My daughter, Anya, is five and a half. We are on the subway. She’s looking out the window at the dark contours of the tunnel and her own reflection in the glass. I’m thinking about Bill, an old acquaintance. His face comes to mind with a strange vividness, like in a dream.

The train emerges from the tunnel onto the Manhattan Bridge. Look at that view, I say to Anya. Isn’t it amazing?

But she doesn’t want to talk about the view.

What would happen to the people if the train fell in the water? she wants to know.

That would never happen, I say.

But what if it did?

They would drown, I say.

The sun has sunk below the horizon, but the sky is still light behind the buildings of downtown Manhattan. A ferry slowly plows the silver-blue surface of the river.

Does drown mean die in the water? she asks.

Yes, I say.

What if I drowned?

That will never happen, I say.

But what if it did?

I would be the saddest man in the whole world.

She smiles mischievously.

You could never get another girl like me, right?

That’s right, I say, and I put my arm around her as the train goes underground again.

I met Bill through my ex-girlfriend Becky. They had been in the same screenwriting class and had started dating. He was the most talented writer in the class, she said. He had so many ideas.

Becky and I had been together for a couple of years in college. Once, we’d taken a Greyhound bus through the South, stopping in Tennessee to see her grandfather, a Southern Jew, which had sounded to me like an oxymoron but apparently wasn’t. He came to pick us up at the bus station in a super-long car, a Buick or Cadillac, that made him appear tiny behind the steering wheel.

We stayed one night at his house. He was in his eighties and maybe a little demented, and he wouldn’t stop talking. It took him half an hour to explain all the functions on the television remote. Becky and I looked at each other, trying not to burst out laughing. Old people were like another species.

We rode the bus on through Georgia, cracking the window to smoke cigarettes in the middle of the night when all the other passengers were asleep. We circled around to South Carolina and ended up in Myrtle Beach, where I saw the Atlantic Ocean for the first time. It was cold, and most of the restaurants and motels were closed. We sat on the beach, drinking wine and shivering.

Once, when we were in college, Becky’s father came to visit. He was Israeli, and she hadn’t seen him in years, though they’d been close when she was a kid. They both had an eye for the little things, she said. They would walk around Manhattan hand in hand, looking closely at the world. But when she was ten or eleven, he moved back to Jerusalem, and after that she hardly ever saw him.

I met him at the house she shared with two roommates. He was tall and had a long beard. I knew from Becky that he was a professor. We talked about Ulysses, which I was reading for a class.

We all sat around the dingy living room smoking weed — I had never smoked weed with someone’s dad before — and then he called a friend in Berkeley. I’m with my daughter and her neo-pagan friends, he said and laughed. I thought he was maybe the coolest person I had ever met. Like me, he was the descendent of German Jews, and I told him about my grandfather’s experience during the Second World War. I didn’t know a lot, mostly just the names of the camps where he had been a prisoner: Dachau, Buchenwald, Auschwitz. We talked about Judaism. I said I wasn’t religious, and he asked what I meant.

I said, I don’t believe in God. I don’t have faith.

He said, Everyone has faith.

Not me, I said.

But every moment is an act of faith, he said. You have faith you’re alive, no? You have faith you’re sitting here having a conversation with me. That I’m listening to you. Or maybe you don’t. Maybe you believe none of this is real. Maybe you believe in nothing but an endless void. But that’s still a kind of faith.

In the morning, Becky and I took him to the diner where we always went on the weekend. We ate eggs and toast and bacon and smoked cigarettes while the waitress came around to fill our coffee. The waitress’s name was Sara. She and I had a class together. She was beautiful and slightly aloof. She wore a tight black miniskirt and a yellow T-shirt with the diner’s name on it. Her long hair was dyed red.

Becky’s father left that afternoon, and I never saw him again. A couple of years later he got sick and had to have his arm amputated. Becky and I had broken up by then, and I was with Sara. When I heard that he had died, I called her right away and left a message saying how sorry I was. I told her to call me if she wanted to talk, but she didn’t.

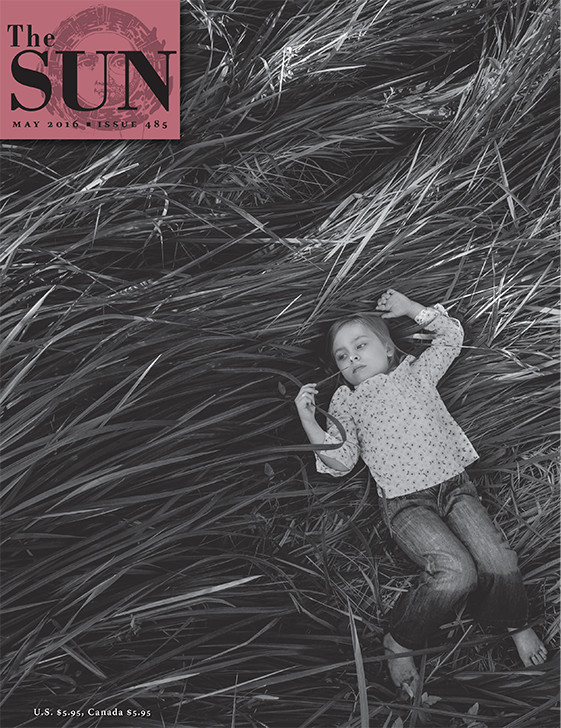

I’m lying next to my daughter in the dark, rubbing her back as she goes to sleep.

