The phone rings during dinner. The break in the silence is a relief, but I don’t move. In fact, I pretend I don’t even hear it. I’m fifteen and angry at my father for making me stay home again on a Friday night. He pretends not to hear the phone either. Perhaps he’s afraid it will be another of those dinnertime telemarketers asking for “the lady of the house,” and he’ll have to fumble through some awkward explanation about how she’s deceased and could they please remove her name from their list, and then he’ll hang up and pretend the conversation never happened. But after three rings, he decides to risk it. Could be work. Wouldn’t want to miss a work call. He gets up from the table.

I push my food around my plate. Lasagna again, this one a vegetarian dish from one of Dad’s co-workers. I hope the phone is work and he has to go in for a few hours. Otherwise, we’ll finish dinner, I’ll do the dishes, and then we’ll sit in the living room and watch TV until bed. We won’t talk. He’s never been much of a talker, and now neither of us knows what to say.

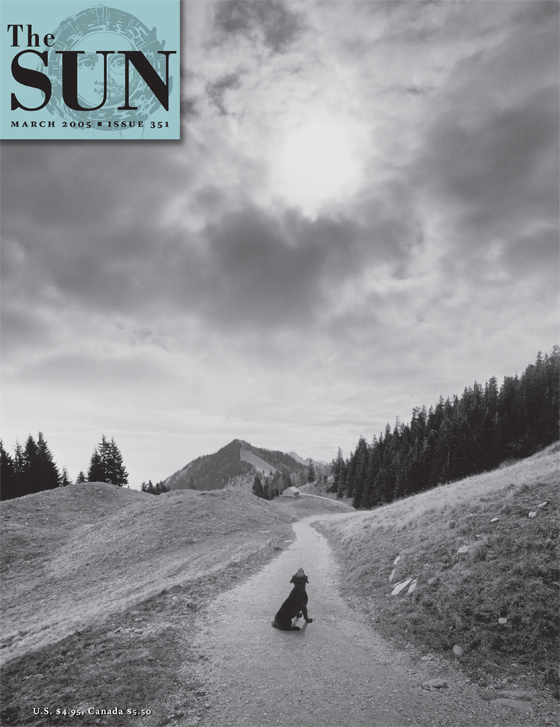

Dad comes back to the table and starts eating again. I wonder who called, but I don’t want to ask, so I keep chewing. He stares at the wall, not seeing, clearly thinking of something else, probably work. His eyes rest on the calendar Mom bought to support the Humane Society. Almost every block is filled with her writing. Though the month changed more than a week ago, neither of us has flipped the page.

And then Dad breaks our silence. Without looking at me, he says, “Junior Harrington. He just killed one of his cows. If we want some meat, we should go help him carve it.”

I’m in midbite when he says this, and I almost spit my food out. “What?”

He sets his fork down. “Junior killed one of his cows, and we should go help him if —”

“I heard you the first time,” I say in a disgusted tone I’ve perfected since the accident.

Dad goes upstairs, and I clear the dishes, then sit at the table and flip through a catalog. Dad returns a few minutes later wearing his weed-whacking pants and a flannel shirt that Mom bought him when we moved to the country two years ago. She said it would help him fit in with the neighbors. He’s never worn it before. Dad takes the keys to the Volvo off the hook by the door.

“We could use the meat,” he says, not looking at me.

“You’re going to help some guy you don’t even know carve up a cow? What do you know about cows?”

“Nothing. Let’s go.”

“You’re out of you’re mind.”

“Maybe. Get your jacket. It’s cold out.”

Perhaps out of curiosity, or perhaps out of shock at the length of our conversation, I pull my jacket off the rack and stomp out to the garage. Dad brings his work gloves, still unused. I sit in the passenger seat, arms crossed, as we drive to meet Junior at the slaughter.

