I have to begin with us in bed, Jack’s hands cupping my face, his blue eyes pinning me fiercely to the pillow, daring me to look away. I moan and thrash my head from side to side. He holds me while I cry, letting me sob freely into his chest until the storm passes through me, and I feel the shudders move from my body into his.

I have to tell you how old we are as we move apart in the practiced way of experienced lovers, his hand holding the condom close to his body, me turning, snuggling my backside to fit the curve of his belly. He is sixty and I am forty-one, dangerous ages both. Plenty of water under the bridge. Jack is five years younger than my father, but I don’t want to think about that. I have seen how age and illness and bad luck can take apart a body, and, at heart, I am terrified.

Jack spits out one of my hairs, winks at me, grins.

“You’re so proud of yourself,” I tease him.

“I just like to make you scream, you little squirt.” He tousles my hair and strides to the bathroom, where I can hear him urinating proudly. And why not? He is proud of his big body and all its functions, with the pride of a little boy still alive inside that strong, aging flesh — alive, and scared, too.

We both understand that this pleasure could go in a minute: a stroke, a heart attack, a slip, a fall. “You, too,” he reminds me, his fingers kneading my breast. In just such a way, one ordinary day a year ago, a friend — a radiant woman in her early thirties — found a lump in her own breast. That woman is now dead. A slip, a fall.

I also have to tell you that it is impossible for Jack and me to have children together. He had a vasectomy years ago, when his children were young and I was barely old enough to be their baby sitter. We have had the conversation about what happens if we get married and he dies in ten years and I’m a widow of fifty with no children, and he has said, “I refuse to distract you from your path. If it’s family, then it must be family, but I am not that man.”

And so we have agreed to have no obligation to each other, no commitment beyond . . . this, whatever it is. We are two people who understand in our bones the importance of tribe, yet our lives are too complicated for us to stay bound to the families we are still a part of. At the heart of this fullness we feel together is a sadness, and we have agreed to look each other in the eye when it comes upon us.

On Christmas Eve, Jack and I drive to my old neighborhood. There’s no light in Grace’s kitchen window. We knock on the door of her housing-project apartment. No one answers, and Jack says, “Maybe they’re not there,” but I know they are. Grace is almost always at home. And I can see her old car in the driveway, looking sheepish, as though it has recently broken down in the Safeway parking lot, or on Martin Luther King Jr. Way.

Sure enough, after a few minutes, I hear a noise behind the door and then: “Who’s that? Who’s there?”

“It’s me!” I yell. “Ali!”

“Oh, Ali. Norah, get the door.” Grace’s voice is warm and Southern, always with a faint note of wide-eyed surprise — a good concealer for anything that might automatically need to be concealed from white folks.

I lived around the corner from Grace for three years. This neighborhood is where I came to lick my wounds and Learn to Live Alone after my divorce. I was scared at first. Drug dealers occasionally got into loud midnight arguments on the street that sounded, to my woman-living-alone ears, as if they were taking place in my living room. But I stayed here because it was cheap and close to the freeway I drove to work. And because there were rosebushes in my neighbors’ yards. And because, unlike in other (whiter, more middle-class) neighborhoods, people talked to you as you walked down the street. The men said, “How ya doin’?” and, “You married?” The old women nodded and said, “God bless you, baby.”

I came here to wallow in loneliness and independence, to eat frozen vegetables from the package. (“Did you at least thaw them first?” a friend asked.) I did not expect to fall in love, but I hoped for it. I prayed for a suitable Prince Charming to ride up on a white horse, or in a battered Toyota, and rescue me from the silence that pressed in, from the days I woke up missing my ex-husband so badly I could hardly breathe.

Instead, leaning on my bell the very first day, and every day after that, were Norah and Elijah, Grace’s foster children.

“Ali, watch me do a back flip!”

“Ali, buy us a soda at the store, but don’t tell Mama, because she says don’t be begging you for stuff.”

“Ali, can you take us swimming?”

