After he’d given them to me, he’d added, “Benedict Arnold was born right here; can you imagine?” as if any connection to celebrity were better than none at all.

I asked the woman if she’d voted for Bush. She shook her head, clearly appalled at the suggestion. Nevertheless, she insisted that his visit would benefit the reserve. Giving up, I told her that I was dropping my membership.

She fumbled with some papers on her desk and said quietly, “I hope other people don’t feel that way.”

“Oh,” I snapped, “I’m planning to suggest it to everyone at the demonstration tomorrow.”

That night my husband, Kevin, suggested that my threat had been unfair; Laudholm Farm was caught in the middle of something it didn’t know how to handle. I had already thought of how difficult it might be for a small nature reserve to defy the presidential machine, to take a stand and make a public statement. Still, I didn’t care how difficult it was. I was embarrassed that I couldn’t feel anything but contempt for the woman in the Indian-print skirt. I shrugged my shoulders, made a face, and told Kevin that fairness no longer entered into the equation for me. I saw coercion as the only tool I had left.

That night in my bed, I realized that, along with my optimism, I’d been robbed of my sense of fair play by the appointment of the current president. Or rather, I hadn’t been robbed; I’d given my sense of fairness away and could reclaim it if I chose. The problem was that I no longer felt concerned with fairness, only with winning. I was filled with a vengeful desire for every Republican to be turned out of office regardless of his or her position. They had stolen from me the country I’d once had faith in. I understood that this generalization was akin to racism — as though Republicans were all the same — yet, to my detriment, I couldn’t move past it. I remembered what the Dalai Lama had once said: that compassion is best taught by your enemies. I was humbled by his compassion for those who were destroying his country, ashamed of my own pettiness, and mired in a self-destructive, useless anger.

Earth Day dawned in the low fifties with that particular spring dampness that hints of snow despite its being too warm. Winter lingers in Maine, outstaying its welcome, and snow in April isn’t unheard of. The Maine weather had been especially unpredictable this winter, bringing not enough snow to snowshoe, nor to protect dormant plants from the cold. The feathery green of awakening trees and shrubs lacked a certain vigor this spring, and flower beds had a halfhearted quality, as if the plants were feeling let down and refused to give their all.

In a kind of somnambulistic fugue, I watched myself pull on my jean jacket, get into my car, and drive up Route 1 toward Laudholm Farm, my windshield wipers battling the mist, the news broadcasting the latest body count in Iraq and the latest weather calamity in the U.S. The fog imparted an impressionist dimness that matched the surreal quality of the event: George W. Bush making an Earth Day speech practically in my backyard.