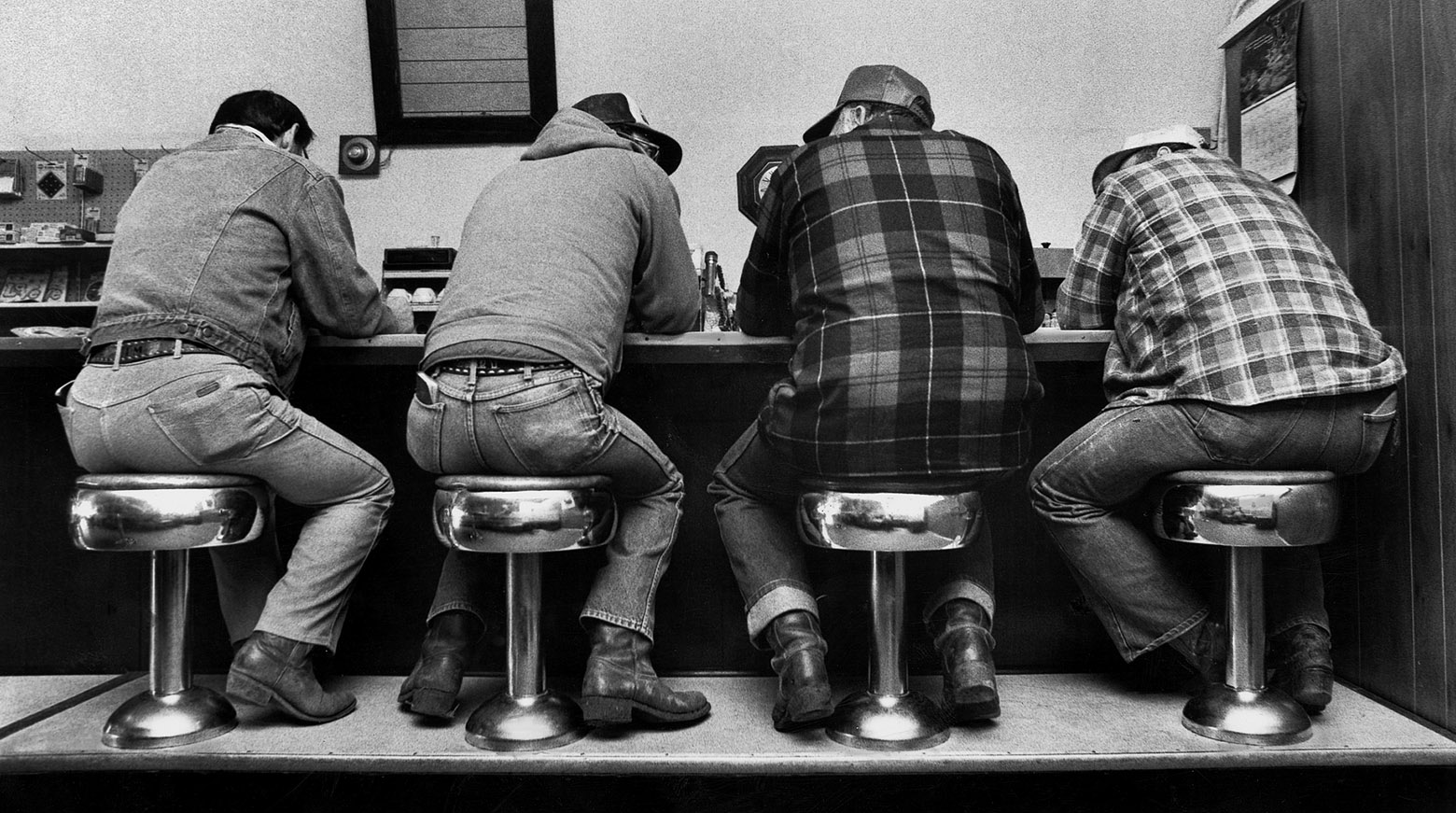

Hollis Road is little more than a dirt track that crosses Junior Harrington’s property about a mile from town. Not many people travel it, unless they happen to be a Harrington. The Harringtons own most of the farmland this side of town, and what they don’t own they did at one time. I have never been on their property before, and I feel as if I’m trespassing. Dad guides the car slowly around the curves. After three or four turns we see a half dozen men standing in the road, looking down at what I assume is a dead cow. Dad parks behind a row of pickup trucks and gets out.

“I’m not coming,” I say.

“Suit yourself.” He takes his Red Sox hat from the back seat, secures it on his head, and leaves me there alone in the car. After a moment my curiosity overtakes my stubbornness, and I follow him. With hands in my pockets and a disinterested look on my face, I lean against one of the trucks, close enough to listen, but far enough not to be inside the circle of men. The only one I recognize is Junior, a short, hairy man I’ve seen down at the general store. He sees me but turns away.