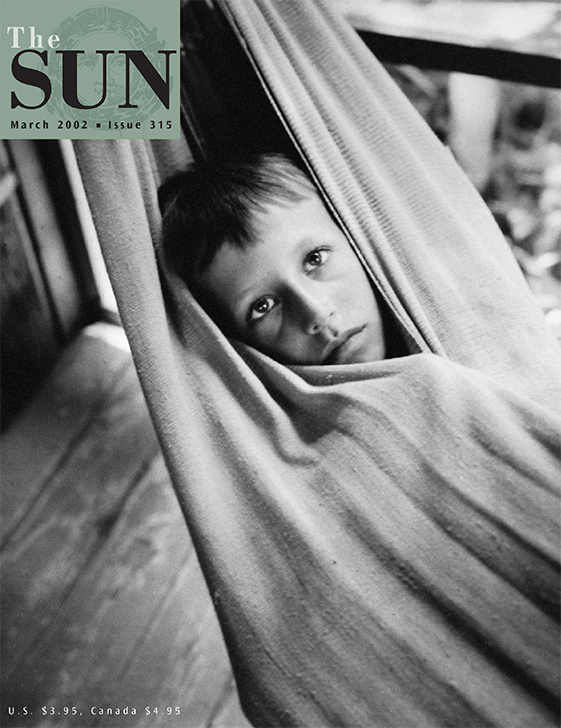

While they visited, that invisible beast Loneliness would shift on his paws and pad quietly out of the room, only to return faithfully when darkness fell and I crawled into a bed that was too big. Lucky for me, the kids always stayed as long as possible. Norah, especially, hated to leave. She’d cling to my hand or my neck with the ferocity of the early-abandoned.

Grace had taken in Norah and Elijah at a time when her own brood didn’t have enough beds to sleep in, and somehow, through a combination of welfare, food stamps, and mother wit (mostly the latter), she’d managed to keep them clothed and fed and schooled and sweet and funny. I was an extra adult with a running car, a few spare dollars in my pocket, and a hunger for family, and so I became their raggle-taggle white auntie. It is on the basis of this makeshift relation that I have come around now on Christmas Eve with my nervous not-quite-boyfriend on my arm.

Norah greets me by throwing her arms around my waist and squeezing tight. We rock back and forth a minute while Jack takes in the surroundings. The kitchen counter is stacked with dirty plates and pots and pans — evidence of five or more teenagers coming and going and cooking and burning and eating. The kitchen table is covered with clutter: homework papers, a bowl of plastic fruit, some real fruit going bad, cereal bowls crusted with milk and soggy Cheerios, a rabbit cage, newspapers.

In the living room, Grace sits regally on her plastic-covered red armchair and smiles at us from underneath a waterfall of shiny curls: a new wig. She does not rise; her arthritis must be acting up. The coffee table is buried under opened Christmas presents. In the corner leans a small tree, weighed down with ceramic angels. Fat candles, striped red and white like candy canes, are stuck into star-shaped holders. Piles of folded and unfolded laundry slump against each other on the plastic-covered couch. The loud, oversized TV dominates the room. On the screen is the new, updated Leave It to Beaver. The original was the suburban ideal of my childhood, the one we were brought up to believe in: white picket fence; smiling parents; small, comic problems, easily fixed.

Norah stands next to the parakeet cage, touching it with a finger. It’s always awkward, the shock of seeing each other again after a few weeks. I feel like a guilty divorced father who’s been skipping custody visits.

“Norah,” Grace says, “get Ali some tea. And for her friend, too.” She asks Jack and me, “Do you want some tea? I got that kind with no caffeine.”

We nod. I push aside some laundry and sit on the couch. Jack folds his long body into a chair in the corner.

“I just brought over some presents for the kids,” I say.

Grace is watching the TV with one eye and talking on the phone to her ninety-year-old father back in Louisiana. “But, Daddy, I think you ought to get them tests done,” she says into the receiver. “What do Wilfred say? Mmm-hmm.” She interrupts her conversation. “Norah, get Ali and her friend some fudge . . . on a plate!”

On TV, Wally and the Beaver have been invited to a party where the kids are going to play (snigger, snigger) spin the bottle! Beaver is in agony, anticipating his first kiss. Apparently, the show hasn’t gotten any more enlightened in the thirty years since I last watched it.

Grace smiles at the program. “Lord, I remember my first kiss,” she says after she hangs up with her father. “A boy stole it from me. Yes, he did! And I was so upset because I was only twelve, and I thought if a boy kissed you, you’d come up pregnant! I cried for three days. We was so innocent in them times.”

