Somebody gives Gus a push from behind, probably one of the Dutton twins, the way they’re giggling and playing slap-ass, and suddenly Gus is out there in the middle of a nest of lights and cables and strangers. Microphones float toward him like giant sweat bees, and then the cameras move in. This woman steps from the pack and takes his arm like she’s steering him toward the center of a dance floor. She’s tall, with a lot of hair, and a dress that flashes points of light whenever she moves, which seems to be all the time, and these high heels a color that brings to mind certain body parts.

“That’s Kathleen Sullivan, I bet,” Ernie says. We’re all jostling around, hoping to stay in the background, except for Sue Ellen, who’s waving at the cameras and trying to show her best side, which she thinks is her left, though truth is Sue Ellen looks the same no matter what direction you’re coming from.

“Maybe the Chinese woman on the other channel,” Myrna says, turning to me. “What’s her name, Tack?” she asks. They call me that because that’s what I do to fix the upholstery in place.

“Chung,” I say. “Connie Chung.”

Then the reporter lays her hand on Gus’s shoulder and turns him toward the cameras, and we all shut up.

“Dan,” she says, “Mr. Gus Kincaid, an employee at the Sweet Cider Furniture Works, is going to give us the background.”

“Who’s Dan?” Ernie whispers.

Gus squints into the camera. He brings a hand up to shield his eyes. “We have here what you could call an incident,” he says. Then Gus looks around and grins, like he’s just delivered the long-lost sequel to the Gettysburg Address.

The lady places her hand on his wrist and lowers his arm. Her fingernails are the same color as her shoes. She allows how public officials are saying we are Terrorist Agents of a Foreign Power, making it sound like a new brand of cola on the market.

Gus blinks, licks his lips. “Terrorists?” he says. He brings his hand up to shield his eyes again and surveys the circle of cameras. “Hell, we all shave just like everybody else, except for Jeeter over there, and he’s a Presbyterian.”

It was no one thing. It was businesses caving in at the knees all across the country, especially in the Carolina Piedmont. It was having our salaries cut twice in the last three years, our health plan whittled down till you were better off taking your chances at home. It was the layoffs, it was the time that union man from over in Raleigh woke up to find somebody had taken an acetylene torch to his little German car, it was the new foreman they brought in last year, Robison, with his pointy-toed shoes, and ties that look like somebody forgot to get the weave tight. It was his running around with a stopwatch and clipboard and banging on the door of the john and searching through our lunch boxes, afraid somebody’s going to smuggle out a 5/8” diamond-tipped drill between two slices of Wonder bread.

It was no one thing. All I know for sure is what’s hanging up there clear for anybody to see. What Kathleen Sullivan and Connie Chung and public officials don’t care to hear about is that the High Point Area Industrial Mixed-Team Bowling Championship comes just once a year, and that Karen Wheeler has soft places in her heart bigger than continents for Gus Kincaid, and that these two things joined up and made all the difference on Tuesday morning in the cutting room at around 10 o’clock, which used to be break time before they got rid of that, too.

It started when Gus was cutting bevels into the support slats on one of the All-Purpose Combination Finished Oak Bureau and Bookcase Sets, one of our biggest sellers. The craftsmanship on it has got to be hairline perfect, because there are a lot of Gomer-types out there who’ll take a hammer to a piece of furniture if all the parts don’t slip in place first thing. The lathe Gus was working on kept seizing up, so Gus had taken apart the turret and was checking all the parts and being generous with the lubricating oil. Robison came marching up with a red pen scratching against the clipboard in his hands. Robison leaned toward Gus and shouted at him, his voice straining over the roar of the buzz saws, to get back to work. Gus leaned back and shouted at Robison that the rotor had locked up on him, and if he kept running it then Robison was going to be out one fifteen-hundred-dollar lathe. Robison shouted that Gus had another think coming if he thought he, Robison, was going to take that off any man, and how besides he’d been noticing that Gus was slowing up a little and maybe he was getting afraid of an honest day’s work in his old age.

The whole time Robison was scribbling on the clipboard like he was taking down a dying man’s will. When Robison said this last, Gus threw down the oil can and stalked over to the main power switch that supplies the juice to every tool in the room, a safety feature that state regulations say you got to have in case somebody gets a head stuck in a machine that don’t want to give it back. Gus reached up and hit the switch, and all at once it was birds singing outside and the sound of a plane passing overhead and the cackle of one of the Dutton twins, who’d just goosed the other one over in the sawdust pit.

