It’s already sweltering at sunrise on this August Sunday morning in Norfolk, Virginia. My Lebanese grandfather is taking my brother and me fishing for blue crabs on the Elizabeth River. He stands on the dock and drops the oars into the flat-bottomed rowboat. The morning light is greenish, the canal the color of Turkish coffee. At the dock’s fish-cleaning station, water dribbles from a hose, and the heads and guts of game fish collect in bins to be toted away as fertilizer for gardens around Norfolk and beyond.

A sprinkler system comes on at my uncle Gerard’s house behind us. A lawyer, he is the only member of my family with real money, and a while back he made the mistake of talking vaguely about the relatives getting together at his place on weekends. That’s all it took for the rest of us to start showing up with brutish regularity. Inside the house adults are sleeping on couches and chairs and islands of carpet, plastic cups of diluted liquor nearby. The ashtrays are full of crushed Marlboros — menthols for the ladies. It’s 1977, and I’m eleven years old.

Gerard, who recently made partner at his law firm, collects boats, each one bigger than the last. Lebanese and Syrian immigrants from around Norfolk also haul their small crafts over to his dock and tie them up. They don’t even ask first. A little fishing village of painted skiffs has sprung up, and the neighbors aren’t happy.

There’s been some sort of falling out between Gerard and my grandfather: my uncle wants to sell a piece of land, and my grandfather is against it. The two don’t speak to each other this morning as they move about the dock. Gerard is preparing to go fishing, too, but not with us. He and my father and two other men are equipping a motorboat with an outboard engine for a trip to Lynnhaven Inlet, just offshore from the bustling Virginia Beach strip, with its traffic and crab shacks. Gerard’s big boat, the Miss Justice, has a blown head gasket and lists in the water, out of commission, the engine cover off and slicks of oil floating beside it. The men are having trouble fitting all their gear on the nameless aluminum motorboat with a dented bow. Overloaded with fishing poles and tackle and too many coolers, it hardly looks seaworthy.

Earlier my father was sent to the 7-Eleven for ice, and he came back with two twenty-pound slabs. Now a Lebanese man I call Uncle Billy (though he’s not my uncle, and Billy’s not his real name) says he wanted shaved ice, and he berates my father, who shrugs it off and grins up at my brother and me on the dock. Billy, who has dark eyes and a wolfish face, produces a flat-head screwdriver and begins hacking the ice into pieces. They are all balding in the fashion many Arab men do: a circular patch that grows slowly over the years. You might think they were Italians if you didn’t know them, and they wouldn’t mind being mistaken for Italians — all except for Billy, who’d take out a napkin and sketch a foreign coast to show you exactly where he is from.

A cigarette hanging from his lips, Billy yanks the starter cord of the twenty-five-horsepower Mercury outboard and tells everyone on the boat to sit down. The fourth man with them, Uncle Joe, has the pleasant, round face of a rural magistrate and drinks from a plastic cup filled to the rim with Canadian whiskey. Who are they, anyway, these men I call my uncles? They are valets, bouncers, deliverymen, poachers of small game, welders, and hustlers. Only my father and his brother have educations. The others have accents.

The Mercury engine clicks and coughs and turns over. Billy has been up for three days straight, says Uncle Gerard, who is busy rigging a huge bucktail lure on a rod. He talks enthusiastically about catching striped bass, but striped-bass populations sank into decline years ago. I’m eleven, and even I know this. There’s been talk of shutting down all fishing during the spawning season, so that if a pair of striped bass do show up, they’ll be able to mate in peace. The whole Chesapeake Bay is experiencing a lack of striped bass, and it’s only 1977, for God’s sake. Just think about that for a moment while the motor warms and the blue smoke curls from the exhaust.

