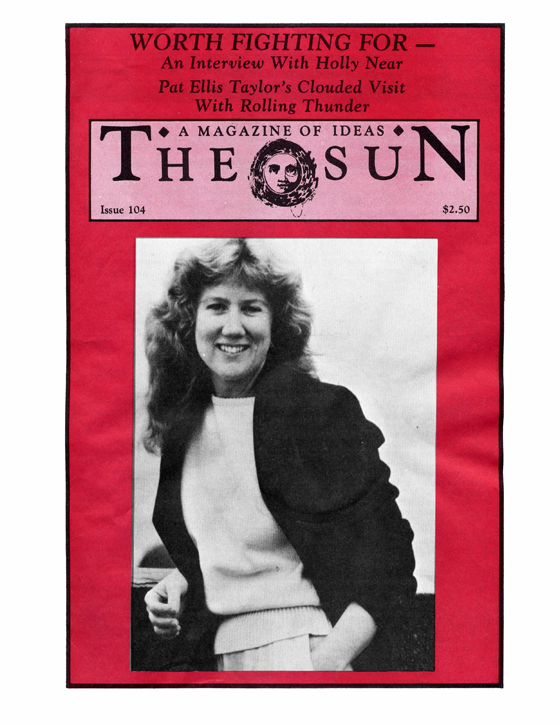

“You are not apolitical when you’re an artist,” Holly Near asserted in a recent interview. “Artists have a certain political power. . . . You’re an affecter.” Few songwriters seem to really understand the implications of their words, and fewer still wield them as consciously and gracefully as Holly Near. Her name has become virtually synonymous with “women’s music” — her concerts are part political rally, part feminist meeting, and part pure entertainment. Unabashedly feminist, lesbian, anti-military and radical, Near is also unabashedly human. When she rears back her head of blond hair and sings songs in polished soprano, you can tell she’s felt each word. Her songs are passionate and revealing — whether it be passion about a new lover, or the B-1 bomber, the sincerity shines through. In her eleven-year, eight-album career, Near has shifted style and emphasis many times. She consistently defies her own labels. Through it all she’s found a rare, fine harmony between politics and music, righteous anger and warm good humor.

Holly Near was brought up in the small farming town of Ukiah, California. Her parents were both political activists who became farmers during the paranoia of the McCarthy era, and actively supported her artistic ambitions. She began singing in public at age seven. Early on she was moved by the emotional effect music had on her. “I used to put on Judy Garland albums and stand in front of a mirror and lip-sync and make myself cry,” she remembers. “It was astounding to me how a piece of music could open me up and make me feel so vulnerable.” In one of her song books is Near’s high school picture — an aspiring school beauty queen and actress, all straight lace and pink ribbons, she seemed the perfect, most-likely-to-succeed graduate. When school ended she left home for star-studded Los Angeles.

She studied theatre at the University of California in Los Angeles, and soon landed small parts in a number of television shows and films (including “All in the Family,” “Mod Squad,” “The Partridge Family” and “Slaughter-house Five”). In 1970 she sang in Broadway’s “Hair.” Her career was booming. It was also in this period that Near’s radical political interests were piqued. On the night of the Kent State shootings, the cast members stopped the performance during the singing of “Let the Sun Shine In.” “There is no sunshine in our lives with these things going on,” they said, and the startled audience joined them in a moment of silence. Near says that night demonstrated for her how artists could use their influence skillfully. She began to feel uncomfortable in show business, and, passing up some movie options, joined a “Free the Army” troupe headed by Jane Fonda and Donald Sutherland to entertain American G.I.s in the Philippines, Okinawa and Japan.