“Ignorant,” Jack says feelingly from his crowded little corner. He has told me about how it felt to be a teenager in the fifties, when the fear of pregnancy loomed dark in the waters of adolescent petting like the Loch Ness Monster.

“Ignorant,” Grace agrees, shaking her curly head. “Land, we was ignorant. Even though I used to share a bed with my cousin who had a baby every year. When I was little, it scared me, the sounds she made when the baby come! I used to squinch my eyes up tight — Norah, get them some napkins — ’cause I didn’t want to see.”

Jack leans back into his chair, a rapt look on his face. He loves a good story.

“In those days,” Grace says, “the old folks, they really punished you if you was pregnant and not married. I remember my cousin sitting on the back porch ’cause her belly was big and she wasn’t allowed to sit on the front porch no more. After the baby come, all the folks would rally round and help you take care of it, but when it was just you with your big belly and no ring on your finger, they would talk about you, but they wouldn’t talk to you. That’s just how it was.”

“That’s how it was,” Jack agrees.

In a former life, Jack traveled all over the South with his ears open and his big cameras ready, documenting the civil-rights movement. He photographed many poor black families and wrote down their stories. The work taught him how to shut up and stay out of the way, he says. Now he half closes his eyes and nods encouragingly as Grace sails into the memory like a ship with a full wind behind her:

“My cousin’s mama always used to deliver them babies. One time, the baby was turned around wrong. It couldn’t come out. My cousin was crying and saying, ‘I can’t, Mama, I can’t.’ And her mama just up and smacked her hard on the behind — pow! Then she felt the baby turning hisself around, and she said, ‘Oh!’ It come out just fine.”

Grace smiles. I imagine her as a round-faced little girl, the screams and smells of birth all around her. She and I talk about men sometimes, when I come to pick up Norah and Elijah for an outing. I’ve introduced her to one or two of the men who have taken a spin on the merry-go-round with me before deciding they couldn’t afford to go for the brass ring. She never judges, just tells me, “I been celibate for the longest!” and laughs, shaking her head. “Done had me enough problems already.”

It was after her husband left for good — “Drugs,” she said succinctly — that she took in Norah and Elijah as foster children. Then, when her brother died, his widow and her five children came to stay with Grace. How they all fit into this apartment I’ll never know. They stayed until a neighbor reported them to the Housing Authority. Even now, when I come over, there’s often somebody sleeping on the living-room couch, nestled in among the piles of laundry, and someone else curled up on a sleeping bag on the floor. There’s always room at the inn.

Grace is lost in her memories. “Two or three she had sitting on the slop bucket, you know. It kept the sheets from getting messed up.”

Behind his half-closed eyelids, I imagine Jack is seeing the exact scene she is describing, as he saw it in Alabama and Mississippi thirty years ago. I try to picture him the way he was then, big and young and raw, frightened but also intrigued to be so far out of his element, moving his equipment carefully so as not to interfere with the tableaux he was trying to capture.

“And for when the afterbirth come out, too,” Grace says. “You want some more tea?” She glances up at the TV. Beaver is standing in a closet with a cute but hapless little girl. They decide not to kiss but to tell the others that they did. Beaver emerges swaggering, hitching up his pants like John Wayne. Grace smiles. “I always did love the old Leave It to Beaver. That was our favorite show back in them days.”

At George Washington Carver High School, where I work, Damon and I lead lunchtime drop-in groups where students can come and talk about drugs and alcohol. Damon’s a big man who drives a motorcycle and has tattoos on both arms. He did his own time with drugs, and the students respect him for it. I try hard not to be jealous of this.

We usually get most of the football team, plus a couple of girls. That’s how it is today. The air thickens with testosterone as the guys start bouncing insults around the circle like pinballs.

“Yo, how come Joe got two pieces of pizza?”

“I ain’t got two, nigga. You lie like a rug. You lie so much yo’ mama like to vacuum you.”

“At least my mama be home with the vacuum, not out on the street like a —”

“Hey, that’s enough,” I interrupt. I hand out pizza slices while Damon introduces today’s discussion topic.

“Say there was this box,” he begins. “Let’s call it the happiness box.” He draws a coffin-like shape on the blackboard. “And if you get inside this box, they’ll hook you up with electrodes, and you’ll be happy; not bored, not lonely, not wanting for anything. Happy and fulfilled for the rest of your life. Of course, your muscles will turn to mush, but, hey, so what? You’re all hooked up. You’re happy. And you can leave anytime. But here’s the catch: no one ever has. Once they get in the box, they want to stay there. So, would you do it? Would you take a crack at the happiness box?”

