For a Catholic kid, there was nothing good about Good Friday. From dawn to dusk, we had to fast on toast and tea, and then, when we were good and starving, we had to choke down a bowl of my mom’s fish stew. We couldn’t cut loose or even watch TV. We were supposed to mope around looking glum. We spent the entire afternoon in church. Usually, my mom picked us up early at school and took us to the interfaith service at Trinity Episcopal, where they read the Passion. Afterward, we walked over to our church, Saint Agatha’s, for the Veneration of the Cross.

But this year my mom was sick in bed, so my father decreed that I would take my younger brother and sister, Sean and Mary, to afternoon services. My job was to pray for Mom’s recovery and make sure the others didn’t act like chimps in church. Dad gave me three bucks for the collection, then thought about it and took one back. “Don’t want to give the Protestants too much,” he said.

As we walked across the town square, Sean suggested we use the collection money to rustle up ice creams at Friendly’s. I pinged him in the forehead. “It’s Good Friday, numskull.”

At Trinity Episcopal, Monsignor Yates and a young woman minister from some other church greeted us. The monsignor was there to represent the Catholics at the interfaith service, and he had on his battle face. He looked like he had personally seen Jesus die. He nodded gravely and looked around for our mom. Then he did the math and said, “Aren’t you kids good to come out all by yourselves on the holy day.”

I shrugged and kicked my feet. I didn’t want to get into the “How’s your mom?” routine. I made a move to sit down, but there was some kind of donation box in front of us. I wasn’t sure if we were expected to kick in now or wait for the collection basket. Maybe there was no basket. Maybe Episcopalians got their cash up front. I didn’t want to look cheap — especially with the monsignor watching.

As I dug in my pocket for the money, Monsignor Yates tugged on my jacket sleeve and whispered, “Are you guys coming over to Saint Agatha’s later for the Veneration?”

I nodded and edged away. He smelled like the preservative we used in biology class.

“We’re short on altar boys. How about being a good kid and suiting up?”

Behind the monsignor, Sean flicked holy water into Mary’s face. “I’m supposed to watch my brother and sister,” I said.

“I’m sure they’ll be just fine.” He turned to them. “Won’t you be good kids for your brother?”

They nodded like alien pod people. The monsignor raised his shaggy white eyebrows at me.

“OK,” I said.

I handed Sean a dollar and made sure he dropped it into the box. I stuffed the other dollar in and took Mary’s hand. We ducked into the first empty pew.

The Passion was always read by high-school kids from various churches. Each kid read a different part. It was a pretty decent story if the narrator didn’t stink. This year she was a nerdy girl with monster glasses and great voice inflection. She sounded like a professional actress. Jesus, though, was played by some sorry goober with a hunchback and a nasal whine. During the torment in the Garden of Gethsemane he sounded like a spoiled brat trying to weasel his way out of doing chores. In fact, he sounded a lot like me when my dad asked me to do something around the house. And Dad usually just asked me to take out the garbage or mow the lawn, not hang on a cross for the weekend. I was glad Jesus had been Jesus and not some slug like me. Humanity would be in a sorry state if it had been on me to buck up and save everyone.

As I thought about Jesus trying to squirm out of his responsibilities, a funny feeling came over me. I had been praying to God for a year to make my mom better, but I could see now that God didn’t just do what you asked — not even when his own kid was crying and sweating blood. Someone had to pay the price. I wondered what I’d do if God asked me to pay the price for Mom. Could I give him the OK to take me instead? Wasn’t that what Jesus did?

Maybe I could do it. I pictured God appearing to my mom and telling her about my sacrifice. “Not many kids will do that for their mothers anymore,” God would say, nodding approvingly. Mom would look into my casket and lament not appreciating me more before my death. I imagined my classmates putting on a pageant about me. In the audience, my weeping parents would hug Sean and Mary as my character passed away.

Suddenly the Passion was over, and people were thumbing through hymnals. I wiped a tear from my eye. Sean was blowing bubbles with his spit. Mary eyed me suspiciously, then went back to picking a scab on her wrist.

After the interfaith service, we walked to Saint Agatha’s, where the Stations of the Cross had just finished. Most of the old-timers were filing back into the darkened church or waiting in the back for confession. I parked Sean and Mary in the pew closest to the altar and whispered, “Pray for Mom.” Mary knelt down and folded her hands, but Sean leaned his head back and stared vacantly at the paintings on the ceiling.