With that tour, Near’s change of direction was complete. “It showed me that incredible things were going on in the world, and they weren’t being made into TV shows,” she says. “I was in the Philippines, meeting women who had been farm girls just like me, and now they were prostitutes because the military had come in and taken all that beautiful farmland and made a military base out of it, and they had no place to work. I couldn’t not pay attention to that.” Now she had found a focus for her art — fighting the war in Vietnam. Returning to Los Angeles, she joined with song-writing partner and accompanist Jeff Langley to write and produce an album of anti-war songs called “Hang in There,” financed with money she had earned in her television and movie days. Major record labels showed no interest in the project, so Near set up her own distributing company — Redwood Records — at first operated entirely by her parents, who filled mail orders from their home. Near and Langley did a tour of coffee houses and small concert halls, carrying cartons of records with them to sell at the shows. The record sold an astonishing 40,000 copies. While still striving for a major record contract during the next few years, Near refused to blunt the blatant political message of her music, and continued putting out popular albums on an expanded Redwood Records. To date her records have sold nearly half a million copies.

Officially coming out as a lesbian with her 1976 album, “You Can Know All I Am,” Near began to work solely with women musicians and producers. In the last few years she’s loosened up on that issue and is again playing with men. In many ways, Near feels that she’s allowing herself more tenderness or softness than she once did. Her songs are growing gentler, with more intimate love songs (still mostly lesbian) and less overtly angry political overtones. I felt that when we met. Though I arrived feeling defensive, my male armor at the ready, her warmth and good humor let me lay it quickly aside. In the concert immediately after our short talk, her manner was buoyant and self-assured; she is a righteous yet vulnerable dreamer, whose dreams, I found, touched a common chord.

At 35, Near’s music is gradually moving toward mainstream acceptance. “My goal right now,” she says, “is to reach a large and diverse audience — and still to maintain who I am.” With her records gradually gaining more air play, and recent appearances on the “Today Show,” “Sesame Street” and even in People magazine, that goal doesn’t seem too far off. Still, Near doesn’t make too big a deal of her changes over the years. “I try to follow my heart,” she says, “to keep curious, to keep adventuresome — and not be afraid to fall on my face.”

Holly Near’s Cultural Work, Inc. is a non-profit organization that supports her educational, political, and non-commercial projects and publishes a quarterly newsletter. Donations can be sent to 478 W. MacArthur Boulevard, Oakland, California 94609. Her new record, Watch Out is now available.

— Howard Jay Rubin

SUN: Let’s start by talking about sexism. Most of us are familiar with the more overt forms of sexism, but it has more subtle aspects, in our thoughts and interactions.

NEAR: Attitudes are usually taught, and then reinforced by the system that we live in. There is external sexism — someone expressing sexist attitudes toward a woman — and then there’s a woman’s own internalized oppression, because she too has been brought up in a system that teaches these attitudes about women. I may discover in myself an acceptance of certain things and then catch myself accepting them and say, “Wait a minute.” It works both ways; that’s why it’s so hard to combat it. If women were completely free of those attitudes about themselves, they would be more outraged when confronted with them. But we’re taught to buy into them. So when someone says something to us, or behaves in a certain way that is sexist, there’s an element of doubt that goes through women’s minds, asking, “Is that how it’s supposed to be?” And then, the question is followed by a fear that if I challenge that attitude and call somebody on it, then not only do I experience the sexism, but I also experience their defensiveness and denial that it happened. It’s very difficult.

It’s the same with racism. It’s the same with ageism. We’re taught these attitudes and then the systems we live in, the institutions we work in, reinforce those attitudes. The culture we build reinforces them. There are very few places you can go to find reinforcement for a change in attitude. You see, I don’t believe there is absolute, total freedom. I believe there are choices. As a blatant example, the community has to decide, “Do we support the rapist or the victim?” They can’t both be free. And I want to live in a system that supports the victim’s right not to be raped. I want to live in a community where everybody absolutely believes that to be true. When a woman is raped in the middle of the night, walking home from work, the first question must not be, “What was she doing walking home alone at night?” The moment that question is asked the woman’s internalized oppression finds a voice and she wonders, “Maybe I shouldn’t have been out walking at night.”

