I woke up this morning on the third planet from the sun. In the twenty-first century. In the United States of America. Outside, the sky was still dark, but at the flip of a switch the room was flooded with light. Amazing!

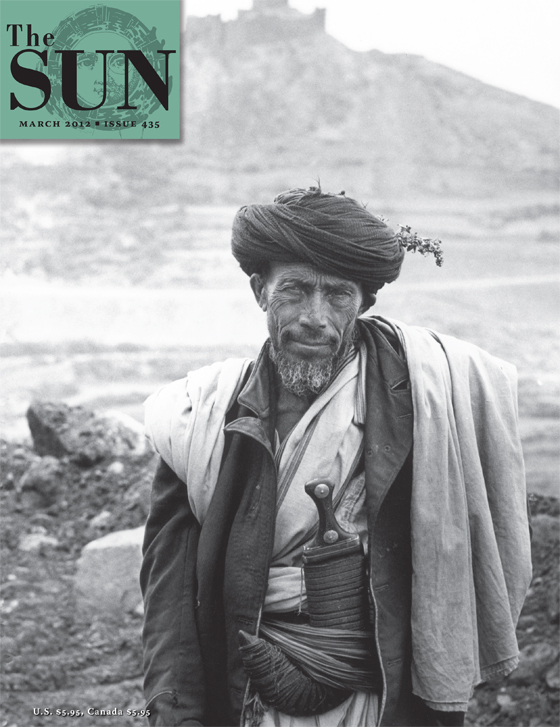

I turned on the radio: two more U.S. soldiers had been killed in Afghanistan. Now how amazing is that? More than ten years have passed since the 9/11 terrorist attacks. The leadership of al-Qaeda has been decimated. Osama bin Laden has been dispatched by an elite team of Navy SEALs. Yet the war in Afghanistan drags on. More than 1,700 U.S. soldiers have died there. More than 15,000 have been wounded. Thousands of Taliban fighters and tens of thousands of Afghan civilians have been killed. “Operation Enduring Freedom,” military officials call it. Operation Enduring Heartache is what it’s become.

How odd to be a citizen of the most powerful nation on earth, a country that, with only 5 percent of the world’s population, spends almost as much on defense as the rest of the world combined; a superpower that’s gone to war so often during my lifetime — Korea, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Grenada, Panama, Iraq, Bosnia, Afghanistan, Iraq again — you’d think it’s a habit we can’t break.

My desk is a mess. The world is a mess. Yes, we all could have done better: all the letters answered; all the dead from all the wars buried before the bodies start piling up again.

Maybe I expect too much from my country. After all, America, you’re only 235 years old. As empires go, you’re still wet behind the ears: too much of an adolescent to stop going to war every fifteen minutes; too sullen to admit when you’re wrong; unwilling to walk a mile in someone else’s moccasins because you’re too lazy to pull over and get out of the car. How much weight did you lose on that last diet? That’s what I thought. How many times have we begged you to confess that it was you who tortured the neighbors’ pets? Each time, you shake your head and insist you’ve never tortured anyone.

“Everyone believes in the atrocities of the enemy,” the novelist and journalist George Orwell wrote, “and disbelieves in those of his own side.”

Occasionally a Sun READER criticizes us for publishing the work of too many prisoners in Readers Write. But the section isn’t called “Virtuous Readers Write” or “Nonviolent, Nurturing Readers Who Are Without Sin Write.” If we rejected a submission because the author is in prison, we’d be emulating a penal system that not only deprives convicts of their freedom but also denies their basic dignity. As far as I can tell, Jesus’s injunction to love one another didn’t come with qualifications about a person’s criminal record or, for that matter, the so-called lesser offenses for which we’re never prosecuted.

Imagine a litmus test for everyone who submits writing to The Sun: how many times they’ve lied to a spouse; whether, in their most recent trip to the mall, they remembered Gandhi’s advice to “think of the poorest person you have ever seen and ask if your next act will be of any use to him.” Changing the prison system — changing any institution — can seem like an impossible challenge. But there’s nothing impossible about changing the way we relate to a single prisoner.

Many years ago I bought a used car from a man who’d served time in one of the country’s most brutal prisons. He told me about convicts being given one roll of toilet paper a month and one bucket of water a week for a “shower.” He described white guards who assaulted African American inmates with their batons, which they called “nigger sticks.” If his teenage son ever broke the law and was going to be sent to prison, he said, he’d kill him first. It would be more merciful.

Saint James Harris Wood, a writer whose work we’ve published, is in prison in California for armed robbery. “Every morning before breakfast,” he wrote to me recently, “there’s a flock of hundreds of starlings that fly over the yard in crazy wheeling circles, like a school of fish, making strange patterns, splitting into separate little flocks and rejoining and splitting up again, and I can’t understand why they don’t run into each other. I could watch them for hours, but they only do it for about ten minutes, every single morning. It’s weird. Why would they want to be in prison?”

I dreamt that I was an FBI agent assigned to keep tabs on a racist, charismatic right-wing zealot. I showed up undercover at one of his rallies, but once he started speaking, my dismayed expression must have given me away. His henchmen surrounded me and started to beat me up. I managed to get away and call for reinforcements. That’s when I woke up.

I remember the leader’s blond hair and blue eyes, his penetrating gaze, his disconcerting self-assurance — as convincing an antichrist as one could imagine. And there I was, arrayed against the forces of evil. And I ran. But I didn’t turn in my badge and my gun and ask for a desk job. I ran to get help and return to the struggle.

I need to remember this the next time I’m tempted to judge those who use force to deal with real or imagined threats. Whether they’re FBI agents or Navy SEALs or cops on the street, don’t most of them believe they’re serving the common good? Don’t they deserve some acknowledgment of that, even if I disagree with their politics or suspect that their actions often create, rather than relieve, suffering? In their dreams, too, they’re chasing the bad guys or being chased by them. In their dreams, too, the pinwheel eyes of the megalomaniacal antichrist are spinning like crazy.