“What?” Gus said, his hand still on the switch.

Robison came running over, his pointy-toed shoes making this little pitty-patter sound, and he was all red in the face and shouting about how he was going to dock Gus half a day’s pay for Unwarranted and Nonauthorized cessation of operations. Gus just stood there for a second with this gray look on his face, his eyelids drooping low like they sometimes get when he’s mad or drunk or both, till you practically have to get down on all fours to see the white part of his eyeballs.

It was real quiet, everybody watching and waiting, the only sound being Robison going at that clipboard. This was when Gus took off his SCHAEFER BEER hat and ran his hand over his head twice, slowly, and said, “Who stuck a horse hair up your ass?”

Then Robison went crazy, screaming stuff about insubordination, and how dare Gus, and before you knew it Robison had canned Gus’s ass and was pointing the way toward the door.

Gus’s jaw fell open on this one, and he went even grayer, and you could tell he was working on whether to lay out Robison right there, when all at once everything seemed to go out of him like something leaking. Gus put his hat back on and turned around and started walking in the direction Robison was pointing, his feet making these sounds like that part of a movie where it’s all dark and quiet, right before the guy jumps out with a meat cleaver in his hands.

We all stood there watching Gus mope his way toward the door, while Robison hung back with his head bobbing and weaving like a crucial hinge had just popped its housing.

We all felt bad: bad for Gus, because now there was nothing left for him but to go back to his mobile home and drink himself stupid; and bad for ourselves, because the Sweet Cider Furniture Works had won the High Point Area Industrial Mixed-Team Bowling Championship three years running, even though some of the teams represented big concerns, like the eight-hundred-employee tractor plant over east of Greensboro. The reason we kept winning, and always got the group photo on the front page as far away as the Charlotte paper, was because of Gus. Gus can pick up a spare almost guaranteed every frame, hitting the ten-seven split when he has to, easy as plucking ripe persimmons. Gus is not what you’d call a big striker; he stretches those X’s out on the scoring sheet as if he has only so many to his name and aims to conserve them. But the strikes are always there when the need is on. Always. Watching Gus bowl, you suddenly find yourself wondering about the size of the universe and the beginning of time and whether there is life in other galaxies.

But to play in the High Point Area Industrial Mixed-Team Bowling Championship, you have to be a full-time, clock-punching employee, and Gus was about forty-five minutes away from being full-time stinking of sour mash.

This is the part where Karen Wheeler jumped in and turned the world around, whether because Karen Wheeler is one fine bowler herself and enjoys as much as anybody kicking the butts of the folks over in Greensboro, or whether, as I’ve said, her heart has spots soft for Gus, I don’t know.

When Gus was maybe halfway to the door, and the sadness of it was already filling up the cutting room like things gone sour, Karen, who’d been working the sander on a piece of mahogany that forms part of our Trundle Bed Ensemble, picked up a half-finished chair leg and marched over to Robison. What happened next is a matter of some debate, as events had broken into a full gallop by this point, but I know for sure Karen Wheeler never actually hit Robison with the chair leg. I mean, no contact ever came up between the piece of timber in her hands and, say, Robison’s head. She merely leaned toward him and said, with that chair leg waving between them, that if Robison did not take himself through the door and out the cutting room, he was going to have to give some serious thought to reconfiguring his toilet seat back home.

Right here was where one of the Dutton twins started shouting, and then Sue Ellen joined in, and Jeeter started tapping the lid of a can of varnish like it was a snare, and pretty soon everybody was shouting things like, “Go on, Robison, git,” and, “Take your stopwatch with you, why don’t you,” and, “That was pretty good the part about the toilet seat.”

Robison’s face turned about three shades of red, ending with plum. With his shoes pointing the way, he carried himself in a wide arc around Gus and out the door. Gus stood and watched like he’d just been fingered in a police lineup.

“Tack,” Karen said, her voice sounding like somebody had her in a choke hold, “would you bolt the door, please?” I went on over and slid the deadbolt in place. It sounded like a rifle coughing up a shell. Things got real quiet, and we all looked at Karen Wheeler with these faces like you’d use in one of those scenes you always read about, but never actually see firsthand — something along the lines of a ninety-year-old grandmother with a walker who witnesses a semi rolling over and pinning a four-year-old, at which point this grandmother runs three-quarters of a mile and manages to single-handedly right the semi and free the four-year-old, who it turns out was not really hurt but only trapped and a little scared. That was the kind of look we all gave Karen Wheeler at a little after 10 on Tuesday morning.