You have to remember what lovemaking is like. You have to remember what a society with no starvation is like. You have to remember what it’s like to have people singing freely in the streets. In order to want to fight and die for those ideas you have to remember them.

SUN: You mentioned the tendency to deny sexism. For myself, I could easily say that I’m not sexist — but it’s not true. I’m sure there are ways that I am. Where would you point a person looking at those attitudes in himself?

NEAR: I think the first thing is to acknowledge that the best of us — the people who have worked the hardest — still grew up in a system that perpetuates these ideas, and still live in that system. To deny that is the first error. For a white person to deny having any racist attitudes is liberalism. If I say to a black person that I don’t have any racist attitudes, right off the bat they’re not going to believe me. Already we have a relationship of mistrust.

SUN: So one has to remember that changing such attitudes is a constant process. It’s not some kind of born-again non-sexism or non-racism.

NEAR: It is a life-long thing — for women in terms of their internalized oppression, and for men in terms of their external attitudes. If we acknowledge this, we can then find moment-to-moment joy when we catch ourselves, rather than feeling only guilt. When you catch yourself doing something you can stop and say, “God! I’m sorry. I just caught myself at that,” and not feel, “Oh God, I just went and did this stupid thing.” You can work to be a walking example of a man who is challenging sexism — not a walking example of a man who has completely eliminated it from his person, but a man who finds joy in discovering that every moment he has the ability to catch himself and change. For white people, for men, it requires a lot of listening. It’s the same for middle-class people; we believe that our way of life — the white middle-class way of life — is the best way to do things.

SUN: Which is at very least an unconscious assumption.

NEAR: It’s very hard to let go and see that maybe we have concluded that this is the most efficient way to do something, and perhaps there are times when efficiency isn’t really the goal. Then we can be excited about each other’s differences, rather than fearing them.

SUN: In even the most intimate relationships it’s hard to keep from objectifying the other person and trying to fit them neatly into your own way of thinking. For example, what we call making love is often much more pornographic than loving.

NEAR: It’s an interesting thought — acknowledging that the human animal has passion and seeing that passion turn into violence applied to another. Where is the passionate part of human experience that doesn’t have to be violent, or passive? There can be assertiveness, and there can be power dynamics, and there can be adventurism in lovemaking, but there is a line to be drawn. We want to allow an expression of sexual creativity and passion without perpetuating in each other the acceptance of those things that are racist or sexist or pornographic. I think those are very difficult lines that partners have to work out with each other, avoiding situations where you’re demanding that your partner be the victim of your passion, as opposed to participating with you in a creative passion.

SUN: How do you deal with catching yourself in a kind of reverse sexism, objectifying men?

NEAR: I don’t believe in the concept of reverse sexism or reverse racism, until such time that we have a system that supports and validates changing the dominant culture. For me, when I react negatively toward a man, it’s usually a conclusion of a long history of experiences.

SUN: A conclusion that all men tend to be a certain way?

NEAR: Yes. If I make a generality about men or say something like, “God, I wish they’d all get out of here,” it usually comes out of my accumulated experience. It is a defense mechanism, a way of defending myself against institutionalized sexism. I don’t think that’s reverse sexism, because if I lived in a world where I wasn’t constantly bombarded with billboards of women in bikinis selling toothpaste, and if I didn’t sometimes doubt the sincerity of men’s participation in the world, then I don’t think it would ever occur to me to make general, critical comments about men. It’s not in my nature to generalize a whole group of people and then dismiss them.

SUN: Granting that any comment you’d make might generally be true, isn’t it hard to do that and not blind yourself to the individual right in front of you?

NEAR: Since I’m a woman I can’t speak from a man’s point of view, but I can speak from a white person’s point of view. When I’m with someone who is black and they let their rage come out toward white people, I really understand that. I don’t take it personally. I can be white and not like white racism either. They suffer from that more than I do by virtue of their color. Sometimes it just gets to be too much and they explode with what some people might call reverse racism. But I don’t hear it that way. I think, “If I were you I’d be pissed off, too.”

