All my life I have made annual weekend trips to Montana’s huckleberry country, first with my parents, later with my own children.

Occasionally, I’ve had people along who don’t quite understand the value of huckleberrying. One year, I went with a college friend who was majoring in business. Randy swore at the endless flies and mosquitoes that assailed him whenever he stopped to pick; then he started in fiddling with numbers in his head: the tanks of gas to drive to the woods, the hours spent on the hillside, the total gallons of berries we ended up with, and several other pieces of data, all of which he added and divided and arranged until he knew for certain that we had been fools. He proved it to me, mathematically.

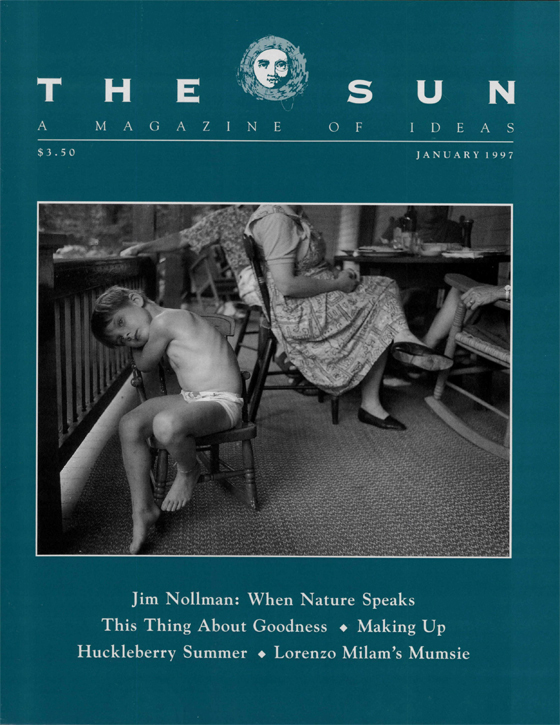

Then there was Daniel, the two-year-old son of a friend, who came with us one summer. He had little experience of deep woods and found something ominous and frightening about the dense tangle and the drizzly rain. Like Randy, he fussed and fussed all day, wanting something other than this outdoor world.

Of course, Daniel just needed time and help to find his way. My oldest daughter, Christa, held him on one hip and walked slowly through the woods, putting delight in her voice as she pointed things out so that he would understand he was in a good place. She was home from college for the summer, and I remembered her, even younger than two, peeking out from a tent at the rain, needing to be told which things in the endlessly complicated world around her were worth wanting.

But Randy probably just needed to get out of Montana. He lives in Seattle now, where the world has been improved beyond help by people with his way of thinking. Randy also couldn’t understand one of the minor art forms among Montana newspaper columnists: the comic tale of woe they tell each year as they head out to save money by hunting for free meat or gathering free firewood. I’m the same way. We like to laugh at our irrationality, at justifying $22,000 four-wheel-drive trucks so we can drive into the hills in November to bring home a carcass or two. We like to be amused by the wood-gathering trip on which we puncture a $250 tire, put a $750 dent in the truck, and back over a $450 saw before safely making it home in a mood of enterprise and thrift with our $75 cord of wood.

We have to laugh, because laughing is our way of shoving economic reckoning back against the wall so we can feel free to do the things we want to do. We have no intention of changing our ways. Randy misses the point. The columnists aren’t making fun of their financial foolishness so much as they are making fun of the abstract emptiness we are left with when we apply economics to anything so fundamentally irrational as joy.

When my oldest boy, Eldon, was nine, he came down the hill with about a pint of berries in his can. He’d seen buyers’ signs in Hungry Horse, and he was beginning to understand the uses of money. “How much does a trampoline cost?” he asked.

“About three hundred dollars.”

“How many gallons of huckleberries is that?”

“About twenty.”

He looked at the berries in the bottom of his can, hesitating on the brink between two worlds. Then he poured out a whole handful and put them all into his mouth at once.

Fortunately, it isn’t even necessary to love the luxury of a mouth overfull with berries to understand. As I remember it, my father never did pick or taste a huckleberry. Still, every summer he took us back to the huckleberry place, a parking spot beside a small creek in the vast and heavily logged ridges of the Flathead National Forest south of Hungry Horse Reservoir — the common people’s woods. While Mom and we six kids fanned out from camp in eager search of a magical patch, he sat in the shade beside his car, listening to the radio, content to be away from the maddening workdays that began at five and ran till midnight — days filled with things breaking, bills arriving, people making messes or bustling to clean them up. He certainly wasn’t there to participate in the economy, through saving money, or utilizing a resource, or any other forsaken business.

For lunch, he made us a pile of baloney sandwiches, in his neat and impeccable way. My mother, on the other hand, tended to throw things together, whether a sandwich or a conversation. She had buckets and styrofoam coolers and canning pots into which we poured gallon after gallon of berries, and she measured the success of our trip by the quantities we collected. She had always been poor, and this left her with a frantic habit of accumulating and storing.