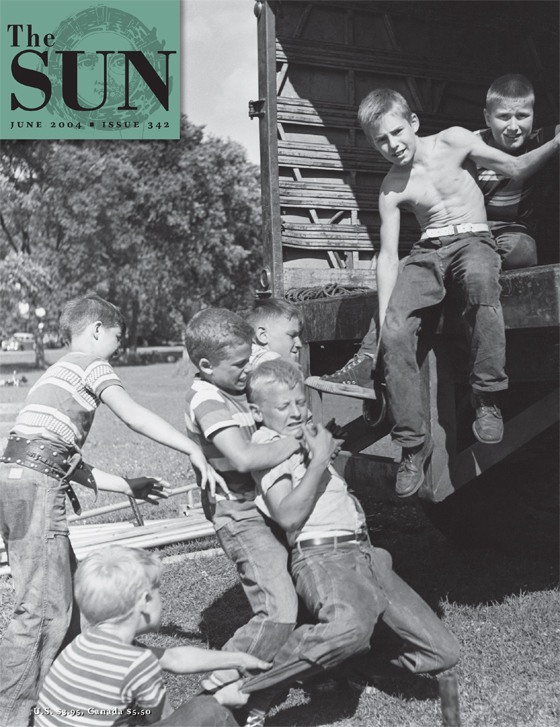

When I elbowed him, he lolled his head back and forth like Stevie Wonder. I twisted his wrist hard and put my mouth to his ear. “Hey, numbnuts,” I whispered, “how about thinking about Mom for a second here?”

“You’re hurting me,” he said.

“That’s right, dickhead. Mom’s got cancer, and you’re too lazy to say some prayers for her on Good Friday. Why don’t you think about that?” I genuflected, then crossed the nave to the altar boys’ room.

After suiting up, I sat on the confessional chair and tightened my shoelaces. I didn’t want to get to the sacristy too early, because the service was being done by Father Pham, our visiting Vietnamese priest. His full name was Father Pham Mihn Hua, but the altar boys called him “Farm Manure.” He could barely hack his way through Mass, so the monsignor usually just let him dish out Communion. The one sermon he had given sounded like a fight sequence from a karate movie.

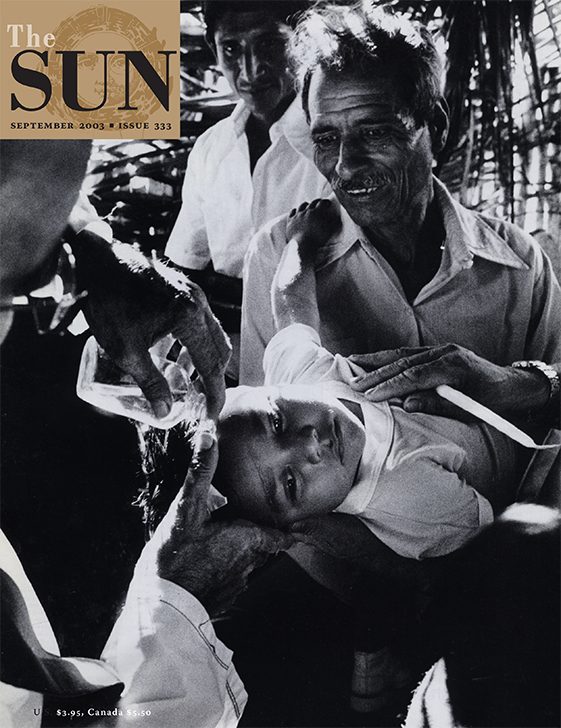

At a minute to three, I took the gloomy back passage around to the sacristy. Father Pham stood at the far door, peeking into the church. He came back with raised eyebrows and a smile. “We godda ladda pipple owdere.”

I coughed into my hand. I had never worked the Good Friday service. Some of it was like a mass, but there was chanting and a bizarre procession with a heavy wooden cross. It had to be carried a special way, and then people came up and touched it or maybe even kissed it. I began to sweat.

Father Pham adjusted my surplice, then slipped into a purple chasuble. When he turned to the vestry mirror, I crossed the room and cracked the door to the church. A shiver went through me. Not thirty feet away, my dad was guiding my mom into Sean and Mary’s pew. Mom was wearing her black bandanna. She grimaced as she sunk into her seat, then turned and smiled at Mrs. Fallon, who reached up and squeezed her shoulder.

My parents had been arguing all week about whether Mom could go to Holy Week services. My dad wanted her to stay home and receive the Anointing of the Sick.

My mom snorted. “Why don’t you just go ahead and plan my funeral?” she said.

Dad choked up. “That’s not . . . Look, it’s for anyone who’s sick, that’s all. I mean —”

“Try to have a little faith,” said my mom. “I’m not checking out anytime soon.”

“Of course not,” he lied. “No one’s saying that.”

Behind me, Father Pham said, “You know dah benarayshen ah dah coss?”

I swallowed. “I —”

“No plobrem. I ter you whena blinga dah coss, OK?”

I nodded tentatively. I had no idea what he was saying.

He ran his finger across something in the lectionary, speaking quietly to himself. When he was done, he snapped the book shut, and we bowed to the crucifix on the wall. “OK. Aftah dah leedings, we walka down dah back, up sayntah, stop sree time befah dah artah.”

I swallowed. “Three times including —”

“Yes. Sree time.”

“Total? Then do we —”

“Sree.” He held up three fingers.

He put the lectionary in my hands and pushed me out the door.

