Little Zooey died today. Pam and I were in the backyard playing with the dogs when we heard a knock at the front door. Pam went around the side of the house to see who it was and came back a few minutes later with Zooey cradled in her arms. There was no blood, but the cat’s head hung slack, her tongue sticking out of her mouth. It was plain that she was dead. Pam was crying freely, and I felt a quick surge of grief myself.

Now, I know that Zooey was only a cat. There are wars being fought, children starving, rain forests burning. One wants to be careful. I think it was J. D. Salinger who said that sentimentality is the mistake of investing more importance in something than God does. But the facts are that her name was Zooey, and she was little, and she did die, so I’m only telling you how it was.

Pam and I have what some would deem an unusually large number of animals, although over the last year or so the population has been shrinking. First, Zooey’s brother Franny was killed on the same busy country road that today claimed his sister. Pam found his lifeless body under a rosebush in the front yard. We don’t know if he was thrown there by the car that killed him, or if he managed to crawl from the street. Judging by the extent of his injuries, I’d guess he was thrown.

A few months later, it was Beasley’s turn. Beasley was a scrawny old cat with a swayback so severe she reminded me of one of those downtrodden cartoon horses. In her younger days, Beasley had actually been a bit stout, but at a certain point she’d begun to lose weight. I eventually became alarmed enough by her emaciated appearance to take her in for an unscheduled checkup. The vet diagnosed a thyroid problem and prescribed pills, but Beasley couldn’t keep them down. The second time she peed on the living-room rug, I knew her time had come.

I called the animal hospital and tried to explain the situation without sounding too defensive. I needn’t have worried. All I had to do was sign a consent form, which they would obligingly put in the mail for me. With a quick stab of my ballpoint pen and one thirty-three-cent stamp, I consigned Beasley to her fate. Easier still, I accepted Pam’s offer to drop her off at the vet while I was safely at work.

But you can’t just blithely hand your animal over for slaughter (Beasley was originally my cat) without expecting to pay a price somewhere down the line. This was my thinking at the time: (1) There is an operation available, but it’s expensive, and there’s no guarantee it would work. (2) I have given Beasley a good life. Were it not for me (obviously a very fine person), she’d no doubt have been destroyed years ago at the animal shelter where I adopted her. (3) Even under the best of circumstances, Beasley is not an easy animal. She not only throws up at least once a day, but invariably does it in the most inconvenient places, such as on my computer. (4) We can’t live with puddles of cat urine in the living room.

This is my thinking now: (1) Beasley had beautiful green eyes. (2) I could have afforded the operation if l had really wanted to. (3) I should have been the one to take her to the vet. (4) I should have held her while she died.

I was in the third grade when we got our first family pet: a tiny gray-and-white kitten with a funny little black mark over one of her nostrils. After school, I would pedal my bike as fast as I could in a rush to get home and see her. One afternoon, I found her lying in the front yard, unable to walk.

We took her to a local vet, who examined her, stuck a thermometer in her rectum, then told us that her back was broken and that she would have to be destroyed. As I think of it now, I have no idea why he had to take the cat’s temperature to diagnose a broken back, but I suppose he had his reasons. We never did piece together what exactly had happened to the kitten. Perhaps thinking that we’d find it easier to live with than the image of her being hit by a car, my father told us that she’d probably been climbing the tree in front of our house and fallen out. I accepted this explanation because I was a kid and didn’t know any better, but at some point I began to realize that cats, as a rule, do not just fall out of trees.

Stung by this first pet experience, my brothers and I waited several years before talking our parents into getting us a dog. I wanted a collie, but my mother, nervously eyeing the living-room furniture, chose a toy French poodle, whom she decided should be named Frankie, after her favorite singer. What this intense and neurotic canine had to do with Frank Sinatra escaped the rest of us, but once you name a dog, there’s really no going back.

