As a Lesbian Avenger in San Francisco in the late nineties, I wore a lioness crew cut and crusaded against gender stereotypes. Still I believed fervently in femaleness; the word woman encompassed sisters, lovers, and self. Some nights I read Adrienne Rich’s poetry out loud and longed for a partner about whom I could declare, “We were two lovers of one gender, / we were two women of one generation.” When I met Sarian, I thought she might be the one.

Sarian found her way to our Avengers group in the middle of her law-school finals. Fed up with stuffy Stanford University, she came to a Monday-night meeting in my cavernous living room. Social workers, Starbucks baristas, dot-com engineers, preschool teachers, and sex-toy saleswomen sprawled on the salvaged couch and vinyl chairs, a flock of dykes clad in pink nail polish and torn fishnets, studded belts and fleece jackets. A few friends and I had revived this San Francisco chapter of the Avengers, and I sometimes still worried that a pack of Harley-riding butches would storm a meeting and challenge our presumption. I was a former good girl who had shed her long brown hair and habit of looking up to men only two years earlier.

Sarian came to my door in shorts, slouching but not shivering in the December night. She looked as slim and agile as a monkey and slightly aggressive with her bleached, spiky hair. I liked the name “Sarian” — it sounded slinky, sylvan, prehistoric. She followed me upstairs, where the Avengers were discussing their favorite superheroes and the things they wanted to change about San Francisco. I hoped Sarian wouldn’t be disappointed, as the wish list couldn’t have been described as practical. The mantra was “dyke space in the city,” but I didn’t see how we could acquire this unless an heiress donated a Victorian. Clad in black with a shaved head, my co-organizer, Sam, pounded the air with her fist and announced, “We’re here to fuck shit up!” Another Avenger looked forward to the naked-pudding-wrestling fundraiser. Finally someone came clean: a sweet-faced college kid said she just wanted a girlfriend. Nervous laughter ensued; almost all of us were single.

The original Lesbian Avengers, started in New York City in 1991 by writer and Act Up veteran Sarah Schulman and five other women, did more than matchmake. After skinheads threw a Molotov cocktail into an Oregon house and killed a lesbian and a gay man, the Avengers publicly ate fire in protest, chanting, “The fire will not consume us. We take it and make it our own.” Schulman seeded Avengers chapters around the country and adopted the slogan “We recruit!” to provoke the Christian Right. The D.C. chapter set up a “lesbian lifestyle” table at a Family Research Council convention, and an earlier San Francisco chapter stormed the offices of Exodus International, a Christian group promoting “freedom from homosexuality.” The Avengers released bags of locusts at the front desk, whereupon the receptionist called 911 to report, “There are lesbians here with bugs!”

Our incarnation borrowed the Avengers’ bomb logo and mission statement, which called on queer women to fight for “issues vital to our survival and visibility.” Sam even taught us to eat fire off coat hangers, though I only closed my teeth around a microscopic shred of flaming cotton.

Sarian arrived just as the chapter hit upon a cause: a local church had set up a homeless shelter for queer youth, but some neighbors were attempting to shut it down. The Avengers had met with city supervisors and started a petition to save the shelter. To my delight, Sarian volunteered to canvass. A few nights later, as she and I taped up flyers, I learned that she had ditched a budding career as an academic to try her hand at activism. Here was a smart-cookie queer, just what I aspired to be. We accosted passersby with our spiel about gay youths kicked out by their parents, and Sarian walked right into a taquería to gather signatures. I was too shy to follow, but I watched as she bent to talk to an older man in a jean jacket. Sarian waited, grave as a butler, gangly arms at her sides, while he signed. She looked vulnerable yet determined in her baggy shorts. I was hooked.

Each time the Avengers planned an event, I’d wonder: Would Sarian show up at the decorating party for “Dyke Day in the Castro”? Would Sarian join the stealth-stickering operation at Victoria’s Secret? Sarian would; Sarian did. As a way to build up my sexual courage, I figured I’d better ask her out. I left on her answering machine what I hoped was a sufficiently blasé invitation to do something together. Sarian called right back: sure, what did I want to do?

