Three months after his aging daughter Rhonda gave him a one-year-old poodle-Lab-golden-retriever mix to keep as a pet, Felder came to believe that the dog — who looked at him mournfully whenever he went to the bathroom and waited for him by the door, as still as a statue, until he came out — was in fact none other than the reincarnation of his sister, Esther, may her name be a blessing. Esther, who was seven years his elder and his de facto mother, had been taken to Bergen-Belsen during the war and had never been heard from since. Even those survivors who had been at the camp at the same time as Esther had no recollection of her: not even her name rang a bell. Esther — there were lots of Esthers. Lots of Esthers. Lots of Ettas. Lots of Emmas and Ellens and Yettas and Evas, and most of them didn’t come out, may their souls rest in Paradise. And now the survivors were dead, too — most of them, anyway. Felder himself had avoided the camps by dint of sheer, stupid luck, having hidden in the linen closet with their maid, Minnie, until the SS had finished rounding up the rest of his family and herding them and others like them into the central square. Minnie, who’d once been his nursemaid, had felt delicious to twelve-year-old Felder in the confines of the warm, fragrant closet, her breasts against his chest, her breath in his face. As darkness fell she’d led him to the edge of town, where she lived in a small, decrepit, sour-smelling flat with her parents, two brothers, three sisters, and maternal grandmother. An argument had broken out in a jumble of Polish and German, the gist of which was that they couldn’t keep him: they’d all be killed. Then Minnie had whispered to her mother that Felder could pass for Christian, and something else he couldn’t hear, and that night he was allowed to sleep in the corner next to the stove and told to pretend he was deaf. They’d think of a cover story for him: he was a cousin, a second cousin even, an orphan of the war.

There was no plumbing in the flat. To get water you had to go to the courtyard of the building and pump it. The neighbors emptied their slop buckets out the window sometimes, especially at night, into the courtyard, where the Christian children ran like wild beasts, braying and hooting into the wind, their pink-white faces going almost blue as the fall changed to winter, until they looked like potato water.

“Black Donkey! Black Donkey!” they cried, pointing at Felder’s thick black hair and chasing him around the courtyard, the bigger boys pulling his trousers down so that the pale blond girls with their pale blue eyes could look at his thing and laugh. “His pecker sure isn’t as big as his nose!” they cried, shrieking insults from house to house until the entire courtyard resounded with them.

Because Felder’s parents were — had been — radicals, he had a foreskin, as wrinkled and sour smelling as any German peasant’s. Socialists who believed that the old religions were dead and that the way forward was through technology and education and a radical redistribution of wealth, his parents had not only insisted on having a civil wedding at city hall, but when their first and only son had finally come along — years after they’d given up hope of ever having a second child — they’d adamantly refused to circumcise him, calling the procedure “barbaric” and “atavistic,” a symbol of all that had held the Jews back, of all that was wrong with Jews and Judaism as a whole. They’d met as students at the university in Mainz, where she’d majored in literature and he in biology. After they were married, they’d taken teaching positions at a provincial secondary school renowned for its progressive policy of educating both sexes under one roof. And there they’d held on to their beliefs in the progress of mankind — until they’d been dragged from their dinner on the Christian Sabbath.

In Minnie’s flat, Felder, now renamed Tim, was moved from the spot beside the stove to a corner next to the washing. The family ate cabbage when they had it, potatoes when they didn’t, and then, as the war ground on and even big towns like theirs fell into desperation, not much of anything at all. Bugs. Roots. Frogs. River plants, which Felder pulled up from the banks, careful not to go in too deep, where he might be swallowed up and drowned, the waters closing over his head.

“Where did you come from, Black Donkey?” the other children yelled, sticking out their tongues and laughing until one of the mothers came down to do her washing at the pump and, curses flying, scattered the children like so much chicken feed. “Brats! Idiots! I’ll flay every last one of you alive!”

One of the mothers in particular was fierce, with a huge bosom, red hair, arms like two ham hocks, buttocks that strained against her dresses, and a tattered sweater — always the same one, black with black buttons — barely covering her chest. Whenever she appeared, the children froze as if in a stuck movie reel and then ran off. Only Felder would remain, too terrified even to run, too terrified to do much of anything other than look at his feet and hope the woman wouldn’t notice him.

“What are you looking at?” she’d snarl.

“Uh-yuh,” he’d stammer, pretending to be deaf, as he’d been told.

