Back then, we carried brown paper supermarket bags filled with trash down the dark apartment-house steps to the incinerator, pulled a handle, dumped the bag onto a metal lip, and let go. Now we drive three miles to the town dump to recycle glass, plastic, and paper in clear, twist-tied bags, a yellow Town of Shelburne sticker stuck to the side of each one.

Now we sit outside at night and watch the sky: stars, satellites, planets, meteors, the reliable moon, the Milky Way. Then I’d sneak past Mrs. Ross’s apartment and up the stairs piled with her discarded New York Posts to the forbidden rooftop, where I’d creep like a spy over the tarry surface, lean against the stained brick chimney, and look up. Then I heard traffic and planes. Now I hear animals and insects — and planes still, but much higher in the sky, on their way to Manchester or Boston.

Then we crouched under desks during air-raid drills, our hands clasped behind our necks, in fear of the Russians. Now we go about our business, vaguely afraid of vague terrorists, hearing bad news on NPR, war after war perpetuated in our names, and in the name of democracy, and in the name of God.

Then we had 33s, 78s, 45s, and I sang along to the Everly Brothers, Nat King Cole, Frank Sinatra. I danced the twist with my mother to Chubby Checker until the tchotchkes in the breakfront rattled. Now I sing along to CDs. Then I listened to the Beatles sing “Here, There and Everywhere.” Now I listen to world music, show tunes, folk, jazz, soul — and the Beatles, still.

Then orange juice was made from frozen concentrate, and my mother mixed it and thrust a glass of it in front of me first thing every morning. Now orange juice comes in waxed cartons, with pulp or without pulp (or with some pulp), with or without calcium and vitamin D, low in acid, from concentrate or freshly squeezed. Then we ate salami, pastrami, tongue. Now we eat yogurt, tempeh, tofu.

Now I live in a large house with one other person on four acres of land with eight garden beds. Then I lived in five rooms with four other people and two potted plants. Then I had a parakeet; now I have a canary. Then death was terrifying and infinitely distant. Now it is known: two parents, two good friends. Then I was scared of boys. Now I’m bored by most men my age. Then I yearned for romance. Now I know its greatness and ruin, and I cherish the steadiness of steadfast love.

Then there were penny loafers, patent-leather Mary Janes, and Keds. Now I have clogs, sandals, boots, and sneakers. Then I was shy and didn’t say what I thought. Now I tell the truth as I see it, perhaps too readily. Then I wanted to write books; now I’ve written five. Then I relied on a body that was entirely cooperative and finely tuned. Now I live in one that, like my ’97 Toyota, sometimes startles me with its signs of wear and tear. Then my hair was dark brown; now it’s mostly white. Then I felt trapped. Now I feel almost too free to choose how to spend my days.

Then I had a foam-rubber pillow and slept alone in flannel pj’s. Now I have two feather pillows and sleep in a white cotton nightgown beside my gentle husband. Then my mother dictated what I ate; now I have chocolate every day and bacon whenever I want. Then she made me dust the blinds and furniture every week; now I dust about once a month. Now, to get places, I walk, drive, or fly; then I walked or took buses or subways. Then I knew the rules; now I know there aren’t any.

Then I was afraid of God. Now I pray to God daily to shelter me. Half the time I call God “her.” Then it was always “him.” Then everyone was “fine.” Now people say what’s wrong, try for the truth. Then the word cancer was rarely spoken. Now I hear it almost every week. Then I yearned to be noticed, to be seen. Now I take joy in the seeing. Look at the bark of that birch. Hear the spring water running down the hill. God! Bend over here and look at the dozens of tiny shadows cast by the setting sun.

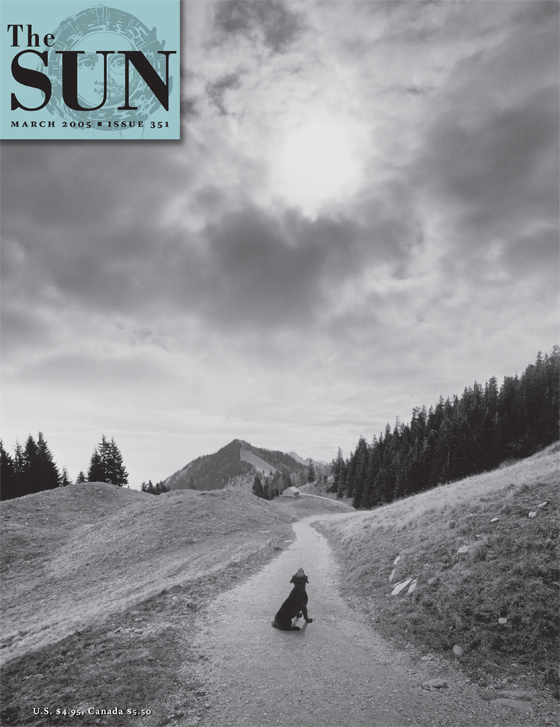

Then I was a child. Now my children are adults; I stare up at my son and marvel at the breadth of his shoulders. Then I told my mother nothing. Now my kids often tell me more than I want to know. Then life used me, propelled me, hastened me. Now I bow and walk toward something I still cannot name but see more clearly and know myself to be a part of, albeit a small, small part. Then I couldn’t bear the thought of my not being, of a world without me. Now I often yearn for union with the ineffable, beyond any idea of me.