The men nod at my father, give a few low heys, though they’ve never officially met him. And then I hear my dad’s nervous voice: “I’ve, uh, never done this before.”

“ ’S’all right,” Junior says. Mom pointed him out to me at the store our first month here. She told me that if I got to know only two people in town, Junior should be one of them. “He knows everyone,” she said, and she rushed down the aisle to talk to him as I escaped to the front steps to avoid embarrassment. Now I see him hand my father a knife.

Through the men’s legs I see the cow’s body lying across the road, steam rising from her side. She’s a milk cow. I don’t know much about cows, but before we moved here I had to sit through Mom’s lectures about cows and maple sugaring and the Green Mountain Boys. I remember that the black-and-white ones are usually for milk, and the brown ones for meat. This one has been slit from her udder to her throat, and the blood forms a dark and speckled halo in the dirt around her body. A mess of intestines and organs, now matted with gravel, has spilled out. Two men use metal rakes to move her insides away from her body, and a third, with a cigarette clamped between his lips, kneels before the opening with what looks like a sponge and cleans out the stomach and chest cavity. I’ve never seen so much blood. Even though I want to go back to the car, I can’t help but watch as my father approaches the body. I move closer, crouching beside one of the trucks.

Junior and a tall, bearded man with a John Deere hat remove a section of hide from the carcass with a long knife. Though their hands are large and clumsy-looking, their movements are deliberate and almost gentle.

“Deana here wouldn’t move fast enough for Junior,” says the man in the hat, pulling back the hide with one hand and using the edge of his knife to cut it away from the muscle. “Always was stubborn.” He looks up at the other men. “Junior never has had much patience, has he, boys?”

The men smile, and a few laugh.

“Got no use for stubbornness,” Junior says.

The man in the John Deere hat chuckles. His bare hands are covered in dark blood, and he wipes them on his pants. With his knife Junior traces a faint line through the flesh of Deana’s side, then nods to my father. “Go ahead. She can’t feel nothing anymore.”

My father leans over the cow, his running sneakers already covered in blood and dirt. The men gather around him, some with bottles in their hands, others with knives. Junior removes his hat and wipes his forehead with the back of his hand. He was at the funeral. I remember that now. Stood in the back looking uncomfortable, his hat in his hands, his jeans pressed, his wife by his side. He nodded at me, and his wife smiled. I didn’t know why they had come. My father did not cry. My aunt from Boston held my hand and sobbed, and I wiped my eyes through the whole service. But my father just stood there, not even watery-eyed.

Now on his knees, my father inserts the knife at the spot where Junior’s finger points. I can’t see his face.

“Cut yourself a tenderloin,” says Junior, and then he gives slow instructions, recognizing that my father doesn’t know how to do this: “That’s it, down toward your knee. Now across to her udder, and then back up to the spine.” I move a little closer. I can see my father’s hands now. The cow’s warm muscle peels back in the wake of the tentative knife point, the layers separating. Dad pauses and scratches his shoulder, leaving blood there, and wipes his face. I can’t get any closer without joining the circle, so I stay where I am. Deana’s smell comes to me in waves, and each time it does I breathe in the wet, sweet, metallic warmth of her before the breeze carries it away.

My father’s hand has slowed, but his knife is more certain, no longer trembling but gliding surely. He has gone over the same lines three times, but the men don’t stop him. They let him keep cutting until he’s too tired to continue.

Junior nods to the man in the John Deere hat, and he brings my father a beer. Dad removes a glove and takes it, still kneeling in the bloody dirt, still staring at the cow.

“She was a good woman,” Junior says.

The men remove their hats, and for an instant there are no sounds: no cows in the distance, no clink of bottles, no chafing of jeans or spitting. My father seems small in the silence, smaller than he’s ever been. I think maybe I should go to him, but I stay where I am. Leaning over, Junior takes the knife and finishes carving the meat. The men put their hats back on their heads. Some open new bottles, and some move to help Junior cut up the carcass. They work around my father, who remains kneeling and still in the middle of the circle of men.