Sitting in a sushi dive known as “No Name,” because it had no sign, we talked as if starved for speech. The waitress had to return twice to get our order. It seemed Sarian and I had led parallel lives: She had a ba in math; in high school I’d planned to major in math. Each of us had embraced philosophy and then turned away because it wasn’t taught as if it mattered. We were both addicted to critical theory but tired of its self-referential obscurity. Sarian had spent the previous summer hiking the Sierras and the Santa Cruz Mountains — my favorite form of recreation. She was goofy and batted the air with her hands when excited; at family dinners I was wont to wear my spaghetti.

Stanford University was holding a formal dance that night, and Sarian half joked that we should drop by there in suits. I had always wanted to do drag, so we drove back to her studio and examined her collection of secondhand men’s clothes. I emerged from the bathroom in loose gray pants and a black jacket and eyed the Dickensian boy in the mirror. Dapper in a navy blue suit, Sarian ushered me out the door. The dimly lit hall at Stanford recalled my high-school homecoming, down to the cheddar potato chips and Safeway soda. The women wore poofy dresses with low-cut tops, and the men stood around, as expressionless as lampposts. Few people talked to us. I felt like a spy.

Even when not in drag, Sarian and I shared a similar androgynous style. I hoped that together we could puzzle out the mystery of gender, a topic that increasingly took center stage at Avengers meetings. Our group had its roots in lesbian feminism, which meant we hated rapists, fat phobia, and any threat to women’s sexuality and solidarity. The scene in San Francisco was changing, however. The era of the flannel-shirted “tea and cats” lesbians had ended, and butch and femme roles had made a comeback after decades of feminist disapproval. Academics raved about postmodern theorists like Michel Foucault and Judith Butler, who questioned the foundations of gender. At the same time, female-to-male and male-to-female transsexuals were asking for recognition in gay and lesbian circles. The younger generation saw gender transgression as the common link among all these groups. “Queers” could help each other wriggle out of our Tarzan/Jane straitjackets.

By the time I moved to San Francisco after graduation, most queer organizations had added the T — for “transgender” — to their acronyms. Dykes and gay men danced at “Trannyshack” on Tuesday nights and preached transgender rights in public high schools. Two male-to-female trans women joined the Avengers: punk, sexy Susanna, who smoothed pancake over her stubble; and anarchist Chris, who looked like a plump boy but wore tight, glittery shirts. I referred to them both as “she,” as did everyone else. The Avengers brought in a consultant to teach us “Trans 101 for Revolution” and petitioned the local women’s bathhouse to welcome trans women. Yet when somebody’s male friend showed up at a meeting, we gently let him know it was a “woman-only space.”

I didn’t want to admit it, but inside my mind the biological binary still reigned. My father and my college buddies and my villainous ex-boyfriends were men, and I was a woman, as were most of my friends and all of my potential lovers. I thought of our group as a band of females with a couple of trans people thrown in for good measure. Once, I walked into a meeting just as Susanna lifted her shirt to display her new piercings. Her pink nipples jutted out of smooth, pale breasts, like a young girl’s. I had never tried to imagine her chest or inquired about the effects of estrogen. Transgender bodies seemed as mythical to me as dragon flesh.

After our night of drag, Sarian and I began to date. Maybe. I couldn’t tell. At the end of our evenings together she gave me long goodbye hugs, and her eyes darted all over me as she pulled away. During Avengers meetings I glanced at her sitting with her legs spread wide in tweed shorts. I allowed myself to imagine a kiss.

Sarian offered to teach me jujitsu, and one afternoon, during a lesson on a beach south of the city, I threw her down, pressed myself into her wiry frame, and pinned her hands while she wriggled. After a few more throws, we left off the instruction and began to bury our legs in the sand and unearth them. Then we thumb-wrestled. Our fingers wandered, gritty with sand, tracing the lines on each other’s palms.