“Hell, yeah!” Big Joe shouts from the corner, where, yes, he did manage to sneak two pieces of pizza.

“Hey, what this pizza got on it?” Malcolm asks with disgust. “Corn?”

“It’s gourmet pizza, Malcolm,” I explain. “We get it donated. People in Berkeley are lining up to buy this for two dollars a slice.”

“Yeah, but why they got to put corn on a pizza, man? What about something that belong on a pizza, like meat?”

“See, if you were in the happiness box,” Damon smoothly redirects, “corn on the pizza wouldn’t bother you. They could feed you mashed turnips, and you’d be perfectly happy all the time.”

“Like one of them Buddha people?” Big Joe asks. “Just be sitting around like —” He imitates a blissed-out meditator with a beatific smile on his face.

“Hey, do you get to have sex in the happy box?” Malcolm asks.

I have been wondering the same thing myself.

“You don’t want to have sex,” Damon says.

Malcolm frowns in disbelief.

“You’re happy without sex,” Damon insists. “The happiness box gives you that same feeling of relaxation and bliss but without all the trouble of finding a girl and scoring —” I shoot him a look, and he catches himself. “Without all the responsibilities and hassles that go along with sex. Without the danger of disease or pregnancy.”

Cleopatra speaks up. “I don’t want to go in the happy box,” she declares.

“Why not?” Damon challenges her. “Don’t you want to be happy?”

“Sure I do, but I think that working through my problems is what makes me grow and learn.”

I’m impressed. I have counseled this girl one-on-one, and I know her family life has been poisoned by drugs: her grandfather and her auntie run the whole West Oakland crack operation, her mother has pulled a gun on her, and her brother was shot in a drug deal.

Sometimes, when I hear about the violence in these kids’ families, I wonder why anyone would think having children automatically brings happiness. It’s so hard, almost impossible: kids and grown-ups cooped up together in too-small apartments, unable to communicate, the spoiled milk of anger stinking under the fridge, the alarm clocks and sirens and stress of it all.

But Cleopatra’s answer touches me. I jump on it: “Tell us more about that, Cleo.”

“I just think, you know, it’s like working out: you have problems in life to give you stronger muscles.”

Now she’s hit on a metaphor that the football team can relate to.

“I change my mind,” Joe says. “Take me out of that happy box.”

“Why?” Damon inquires. “You want to suffer?”

“No, but I don’t want my muscles to look like no waterbed, neither. Shit!”

“So,” Damon asks incredulously, “no one wants to go into the happiness box?”

“I do,” Otis pipes up. His dark, skinny biceps are beautiful under his loose football jersey. “I got serious problems.”

“But think about your body, blood,” Big Joe interjects. “Your muscles gon’ be like mash potatoes!”

“I don’t care,” Otis insists. “I just want to be happy. I really do. I got too many problems. Put me in the box.”

“But is that really going to make you happy?” asks Keisha, the other girl in the room.

“I tell you what make me happy!” a boy in the back says, pumping his forearm up and down suggestively. The other guys hoot.

“OK, sex makes you happy,” I say. “What else?”

The boys shout out answers:

“Video games!”

“When I win the big game and all the fans be cheering me on and they hand us the trophy.”

Damon scribbles the replies on the board as fast as he can. He catches my eye and grins. “It’s true: we are the simpler gender,” he says.

“OK,” I say, “video games, sports . . .”

“Family,” Keisha calls out. “When the family all together and loving each other, that’s a happy time for me.”

“Weed!” shouts Malcolm. “That’s my happy box right there.”

“OK, weed,” says Damon. We have arrived at the crux. “What about weed? You know anyone who likes to curl up inside a joint or a bottle and never come out?”

“My uncle!” Otis says. “He in his happy box almost every night. ’Course, I’m in mine, too.”

“Right, we’ve all got our happiness boxes,” Damon agrees. “The question is, do we have the power to leave them and come out into the world and deal with our problems?”

“I can quit anytime I want to,” Joe insists.

“Yeah, you quit five times last week alone,” Malcolm says.

The bell rings. Group is over.