We all must’ve stood in place for about twenty minutes, waiting, I guess, for Robison to return with Mr. Vandergill, the owner, who we rarely see in person, though he is all the time in the newspaper cutting a ribbon somewhere or receiving an award or dining with the Governor. When Vandergill didn’t show, things kind of loosened up.

Everybody started talking to everybody else, like somebody had given some kind of signal. Julio said how we sure probably dealt ourselves out of a Christmas bonus again this year, and Sue Ellen said that she didn’t care, as long as she got home in time to do her hair before the tournament. Gus turned and said something to Karen, and then Karen was nodding a kind of tight nod when her face crumbled and folded in on itself, and she leaned into Gus’s shoulder and sobbed. Gus stood there for a while and let her wet his shirt, until he got sense enough to bring an arm around her.

After a while, there didn’t seem anything else to do but get to work, and that’s what we did, worked a regular day, taking our lunch break like always. At one point, there was this banging on the door, and we all looked up to see Vandergill red in the face and shouting, and Robison dancing around behind him. Frank Durban, who’s a small man with thick glasses, was doing some detail work with an electric jigsaw on the Classic Teakwood Coffee Table, a piece favored by the golfing and debutante set. He was nearest the door, so he headed toward it with the idea of letting them in, but when Vandergill and Robison saw that jigsaw in his hand, alive and chewing at great bits of space, they both stopped their jabbering and turned right around and tore back down the hallway.

Around 3 that afternoon, Reverend Perry pulled up to the loading dock with the church van. He jumped out and started making noises about the fact that we were supposed to have had the new altar, cut from treated walnut, delivered that morning, in plenty of time for Prayer Meeting. Jeeter and I went on over and loaded the altar in the van, and when we finished, the Reverend thrust a wad of money at Jeeter.

“What’s this?” Jeeter said, staring at the fist of green like it was a hornet’s nest.

“It’s the payment,” the Reverend said, rattling the bills. “Straight from the collection plate.”

“Take it on around to the front office,” Jeeter said, “like always.”

“Nobody’s there. I checked already.”

So Jeeter shrugged and took the money and counted it, then he made Karen Wheeler count it. We were all standing around trying to decide what to do when a truck pulled up with a load of fresh-cut cedar. When we unloaded that, Jeeter paid the driver in cash, counting out the bills for everybody to see. We let Ernie sign the bill of lading.

It wasn’t until it was getting near quitting time that we heard these noises and looked out the window and saw Jake Dooley, who’s the county sheriff and holds the passing record over at the high school. He was standing there with a couple of deputies, keeping his distance like there was maybe some kind of contagion on the loose. We all moved to the windows and listened to Jake hollering at us through his bullhorn, but it kept cutting in and out, because Jake’s too cheap to run over to the Radio Shack and shell out for the forty-dollar model. Right then was when the sky seemed to crack open and spill two helicopters. Pretty soon it was vans and cars and people all up and down the lane, and here was where one of the Dutton twins gave the shove to Gus, and before we know it, he’s standing there talking with Kathleen Sullivan or Connie Chung or whoever she is.