A week later I acted. Sarian came to my place for tea, and as we perused my books, my arm snuck around her shoulder. Our lips met, and we tumbled onto the futon, where something verging on sex took place.

Afterward I said, “You can stay if you like.”

“That’s sweet.” She stared at me with those owl eyes. “I think I’d better get going.”

Two days passed without word from Sarian. I sobbed. I wrote poetry. On the third day, she e-mailed:

hey Anna —

do you want to talk sometime? i guess this might be hard timing-wise — maybe i could come meet you somewhere during your lunch on Fri? what do you think???

— Sarian

Sarian showed up at the waterfall in Yerba Buena Gardens twenty minutes late and declared, without preamble, “I was hoping we could just be friends. I don’t know why, but it doesn’t feel right.” Later she apologized and explained, “I was flirting with you, but when I flirt, I don’t yet know if I want to go further.”

For the next few months I rehashed the postmortem with my mother, my aunt, my straight college friends — anyone who’d listen. Sarian had seemed my best chance at a sister soul mate. Technically we remained friends, but over the summer she rarely attended our dwindling Avengers meetings. Someone mentioned that Sarian — who had changed her name once already when she’d invented “Sarian” — was changing her name again, to Daniel. Maybe she was constitutionally fickle. Then she e-mailed:

hey Anna —

do you want to meet sometime and do something?

— Sarian (changed my name though) ;)

A day later she sent this:

hey —

i wanted to tell you something — but not over e-mail — so if you have time sometime that would be cool. if not, i’ll attempt an e-mail version.

take care :)

I wondered if she had a deeper apology to deliver. It was even possible she had reconsidered. I remarked to my gossip-queen office-mate, “Sarian’s changing her name to Daniel, and she wants to tell me something in person.”

“I bet she wants to be a man!”

I scoffed. Sarian didn’t even consider herself butch. I’d read her term paper on transgender law and knew her reservations about sex changes. I thought of her lying topless on my bed: the apricot tint of her skin; her pretty breasts.

On a sunny afternoon in Dolores Park, I looked out over the bay and waited for Sarian. Gay guys in Speedos oiled themselves. A Latino man pushed an ice-cream cart up the hill. A few cotton-puff clouds hovered above the old mission and the palm trees. Up rode Sarian in a neon orange snow jacket, the kind I had worn as a kid. She hopped off her bike and hugged me.

“So you decided to change your name?” I said. I already missed the melody of “Sarian.”

“Uh-huh.”

I picked at the grass and forced myself to ask, “Why did you choose a male name?”

She breathed out, almost a whistle. “That’s what I wanted to talk to you about.”

I played the role of supportive friend, but my eyes kept returning to the lawn. Sarian/Daniel had realized over the last month or so that she wanted to “transition.” She was happy; she had no doubts. She had scheduled a meeting with a therapist. Four sessions would certify her to receive hormones, and then — she clapped her hands — she would get “top surgery,” maybe even fold it into her student loans. She had started going to a support group and had a crush on another “trannyboy.”

This last part made me freeze. “So, will you be gay now?” I asked. “I mean, will you be a gay man?”

Sarian/Daniel squinted. Her voice got quiet, as if she were explaining a simple but adult truth: “I guess I’ll just be queer.”

I swore in rhythm with my steps as I marched home. A man, for God’s sake. There were certain guys I loved and wanted to keep as friends, but the category as a whole was anything but appealing. Why would anyone consciously choose a role that throughout history had encouraged insensitivity and aggression? How could Sarian have decided this without having consulted any of the people who might love her? I made it home, plopped onto my futon, and pressed my teary face into a pillow.

I was hardly alone in my reaction. Many lesbians felt outraged and saddened by what they saw as female-to-male “defectors.” The Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, the most prominent lesbian gathering in the nation, excluded trans men. The Avengers considered this position intolerant, yet I had always sympathized with it a wee bit.