She’d return to her work, and he’d slink away only to dream of her over and over as he slept in a sweat of longing in his corner by the wet washing and his penis rose and stiffened and finally burst.

Then the bombs began to fall, and Felder found himself up to his neck in the river and then in over his head and then above the water and then below it again as the reeds took him and the bombs burst until he was scrambling up the bank to the woods on the other side. He was all but dead of starvation, covered with suppurating sores and insect bites, when he stumbled upon the Americans. Then the displaced-persons camps: their jaunty flags and Yankee Doodle dandy. Three years later he was in New Orleans, Louisiana, working on a loading dock. A rich Jew by the name of Bernstein, a cousin of a cousin, had given him a job. Felder wasn’t particularly grateful. He wasn’t particularly angry either. Bernstein kept telling him how lucky he was to have survived.

The dog had come with a name: Goldie. Of course her name was Goldie. She was part golden retriever, so what else would she be called? But from the moment she’d looked at him with her large and luminous black eyes, Felder had known the name was a lie, a stupid and obvious concoction his daughter had given her, thinking it would sound Jewish. No sooner had Goldie come up to Felder and sniffed his feet and legs and crotch and finally his hands than he’d changed her name to Esther. He didn’t need to explain it to anyone, not even to the rabbi: he knew what he knew. And what he knew was that, somehow, baruch Hashem, the dog was a vessel of his sister’s soul.

“Who names their dog after their dead sister?” Rhonda wanted to know. She was a large woman, his daughter, and now that she was on the far end of middle age no longer particularly lovable, even to him. She looked like her mother, Sarah, only without her mother’s grace, dignity, and determination. Felder and his wife had fought bitterly for the fifty-nine years that their marriage had lasted, until one day she’d come home from synagogue with a bad headache and died a few hours later. At first Felder hadn’t known if he was too numb with grief to properly mourn, but as time went on, he’d come to understand that mainly he was relieved. A survivor, Sarah had wakened every night screaming about the bayonets and been, at best, an indifferent mother. Worse, she’d bitterly resented living in Baton Rouge and not New Orleans, where they had met and married, even though it, too, hadn’t been to her liking — too hot, too American, too Catholic, too many drunks, too many shvartzes. And she’d persistently reminded Felder that back in Vienna she’d not only been a typist at Wiener Zeitung but also had been admired by both the paper’s chief opera critic and the wealthy heir of the city’s leading Jewish banking family. Such a beauty she’d been, so feisty, so ferocious, she could have had anyone, but instead here she was, stuck in a small, lousy house in a small, lousy town, and who had she married? An intellectual? An artist? A professional of any sort? No, she’d married Felder, eight years her junior, the uneducated, uncircumcised manager of a shrimp-processing factory. “Thank God my father isn’t around to see what’s become of me,” she’d mutter as she padded around their cramped kitchen, wiping the sweat from her broad forehead and eyes. But she’d had something, some kind of grit, some kind of class that Rhonda lacked. Sarah could give as good as she got, and when she was drunk, she would get misty-eyed and sing in German the songs of her childhood. She was very religious: very frum. She lit candles, sang the Shabbos songs. She was a good-looking woman, too — much better-looking than Felder, who had a long, thin face dominated by an oversized nose, eyes that were set a bit too close together, and hair so thick he couldn’t get a comb through it. Sarah had a perfect oval of a mouth and was padded in all the right places, with a bottom so round and pink it had a life of its own. Now he was nearly bald and so thin that his clothes flapped on him, and she was in the ground. A year after she’d died, he’d sold the house and moved into a one-bedroom apartment on Perkins Road.

Years ago he’d read a story, or maybe someone had told him a story, about a man whose wife is dying slowly of cancer. Every day the wife gets a little sicker. For years the man told everyone who would listen that, once his wife died, he would have nothing to live for. And, lo and behold, one day the wife doesn’t wake up, and the husband takes a gun from the kitchen, loads it with a single bullet, goes out into the backyard, and shoots himself in the mouth. That was quite a story. But Felder didn’t believe it.

“Daddy?” Rhonda said when he didn’t answer. “Have you thought about getting a hearing aid?”

“Why should I get a hearing aid?”

“It’s just that with you living here all alone . . .” She spread her arms wide to indicate his lemon-colored living room, or at least that’s what she called it: “lemon-colored.” It was really more beige: beige wall-to-wall carpet, a beige-brown sofa, and two vaguely beige-orange chairs, stained with age. She wanted him to move into an assisted-living facility on Florida Boulevard and couldn’t understand why he hadn’t done it yet. “What if someone tried to break in on you?”