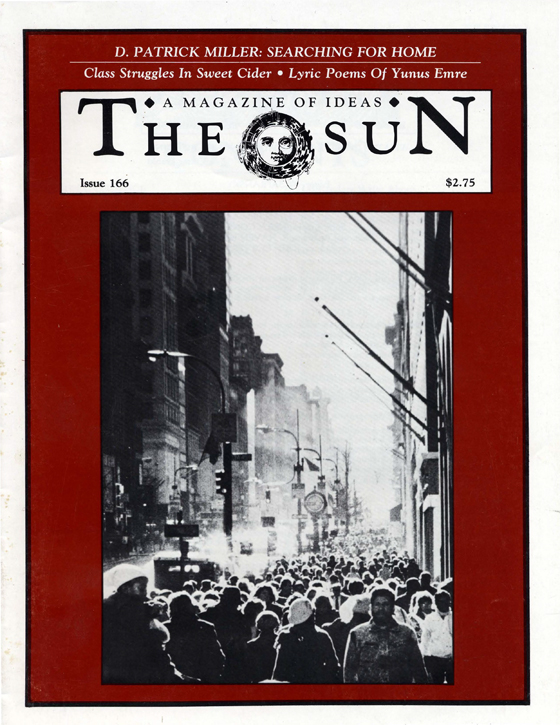

By this time there’s a huge crowd circling the Sweet Cider Furniture Works, including a group of longhairs from the college. The longhairs are chanting things about Angola and Nicaragua and selling newspapers with the ink still wet. Julio talks to one of them, and before long the crowd is passing pizzas from the local Mr. Pizza over the chain-link fence that surrounds the factory. There’s everything from plain with extra cheese to the works with extra anchovies. Soon we’re settling back and eating pizza in the cutting room. One of the Dutton twins decides we should post a lookout at the front gate, and everybody finally says OK, mostly because the Dutton twins look like they really want something to guard. So we go ahead and give one of the Dutton twins a whole pizza, black olive and Canadian bacon, to himself. He parks his butt out near the gate and is happy. By this time we’ve pretty much figured out that we’re not going to make the bowling tournament, and we spend a few minutes wondering out loud who’s going to take home the trophy and get their photos in all the papers all the way over to Charlotte.

Finally, with her mouth full of mushroom and sausage and another piece on its way, Sue Ellen says, “We’re in some kind of trouble.”

We all get kind of quiet at this, working our mouths around the pizza and thinking about it.

“I figure we walk out that door,” Jeeter says, “and Old Man Vandergill is going to fire each and every one of our asses.” There’s a lot of murmuring at this, like a crowd scene right when the call from the Governor comes through over the telegraph, but it’s too late ’cause they already hanged the man.

“So we stick around for a spell,” Myrna says. Myrna and her husband Charley have been having troubles.

This sets everybody to talking again, things like, “Besides, Myer’s Crossing is probably backed up all the way to downtown,” and, “I was hoping to lube the pickup tonight,” and, “I didn’t want to drive my mother-in-law to Durham anyhow,” when Ernie says, “As long as they don’t bring in dogs. As long as it isn’t a bunch of cops running around with these dogs on leashes.”

“Cripes, Ernie, this isn’t Poland,” Karen Wheeler says.

“It’s just that I saw this movie with Paul Newman once, and it was dogs and leg irons.”

“Yeah,” Gus booms suddenly, looking around the room with a face like Hoss used to wear when it seemed like somebody was about to haul off and slug Little Joe. His eyes settle soft as a breeze on Karen Wheeler. “This ain’t Poland somewhere.”

It’s not until morning, after a restless night of sleeping on the sawing tables, that we find the TV in Vandergill’s office. We all crowd in to watch, except for the other Dutton twin, who’s pulling guard duty out at the gate. Bryant Gumbel talks about us, then Jane Pauley, then that person on the other channel nobody knows the name of, because the network never keeps people long enough for their hair to settle. We see Gus on the tube, and everybody cheers, and then we see the factory, how it’s thick with people all around it. Sam Donaldson explains how when word got out, the folks over at the tractor plant in Greensboro shut down the line and settled in, which makes us feel pretty good, on account of we had them figured to win the tournament. Then there’s a clip of a textile mill up in Roanoke with everybody sleeping on these big bales of cotton, and an interview with an auto worker in Detroit. Behind him we can see this couple snoozing in the cab of a half-built Chevy wagon.

The longhairs out in the crowd manage to get a bunch of morning papers to us, and there’s Ernie, right there on the front page of The New York Times, scarfing down a green olive and pepperoni.

By 9 in the morning the telegrams start rolling in from all over, from places like Tokyo and Paris and Knoxville. There’s even one from Albania, which Sue Ellen insists she visited last year, though I think she’s talking about that weekend she went north to see her brother. It reads like one of those instruction booklets that always come with tortilla makers made in Taiwan.

After a while, we all drift over to the tables and get back to work, because everybody’s tired of talking and we figure we’re here. It’s almost lunch time when the Dutton twin who’s been out at the gate comes rushing in, waving his hands like the flood wall at the north end of town just gave it up.

From the window the crowd looks even bigger than it was yesterday, and there’s more TV cameras and reporters and longhairs and cops. Then Jake Dooley steps from the crowd. Jake’s wearing his good uniform, the one with the big brass buckle and the stiff lapels, his Fourth of July Parade Special. He’s finally gone out and bought himself a new bullhorn. His voice comes kind of high and tinny.