Daddy, I have a question, she says.

What, sweetie?

Can I come to your funeral?

I chuckle. Sure, I say.

Will your funeral be just your family or your friends, too? she asks.

I think both, I say.

I want my funeral to be everyone I love, so no one is left out and feels bad, she says.

That’s nice of you, I say. But let’s go to sleep now.

I remember when I first became preoccupied with death. I was a little older than my daughter is now. My parents were splitting up, and my mom was moving out. I went over to a friend’s house for the night, but I couldn’t fall asleep. I felt so weak, so defective. My friend was a normal kid, and I was not.

I lay awake at my friend’s house, thinking about my father. I could picture his face so clearly. In the day he was the man who took care of me, but when I was away from him at night, he seemed small and helpless. I was terrified that he was about to die. I could see darkness curling over him like a wave. When I couldn’t bear it anymore, I got up and went downstairs and called him on the phone. His voice was groggy with sleep as he tried to talk me down, reading me a story to soothe me, but it didn’t work. Eventually he got out of bed and came to pick me up. As soon as I was in his car, I could relax. He was safe; I was safe. I wasn’t afraid anymore.

This happened more than once.

Years later, when I was a teenager, I was snooping around in his desk and found a small blue diary from the time when he and my mother were separated. I opened it and read a few grief-stricken sentences about his wish to die. Immediately I put the book back in the drawer, never wanting to see it again.

Suicide runs in my father’s family: both his grandfathers, his uncle, and his father all killed themselves.

I was twenty-five when my grandfather said he was planning to end his life. Nobody could talk him out of it. I took the train to Chicago to see him one last time and say goodbye. He was lying in bed, staring up at the ceiling. I will carry you inside me, I said.

Don’t carry too much, he said. Be yourself.

My sense of who I am begins with the Holocaust, my father wrote to me once in an e-mail. He was born three years after my grandfather’s liberation. Growing up, my father tried very hard to be good and to please his father, who poured his hopes for a new beginning into his only son.

After my parents split up and my mother left, I had daydreams of my father screaming. The daydreams didn’t stop even after my mother came back a year later. I would be walking home from the schoolyard, where I’d been playing with my friends. Everything would be quiet except for the sound of the basketball I was dribbling, and then suddenly I would picture him screaming. A frantic feeling would fill me, and the hair on my arms would stand up. I’d want to run away, but how could I run away from a scream that was inside of me?

After college I moved to New York to be with Sara. We lived together for a time, and then we broke up, and I got another apartment. I needed to be on my own, I thought. I wasn’t ready to make a commitment.

But I couldn’t stay away from her entirely. We’d meet up and go to art galleries and movies and sit in bars in the late afternoon, drinking beer and playing chess. She was working in a homeless shelter on the East Side and just beginning to think about a career in clinical psychology; I was trying to write and teaching GED classes to inmates on Rikers Island, where I felt strangely at home.

Sara accepted me completely in a way no one ever had before. But deep down my ambivalence about the relationship didn’t go away.

Before bed she would sit by the chair next to her window, surrounded by six or seven spider plants of various sizes, and smoke her one cigarette of the day. I would smoke either a pack or nothing — I didn’t know how to be moderate.

On the weekends I was doing a lot of cocaine. If life was random and purposeless, I thought, why not try to experience as much pleasure as I could? There was a bar in Williamsburg with a curtained-off space in one corner where you could do drugs. The bar had salsa bands and cheap beer, and it stayed open from Thursday afternoon to Sunday morning without closing.

After long hours in that dark, windowless place, chasing a high that was becoming harder to catch, I’d step out into a bleak Sunday dawn and walk over to the waterfront, a couple of blocks away — jagged rocks, abandoned factories, piers half sunk into the river. Looking at the light sparkling on the water, I’d do the rest of my cocaine.

I had been in New York for two years when Becky and I got back in touch through a mutual friend. She was living with Bill not too far from the apartment where Sara and I had recently moved. We were back together again.