“So let them,” he said.

“This is serious, Daddy! What if someone breaks in here one night, and you’re asleep? God knows what could happen. It’s happened before, you know. Right here in this very building. Do you have any idea how old you are?”

“Old enough, that’s what,” he said. “And anyway, I have Esther here. You think she doesn’t know how to bark?”

“I wish you wouldn’t call her Esther,” Rhonda said. “Do you have any idea how sick that is?”

“I don’t think she minds,” Felder said, scratching Esther between her ears. “Do you, girl?”

Esther wagged her tail.

The truth was he didn’t remember all that much about his sister. Mainly he remembered the way she’d smelled: like baking potatoes mixed with some elixir that he’d always thought of as a byproduct of her life in the city. When she was seventeen, she’d gone to Berlin to study in the university there, and whenever she came home to visit, she brought with her not only books and friends and excited talk about Schopenhauer and Schelling, but that strange, alluring scent. She was beautiful — that, too, he remembered — with long, thick black hair that she pulled back into a bun and very white hands. She fought with their mother about some boy she was seeing in Berlin, a boy who wasn’t Jewish. Emil, that was his name. “Why do they care who I see?” she haughtily declared to Felder, tossing her black hair, brushed and loose for bed. “Hypocrites, the both of them!”

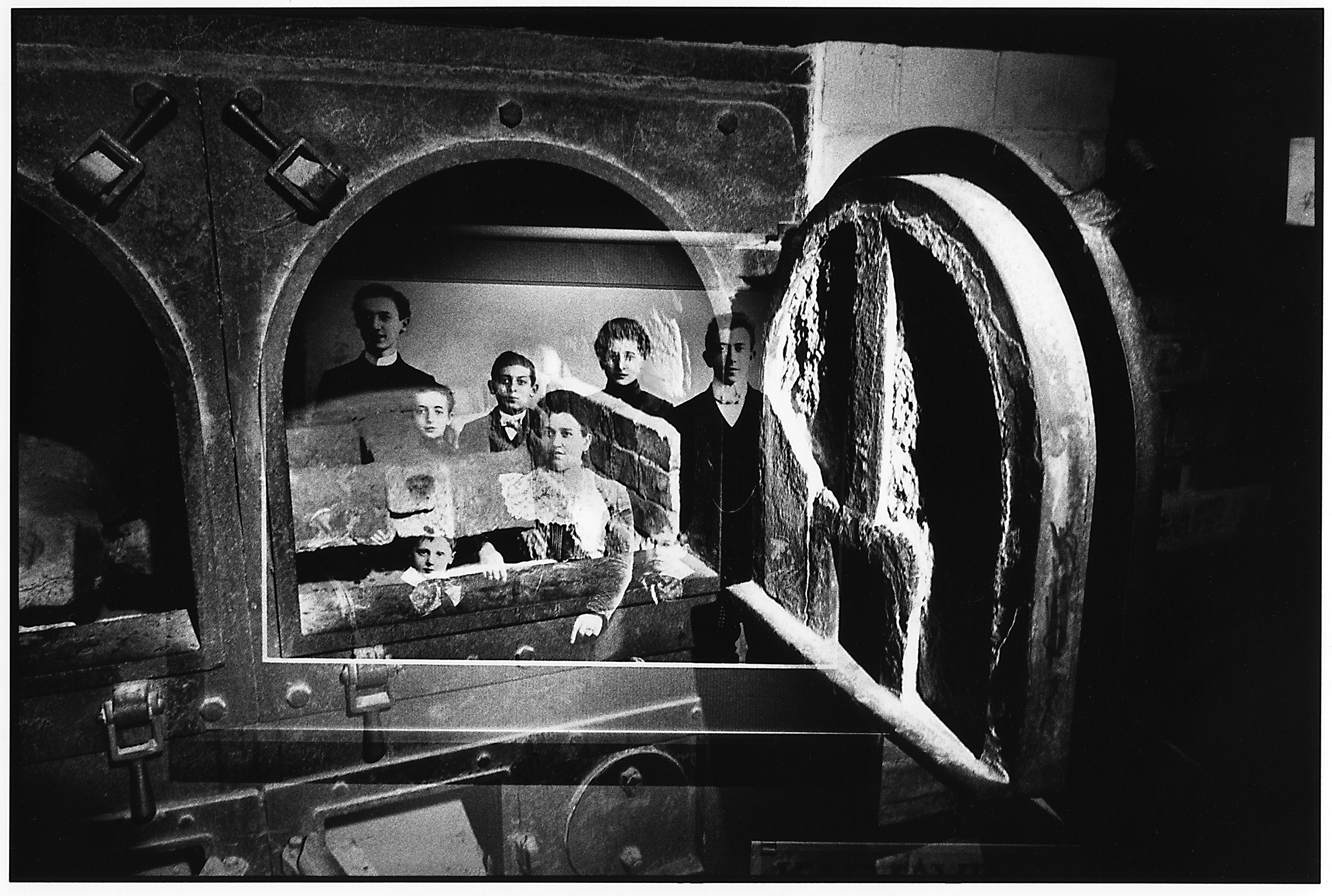

Why did Felder remember that moment and not the countless other minutes, hours, days that he’d spent with her: at breakfast or dinner, or walking to school, or watching her choose her clothes for the day ahead, laying them out on the desk chair in her bedroom? He just did, that’s why. That’s all he had of her, too, because once she’d been taken to Bergen-Belsen, that was it: he’d never been able to trace her further, to find out whether she’d been gassed or had merely died, as so many had, of starvation, or disease, or bullet wound, or execution of another kind, in a pit or in a forest. Or had she been raped? Raped and then murdered? She’d been a pretty girl, his sister — a beautiful girl. Had some Nazi forced her and then pushed her into the gas chamber?

He didn’t like to think such thoughts and tried his best not to. Even so, they came to him uninvited at all hours of the day and night. Sarah had been plagued with such nightmarish thoughts as well. He could always tell when she’d had a particularly tortured day, because there would either be no dinner on the table or so much food they’d be eating leftovers for weeks.