“What about you guys?” a boy named Sasha asks shyly as the rest of the students file out, bumping and shoving and grabbing at the remains of the pizza. It’s the first time he has spoken.

“Motorcycles are kind of a happiness box for me,” says Damon. “And, as you know, I did my time in there with drugs. But I found that, when I came out, I had even more problems than before. Now I don’t want to be in a box if my loved ones are out in the world struggling. My place is with them, helping out if I can. But I understand the desire.” He turns to me. “What about you?”

“Never,” I say quickly — too quickly. “I’m an artist. It’s my job to experience all of life — the good, the bad, and the ugly — and then to tell about it.”

“And, besides,” Damon points out helpfully, “you like to suffer.”

“So, how come you haven’t called?” I ask Jack while balancing the phone receiver, a bad cough, and a cup of ginger tea with honey. Outside, the rain falls steadily.

“What do you mean?” Jack says. “I’m calling now, aren’t I?”

(Bad move, Ali. Now he sounds defensive.) “You know what I mean. I’ve been sick for two weeks —”

“How are you feeling?” he jumps in solicitously.

“Shitty. Plus I have a hunch something’s up with you.”

“OK,” he confesses. “It’s this girl. The one I told you about.”

“You mean what’s-her-name? The twenty-eight-year-old?”

“Gwendolyn. She’s almost twenty-nine.”

“Jack.”

“What? We had an agreement.”

Ah, yes, the famous agreement, the one he makes with all his lovers. (Be cool, Ali. . . . ) No, why the hell should I be cool? “You’re going out with someone named Gwendolyn who’s almost twenty-nine, and you don’t call me for two weeks while I have the flu: what’s wrong with this fucking picture?”

“See, I knew you would be upset.” He sighs.

“I’m not upset — I’m homicidal. I just can’t figure out which one of you to shoot first.”

“Look, I know she’s too young for me. I know it won’t last; she’s leaving town in six months. But, for right now, she makes me happy, and I need to feel that way. I’ve had a hard year.”

There’s not much I can argue with there. It’s been hard years all around, for me and everyone else I know. We help to make it that way, with our desires and fears. I could be mad at Jack right now, but I’m just as ambivalent as he is, and we both know it, so my self-righteousness sounds a little feeble.

Jack goes on explaining: “She lives in my town, not an hour and a half away in a goddamn ghetto —”

“I do not live in a ghetto!”

“All right, barrio, then. And she’s comfortable and easy. We just enjoy our time together. You . . . you want things. I can see it in your face, even when you don’t say it. And I can’t give you those things. Do you hear me, Ali? I can’t. And it hurts me not to be able to. Look, I’m sorry.”

“Oh, great. You’re sorry.”

“I really am. But I’m also doing you a favor. No one wants you to be happy more than I do. I mean that. If I could find the guy who would do it, I would pay his plane fare from Alaska. Because you deserve it, Ali. We all do.”

“You’re the last person I ever expected to spout New Age bullshit at me.”

“The point is, you have to figure out where your happiness lies and go for it. You want a family? Go for a family. Maybe you won’t get it, but I don’t want you blaming me ten years from now when you’re miserable and you don’t have your dream.”

Damon opens packages of fluffy white bread, ham, and American cheese from Safeway. We’re fixing sandwiches for today’s group. “I’m worried about Cleo,” he says as he sets out twenty slices of bread, assembly-line style, then starts slathering them with bright yellow mustard.

“Why?” I ask. “Because she hasn’t been to group lately?” I follow behind him, laying one pale red slice of supermarket tomato and a watery leaf of iceberg lettuce on each sandwich.

“She hasn’t even been to school lately.”

“What’s the story?”

“I don’t know. I saw her hanging out by the steps with her buddies as I drove up. She was smoking.”

“I’ll go out there.”

At lunch, the boys play basketball and the girls hang out in little groups, their faces carefully made up. This year the style is light blue frosted eye shadow above thick black eyeliner, framed by a cascade of shellacked ringlets. It looks good on a fresh, young, sixteen-year-old face. Of course, everything does.

Most of the girls wear painted-on jeans and tube tops, but some of them — Cleopatra is one — wear baggy jeans and loose T-shirts. I remember that game of concealing and showing off. I remember feeling one day like the queen of sexy and the next like the fattest creature ever to walk the earth.