The first time I met Bill was at a bar on Houston Street. He was five or six years younger than me and seemed like a kid. I was only twenty-five myself, but I felt old. He had a bright, wounded smile. I liked him immediately: his openness, his lack of arrogance and pretension. He wore a yellow trucker hat, his hair sticking out at the sides, and a red-and-black flannel shirt that reminded me of a jacket my dad used to wear.

We talked about poetry: Rimbaud and Frank O’Hara. One of Bill’s teachers had told him to read poems out loud, breathing after each line. He’d never appreciated poetry until he started doing that.

He said he’d published some poems in a magazine, and I was jealous. I hadn’t published anything. But I still enjoyed being around him.

We got drunk and talked about music. He liked Bright Eyes, a band I’d never heard before. Becky was the same as always — funny, anxious, warm.

You guys remind me of each other, she said, and I remember feeling flattered: she had gone out and found another me. That’s how I thought about it.

Afterward we saw each other frequently. Sometimes Sara would come, too, but she was a little uncomfortable when the four of us were together, so more often I went alone.

One time I gave Becky and Bill a short story I had written and was proud of. A couple of weeks later we went out for a drink. Becky said she liked it, but I could tell she didn’t. I pressed her for more, and she said sometimes it seemed like I was trying too hard.

Bill didn’t really have much to say. He thought the dialogue was funny.

After a while we left the bar and went back to their apartment, which was in disarray — clothes and dishes everywhere. I had forgotten what a mess Becky could make of a room. We smoked some weed. Bill put his arms inside his T-shirt and sat in a chair in the corner. Becky cast annoyed glances at him. I saw their eyes meet, communicating something I didn’t understand, and I suddenly felt alone. What was I doing there? I had no place in her life anymore. For a moment I saw myself through Bill’s eyes: the ex who couldn’t let go. He was mumbling and laughing quietly. His arms were still inside his shirt, as if he was restraining himself. I imagined Bill and Becky arguing as soon as I left: Why did you have to invite that asshole here? he would say. You were the one who invited him, she would reply.

Well, I should probably get going, I said.

Thanks for coming by, Becky said, and we hugged. Bill slid his arm out of his shirt to shake my hand. It was fun, he said, smiling and looking away.

My daughter and I are sitting on the couch, reading The Gods and Goddesses of Olympus. She wants to read it again and again. It is a warm summer night. Unintelligible voices rise up from the street below. I hear a siren in the distance, getting closer and then farther away.

I put the book down.

Daddy, will you always love me? she asks.

Of course. You know that.

But that’s not true, she says, smiling as if she’s caught on to how it actually works.

What do you mean it’s not true? I say, trying to match the casualness of her tone.

Not when you’re dead and I’m dead. Then you won’t.

How do you know?

I want you to live for more than eight hundred years, she says. I want you to live forever.

I’m going to live for a long time, I say. Don’t worry.

After Becky and Bill broke up, they remained close friends. I ran into her one day on the street in Brooklyn, and we went to the Tea Lounge, a dim, cavernous space with lots of tables and old couches. All around us were mothers and their babies. I asked how Bill was doing.

He’s a mess, she said. I get depressed whenever I talk to him. He’s doing drugs. He’s full of anger.

Her new boyfriend was a comedian, and they were moving to Los Angeles in less than a week. She was going to go to film school there.

What about you? she asked. I heard you were like Mr. Super Jew now.

I laughed. Not really, I said, but I have been going to synagogue.

Crazy, she said. I can’t picture you there.

I tried to explain what had happened:

I was with Sara in Cape Cod for a friend’s wedding on the beach. We’d been talking about getting married ourselves, but I wasn’t ready. I didn’t want to be constrained. I didn’t want to bow to convention. My resistance felt to me like a form of nobility, but Sara’s patience was running thin.

At the start of the ceremony my friend came walking down the sand wearing a white suit. He had tears in his eyes. He looked so strong and determined, so full of love.

While I stood watching my friend get married, a terrible feeling seized me: that my friend was blessed, and I was not. A part of me always wanted to run from anyone who got too close. How could I ever do what my friend was doing now?

I’d been taking medicine to treat my gnarled toenails, which were yellow and black. (Becky laughed when I told her this.) I wasn’t supposed to drink while I was on the medication, but that didn’t stop me, and that night at the reception, I got very drunk. Sara went back to our room while I kept drinking, trying to dispel the bad feeling that had stuck with me since the ceremony.

The next morning we were supposed to go to a brunch to celebrate the wedding, but there was no way I could make it. I had never been so sick, and I just wanted to go home. We got in the car and started to drive, but a few miles down the highway, we had to stop, because I was too sick.

Let me be alone, I said, and Sara got out of the car.

I watched her walk away.

I was sure some sort of poison was running through me. I leaned against the window and saw my face in the side mirror. My eyes looked so sad. I was twenty-nine years old, and I wanted to die.