It was a miracle they’d managed to have children at all — first Rhonda and then, a year later, Kate. Sarah thought the name Kate sounded more American than Rhonda, which had been Felder’s idea. Kate lived in Atlanta now and only came to see her father when she had to; they’d never really gotten along. But her birth had been a miracle — both girls’ were. To make love, to have someone to hold and be intimate with, to kiss and grunt and moan and then, after all they’d been through, after all that their bodies and souls had been deprived of — food and water and warmth — after they’d been battered and exposed to humiliation and deprivation, to watch Sarah’s belly swell up just like any other woman’s: such was the way of the world. He couldn’t have cared less about the sex of the babies. He’d merely marveled that they were there, in his house in Louisiana — four thousand miles and a million years away from the ruination of wartime Europe.

Two months after her arrival, Esther began to speak to him in Yiddish. At first Felder assumed he was dreaming — either that or he’d suffered some kind of stroke, or he wasn’t in his right mind, or his neurons were misfiring and his synapses collapsing. Or perhaps he was merely willfully hearing what wasn’t there: her rrurffs and arrrs sounding, to his delusional ears, like Di Rusishe ongeyn — the Russians are coming! — as if his parents’ dreams of a socialist paradise might sweep the Nazi contagion away.

He patted Esther’s head. “We’re in America now. It’s OK. Go back to sleep.”

Tsu vartn!

“What did you say?”

Schlump! Shmegegge! Shmendrik!

It was odd that she insulted him in Yiddish, because at home they’d mainly spoken German, the language not only of literature and the Enlightenment but also, of course, of university-level studies. Both parents also spoke some Polish and some Ukrainian, but not enough, they said, to really carry on a conversation — or, at least, not at an elevated level. Felder’s grandfather, a grain merchant, had wanted Felder’s father to be a lawyer. The older man had all but cut his son off when he’d gone into teaching. And then, when Felder’s father began handing out leaflets and attending rallies for the Socialist Workers’ Party, Felder’s grandfather had suffered a heart attack and died.

Usually Esther slept on her doggy pillow in a corner of Felder’s bedroom, but after she started barking in Yiddish, he invited her to join him in the bed. After all, there was plenty of room — all of Sarah’s side, plus spare room on his own; even after decades of living in America, he couldn’t stop sleeping as if he were curled up in the corner next to the dripping wet laundry.

Bounding up, Esther licked his face, and then she fell asleep and ran in her dreams, her dainty paws padding against the blanket.