Soon after that day in the park, I agreed to accompany Daniel to the Nu2U thrift store. We became locked in a debate in the boys’ department, and I told Daniel that, deep down, I suspected that some lesbians were choosing masculinity because it was more prestigious than femininity. “Can you really say it has nothing to do with misogyny? Even unconsciously? At least for some trans men?”

“That could be,” he said (I was struggling to think of him as “he” now), “but it’s not my sense from the people I’ve met. I don’t think it’s the reason for me. I’ve done some soul-searching, and it doesn’t feel that way. There’s this intuition.”

Daniel held up some corduroys and raised his eyebrows for my opinion. He still called himself a feminist and hadn’t forgotten his dissertation on feminist philosophies of the body. How could I accuse him?

At least the female-to-male transition relieved me of my crush. Daniel inspired no angst-filled longing in me. I didn’t memorize his outfits or find myself brushing against him when we walked together. My friends assumed that his new identity explained his lack of interest in me; he had said that he liked “boyish” people no matter their biology, and even with a crew cut and cargo pants, I had never made it to boyish.

Daniel e-mailed me updates:

I just came back from my second waddell clinic appt and so I’m a bit bouncy. My next appt is on the 29th, and I might actually get T then. Wow.

Did he expect me to join him in fetishizing testosterone? Still, his mischievous tone charmed me. I warmed to stories of his transition “littermates,” a gardener and an environmental activist who met at Daniel’s studio to administer injections of “T” together. Tales of their hikes, wrestling matches, and stuffed-animal exchanges began to make his sex change seem less alien.

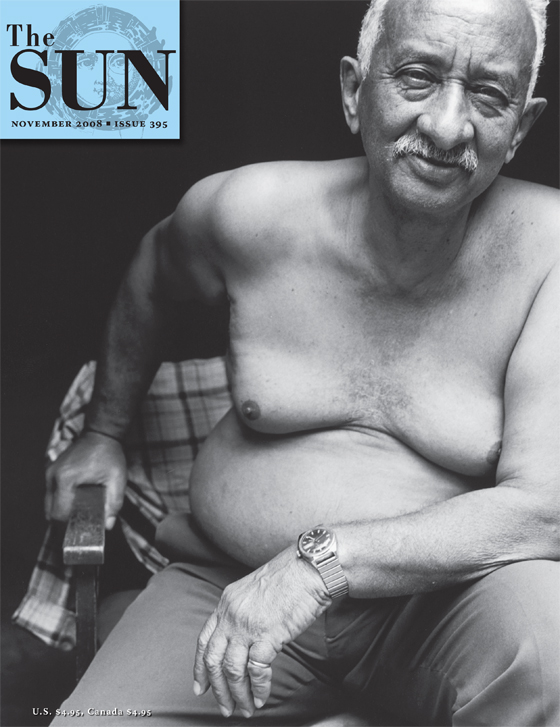

Testosterone had Daniel entering puberty at thirty, a tricky thing to manage while attending law school. I got the gossip about his soaring sex drive. He tumbled down the Death Valley dunes with the Gay and Lesbian Sierrans, took a field trip to a bathhouse and soaked in a hot tub with a handsome fireman. Daniel anticipated his body’s changes like a kid waiting for kittens to be born: “God, maybe I’m imagining this, but I think there’s fuzz on my chin!” He needed bigger shoes. Three hairs sprouted on his chest. His legs grew woolly. His voice rasped, and his parents asked over the phone if he had a cold. For the time being he said yes — they would find out soon enough. His face began to appear heavy, no longer small and round like an apple. His jaw gained definition, and his shoulders broadened. Sarian had always seemed liable to slip away, but there was more of Daniel to contend with. He worked out at the ymca and, with help from T, built muscle quickly. “It’s amazing this is possible,” Daniel admitted. “Like science fiction.”