Satisfied the engine will take them to Lynnhaven Inlet and back, Uncle Billy looks at my father and says, “Seasick already.” Then they’re off, pulling away from the dock and motoring past the abandoned duck-hunting shanties, a frothy wake creating waves that slap against the pilings and bulwarks of houses owned by lawyers, businessmen, politicians, couples who sell real estate, and one tycoon who made his fortune in shellfish. Before they round the bend, I catch sight of my father balancing awkwardly on a cooler, trying not to look completely miserable. I worry inexplicably that I’ll never see any of them again.

“Fools,” says a voice behind me.

It’s my grandfather’s brother, L.T. Zoby. Everyone calls him “Two Bathroom,” because he has two, unlike most of us. A plumber by trade, he pioneered the sale of custom fixtures to wealthy homeowners in Norfolk and Virginia Beach. He can drive by a condemned house and figure, with astounding accuracy, how much it would cost to fix it up and make it into a paying rental.

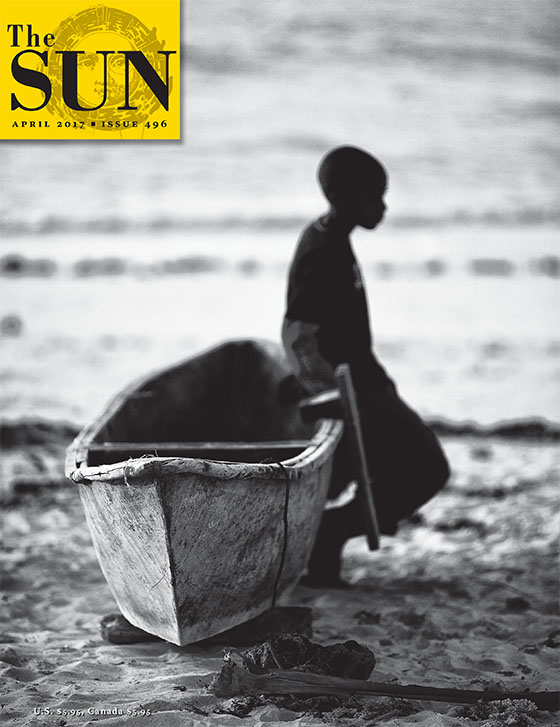

Two Bathroom isn’t going fishing today. Instead he and his wife will sit in canvas deck chairs like royalty, an oscillating fan brought outside to cool them on this scorching Tidewater morning. Turkish coffee will be served hourly on trays — out of nowhere, it seems — always with cube sugar and cream that no one touches except the flies. Two Bathroom gets special treatment because, as a plumber, he’s useful in ways many of the Arab men in Norfolk aren’t. No one ever imagined he would make anything of himself, but here he is, a Cadillac in the driveway and a son in college. An Irish Catholic wife, even. He has come down to the dock to bring my grandfather a brown-bag lunch: onions and grilled eggplant on flatbread. My grandfather sets the oars in their brass locks. The old rowboat’s paint is peeling, and it has no frills whatsoever, not even a proper anchor, just a cinder block tied to a rope. My grandfather makes my brother and me wear huge, ridiculous life jackets. He has a bushel basket to hold the crabs we catch and two dip nets on long poles to scoop them from the water. We have a bag of fish heads he collected earlier in the week to use as crab bait. Our lines are made of garden twine with spark plugs for sinkers.

With a few powerful strokes of the oars, we’re underway. The canal water is so dark it’s almost black. Rafts of pine needles and cottonwood wool gather in eddies. Every pier we pass is covered with barnacles and encrusted with mussels. The water stinks in a dank, rotting way. A few more strokes with the oars and we turn the corner and see the open Elizabeth River for the first time. My grandfather drags one oar in the water and pulls with the opposite one, making a clean turn.

He believes in fishing for at least one change in tide — all the men do: if you can’t stay out that long, why bother? When we reach a good spot, he drops the cinder block. I watch him let out maybe ten feet of line on the anchor. I feel the tide beneath the boat, the pull and push. These cycles, when talked about by the Lebanese and Syrian fishermen who still remember the Mediterranean, seem magical to me. No one I know questions the value of tides, or the wisdom of abiding by them. Night fishers, jug-wine aficionados, these men regard tides as indisputable, like the dates of certain wars, the rules for vehicle registration, the loans required to purchase land.