Dad, of course, had never been poor, lacking the knack for it. He trusted that what he needed would come or could be found, and he didn’t like cluttering his house and his head with either worries or belongings. He could always afford time to enjoy leisure and peace; she was always noisily engaged in the moment’s crisis.

For a few years, their contrary temperaments were amplified on our trips by the presence of Earl Dunn and Mrs. Dunn. I never really knew why they began going to the woods with us. Huckleberrying was the only time of year we ever saw them, and their own children were long grown. Earl was a thin, whiskey-drinking man who dressed like a cowboy. He liked to sit and laugh at things, always near a cup of coffee in the mornings and a cup of whiskey in the evenings. Mrs. Dunn was a huge woman who moved in a swirl of activity. She always wore pants, her hair was cut short, and she had a tough, aggressive way of talking. She didn’t think things or wonder about things — she knew things, and she told you so. She wagged her finger at you and nodded her head as she spoke. It would take a braver person than any of us were to disagree with her. Earl said little, sitting at the edge of her whirlwind presence with his cup, grinning now and then and mumbling quips that she pretended not to hear. “What’s that?” she’d accuse.

“Nothing. Nothing,” he’d mumble, flashing a conspiratorial glance at us.

Mrs. Dunn lived the culture of huckleberries. She had a special bucket that she slung on her hip from an oversized belt adjusted to keep the rim at just the right height. She also had a berry picker — a coffee can with its open edge cut into fingers — which she could sweep over a bush, theoretically plucking dozens of berries in a single swoop. She would talk about berry patches she had found over the years, master pickers and their methods, recipes, and how many gallons she had gotten on trips going back to before I was born.

I never did find out why, once each year, the Dunns suddenly appeared and behaved as though they were our close friends. For a while I thought they came berrying with us because Mom wanted Mrs. Dunn’s reinforcement and Dad wanted Earl’s helpless company. But now that I’m old enough to understand berrying better, I think it’s more likely that my parents simply understood that Earl and Mrs. Dunn needed to join a family, to share some work with others. It helped to believe the work was important, but, in truth, it mattered less than the sharing.

So while Earl and Dad hung around camp, Mom and Mrs. Dunn and we kids barged through the woods, hollering for others to come share our good luck when we stumbled upon or tumbled into an especially good patch. We’d meet at odd intervals as our meandering searches led us to cross paths. “The berries this year are as big as your thumb,” Mrs. Dunn would say every year, thrusting her thumb at us with an emphatic nod of her head.

All day long we would pick, seeing places we would never have seen had our mission not drawn us out of our daily routines. We filled cottage-cheese containers and old ice-cream buckets and coffee cans, and we poured them into the bigger containers in the back of the red 1965 Volkswagen that we’d all crammed into for the trip. We drank water straight from cold streams. We ate berries by the handful. We studied squirrels and chipmunks. We ran across deer.

It was wilderness to us, though we parked our car in the middle of it. Occasionally, another car would drive by, but for the most part we stayed there beside the road without seeing or being seen by anyone. The first wild elk I ever saw came out of the woods into a clear-cut above our camp. The bull and two cows walked with regal slowness across the open ground, pausing to browse and look around as they picked their way, unafraid, through our field of vision and back into the forest. I knew I belonged there.

I take my own children to the same general place, although I’ve never been able to find the precise spot where my family once camped. I’m sure I would still recognize it: the huge rock, higher than a house, leaning over a ring of melon-sized stones where we built fires; five-inch trout darting at tossed scraps of baloney in the pool at the bottom of the small waterfall. It was right by the road, but the roads have been remade.

So now we choose another place, better in many ways than the one for which my dad settled. Ours has a bigger, wilder creek. It is farther from a main road. The woods are less obviously logged. We go there every year to pick huckleberries, though not so many that it feels like work, and not so we can tell ourselves we are saving money. We all know, without needing to say so, that the trip is a pure and simple celebration.

When my five children fan out, no longer needing my encouragement or help, I tend not to go far before sitting down and listening to the sounds of younger voices finding what they want — not the berries, exactly, but something that without the berries they might never have known was there.

A few years ago, my wife and I took our three foster boys huckleberrying along with our five birth children. For most of the day, the boys whined and complained, picking almost no berries. But by evening, they were nearly frantic with a sense of freedom and possibility they were inexperienced at feeling. They ran up and down the mountain, daring to venture farther and farther from the fire. They could almost see, almost hear.

A bit later, an enormous full moon rose over the nearby mountains, and it was bright enough to see colors at thirty yards. We ran up the road, throwing wild shadows through the trees, intoxicated by the sheer exuberance of the earth. The world felt in order, even the night blessed with a portion of the light.

My foster boys didn’t know their own father. I had no illusions that a night in huckleberry country would give them what they needed. But it might have let them taste a little of what they needed, so that when other chances come they will recognize the taste, and follow it.