In the beginning Daniel’s hybrid body made me uneasy — his stretched-out face and bulked-up shoulders above a slim torso. Yet his joy was obvious. He had an enthusiastic, relaxed way of being in his body. When we went out for Thai food, he put his arm around me, squeezed my shoulder, and asked the waitress to take our picture. He told me he had always lived at a distance from his body and from other people. Now the distance had disappeared.

Some trans men embrace masculine stereotypes, but Daniel was no born-again macho man: no cowboy hats, no swagger, not even an average-Joe lawyerly respectability. The gay community gave him access to camp culture, and his wardrobe embraced lime and pink. He still flapped both hands in greeting. Once, a few months after he’d started testosterone therapy, Daniel tried to open the car door for me. “Discovering chivalry?” I asked. He made an inarticulate noise, threw up his hands, and hustled to the driver’s side. He never opened the door for me again.

Even before the hormones took full effect, I began to feel that Daniel was truly male. My pronoun errors and Freudian slips dwindled. After a time, if a friend referred to Daniel as “she,” it was jarring to me, like a grammatical error: “The apple are crisp.” But I would never share Daniel’s feelings about body modification. While he made his body a playground of tattoos and piercings, I was of the “My body is an inviolable temple” school. It was hard for me not to see his scheduled chest surgery as chopping off perfectly good breasts. Breasts were innocent, soft, natural. But they didn’t make sense to Daniel. He had been wearing flattening bras for years. He shuddered and said the breasts weren’t his.

After his surgery, I put off visiting him as he convalesced at a friend’s in the far reaches of Oakland. He didn’t answer the phone, and I wasn’t sure I could muster the appropriate enthusiasm at his bedside. Then, a few weeks later, I ran into him and his new flat chest at a street fair. He asked if I wanted to see, and before I could reply he lifted his shirt to reveal two brown sickle-shaped scars where his breasts had been.

Daniel was the first, but not the only, Lesbian Avenger to transition. Within a few years of our chapter’s demise, four former members — including my co-organizer, Sam — started using male pronouns and taking testosterone. Dyke events in the Bay Area began to include “women and their female-to-male friends,” or “past, present, and future women.” The San Francisco Chronicle magazine ran a cover story about lesbians becoming men. One dyke punk star who had done her best to live up to the man-hating stereotype lamented, “I can’t complain about testosterone poisoning anymore.”

As Daniel grew larger, he donated a skater shirt, a green-striped men’s sweater, and a women’s Speedo to my wardrobe. I got a cozy feeling when I wore the sweater, as if I had inherited it from a big brother. The black one-piece suit, though, made me wistful. I thought of the body that had once worn it — the body that was now gone. I went to Osento, the San Francisco women’s bathhouse, and sank into the blue-tiled hot tub. I smiled at the other human beings there with hips, tummies, plump chests, and fur or smooth skin between their legs. There was a feeling of comfort and camaraderie when a woman poured oil on the rocks and the scent of eucalyptus filled the sauna. But Daniel could no longer come here. And any of these curvy, sweating sisters could conceivably end up male.

Though I did not want to change my body, it had always surprised me to think of myself as a woman. In junior high I had regarded the other adolescent girls as a sophisticated, alien species. When I glanced down in the shower now, my female parts still seemed vaguely improbable: Here is a vulva — how interesting. Here’s a breast — very breastlike. If Daniel wasn’t female, then perhaps my own parts did not dictate my gender either. A breast might be simply a flap of skin and fat, an appendage without the connotations of Playboy Bunny or earth mother. Second-wave feminists had reimagined the female body for decades, but Daniel’s transition brought their message home to me: my body belonged to me before it belonged to any label.

If I didn’t feel quite like a woman, and I definitely didn’t feel like a man, then what was I? Daniel defined gender as “a way of interacting with and presenting oneself to the world.” He didn’t use terms like “becoming a man” or “sex change.” As he passed for male on the surface, he felt more and more “gender queer.” He told me about a trans-male friend who defined his gender as “glitter boy.” It dawned on me that I could describe my gender however I pleased. At once I knew what I was: I was Puck.