Powerless and afraid, I called out, Help me, God. Please help me.

And suddenly there was this warm, clear light all around me, and I had the sensation of being lifted into it. The experience lasted only a few seconds. My eyes burning with tears, I looked up and saw Sara walking back to the car, the Atlantic Ocean behind her, and these words came to me: For the terrible pain of being alive, I give you love.

After I told Becky this story, we were quiet. I sipped my chocolate tea, feeling exposed. Maybe I’d said too much. For some reason, I thought she was going to make a joke about it.

What was that light? she asked.

It was like the light you see behind your eyelids if you look at the sun with your eyes closed, I said.

Maybe that’s all it was, she said.

Except I could feel it, I said. It had a presence. Like it was there for me in the deepest way.

That’s amazing, she said.

Then we said goodbye, and I wished her luck at film school. I haven’t talked to her since.

Instead of driving home, Sara and I got a motel room and walked to a river. Light shone on the surface of the water, and the moon rose above a bridge. I felt an inexplicable force moving through me. I was alive, and I was with the woman I loved. I could see that I had been holding myself back from her, but I didn’t want to do that anymore. I kept kissing her hand. I hope you’re not going crazy, she said. She put her arm around me, pulled me toward her, and pressed her face against my cheek.

Back in New York, I started going to synagogue for the first time in my life. I wanted to stay close to that benevolent presence if I could. Sara was a little baffled, but she wasn’t opposed to my new interest in religion. She could sense that I had changed, and we were happier.

Going to synagogue felt like a small thing I could do to honor my family’s history. My grandfather had spent five and a half years in concentration camps, and his mother had been murdered in a camp. He’d found no comfort in Judaism, but when I heard the cantor’s voice, I felt gratitude for the mysterious love I had been given.

The following summer Sara and I were married on a barge in Brooklyn. It was a joyful ceremony. My ancestors seemed very close — all the dead whose lives were intertwined with our own. The rabbi gave her blessing, and I raised my foot and broke the glass.

When Anya was born, her first sounds were like a goat’s bleating, and I heard myself laughing and crying at the same time.

She had the tiniest hands.

Anya was the first baby I’d ever held. I’d always been afraid I might drop them or damage them in some way. I sat in a chair, and Sara laid our daughter in my arms. She weighed almost nine pounds. I looked down into her ink-black, ageless eyes, which were unfathomable, like the eyes of a strange animal.

Her head rested on the crook of my elbow. Her body, warm with life, was pressed against my chest. I closed my eyes and held her against me.

The last time I saw Bill was at a Yo La Tengo concert down in Battery Park. He was all alone and walking toward me when our eyes met. I stopped to chat, but he just nodded and kept on walking, disappearing into the crowd.

One weekend Sara and Anya went upstate to be with Sara’s parents while I spent a whole day in our apartment working on a story. The more I worked on it, the worse it got. By evening I just wanted to get drunk. At a bar in my neighborhood, I bumped into someone I hadn’t seen since college, a woman who’d known both me and Becky. I asked if they still kept in touch, and she said she’d seen Becky five or six months ago, when she’d flown in from the West Coast for a funeral.

Who died? I asked.

She told me Bill had hanged himself.

He was twenty-eight years old. Once, he gave me a handmade book of his poems, but I misplaced it during a move. I still can’t find it.

Anya and I are walking to her new school. It’s the second day of class. She wears her new backpack, which looks so big on her small body. We walk along Caton Avenue, her hand in mine.

Yesterday, when Sara dropped her off, Anya didn’t want to say goodbye, and she was crying when she went into the building.

Are you going to teach today? she asks me.

I’m writing, I say. I’m working on an essay. You’re in it.

She smiles. What’s it about?

It’s about faith.

What’s faith? she asks.

I don’t know how to answer.

Last night I stepped outside and looked up at the sky. Despite the streetlights, I could see some scattered stars. When I was a child, spending the night away from my father, I was terrified of the dark, because its vastness seemed to hold only the promise of annihilation. The terror never really left me until that moment in the car on Cape Cod, when I realized there was more. I could let myself fall, and something would hold me.

But now, as I think this, I wonder: The light that came to me in the car — was it even real?

Faith is like trust, I say to my daughter. It’s trusting in something, even though you don’t know.

We turn down the street her school is on. She stops to look at a bright-yellow leaf on the sidewalk, one of the first of autumn.

Let’s go, I say. Let’s not be late.

Anya picks up the leaf and gives it to me, and I put it in my pocket.

We go through the gate into the schoolyard, where the children are all lining up, and I wait with her in line. The brick building looms against the sky. The line starts to move, and she grabs on to me. I hug her tight. I can feel her heart beating. I tell her I’ll be waiting for her when she comes out, and then I let her go.