My grandfather forces the fish heads onto metal clips at the end of our lines and tosses them carelessly overboard. When he has five or six lines out, he wipes his hands with a rag, opens a Mason jar of tap water, and takes a drink. There are no seat cushions, just hot aluminum benches. If you want to change seats without burning your thighs, you must dip the net in the river and drip water on the metal first. My brother has already had enough. He is lucky that he has our grandfather’s dark skin. He doesn’t burn. I’m not so lucky.

To break the silence, I harass my grandfather with questions. How deep is the river? How far out will Uncle Billy take the others? Are there really any striped bass around? He wears a fedora, not as a fashion statement but to keep from getting any darker, a constant goal for all the Arabs: don’t get any darker. Billy is the only one among them who has given up on the idea of climbing the social ladder. He bikes around Norfolk and Virginia Beach on a refurbished ten-speed with no hat, no shirt, and no shoes, a cigarette pinched between his teeth. Darker than the rest, he has no wife, just a dog that snarls if you get too close. He wears a ring on his right hand, and if you ask him, he’ll tell you he is married to the sea.

My grandfather, sitting back in the rowboat, says striped bass are pretty much extinct. There’s no regret to this statement. He describes how he and Uncle Billy played a part in their demise, catching fish by the hundreds, some weighing close to forty pounds, huge “hens” (females) bulging with roe. He says it was the best-tasting fish in the river. You cooked it with the skin up so that the meat broiled in its own juices. Maybe a squeeze of lemon, a sliver of onion. White wine, butter. Striped bass were the best. But I’ve heard him say this about flounder, too, and puppy drum, and gray trout. They are all the best.

While we talk, two of the lines go taut, and my grandfather takes the dip net in his hands.

“You’ve got bites,” he says.

My brother and I seize the lines and begin to haul them in, but I am eager and pull too quickly. My line goes limp. My brother, however, coaxes a large jimmy crab — a male — to the surface. He looks enormous, his greenish back nearly a foot across, his claws white and blue with slashes of red on the tips. My grandfather slides the net underneath and deftly nabs the crab, who kicks his legs madly. My grandfather flips the net roughly over the bushel basket. The crab rears up and waves his weaponry at us. There is no way for him to scramble out, but I keep thinking he might. He is ferocious, his freedom snatched away by our rude tactics. My grandfather dips a washrag in the river and covers the crab with it, then sets the lid so that it shades half the basket. He says they “go to sleep” as long as you keep them wet and cool. My brother thinks he means they die, but our grandfather corrects him: “They don’t die until you put them in the cooker.”

All day we catch jimmies, along with some female crabs and a few small peelers — crabs in the process of molting, which my grandfather says he’ll use for bait. Nothing we catch gets released; there’s a use for everything. When the tide has finally come and gone, we have nearly three dozen blue crabs for the steamer. A black mother duck paddles by, hugging the bank with her brood of ducklings. My grandfather makes amused quacks at them, but I know come fall he’ll kill them all if given the chance. The men in my family seem to be like that, ready to take whatever they find. We’re like beachcombers, always looking for something valuable to wash up at our feet, the pitiful hopefulness of recent immigrants — though my father is a bit different, and my skinny brother sitting beside me is, too. He lifts the bushel basket and frowns at the jimmies. I can tell he is thinking of setting them free.

My grandfather pulls up the anchor and shows us how to row. He spins the boat around and starts it forward, not splashing with the oars but slipping them into the current, sort of how a blue crab swims. He even tells us to row like the crabs. He stands in the boat and pees over the side without the slightest fear that he might fall out. Then he tells my brother and me to take him home. He steps around us, the boat tilting dangerously, and sits in the stern, where he pulls his hat over his eyes and pretends to sleep on the hot aluminum.

