All the ground belong to our brothers the English . . . to build a fort or to plant corn or any other use the white people may have for the lands — We wants no matter of goods or any other pay for the Lands it is already your own, We are nothing of our selves, and were you to forsake us . . . we should be both lost and naked —

— Black Dog to George Pawley in A part of A Jurnell of my Agency to the Charokees 1746

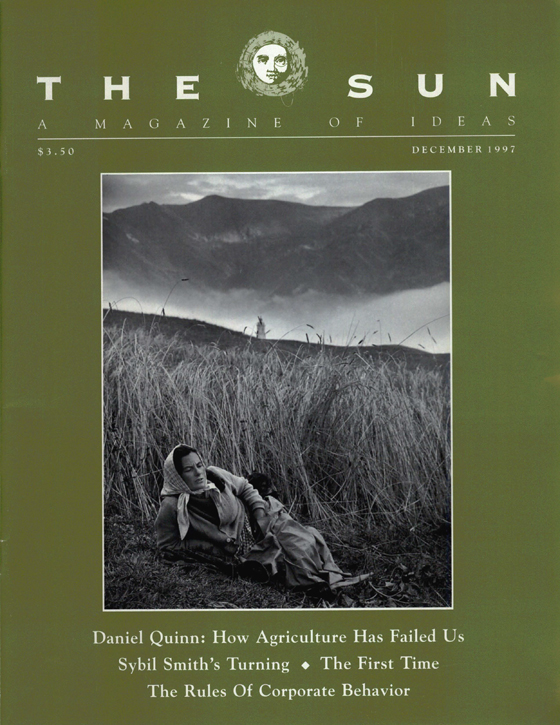

White clover saturates unmowed lawns in June. Blue mountains collect a cool silver shroud over this quiet cove as I bike downstream where my neighbor, half his colon removed, pushes a wheeled rotary blade over his territory, snarling gasoline engine proclaiming his domain. If he stalls we hear nothing but the sigh of a stream, idle opinions of birds, a squirrel hot as a high-school boy on my porch screen. It starts again, the drone of one idea. I turn on television, fighting fire with fire, to learn about Tarzan. Who knows why earth is so easy on us, how we have survived this long. In 1746, two hundred years before Nagasaki and Hiroshima, some Indians had already given up. I am Scotch-Irish, the curled lip and cutting edge of the last wave of the twentieth century, breaking into white foam. All people are good people, and I am the voice of my mother. We are the song of the earth. In the cool of evening I hear my neighbor commanding his grandson to come back here and get away from that, coughing and falling deeply silent, a good man from Louisiana, of which there are many. Here we are together, invaders from east and west. The land is already ours. Furthermore, paper says $75 million for more better highways or else tourists will stop coming.