I find Cleo by the steps, just as Damon said, cigarette in hand. She sheepishly grinds it out when she sees me. “I was just holding it for a friend,” she says, not expecting me even to pretend to believe it. Damon’s right: she doesn’t look good. There are dark circles under her eyes. I invite her to my office to talk.

“I’ll come by in five minutes,” she says.

I know she can’t risk the embarrassment of trailing after me through the crowded lunchtime schoolyard. I also know that “five minutes” might mean never. I hate to let her go, but I have to act casual. So I slip back to my airless little closet of an office and wait.

Fifteen minutes later, to my surprise, Cleo comes strolling in. “Got any pizza?” she asks, sinking into the swivel chair and rolling back and forth just for the fun of it.

“Nah, we’ve got sandwiches. You hungry?”

“Not really,” she says, avoiding my eyes. “How much money you make at this job?”

I laugh. “Not enough.”

“You got to go to college to do this?”

“Well, it helps. But experience is better. Why? You think you might want to be a counselor sometime?”

“Yeah, I’d like to talk to kids.”

“You’d be good at it.”

Silence. She looks away. Communicating with an adolescent is like crossing a river on a slippery log: any false step can land your ass in the water and make you look like a fool. But you can feel the kid silently calling out to you from the other side of the river, begging you not to give up.

“I hear you haven’t been coming to school lately. How long has it been?”

“I dunno.”

“Anything going on at home?”

“Yeah, my mama kicked me out again.”

“Any idea why?”

“I dunno. She has too many stupid rules.”

Best leave that one alone for the moment. “So, where are you sleeping?”

“At my auntie’s. But she say I can’t stay long, because she don’t have the room, and she be scared I’ll get my cousin in trouble.”

“Are you worried about where to go next?”

“Yeah.”

“Would it be OK . . . I mean, would you mind if I talked to your mom? Maybe we can straighten things out, if it was a misunderstanding or something.”

“Wasn’t no misunderstanding. She want me out of there. She said so.”

I look at her beautiful, closed-off face, still round with baby fat, and think, Cleo, Cleo, Cleo. I know for a fact that I’m inadequate to this situation. But I also know that, for better or worse, I’m the only one here.

“So, do you want me to call your mom? Can I do that for you?”

She shrugs. “If you want to.”

“I do.” It’s a lie. I don’t really want to call this strange woman and be a nosy counselor butting into her private relationship with her rebellious teenage daughter. But the raw, exhausted look in Cleo’s eyes says, Do something, even if I don’t know exactly what the best thing would be.

Cleo’s mother returns my call while on her break at the bank. Her voice is heavy with fatigue. “She in trouble again? I ain’t seen her for three weeks.”

“She’s not in trouble with the law, if that’s what you mean. But she’s been skipping a lot of school, and we’re concerned. She was doing so well this semester, but then everything seemed to go downhill about a month ago.”

“Yeah, well, I told her to stay in school, but I can’t make her. She’ll tell me she’s going to school, and then she’ll slip out and hang with her friends, getting into all kinds of trouble. I’m so tired of her lies.”

“She said you told her she couldn’t stay at home anymore.”

“Yeah, I did. I’ve got a ten-year-old, and I don’t want her getting any wrong ideas. I don’t know what she told you, but that girl will manipulate and lie until you don’t even know up from down. You got any kids?”

“No.”

“Best keep it that way. You don’t even know what heartache is until you got a teenager.”

Tilden Park, in the hills above Berkeley, is warm and brown in late January. Prickly bits of thistle cling to our shoelaces as Norah, Elijah, and I edge across a leaf-littered log bridge.

“Let’s pretend we’re Indians,” I tell the kids. “See how quietly you can step.” Of course, the Ohlone and the Miwok didn’t wear oversized Nikes with bright lights flashing on their pumped-up soles. Still, it feels good to invoke them.

We have already made our ritual visit to the petting zoo, where we fed limp shreds of lettuce to the pushy donkeys and patted the goat, with her smooth head and slotted black eyes and swollen milk bag hanging low between her legs like a water balloon about to burst. Now Elijah, who had to be unglued from his PlayStation before he could leave the house, has come alive again in the silence of the woods.

Norah sees the lizard first. (Or is it a newt?) He moves when prodded, turns over, and begins to crawl, lumbering slowly over her small pink palm. She squeals as his feet tickle her wrist.