It was nice having someone to talk to again, someone who understood, who’d been there, who had, in point of fact, known him since birth. It was also awkward at first. After more than sixty years of separation, where did you start? Small talk seemed idiotic, but going right to the big questions, the big unknowns, the terror of the war years, seemed downright rude. So they struck an unspoken bargain to start with the present, with his two daughters: Rhonda in her giant house in Bocage, with a kitchen that was bigger than his whole apartment and a swimming pool that she didn’t swim in; and Kate in Atlanta, working with mentally disabled children, teaching them how to paint. Both daughters had grown children of their own, and lazy American husbands. As for Sarah — well, what could he say? They’d met at a time when neither of them could quite believe that they were still alive, and within days they had agreed to marry. Neither had any living relatives (none that they knew of, anyway), and on their wedding night, rather than fall into the delights of bride and groom, they’d clung to each other, fearful and crying, like small children during a thunderstorm. Only later, once they’d gotten used to each other’s ways, once they’d each learned to trust that the solid, foul-mouthed Americans they met at the grocery store meant no harm, that their smiles didn’t hide menace, that their accents betrayed only where they’d been raised, did Sarah and Felder become entwined in each other’s bodies. They were all over each other like starving beasts in winter. As he kissed her mouth and lunged for her breasts, Sarah would babble in a mixture of German and Yiddish and Russian and Polish, saying unspeakable things, wretched things, perverse things, things no whore could conceive of. And he, engorged and excited, rose up like the beast that he, too, had become, with strong shoulders and skin made dark by working on the docks. Then, in the morning, they’d rise and dress without talking or even looking at each other. At night, before falling into bed, they fought.

“And that’s how we got the girls,” he explained.

Ye, gut.

“And when she died . . .” He shrugged, palms turned upward, allowing the heavens to complete his sentence.

By this point Esther didn’t need a leash. He could trust her to walk by his side, neither in front nor in back of him, and he had to be on the alert only in case a bicyclist came up too fast from behind them, which could scare her and make her dart between his legs. It was hard for Esther to get used to the traffic and the noises in Baton Rouge. Who could blame her? What kind of person, raised in a provincial town in Germany and then killed by the Nazis, could so much as fathom the tangle of roads with their roaring, beeping, honking, exhaust-spewing vehicles, the rap music and country rock and Christian contemporary blaring out of every other car and truck? Even in City Park, which was his favorite place to walk her, there were teenagers on rollerblades and students on bikes. And the pickup trucks — you’d think after almost a lifetime of living in Louisiana, Felder would have gotten used to the trucks outfitted with giant wheels or gun racks speeding down the highway, but he never did. To him they felt threatening.

“What about you?” he asked, as Esther sniffed around one of the public trash cans that lined the walking path in City Park.

“Trust me, you don’t want to know,” she answered, this time in proper Berliner German.

“But I do want to know about you. I’ve never stopped wanting to know about you.”

“Well, for one thing, I’ve been dead awhile now.”

“This is news?”

“Wise guy. You think I traveled through time and space and consciousness itself for your smart mouth?”

But he knew she was kidding — not only from her tone of voice but from the fact that her tail was wagging.

It had always bothered Felder when his daughters would press him for details about his life in Germany during the war: about how he’d survived, what he’d eaten, and if he’d seen any dead bodies or heard Hitler’s speeches on the radio. So he hadn’t told them any details. And why should they want to know, anyhow? What had happened back then was a phantasm, a hideous example of humanity’s worst inclinations, worse even than what the Romans had done, worse even than Nebuchadnezzar, Pharaoh, and Stalin combined. Sarah had likewise maintained her silence, only once revealing the worst moments of her own ordeal: the way couples had copulated openly in the refugee camps, the way the kapo had twisted her nipples until they bled. But she’d been feverish then, raving; the stories had come in broken phrases and mixed languages, running together. And as for his family — his mother, his father, his sister, his aunts and uncles and grandparents and cousins — he’d had no idea what had become of them, only that they were gone. At first when the news of the Nazi atrocities floated across the ocean, shocking the smuggest of the smug American Jews, with their comfortable homes and big steak and roast-chicken dinners, their Christmas trees and dances at the country club, he’d gone in search of answers. Well, not in search. Not literally. He’d placed ads in the Yiddish papers in New York. He’d written letters — copious amounts of letters — to embassies, to the UN, and once even to the famous Nazi-hunter Simon Wiesenthal. He’d contacted the International Refugee Organization, which had referred him to the Red Cross, which had given him the only piece of information he had about his family: that his sister had boarded a train bound for Bergen-Belsen in the summer of 1943. Then, in the early sixties, when that butcher Adolf Eichmann was tried and executed in Israel, Felder stopped reading the papers, unplugged the TV.