SUN: Okay then, my next question is, how do you personally walk the line between being a feminist and being a human being? How do you keep from seeing men symbolically rather than compassionately, as people?

NEAR: I don’t know. It feels easy. I’m sitting here having a conversation with you, and I’m not thinking, “Oh, I’m having a conversation with a man.” In that sense it’s easy. But if all of a sudden you started acting out a lot of sexist behavior, then you’d quickly become a man in my eyes, and I’d either try to block it out so I wouldn’t receive it, or I’d try to educate you, to struggle with you. I believe that, exhausting as it is, women have to be constantly re-educating, and challenging those ideas, as do men who have already been convinced that sexism is a bad thing. I really like it when I see men doing education work around sexism.

I want to live in a world where there’s equality. I work in a lot of coalitions because I think it’s one way to work toward that goal. I remember a white woman I knew who was doing a lot of soul-searching, wondering how she got her racist attitudes, thinking back to her early childhood. She had been in a school full of white kids at a time of a liberal momentum toward integration. Her particular school hired a black teacher. At that time it was a very big deal, although now we look back and see that it wasn’t enough. It was all that white people, struggling with racism, knew how to do. Here was a black teacher with a class of white children. They were asked to draw a picture of their classroom. Now in those days, and even today, the children of liberal parents were brought up not to notice that a person was black. It was before black power, and the children were brought up to see that we’re all the same, we’re all one — a big UNICEF card of one big happy family. They weren’t supposed to notice that people are black, thus denying the richness of blackness. One child begins to draw her picture. She colors in all the students and then gets to the teacher. Here the child is posed with a major problem. How should she color the teacher? She knows the teacher is black, but she’s been taught not to notice. Unable to cope with that problem, she erases the teacher out of the picture. I think that this is what liberals have done. Politically, we support integration, but in our own lives — out of fear of confronting our own racism — we live in segregated worlds. In order to combat these fears we have to be willing to confront them. We have to be willing to work in coalition. We have to get used to each other’s differences. We have to learn to co-exist, especially within our political organizations. Separatism, in relation to that idea, is a very important process. I feel that when there are people who have been very deeply hurt by oppression over the centuries, often they need to separate themselves from the dominant, oppressive culture and try to get their feet on the ground and figure out who they are and what they’re doing. Indians have done that. Black people have done it. Working class people have done it. Lesbians have done it.

For centuries, the smart people who have tried to change things have first gotten together. They have not tried to face those problems alone.

SUN: You’ve made the comment before that while separatism is important, you have to go out and make friends with the people with whom you’re sharing the world.

NEAR: I have to, because that’s my way of being in the world. Sometimes I have to separate myself even from my friends, to go in my room and close the door for a while and say, “What am I doing?” And then I go out into the world and live and work with people, because that’s the kind of work I want to do. If there are people in the world who can’t function in coalition, or just don’t want to, and see their task as being part of a separatist community, I don’t mind them being there. I believe that we have to make room for people to live according to their needs. Somebody might live in a separatist community all of their lives. Others might see it as just part of their journey and later return to coalition work. Others might never separate themselves. But to deny the needs of a separatist doesn’t get us anywhere.

SUN: One reason I wanted to do this interview is because I’ve noticed that, without having heard much “women’s music,” something in its image, or in me, was alienating, prejudicing me against it. I assume that part of your work is crossing that bridge to reach people. How do you react to that?