Elijah snatches the lizard from Norah. At first, he was just entranced by it. Now he’s seriously in love. “Please, Ali, please, can we take him home? He has green eyes. He’s looking at me! Look at his orange belly. Aw, he’s so cute. I promise I’ll take good care of him. I promise, I promise, I promise. Please, Ali, please please please.”

Norah, who’s used to Elijah taking things from her, is hugging the tall, scarred eucalyptus. She cranes her head back, studying the ragged bark hanging off the trunk in fragrant strips. A few feet above her head, lovers’ initials are carved into the tree’s flesh. “Why they do that?” she asks.

“Because they loved each other and wanted to make a mark to last forever.”

“ ’Member when we used to come here when we was little?” she asks, breaking my heart. I used to bring them here every week — here, or to the beach, or to the flea market, where Grace and I would pick through piles of old clothes while the kids tugged at our sleeves and begged for plastic guns and cheap mermaid necklaces. Now that I live across town, I sometimes let a month or more go by without making the time to visit. How strange and painful is this role of being not-quite-auntie, not quite there, not quite anywhere.

“Hey, Ali,” Norah interrupts my reverie, “what happened to that Bill Clinton guy?”

“Bill Clinton?”

“Yeah, that guy you brought over on Christmas to see us,” Elijah chimes in. “With the gray hair.”

Bill Clinton, huh? Jack will get a kick out of this when he hears about it — sorry excuse for an ex-boyfriend that he is. “Oh, I don’t know, honey. I’m not seeing him much lately.”

Elijah is concerned. “You had a fight, huh? What happened? You all was talkin,’ right?”

“No, we didn’t fight. It’s just . . . sometimes people want different things.”

“I know,” Norah announces loudly, putting her hands on her hips and rotating her head around the way she has seen the girls do on TV. “You don’t have to explain it to me: mens!”

I laugh, and we continue trooping through the woods, Elijah bearing the lizard reverently on his open palm like a devotee carrying an offering. “Please, Ali, please please please!” he repeats, on the not unreasonable theory that I will say yes just to get him to shut up. It has worked before. “I’ll take good care of him, I promise!”

I have seen the signs warning people not to remove any creatures from the park. I understand the importance of protecting wild animals, of keeping what wilderness we have left as natural as possible. I have a pretty good idea what the odds are of this lizard’s survival in an enthusiastic ten-year-old’s grasp. But I’m faltering. I try a weak argument: “How would you like it if an alien came down and grabbed you and took you up to his planet?”

Elijah is way ahead of me: “I would like it! I’d want to see what his planet looked like!”

I weigh the life of a small brown lizard with green eyes, a rust-colored belly, and sweet suckers on its feet against the ardent desire on Elijah’s face. These are the last days of his childhood. How many more times will I have a chance to kindle so great a joy with so small a thing? How long will it be before Elijah becomes like Malcolm, jaded by the cheap happiness of a ten-dollar sack of weed? How long before Norah’s eyes are as empty and tired as Cleo’s?

“OK,” I agree weakly.

Elijah’s face lights up like a firecracker. “Yippee!” He hands the poor lizard to Norah and does one, two, three cartwheels in a row. “Ali, I bet you don’t know how many muscles in the human body. Two hundred and six!” And then he is off, unable to contain himself a moment longer, zigzagging and whooping through the hushed woods.

Later, after I’ve bought them ice cream, dropped them off at their house, and driven across town to my own peaceful den, the phone rings. It’s Grace:

“Ali, what is this thing Elijah’s got? I put him in water, but he like to drown. Called three pet stores, and they couldn’t tell me nothing. Finally, I called this place that’s just for lizards. They say he’s a newt. And he don’t eat lettuce; he eat insects. I ain’t got no insects this time of year.”

“I’m sorry, Grace. I knew it was the wrong thing to do, but he begged and begged.”

She laughs. “I know how Elijah is, but you got to say no to him.”

As always, I am humbled by her common sense. Grace takes the time to call three pet stores and a herpetarium because what passes between her and these children is not about happiness. It’s about love: a love so big it encompasses happiness and unhappiness; a love that doesn’t end with keeping these young ones clothed and fed, but extends outward to all the places her children wander, and to all the creatures they bring home.