My daddy can eat so much, his plate and more, my leftovers, my sister’s leftovers, meat-brown scrapings greasebound in the pan, chicken bones he sucks, edges of things, the last half of every cake. He’s big and he’s always more than hungry. Half a box of candy. Two pineapple malts and a double chili cheeseburger. He’s hungry and he’s ancient, he leaves no stone unturned, lets no one waste a thing. “Give me that. There’s good food on that plate.” If he were an animal he’d be a wild boar rooting through the house, nosing crumbs from the shag carpet. His huge hands sop up everything. Grease gathers in the grooves of his fingerprints. “Food is good,” he says. “Eating is good.”

I have his shoulders, his solid stance, his strong, yellow teeth, his long fingers and toes. I’m skinny like he used to be and I love food too. “I could eat you up alive,” he says to me and my sister. He’s the giant who could crack the bones of thieves; he’s the god of the Formica dinner table. I imagine Julie and me roasted and skewered, green apples stuffed in our mouths. He wipes his hands on his Levi’s and digs in, enjoys the fleshy parts and chewy muscles, then crams our toes into his mouth, crunches our finger joints, and sucks the marrow as if calling back the blood that is half his.

My head on Daddy’s chest, my hand in his armpit beneath his sweat shirt — he’s snuggling me to sleep. I touch the sparse, unlikely hair there, and his shed-rummaging, car-fixing, dirt-crumbling smell comes away on my fingers. “What did you fix today, Daddy?” “Don’t worry so much, my sweet baby. Sleep.” His sweat shirt smells of front-lawn Bermuda grass and summer skin. There is the coarse, oily smell of his head and neck. Mommy and I groom him each month, lay him down on the couch like a large dog to squeeze his pimples, tweeze his splinters, rub his back. “Why is dandruff flaky if it comes from oily scalps, and how does the stock market work?” I ask. He tells me both answers every night, and I fall asleep before he finishes.

His man’s body is pure capability. His legs are hard, with bulging veins from too many late shifts at the deli. His beard is humid and hides secrets. Half his face grows old unseen. He slips on baggy white underwear after his shower, after swiping the towel between his legs, around his penis and under those long-hanging, dark-wandering, wrinkled-like-small-brains, packed-on-a-pillow-of-black-hair balls. Why are they so big, and where do they go when he sits or rides a bike?

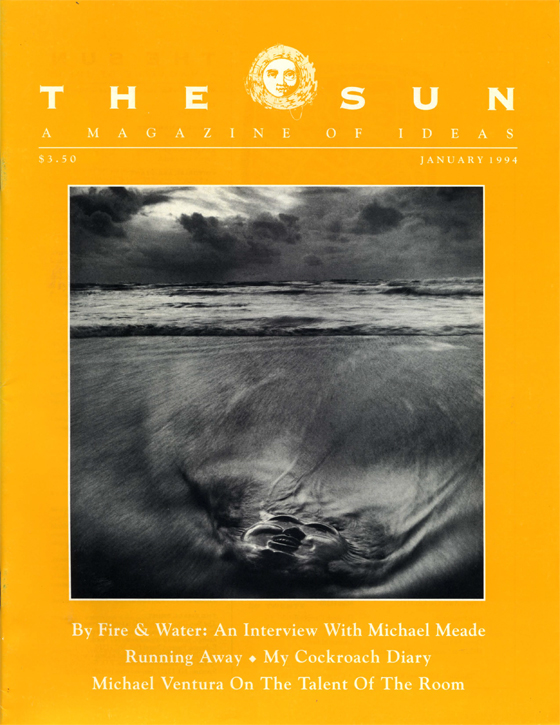

He’s the friendly giant who lies with us until we fall asleep each night, me on one shoulder and Julie on the other, the evening news from the den like a lullaby, the dog curled on the bedspread at his feet. His huge hand is on my back, my leg over his hip. I feel his chest slowly rise and fall, and I try to stretch my short, quick breaths to match. When I lean into him it is like leaning into a wave, or a mountain, or a thick, warm cloak of largeness that stands guard against the dark.