From ten Saturday morning — when your father picks you up at the house you don’t want to live in, your mother’s boyfriend’s house — to eight Sunday night, when your mother retrieves you from the house you never wanted to leave but are now allowed to visit only twice a month, you have thirty-four hours for your father to prove to you that he’s not the man your mother says he is: the man she left, the man she didn’t want coming into daily contact with her or her child anymore, the man who tells you things about your mother you’d rather not know, the man who now cries in front of you when talking about having had his family “stolen” from him, the man who places a hand on your shoulder, stares above your head, and says that you have to tell your mother that she was all wrong about him; thirty-four hours to lie on your back on your old bedroom floor, moving your outstretched arms and legs up and down as if making a snow angel while saying, Mine, mine, mine. Thirty-four hours to wander around the neighborhood, tracking down your friends Jason, Curtis, and Johnny and reminding them that, although they haven’t seen you in two weeks, you’re still the best friend they’ll ever have, which you prove to them by laughing the loudest at the stupid jokes they tell; by slowing down and letting them tackle you just before the goal line in your backyard football game; by sharing with them the beers you’ve pilfered from your father’s fridge; by passing out your father’s Playboys in your room and locking the door and promising them that you’ll talk your father into subscribing to Penthouse next or maybe even Juggs or Fling; by not complaining about the cheap shots they take at your stomach and face when you have wrestling matches; by squeezing with them into the back seat of your father’s car so he can drive you to Mario’s for all the pizza you can eat, all the soda you can drink, and all the quarters you can pump into the pinball machine; by convincing your friends’ mothers that your father is not going to the bars tonight (you don’t exactly look them in the eye, but you’re convincing nonetheless), so it’s all right for their sons to sleep over at your house, all four of you smushed into your queen-size bed, smoking the cigars your father had forgotten about in the bottom of his desk drawer and talking about the girls in the neighborhood who have grown tits and the chances of your ever getting to feel those tits and what you’re going to do to the girls’ houses on Halloween if they don’t let you feel their tits. And when silence sets in among the four of you so completely that you can hear your own heart beating, you panic over the time you’re wasting, over the thought that this precious moment is getting away and will never return, because you now get so few moments like these. So you promise your friends they’ll have even more fun on future nights when they sleep over: more beer and possibly peach schnapps; porno movies; a visit from hot Debbie Jones, who lives on Juniper Street; shooting your father’s pistols; anything, anything that will have them looking forward to seeing you again, that will make it so much harder for the memory of you to slip from their minds during the time you are away.

Independent, Reader-Supported Publishing

©

Fiction

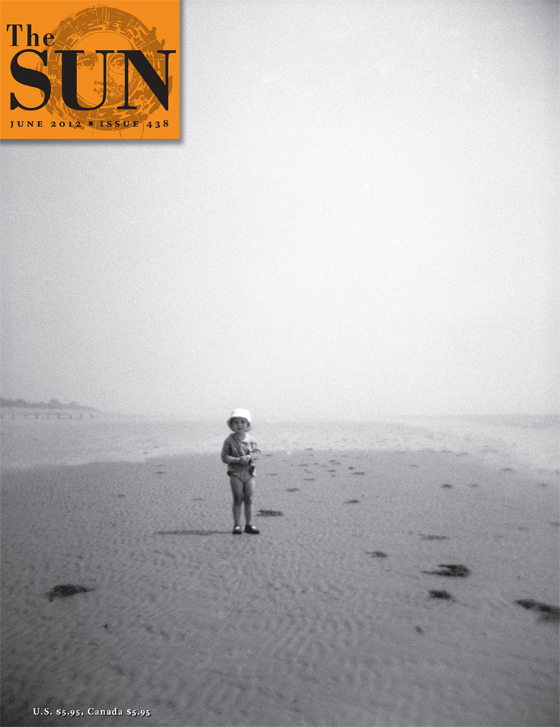

On The Verge Of Extinction

Correspondence

Kelly DeLong’s short story “On the Verge of Extinction” [June 2012] is a powerful account of the agony children go through each day after a divorce. Many hide their suffering and shame from their friends, fight a constant internal battle, suffer through accusations they don’t want to hear, and move from one place to another, always fearing they will upset one parent or the other.

The scene that really grabbed my heart was when the young boy, having arrived for a weekend at the house he’d grown up in, lies on his bedroom floor and moves his outstretched arms and legs, all the while repeating, “Mine, mine.”

Free Trial Issue

Are you ready for a closer look at The Sun?

Request a free trial, and we’ll mail you a print copy of this month’s issue. Plus you’ll get full online access — including 50 years of archives. Request A Free Issue

Request a free trial, and we’ll mail you a print copy of this month’s issue. Plus you’ll get full online access — including 50 years of archives. Request A Free Issue

close