“You weren’t even a little bit curious to watch?” Esther asked when he took her for a walk one afternoon before the rains came. Esther was afraid of storms. At the first distant rumblings of thunder, she would cower in the corner, hide her eyes under her paws, and give off a slightly sickening odor. It had taken some getting used to on Felder’s part, too — the way, in the late afternoons, the entire sky would turn a greenish gray, and the wind would pick up, and, just like that, the entire world was wet. Wet as if it were the heralding of the biblical flood. Wet like being submerged in that river. But, then again, everything in Louisiana had taken some getting used to: half-naked black men shining with sweat; plump prostitutes from Caribbean islands who spoke a mixture of French and English and called him “Jerry,” because they thought he was German; the heat; the dust; the snakes; the lizards; the humid, heavy air; the Jews who didn’t act like any Jews he’d ever met before, neither embracing the working-class dream of equality for all, nor intellectual pursuits, nor God Himself, but rather going about their lives in utter obliviousness to the great pulsing linguistic and theological and moral struggle that was Judaism, that was Jews themselves. They spoke with Southern accents and ordered their black servants around; they decorated their large houses with yards of English fabrics as they sipped their iced tea and their mint juleps and fretted about golf and Mardi Gras. But a Jew like he was — a Jew without religion and yet as steeped in Judaism as his own grandparents had been, as blanketed and smothered by it as if he’d been raised in a shtetl, unable to leave it and equally unable to sink into its embrace — they’d never met such a Jew. “Sorry for everything that’s happening over there,” they might say, or, “You must be mighty happy to be in the States.” They were generous, too. They invited him into their homes and their synagogues, helped him find a better job. But they didn’t understand. How could they?

“You haven’t answered my question,” Esther continued, nipping gently at his heels to get his attention.

“Sorry,” he said. “What question?”

“About Eichmann, that slaughterer.”

Felder shrugged. “Why should I be curious? I knew he was guilty. The whole world knew he was guilty. I didn’t want to watch this man getting a proper trial, a law-and-order trial, a fair trial. His hands stained with the blood of millions, and he gets the best lawyers money can buy.”

“Is that true?”

“German lawyers, of course. And the Israeli government had to pay their fees. How could you not know that?”

“It’s limited, what they let us know once we’re dead. They allow us to have intimations, but only now and then. . . .”

Felder wasn’t listening, not really, because he was thinking of how irritating it had been for him and Sarah to be survivors in the first place. Because of it, they’d had a certain celebrity status, after every kid in Baton Rouge had to read The Diary of Anne Frank in school and even the local newspaper started sponsoring a Holocaust Remembrance Day essay-writing contest for students. Baton Rouge’s two main news outlets had called for interviews with Sarah and him, and goy priests had begged them to talk to the youth. It had made Felder sick: talking about what had happened to his sister and his parents and his schoolmates, about the corpses of children and old people hanging from the trees and the black flies swarming in their eyeballs. Was it, they asked him, a lot like racism in the South? Please. He’d wanted to vomit.

“I’m tired of having survived,” he said.

The phone rang. It was Kate, the younger of his daughters. She was worried that he wasn’t taking proper care of himself.

“I’m fine,” he said.

“That’s not what Rhonda says.”

“What does Rhonda say?”

“Rhonda says that, for starters, you need to get your hearing checked.”

“My hearing’s fine. I can hear you, can’t I?”

“Daddy, I’m shouting into the phone.”

“Well, I can hear you.”

“And what about the dog?”

“She’s a good girl, Esther is.” Hearing her name, Esther got up from her place by his feet and lowered her head onto his lap.

“Rhonda says that you talk to her.”

“So what?”

“Rhonda says that you have long conversations with her.”

“I’m old. I’m allowed to be eccentric.”

“That’s exactly the point, Daddy. You are old. And you’re lonely. Why are you living in that cramped apartment when you could have a better apartment in assisted living, where you wouldn’t have to cook for yourself, and where you’d have some company? I just don’t understand.”

“I have company.”

“Who?”

“The rabbi,” he said. “The new one. Kaplan. That’s who. All the time, he visits.”

“Kaplan was the rabbi when I was growing up.”

“This one is Kaplan, too.”

“For your information, his name is Kaminsky. Rhonda talked to him yesterday, and he told her that you refuse to see him.”

“Kaminsky, Kaplan. At my age I confuse names.”

“Rhonda says that’s not all you confuse.”