“WHAT,” Jake screams, “ARE YOUR DEMANDS?”

We all stand around and chew on this one for some time.

“I wish they’d get a bigger selection in the candy machine,” the other Dutton twin says. “Every day it’s Baby Ruth or Milk Duds, Baby Ruth or Milk Duds.”

“How about maybe we get rid of Robison,” I put in. Everybody nods at this, and that makes me feel pretty good.

“How about a raise?” Julio says.

The heads are really wagging now, and this is when Jeeter holds up his hand until everybody gets quiet. “You heard what’s happening over in Greensboro, and in Roanoke,” he says.

Karen Wheeler scratches her head and says, “I think maybe we ought to tell Jake that we’re just fine in here. I think maybe we ought to tell Jake he can head on home.”

Now there’s a buzzing real loud, though there’s not a saw spinning.

“You work for the man, you play by the man’s rules,” Myrna says softly.

“Until the man cans your ass,” Gus puts in.

“Look,” Frank Durban says, stepping into the middle of the room like a fight referee. “Fact is, you come to work, you do the best you can. You build the best set of table and chairs, or the best bookcase, or the best set of drawers you know how. That’s what we’re here for, is the way I read it.”

Jeeter gets this kind of faraway look in his eyes, and says, “Knew a miner once, wanted nothing more than to put a roof over his family’s head and set food on the table, maybe have a weekend or two out of the year for hunting and fishing, wanted a church to go to and clean sidewalks to walk down, but ended up spending most of his spare time trying to scrub the coal dust out of his hair.”

It’s not till around 5 in the afternoon that we get things settled among ourselves. By this time people are outside selling hot dogs and soda pop, and they’ve brought a clown up from the State Fair over in Raleigh to do some juggling and make the kids laugh. Karen Wheeler and Jeeter walk out to just this side of the chain-link fence, and word spreads through the crowd like something alive. Jake climbs up on the hood of his patrol car.

“You all can go on home now,” Karen Wheeler yells. “We’re doing fine here.”

Jake looks around at this one, you can see him turning things over in his mind real slow, like a horse-drawn plow working a field. “Karen,” he calls after a few minutes, “there’s Mr. Vandergill here, and he wants to get back in his factory.”

“We don’t need Mr. Vandergill, thank you,” Karen calls back. This really sets the crowd to hooting and hollering, and it’s some minutes before Jake can get everybody quieted down.

“This here’s private property,” Jake calls now. “You are trespassing on private property.”

One of the Dutton twins elbows the other. “It’s just like in that game with Greensboro North,” he says. “’Member? Fourth and long and instead of kicking, it’s a quarterback keeper. They buried Jake at his own twenty.”

“My grandfather helped build this factory,” Jeeter calls now. The cords in his neck are standing out like some kind of natural formation on a map.

“That don’t make a difference, Jeeter,” Jake says.

“And my father worked forty years in it —”

“That don’t make a difference,” Jake says again.

“Maybe not. But I’m in here, and you’re out there, and that seems all the difference there is worth talking about.”

Things have to break off here, because Lila Woods from down at the Community Center drives up and wants to look over the tables we’ve been working on for her Saturday night bingo tournaments. Jake tries to take Lila’s arm and lead her away. Lila’s a small, white-haired woman the far side of seventy, and when Jake starts pulling on her, she starts pulling back, and pretty soon it’s Jake all red about the ears and kind of half-dragging her, with Lila screaming in that shrill manner women seem to perfect only after long years of practice. Then the crowd’s booing and all the deputies are standing around looking uncomfortable and all these cameras are whirring and clicking. So Jake lets her go finally, hitches up his pants, and tries to help Lila Woods up. She lets him have the flat of her purse across an ear. Then it’s Lila Woods brushing off her dress, a baggy print pattern that makes her arms look white as milk, and she squares herself and marches right up to the gate, which one of the Dutton twins holds open with a bow, the crowd crazy cheering and the cameras following her and the reporters running and Jake looking sick and miserable in the face.

It’s Thursday afternoon when I open the door to the storage bin. I’m looking for a new place to sleep tonight. The cutting-room floor, littered with cots and sleeping bags donated by the longhairs, is too noisy. The Dutton twins giggle all night long, and Sue Ellen keeps moaning in her sleep.