We processed past my family and onto the dimly lit altar, which had been stripped of everything but a single purple cloth. After I’d set the lectionary on the lectern, I took my place below the tabernacle. I watched my parents for a nod, but they seemed tired and distracted. When Mr. Sullivan came forward to lector, I opened my missalette, pretending to follow along but really flipping madly ahead to figure out what would happen next. I was dizzy with hunger and couldn’t seem to find the right service. By the time I realized I had the previous week’s missalette, Mr. Sullivan was lumbering back to his pew. The giant wooden cross loomed in the apse.

Father Pham rose and strode down the altar steps. I froze, not sure what to do, but at the low altar, he turned to me and jerked his head toward the cross. I hopped up and hoisted the cross, following him down the side aisle, past the hissing brown radiators. The cross was heavy, and I had to hold it high so it wouldn’t catch in my skirts. There was no music, only the shuffling and coughing of the hundred or so people present. Our neighbor Mr. O’Brien winked at me as I went by. I saw a couple of kids from school and quickly looked away, because they sometimes made me grin uncontrollably.

At the back of the church, Father Pham draped a purple cloth on the cross and shooed me up the center aisle. I processed solemnly, the way my dad had taught me. A third of the way to the altar, Pham tapped me, and I stopped. He turned me around so that we were face to face. He removed the cloth from part of the cross and motioned that I should lift it above my head. He spread his arms wide, closed his eyes, and took an enormous breath. A horrible, nasal wail came from his mouth. It drove me back a step, and I struggled to balance the cross.

I knew he was singing, “Behold the wood of the cross, on which hung the Savior of the world,” but it sounded like a baby seal being slaughtered. His nostrils flared with the effort. His jaw shook, and little flecks of spit shot past my head. I stared past his liver spots and big silver molars into the quivering red pit of his throat.

I started to laugh.

I pinched myself and directed my gaze at the carpet, but the terrible feeling grew. As the congregation sang its response, I turned back toward the altar, clenching my teeth, and told myself to knock it off.

Halfway up the aisle, Father Pham tapped me again and let fly with the wailing. His uvula danced at the back of his throat. I bit my lip, but a snort escaped. To my right, Mrs. Mack nudged Mr. Mack. They grinned at me. I looked down and pictured someone sliding a bamboo reed under my fingernails. I imagined having my penis sliced in half with a razor blade and my testicles fed through a meat grinder. But somehow that seemed even funnier than Pham’s wailing. Another snort huffed out my nose.

When we processed again, I walked faster, knotting my face and holding my breath. I became lightheaded and floated above the pews. I could see how funny it would be to fall to the mottled marble tiles and howl with laughter. Parishioners smiled and ribbed each other, hoping I would crack.

Pham stopped me just in front of the low altar. Uncontrollable gurgling noises came out of my nose as I tried to stifle my smile. My father leaned out into the aisle, looking like he had just murdered a man. He drew a finger across his throat and mouthed, “Cut it out.” Next to him, my mother stared solemnly at the floor.

The smile left my face. I turned to Father Pham and raised the cross. Mom is going to die, I told myself. Do not mock the Lord on the anniversary of his death.

Father Pham cut loose like a basset hound. Veins erupted from his temples. In my head a voice said, Houston, we have a problem.

I tried to imagine my mom receiving the last rites. I pictured us standing miserably around our sofa while the priest bent to anoint her forehead with chrism. But the priest became Father Pham. He bellowed into her face.

I closed my eyes, but it was too late. I snorted. Sharp hisses escaped from between my clenched teeth. When I opened my eyes, most of the congregation was laughing. They grabbed their guts and leaned on each other. They slapped the pews and wiped their eyes. I set the cross down, leaned on it for support, and let the laughter pour out of me.

Pham wound himself up for the big finale, punching out each word: “dah . . . . Saybya . . . ob . . . dah . . . wooooooooo.”

As I set the cross into its stand at the base of the low altar, the hysterical feeling suddenly slipped away.

Only when I had stepped behind one of the massive pillars at the side of the altar did I risk a glance at my family, whom I had just disgraced on the most serious day of the year, in the most serious year of my life. My father bent over my mother, who was doubled up and shaking. But she was not crying or shaking with anger. She was laughing. Sean and Mary watched her with surprised smiles. My father wiped a smirk off his face and lifted his eyes to the fresco above the high altar. He brought himself under control, but my mother didn’t even try. She sat back on the pew and let the laughter spill silently from her. Tears streamed down her face. When she caught my eye, she shook her head in the way that meant, You are a piece of work, buddy boy. Then the laughing fit took her again.

In front of the low altar, Father Pham continued the service, but I wasn’t paying attention. I was far away, remembering the last time my mother had belly-laughed like that: She was lying on the pine floor of a rented cottage on Cape Cod, crying with laughter, pounding the floorboards. None of us knew what was so funny, but the laughter infected us anyway. As soon as one fit subsided, another started, until we were all on the floor holding our sore bellies. It was miraculously sunny along the water that day. Sean and I had been swimming. We had caught a bucketful of fiddler crabs and set them free. We had all eaten fried clams and ice cream. We had played two rounds of miniature golf. Our laughter was part of a summer that stretched ahead of us with an endless beat: life is good, life is good, life is good.