“You girls have been talking about me.”

“We’re your daughters, Daddy, and we love you. Of course we’ve been talking about you. Ever since Mom died—”

“This has nothing to do with your mother.”

“You may not think so, but since her death you’ve been acting stranger and stranger. You never even go to synagogue to say kaddish for her, which, may I remind you, is what we do to honor our loved ones who have passed.”

“She died, is what she did. ‘Passed’ is what you do with a kidney stone.”

“The point is, you’ve isolated yourself from the community.”

“What community? All my friends are dead.”

“That’s what I mean. It isn’t good for you to live alone. And, frankly, it isn’t safe.”

“It’s perfectly safe.”

“Rhonda said there was a break-in at your complex a month ago, and three last year alone.”

“So what? They want my TV? They can have it.”

“At least get a burglar alarm, OK?”

“You worry too much,” he said.

Eventually Esther filled him in on the last few months of her life: She’d moved into her boyfriend Emil’s flat in Berlin and pretended to be his sister until they were both taken away — him to the police station, her directly to the depot. By then she’d missed two periods in a row and knew she was pregnant, though she wasn’t showing yet. At the time she was gassed, her belly was just beginning to round outward, and she’d held it, weeping, until she was no more. “I was going to name it Ruth if it was a girl,” she said. “And Joseph if it was a boy.”

“For me?”

“Of course for you. Who else? I figured you were dead, too.”

Not that she’d really thought she would be able to carry a child and then give birth to it in a concentration camp, not with the starvation, the filth, the daily rounds of death. Sometimes she’d prayed to miscarry. At night, just before she fell asleep, she’d beat her belly, thinking that if it could come out — if it might slip out between her legs in a knotty gush of blood — she herself might escape notice, might even be strong enough to endure. Other times she prayed only that her death might come soon. In the end both she and her baby had died, and her baby’s soul was still waiting for another chance to be born.

“So reincarnation is real, then?” Felder said.

“It’s not that straightforward,” she explained. “It’s more like — the human idea that people vanish isn’t accurate.”

“Oh,” he said, but mainly because he didn’t want to leave an awkward pause hanging in the air between them.

As their conversations got longer, so did their walks. At first Felder had confined himself to City Park, but now he and Esther did at least one trip around the golf course, and sometimes they even went as far as the I-10 underpass. Although Felder explained that the roaring traffic overhead couldn’t possibly hurt them, Esther would sit on her haunches, trembling, and downright refuse to cross under the highway with him. Nor did it matter to her that on the other side were yet more vistas: of the university campus on the far shore, and egrets and pelicans and ducks. “You’d like it,” he’d say. “And you don’t even have to walk on your own four paws. I’ll carry you.”

“Thanks, but no thanks.”

So adamantly did she refuse that, the one time he tried to scoop her up against her will, she bit his wrist and ran in the opposite direction. Of course, she stopped at the bend to wait for him.

“You don’t trust me,” he said, angry.

“Trust has nothing to do with it.”

“Even so, I’m alive, and I live here, and highways and cars are something I know about. And still you don’t trust me.”

“I don’t trust anything or anyone,” she said.

“Why did you even bother coming here, then?”

“To tell you the truth,” she said, “it was God’s idea, not mine.”

That gave him something to think about, because even with his miraculous escape and his having had work and a wife and a family and a house and a community in Louisiana; even with the knowledge that his five grandchildren had been raised as Jews and would, most likely, have Jewish children of their own; even after Esther herself had come to him and filled him in on everything that had happened; even after all that, he hadn’t believed, let alone trusted, in God. But then something began to change in him. He thought maybe there is a God after all, a God who somehow pervaded the universe in a way beyond anything Felder could so much as intuit; a God who was in his cells and in his pores and in his sweat and in his shit; a God who had come spurting out of his uncircumcised member when he’d climbed on top of or lain under Sarah and thrust life into her womb.

It was with this thought on his mind that he woke one night to Esther’s frantic barking. “What is it?” he mumbled in Yiddish, to which she replied, also in Yiddish, “A thief!”

She darted into the beige living room, barking, with Felder following after, tripping slightly in his too-big pajama pants, banging the little toe of his right foot against something — a table leg? — as he tried to keep up with her. He cursed; she howled. Everything was dark. Then he heard something fall over, followed by the sound of throaty breathing.

“Motherfuck!”

A moment later whoever it was was gone, and Esther was on Felder’s lap, the two of them together on the sofa.