NEAR: I think it’s interesting, because when I first heard about women’s music — and it had been going on for a good seven years before I participated in it — I had a similar kind of prejudice. I had the same feeling about the early efforts of the women’s movement. What are these women doing? Why are they out making all this noise and being so obnoxious? I was still influenced by institutionalized sexism instead of getting excited that finally women were standing up for themselves. They were saying, “There’s no reason when I walk down the street in front of construction workers that I have to cross to the other side in order not to be harassed. I won’t do that anymore. They have to quit harassing me.” I didn’t think of that when I was growing up. I crossed the street to avoid the harassment, figuring that they had a right to harass me and that it was my responsibility to stay out of their way. Bless all of those women who finally came to the conclusion that it’s not right, that we had a right to walk down the street and the construction workers were the ones who had to change. They had to be very verbal and assertive about that opinion even to reach people like me, and I myself was a victim of those comments. When I first heard about women’s music, I wondered why they were having to separate it. Why were women doing this? It became clear to me that it was necessary as a way to build a movement that gives us the security and support to dig down into those deepest hurts as well as those deepest creative places, and come up with new ideas about how to confront our problems. It’s very hard to do that alone out in the middle of a world where you grew up hearing that you can’t, you shouldn’t, you mustn’t. For centuries, the smart people who have tried to change things have first gotten together. They have not tried to face those problems alone.

SUN: Would you say, then, that you’re more interested in offering that kind of support than in trying to change people’s views?

NEAR: The first thing I had to do when I started understanding sexism was to deal with my own rage and hurt. Looking back over my life I thought, “Damn. I played the acoustic guitar in high school, and when all the boys picked up electric guitars and formed rock bands, I became the girl singer.” I had to deal with the fury I felt. I played the acoustic guitar just as well as any of them, but who would have ever thought that a girl should plug in and play the electric guitar? Understanding this, I had to first educate myself; I had to get strong in my own mind and body. Only then would I have the leeway to go out and become a teacher.

When I do a concert, one purpose is to entertain. That’s what I do; I’m an entertainer. Another is to educate people, to present new ideas. The ideas are not set, because I’m in a constant state of change. What I put out in a concert tonight is only what I know today. It will be different in a few years. I invite the audience to look at my information and add to it. And they do. I get letters from people who say they were moved by a concert, and now they’ve learned something else which they give to me. It’s not that Holly Near has got all the answers and everybody comes and learns. I want to challenge people to change, not be afraid to grow and learn, and then turn around and teach what they know. Another effect of a concert is refueling. People who already know the things that I’m singing about come to be refueled, to be encouraged to keep going under duress, and to be encouraged to celebrate their victories.

SUN: It seems that so often the work we take on, even if it’s to educate others, is that which we ourselves have the most to learn from. Looking back over your career, what stands out as having been an important lesson?

NEAR: Every time I think I’m set in my ways something comes along and pushes me off my toadstool. It seems like my life is not set up to let me sit still. And that’s good. I’ll have to rest in another lifetime. Every time there’s a group of people, or a nation, or an idea that I have neglected, something comes along to place it in front of me saying, “You have to learn to love. You have neglected this part of yourself, or of society, or of the world.” In a way they’re the same, because if you hurt somebody in the world, you’re really hurting yourself.

I just got back from Nicaragua. I hadn’t known much at all about this country that the United States has been involved with for many years. The Marines were in Nicaragua as long ago as the Thirties. How can you live in a country and not know about a place where your Marines have been for that long? My money and my soul have been paying the price for what’s been going on. I have been drinking their coffee, eating their bananas, without knowing how many people have died under the brutality of a dictatorship that allowed the coffee and bananas to be on my pleasant little dinner table. Then all of a sudden I hear that there is a revolution and people around me are excited and astounded that this tiny country could defeat a tyrant like Somoza, and a country as big as the United States. It became my time to realize that I’ve got to know who these people are.

SUN: How do you reconcile your political views and actions with your spiritual views?

NEAR: Where do you see the contradiction?

SUN: I don’t see a contradiction. I’m asking how you reconcile them in your life.