In a high-school production of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, I had escaped into the role of Puck, servant to the fairy king, and had run about in a blue silk cloak and a crown of twigs, teasing fairies and plotting pranks. Even back then I had reflected that Puck seemed neither male nor female. When I’d put a drop of love potion into a sleeping man’s eye or darted out of a trapdoor, I’d felt like an electric, indeterminate being.

Puck treated gender identity as a charade, and so did postmodern theorists. At the end of the twentieth century, Judith Butler had proclaimed, “Gender is drag”: our layers of disguise concealed no core male or female self. Puck delighted in shape-shifting into a crab apple or a stool or “neighing in likeness of a filly foal.” He turned Bottom, the bad actor, into a donkey. When lovers quarreled, Puck mimicked their voices and led them astray in the woods. Puck might have perched in the tree above Daniel and me that day in Dolores Park, giggling at my besotted hopes and Daniel’s revelation. Puck would certainly have turned those four Lesbian Avengers into men if they hadn’t transformed of their own volition.

I began to feel that I was intrinsically Puck-like. After years of having pushed myself to be an adequate straight girl and then an earnest lesbian, it was a relief to rediscover my taste for mischief, fun, and perversity. My big eyes, large nose, and small stature fit the elfin image. (Once, a stranger in a drugstore called out, “Hey, nice smile — you look like an elf!”) One Saturday night I put on a Halloween cape and set out for a club called “Gender Pirates,” hosted by Sam, who now emphasized his budding beard with mascara. Along the way I spread my shimmering cloak and swooped and pranced past restaurant windows.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, a forefather of Romanticism, proclaimed, on the first page of his Confessions, “I am made unlike any one I have ever met; I will even venture to say that I am like no one in the whole world.” Now, in fulfillment of our own American romance with self-definition, female-to-males had become literally self-made men. Some had taken it further and declared themselves beings of their own description. Sam founded a group called “United Genders of the Universe.” Postmodern Romantics, we understood gender as both a performance and a truth.

Two years after Daniel had transitioned, I went to a party to celebrate his law-school graduation. On a cloudy afternoon in someone’s backyard in the Mission, a crowd of femme dykes, trans guys, butch lesbians, gay men, straight feminists, and Daniel’s hipster sister and brother-in-law came and went. I entertained someone’s two-year-old with a squeaky toy. Daniel bopped around, enthusing and eating barbecued veggies. When people asked how I knew Daniel, I said, “I met him in the Lesbian Avengers.” A woman with long gray hair looked confused and remarked, “Oh, really?” A blond fellow with California good looks and a triple-D chest just laughed. Daniel sat on the blond guy’s lap and engaged him in a tickle war. Susanna, the trans woman from the Avengers, showed up in a leopard-print dress and green eye shadow. Daniel’s sister camped it up in a studded belt and purple boots.

I felt a kind of satisfaction at the sight of this pageant, as one might on Noah’s ark. The myriad forms seemed to point to some irrepressible complexity of the species. If nothing else, humans could count on our capacity to surprise ourselves and each other.

But there was sadness in me as well. In the Avengers I had felt part of a tribe, and I missed my cosmically sanctioned sisterhood. I missed the music of Adrienne Rich’s “The Dream of a Common Language”:

. . . a woman’s voice singing old songs with new words, with a quiet bass, a flute plucked and fingered by women outside the law.

Instead of femaleness, what I now shared with my fellows was deviance. Any imagined kinship between us would be chosen, not ordained, and it would have to grow out of the moment-to-moment quality of our interactions — out of whatever empathy and respect we could muster.

As the afternoon got chilly, I prepared to leave. I tapped Daniel on the shoulder to say goodbye. He hugged me, and I felt his broad, flat chest with satisfaction. Then I walked home alone.