The next day he had to call the building manager to get his door fixed — the lock was broken; the chain, too — and the day after that, both Kate and Rhonda appeared at his door, saying that they would no longer allow him to live where he was, that he was in danger there, but he was also in luck, because the assisted-living facility on Florida Boulevard that had been Rhonda’s first choice for him and that was almost impossible to get into had an opening. One of the residents was moving to South Carolina to be closer to his son, and Rhonda had already put down three months’ rent on the vacant apartment. It was Felder’s as soon as he was ready to move.

“You did what?” he said.

She explained again.

“I’m sorry,” he said, “but I’m not moving. I like it here.”

“Essex Homes is the best in the business,” Kate said. “Do you have any clue what kind of strings we’ve had to pull, how many hours on the phone we’ve put in to clinch this apartment for you?”

“So who asked you to?”

“Actually,” Kate said, “you did.”

“Ha!”

“Show him,” she said.

At which point Rhonda reached into her oversized purse, brought out an oversized envelope, and showed him a copy of some legal document that he had signed. It was, she explained, a power of attorney, granting her control over any legal or financial decisions made in regard to his welfare.

“You really don’t have a choice,” she said.

And now he remembered how, in the confusion over selling the old house, he’d allowed his daughter to take over not only with the realtor, a dyed-blonde named Judy or Jody or Jennie — one of those J names — but also with the bank and the closing lawyer and others. He remembered how she’d sat him down one day and explained to him that, when he signed the paper, he would in effect be handing over the right to make important decisions to her. And what had he done? He’d nodded and said, “Yes, yes. I understand. I’m not senile, you know. Not yet, anyway.”

He didn’t even really care about staying in the one-bedroom apartment. It was just that he didn’t particularly like old people, never had. It was bad enough that Sarah had grown old; worse still that he had. Old people tended to be ugly, and to have bad breath, and to enjoy prattling on about the past and showing you pictures you didn’t really want to see of their grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Who needed them? Certainly not him. Plus he hated being bossed around, particularly by his own daughters.

“No,” he said.

The girls looked at each other in a way that reminded him of their mother when she was about to start shouting.

“Really, Daddy,” the younger of the two — the one who had never even pretended to understand or respect him — said. “You don’t have a choice. It’s all arranged.”

That’s when he knew they’d beaten him. He hung his head. He squeezed his eyes shut. He opened them again and, as Esther rubbed against him, said, “Looks like we’re moving, Esther.”

“Except, Daddy?” Kate said. “That’s not going to work.”

“What?”

“Essex Homes doesn’t allow pets.”

“But don’t worry,” Rhonda said. “Esther is coming home with me, and you can see her as often as you like.”

An hour later, as Felder and Esther walked toward City Park, he said, “Don’t worry. I wouldn’t let you go to live with Rhonda in a million years, no matter how big that palace of hers is, no matter that she has a television set bigger than the dining-room table at home. You remember that dining-room table, how Mama and Papa used to argue about politics there? Even if she takes you to the doggy beauty parlor every week to get your fur shampooed, I won’t let her take you away. No! Over my dead body. They think they can just do this to us, but they can’t. Who do they think they are? God in heaven, what am I going to do? Oh, Esther, Esther! What are we going to do, Esther?”

“Arf,” she said.

“What?”

“Arf,” she said again.

Then he heard the sound of a cyclist coming up from behind them on the bike path, and then the bike was swerving around them on their right while, on their left, a car came speeding up the hill, music blaring from its open windows, making the air shake and causing Felder to feel a sudden unpleasant sensation in the hollows of his bones. The next thing he knew, Esther, scared and skittish, darted into the road, where, before his eyes, a second car coming from the opposite direction squealed and skidded but hit her just the same.

“Esther!”

Felder ran into the street and, bending over, saw that she was badly hurt, that she was bleeding from her eyes and ears, that her breaths were agony, that she was dying. Behind him he heard someone say, “Oh, no. I’m so sorry, man. I braked as hard as I could,” and someone else say, “Yo, someone help the old dude. It looks like he’s going to faint,” and a third person say, “Does anyone have any water?” But they were as nothing to him, and he refused their offers of help. He sat down in the road and pulled Esther’s body onto his lap, stroking her face as his tears fell on her muzzle and into her terrified eyes. And even after she’d stopped breathing, he held her limp body and wailed over her as, one by one, more people came to help, and the crowd surged around him, and he stood over Esther’s body to say kaddish while the other mourners rocked back and forth endlessly.