NEAR: They feel as one to me. I think if my heart was detached from my politics I wouldn’t be able to do political work. My politics don’t ever contradict my heart, even around the subject of defense. When I was in Nicaragua I sang for soldiers, some of whom were part of the volunteer community militia — men and women who are trained in self-defense, using whatever they have. If all they have is kitchen knives that’s what they use. If they have guns then they learn to use guns. These are not people who want to use guns. They are not trained killers. They are people who’d rather be in school, building childcare centers, going to the beach with their families. They are people like us — artists, farmers — but they remember what it was like being under Somoza. They remember seeing their wives and daughters beaten and raped. They remember seeing their sons drafted into the military and forced into service. They remember seeing homes burned and cities bombed. They remember a town where a lot of young people rebelled, rose up against the brutality and were captured, brought into the center of town and hung as examples. Every family of the working people in Nicaragua can tell you a story of someone in their family who was brutalized by Somoza, and someone who died in the war defending themselves from him. Though liberated from that regime, it’s fresh in their memories. If what that means is that when the Contras are attacking they have to go to the border and fight back, they will. I sing for these soldiers. Ten or twelve years ago, I started my international work by singing for soldiers in the United States military who believed that the war in Vietnam was bad, and were organizing from within the military to stop G.I.’s from going to Vietnam to kill Vietnamese people. I sang for those soldiers, encouraging them not to go to war, supporting their resistance. In Nicaragua it was the first time I sang for soldiers knowing that my music was encouraging them to fight and defend themselves. It was a very different experience. And you could ask, “Doesn’t that challenge your belief in being a pacifist? Doesn’t that challenge your belief about killing?” It didn’t. I absolutely knew that if I lived in Nicaragua, and I knew of these tyrants who believe in torture and terrorism and an elite few brutalizing an entire population in order to get rich, and I knew that they were coming to terrorize me, I would go out and fight. And knowing that about myself, I felt I needed to support the courage of those people who are fighting, especially since the country I live in is supporting the attack. The C.I.A. is invading them constantly with our tax money that should be going to social services, our schools, our music, and is instead being used to support these right wing fascists whom I wouldn’t accept living in my backyard. It became very easy to sing for these people. There was no spiritual contradiction whatsoever for me. I came back to the United States with an incredible amount of energy, wanting to support those people who do have a spiritual place in our lives, not out of guilt but out of enthusiasm for humankind, to quit avoiding the essence of the problem — that we have a system in this country that is brutalizing people all over the world.

SUN: One last question. While I’m not feeling this in you, one thing I often find in political movements is a decided lack of humor. What makes you laugh at your political self, and your co-workers? What do you find funny about it all?

NEAR: I laugh at how hard we try. We try so hard and we make such mundane mistakes, getting so close to something that we can’t see it anymore. Often I have to laugh at myself. As a writer I’ve been trying to clean up my language. Poets for years have been saying things like, “I once was blind, but now I see,” which simply perpetuates the idea that blindness is ignorance and being able to see is visionary. If you grow up blind and keep hearing that, it’s not a great image. And it’s just not true. In the same way I am aware of the image that maleness is to succeed and femaleness is to submit. When I find these lines in my writing, instead of feeling guilty or beating myself up over it, I just laugh, because they’re such obvious mistakes. I wonder how someone who grew up with access to so much information can make such a silly mistake (laughs). Sometimes when it all gets too big for me, I climb up outside of the earth and look down and see all these little creatures running around frantically trying to solve their problems. If we’d all just stop for a minute and look at it! It doesn’t take the edge off it for me; it intensifies the edge. It also allows me to keep remembering joy and happiness, because as we tear down that which is oppressive to us, we have to build up the kind of society that we want to put in its place. The only reason to work hard at resistance work is this image, this knowledge, this wisdom about how the world could be. You have to remember what lovemaking is like. You have to remember what a society with no starvation is like. You have to remember what it’s like to have people singing freely in the streets. In order to want to fight and die for those ideas you have to remember them. My concerts, my music, and my life are filled with that joy and happiness so I can remember what I’m fighting for.