Karen Wheeler is sitting on a box of wall braces in one corner of the storage bin, smoking a cigarette. “Hey,” I say.

“Hey, Tack,” she grins.

I wander over to her side. We’re both quiet for a while, then I say, “So what’s Jake going to do now?”

“Nothing,” she says after a time. “I expect Jake’s out of the picture.” She grinds out her cigarette and lays her arms across a block of pine. Her arms are pale and thin and pretty.

“You know what’s making them —” and here she nods toward the window, “— eat their livers? The fact that we didn’t go out on some damn picket line while Vandergill and Robison stayed snug and grinning on the inside. They can handle picket lines, and National Labor Relations Boards; but this. . . . They got to do something soon,” Karen Wheeler says now. “Meantime, they’re messing their pants.”

We spend the next couple of days getting up and working as usual. They keep the pizzas coming, and there’s a takeout Chinese place that throws in free egg rolls with every order. Thursday evening the “Sixty Minutes” people show up, and Sue Ellen nags after Diane Sawyer about where’s Andy Rooney anyhow. Ted Koppel arrives on Friday morning, and Ernie spends the rest of the day muttering, “His hair is for a fact that way.” By this time we’ve gotten three new orders, one big one from something called the Bulgarian Consulate for a whole dining room set with a sixty-foot cherry-wood table and twenty-four matching chairs. Frank Durban’s teenage daughter shows up, and so does Julio’s wife, Claudia, so we make room. Myrna’s Charley arrives late one night, looking for her, and everything gets kind of teary-eyed when they come across the cutting-room floor the next morning holding hands.

They try cutting the power, but they screw the thing up and end up blacking out half the valley for five hours one morning.

Late Sunday evening, Ernie’s moving across the cutting-room floor with a cold slice of hamburger and onion when he trips over a sofa back somebody’s left on the floor and delivers the pizza squarely onto Gus’s lap, gooey side down. Gus sails his half-eaten slice of hot pepper and anchovy at Ernie’s head, but Ernie ducks and it hits Sue Ellen smack in the face. Sue Ellen picks up a piece of plain cheese, as Gus scrambles low and Ernie runs hunch-shouldered across the room. Then one of the Dutton twins steps in, and it’s food parts flying through the air and people squealing and Sue Ellen running around like a wound on the loose.

This is when Frank Durban walks into the room and picks up a hammer, slamming it against one of the brass sheets we use to cut the trim. “Hey!” he hollers, his eyes screwed tight. “You think you’d ever catch Vandergill carrying on like this? Or Robison?”

Everybody gets real quiet, kind of ashamed quiet, like your-mother-caught-you-in-a-crowd-of-kids-laughing-at-a-blind-person quiet.

Then Frank giggles like some kind of Phantom of the Factory and reaches over and dumps a whole carton of chow mein, the kind with the thick brown sauce, over Jeeter’s head, and Jeeter tears out after him with a handful of these little packets of duck sauce, when the other Dutton twin comes storming into the cutting room and makes these motions with his hands like he’s kneading bread.

So we all step outside, and the first thing that hits us is the change. The crowds and the hot-dog stands and Diane Sawyer and the microphones and cameras, they’re all gone. The moon’s out low and full, like a ball bearing God forgot. When my eyes adjust, I can see a long row of these helmets, the big kind with the clear sheet of plastic across the face like you always see in those news clips from Korea. It looks like a bunch of fly eyes ranged single file all along the crest. They got batons the size of Louisville Sluggers. Overhead three choppers are whipping around with light screaming from their bellies and giving things that neon beer-sign look.

“Came in from Fort Bragg, I bet,” Julio whispers.

I don’t see Jake’s patrol car. I don’t see Jake.

Jeeter steps my way, reaching for a tool locker. He pauses, looking down at me. His hair’s all full of fried noodles and sticky brown. “Mary,” he says now, “I think maybe we should take in the cinema sometime. I’d like that.” Then he picks up a portable Black and Decker with the 1” cadmium bit. Pretty soon everybody’s grabbing saws and hammers and two-by-fours.

Off a ways some dogs start up, barking crazy, like hounds just before the geese fall. “I knew it,” Ernie breathes.

“Hey, take it easy,” Gus says, licking his lips. He looks around, then lets his gaze rest on Karen. “This ain’t Poland somewhere, remember.”

“No,” Karen Wheeler says, her eyes soft. “It’s not.”