Sitting side by side, each of us grabs an oar, and my brother and I hack away at the face of the Elizabeth. We start to get the hang of it, rowing together, letting one oar drag if we want to turn in that direction. My brother suggests we just float there, seeing where the river takes us. The tide is cresting, and sure enough we start to drift back toward the landing, past houses with chirring air conditioners that strain to combat the heat. The cicadas are doing their best to broadcast the sweltering temperatures. My brother leans back and pretends to sleep, too. And then it’s just me and the river and a blue heron that stands along the shore, as still as a piling.

Back at Gerard’s house I wonder how the run to the Lynnhaven Inlet is going for the overburdened boat of Arab fishermen. At eleven I have never been on such a trip, but when I am older, I will be invited along, and this is what often happens:

The men drink too much. There are arguments and terse criticisms and inside jokes. Catch limits are surpassed. Limits are just vague notions anyway, part of a different world, like the slim, suntanned women laid out on Virginia Beach, the hotels the men will never stay in, the Corvettes rolling slowly up and down the strip.

Flounder must be fourteen inches or more, but the men keep many that aren’t. They might even catch a small sand shark and keep it for no other reason than to torment my father, throwing it in the direction of his feet, where it twists in agony at the bottom of the boat. My father’s biggest concern is that the shark is being sacrificed for the sake of a joke — no one will eat it. “It pees through its nose,” says Billy. But my father doesn’t have the courage to grab it and toss it over the gunwale. Maybe he almost does, once. He thinks it’s stupid, all of them drifting to sea in the boat, no one less than half drunk, crazed Billy in charge. But he keeps these thoughts to himself, sharing them only with his wife once he is safely ashore.

When the men come in, I am waiting at the dock. I’ve been there for hours. The motorboat seems to be listing dramatically. Uncle Joe pees off the side, waving his cloth hat over his bald head. The Mercury is causing a wake in a “no wake” zone, disturbing the neighbors, who predicted that home values would plummet after the Arabs moved in.

Though Billy is the captain at sea, Gerard takes over once they come ashore. The women have been cooking for hours. There are stuffed eggplants, green peppers, and a stew of rice and tomatoes. Grape leaves have been blanched, then filled with a mixture of lamb, rice, and something else. There’s raw kibbeh so impregnated with onion and black pepper that no flies go near it. My grandfather rinses the jimmy crabs in a pot of fresh water. My father dresses and cleans a cooler of fish, the sequin scales finding their way into his curly black hair. He tears through them, efficient, grimacing while he works. He hurries because there are so many, and he worries the game warden will come along.

“The cops have their hands full with the druggies over on the beach,” says Gerard. But my father worries anyway.

A table is set up outside, and dishes are brought from the kitchen. Gerard goes inside, and a few moments later rock music rips from outdoor speakers: “Fly Like an Eagle” by Steve Miller; “Hotel California” by the Eagles; Rod Stewart, because Aunt Karen has tickets to see him in a few weeks at the Hampton Coliseum. Some other men arrive with brown bags and a white girl who seems dazed by something other than the relentless sunlight. I note the thin white lines from her swimsuit straps on her shoulders, her pink flesh. Some of the Arab men who didn’t go out on the boat today sway to the music. They are absurdly overdressed, smelling of cologne and loneliness, loud gold necklaces on their chests. My father says they travel with silk dress shirts in their cars so they can change into fresh ones between parties. The young Arabs try to get Gerard to dance with them, but he waves them away and smokes a cigarette instead. My mother begins to dance, which causes the young Arabs to excuse themselves with crushing politeness.

“They’re Arabs. They don’t dance with women,” says my older sister, Elizabeth.

“Oh, I always thought they were Portuguese,” says my mother sarcastically.