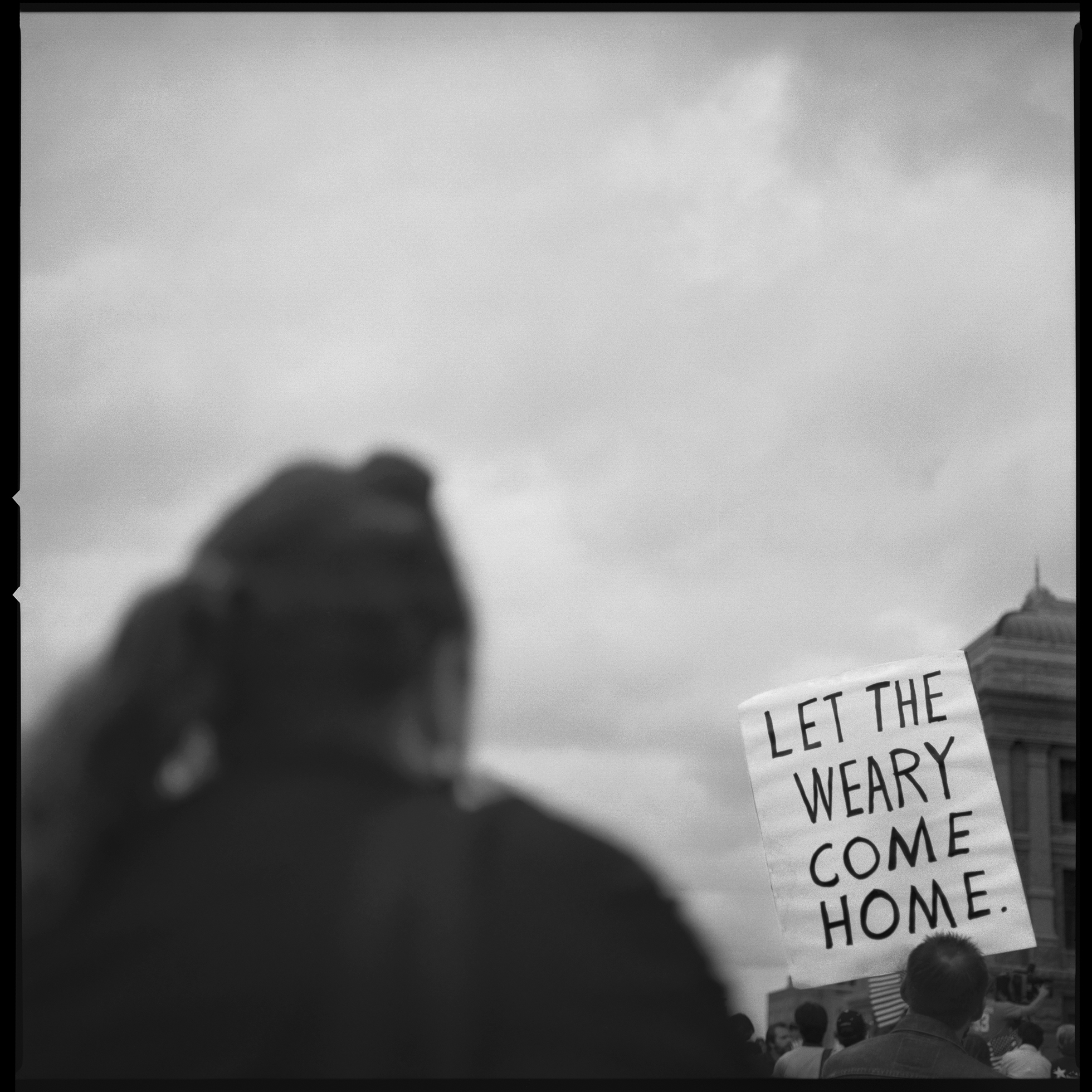

I pulled in at a restaurant near the reserve that had offered its parking lot to the demonstrators. People milled about at the edge of the road, carrying signs with the usual messages: This president is making war on Iraq, civil rights, and the environment. Impeach now! Babies for the environment (this last one carried by a young mother with an infant bundled against the cold). I joined a group of demonstrators who were my age and whose signs were particularly vituperative: All Clinton did was screw an intern; Bush is screwing the country. The group parted to admit me with smiles of welcome. Having no sign of my own, I felt naked until someone thrust one into my hand: Mother Nature won’t forgive.

I’ve always experienced a comfortable sameness at protests, a sense of camaraderie that allows me to fit into the crowd as easily as I might a roomful of friends, though recent protests have had a different feel from those I attended in the sixties, with their brash belief in possibilities. These days I sense instead a cynical weariness but a determination to do the right thing, as the planet issues its own protests by way of monsoons, drought, and unseasonable cold or heat.

This demonstration was not the smallest I’d attended — that prize goes to one at my old college to demand ramps for the disabled — and the organizers thought it was a wonderful turnout. The hundreds of thousands of us who’d marched against the invasion of Iraq had been considered a wonderful turnout as well, although the president had compared us to a “focus group.” Perhaps he was right; hundreds of thousands is a small percentage of the more than 300 million citizens of the United States. I miss the social conscience of the sixties and find our current national apathy as deadly as any disease. Examining the small crowd, I felt, at that moment, as though I stood in one of the last frenzied pockets of wakefulness in an America somatized by glitzy entertainment, full bellies, and cheap consumer goods.

Damn it, I thought. We are falling mute.

I stayed for two hours. I don’t remember the presidential motorcade passing us, though the press said it had. The sun remained hidden, a damp breeze blowing gray clouds across the sky. Traffic was thin. Protesters looked at their watches and apologetically noted that they had to go to work. Mothers left to take their babies home to nap. New demonstrators in suits and skirts appeared, taking an early lunch. There was commitment, but it was tempered by the reality of the times, both economic and political. We faced the road, waved at cars that honked agreement, ignored drivers who gave us the finger. What is this a demonstration of? I thought wearily. Futility?

When it was time for me to leave, I returned the sign to the person who’d given it to me.

That afternoon around 4:30, I decided to hike the reserve’s paths one last time and say goodbye to my favorite trails: my farewell tour, so to speak. After that, I’d leave the reserve to the visitors, the wildlife, and the staff that had refused to protest, rightfully or not.

I pulled into the Laudholm parking lot, which was abandoned, though there were signs of the recent crowds: cigarette butts, drifting candy wrappers, a baseball cap somebody had dropped. I picked the hat up and put it on a bench, then walked down to my usual path, which was muddy and trampled, evidence of a multitude of feet. There was the damp, pungent smell of disturbed earth. The narrow path had been violently widened by the crowds — grass, bushes, and saplings stepped on and broken. I walked beneath the overhanging branches, breathing deeply, and reminded myself that everything would grow back, that nature renews itself, given enough time. I reminded myself that anger is self-injury and interferes with clear thinking and effective action. Enough already, I warned myself; and it was enough. I was becoming somebody I didn’t recognize, somebody I didn’t like. There was reality, and then there was one’s chosen response to it.

I came into the main clearing, framed by leafing-out oaks and swaying white birches, and stood quietly at the edge. Wide tire tracks led from the entrance of the reserve into the open field. Grassy clods lay everywhere, dark earth exposed and moist with humidity.

Beneath a sullen sky, a solitary workman piled onto his truck the last planks that had been used for either a viewing stand or the platform where the president had made his speech about the importance of preserving wilderness with private donations. Many thick planks rested atop one another in the truck. I wondered how many trees had been sacrificed for this purpose and hoped the lumber would be reused. When the workman saw me watching, he flushed and said, “I didn’t vote for the guy.”

I was startled by his defensiveness and wondered if something in my attitude suggested disapproval. At a loss for how to respond, I asked, “You didn’t put it up alone, did you?”

“The other guys have left. This is the last of it.” He climbed into the truck bed and pulled the final plank onto the pile, then said, “I just want you to know that I did think about refusing the job, but somebody else would do it, and I needed the work.”

“How do you know I’m not a Bush supporter?”

He pointed to my T-shirt, which had a picture of jazz saxophonist John Coltrane. “I just figured that anybody who likes Coltrane doesn’t like Bush.”

“Coltrane cuts across all political lines, but you’re right about me,” I replied. I still wondered why he was telling me all of this. I realize now how guilty he felt. None of my friends voted for Bush, yet every single one of them, like me, experiences some guilt simply by virtue of being an American. We are a nation ripped apart, furious with each other, half of us racked with remorse, half of us drenched in smug certainty, nearly all of us wondering what went wrong.

“I had to do this,” the man said. “It’s my job.”

“Hey,” I told him, “you don’t owe me any apologies.”

He shook his head. Before getting into the cab of his truck to drive away, he turned to me and said, “I feel like I need to apologize to somebody.”