And so it goes for hours: drinking and laughter, platters of food arriving and disappearing back into the kitchen. You keep your plate and silverware, wiping them off with clean towels between courses. Just when I think the party is winding down and we can load up in my father’s station wagon and go home to Newport News, they clear the table and cover it with newspaper and dump a pile of overspiced steamed crabs in the center. The music continues: “Best of My Love” by the Emotions. High on jug wine and whatever else, everyone begins to dance, even the young Arabs who dress so self-consciously; who don’t risk their clothes by eating seafood but stand a few feet away and speak shyly to each other; who will leave early to make their own party at the beach. My sisters jump in, and my father and mother. Gerard is passing a brown bottle of something back and forth with Billy, who’s not a dancer, but just this once he jumps up and joins the action, no shirt, cigarette dangling, drink in hand. He writhes as if his body has been cast into the sea. Eyes closed, he sings in Arabic, not along with the Emotions song but some other words that have to do with leaving his homeland and ending up a forty-five-year-old bag boy. The stars he is looking up at are not the ones the rest of us see over Norfolk. His name isn’t Billy. That’s the name he took when he arrived.

Having had enough, I wander back to the dock: the outboard engines retired to rust, the fishing boats aggressively sprayed down with hoses, the filleting table stained with blood, the basket of fish guts promised to a speechless old Saudi across Norfolk for his garden. This is where I belong. I spot a huge cooler that has not been opened, but the drain plug has been removed, and water trickles out, a little bloody. I throw open the lid. A thirty-inch striped bass lies entombed in ice, its bluish body so fresh and firm that I half expect it to jerk to life. I can tell it’s a hen, illegal, perfect except for a wound on her jaw where it was pierced by Uncle Gerard’s bucktail.

“He doesn’t put anything back,” says Two Bathroom, appearing behind me. “That’s Gerard’s problem.”

He and my grandfather have come down to clean the bass.

“You never know about him,” says my grandfather, who carries a fillet knife and a big steel bowl. He is still angry about the land deal. I can tell by the way he picks up the bass and flops her on the cutting board. Two Bathroom holds the fish’s head while my grandfather goes to work, his meaty forearms flexing as he cuts into the flesh. Two Bathroom cradles two bright-yellow loaves of roe from inside and places them in the bowl. The brothers strip the meat from the hen’s length. After they’ve left and are safely back up with the others, I pull the remains of the enormous fish from the offal bin and throw them back into the canal. I sit with my legs dangling over the brackish water. The tide has come in.

I hear a basketball bouncing on the dusty driveway court, which Gerard has lit with floodlights. The men have backed their cars out so the kids can shoot hoops. My cousins, all girls, have been ravished by early puberty and are a foot taller than my brother. I hear the basketball thud against the backboard and my brother say, “Fuck,” when one of my cousins fouls him. It’s just me and the blue heron down by the water, the way I like it. The bird stabs at minnows.

“Boy, if you’re going to fish, make sure you mean it,” says Two Bathroom. He’s come back for some reason. He doesn’t even know my name. Maybe he thinks he’ll give me a lecture about the value of hard work. Two Bathroom is a rich man who refuses to buy new shoes. He thinks one day someone will sweep in and take it all away. It can all be swept away. Especially the Cadillac. I catch a glimpse of Uncle Billy on his ten-speed, heading out into the night with no shirt.

I wonder if Two Bathroom intends to tell me about rubbers and venereal disease, or about migration and the Old World. I just want to be alone with the great bird and the tide. But the old man stands there, refusing to leave, his breath heavy. He tells me it’s a shame I’m going to spend my life fishing. He says the whole family is cursed that way: fools with fish on their minds.

“They’re just immigrants,” he says. “We are all just immigrants.”

“Not me,” I say, startling even myself.

Two Bathroom totters for a moment and appears to think about this. Is it true that by virtue of luck and pink skin I have escaped what he dreads most? I can see the remains of the striped bass in the water below. The crabs are already on it, and I start to point this out to Two Bathroom, but he has gone up the landing to the party, never to speak to me again.