Frankie’s main hobby was stealing things and then hiding under a bed or couch with the pilfered item, daring anyone in the house to try to take it away from him. He had a peculiar genius for stealing those exact items that would cause the greatest family upheaval — like car keys and wallets. One evening, my parents were having a dinner party for a man who was considering buying my father’s business. Halfway through the main course, Frankie came slinking into the dining room dragging one of my mother’s brassieres in his teeth. He spent the balance of the evening guarding his prize under the table, growling softly from time to time lest anyone forget he was there.

In the early days, Frankie would greet me at the door in an ecstasy of reunion that seemed far out of proportion to the amount of time that had passed since we had last seen each other. But dogs do not measure time in hours and days. For an animal there is only here or not here. Absence or presence.

As the years went by, Frankie grew steadily more unhinged, and my father eventually gave him away. By tacit agreement, we didn’t discuss the dog much after that. Though we pretended to hope for the best, we all knew what was going to happen: that the few remaining threads of sanity to which Frankie still clung would be severed by the trauma of the move.

Not too long ago, when our pet population was at its peak, a friend asked why Pam and I found it necessary to have so many animals. Implicit in his question was the suggestion that there was something irresponsible, even selfish, about our lifestyle, as if we had too many children or something. With some irritation, I pointed out the obvious: that we hadn’t given birth to these animals; we had merely adopted them. Still he looked dissatisfied. Thoroughly exasperated, I told him that we just enjoyed waking up in the morning with lots of pets around. What could be wrong with that?

But why do we have so many pets? Wouldn’t one cat and one dog do nicely? Are we trying to make some sort of statement? Is it — on my part, at least — an attempt to compensate for the fact that I’ve never wanted to have children? Do I really enjoy waking up each and every morning surrounded by needy and importunate mammals not of my species? Because if my friend had pressed me for details on what mornings were really like around our house, this is what I would have been forced to tell him:

5:30 A.M.: Toby the Shetland sheepdog stirs at first light, ready to start his day. Since he cannot do this without us, he embarks on his morning campaign to drive us out of bed. This begins with a series of low whines and whimpers. Although Pam and I do our best to shut these sounds out by pulling blankets and pillows up around our heads, they have a cumulative effect similar to Chinese water torture.

5:42: Toby begins rhythmically tapping one of us on the face. If we are sleeping on our stomachs, he will tap the back of one of our heads. One can usually get him to desist by patting him, but it’s not possible to both pat a dog and sleep at the same time. Inevitably, the victim nods off, and the tapping resumes.

5:57: Toby stands between us on the bed and makes little backward leaps, plainly indicating the direction in which he wants us to be heading — up and out of bed. In between leaps, he makes vigorous digging motions with his front paws, much the way a bull paws at the ground just before charging.

5:59: Buster enters the room purring loudly. It’s been at least three hours since he ate the last bit of food out of his dish, and he is worried that, if much more time passes, he might actually begin to feel hungry. We theorize that he may have gotten hungry once, perhaps as a kitten, and the experience was so traumatic that he’s devoted his life to making sure it never happens again.

6:03: Buster leaps (none too gracefully, at a weight of twenty-odd pounds) onto Pam’s pillow and begins to knead her hair. As he does this, he sniffs and licks her eyelids, understanding in his dim feline way the inverse relationship that exists between closed human eyes and full dishes of cat food.

6:05: Surrender. I swing my legs over the edge of the bed and plant my feet squarely in the cold, wet spot that Jake the golden retriever has made on the floor by drooling in his sleep all night.

6:15: Morning walk. We put Toby and Jake on their leashes and start out across North Street. Halfway across the road, Toby, beside himself with excitement, leaps straight into the air and delivers a sharp little nip to my right buttock.

7:05: Breakfast. This is a complicated and time-consuming affair that has continuously evolved to accommodate various health issues and individual food preferences. Also, the pets must be separated to prevent thievery. Each of our animals would cheerfully watch the others starve to death if it meant getting a few extra pieces of kibble.

Buster eats in the bathtub. He is on a special low-protein diet for cats with kidney problems. We must buy his food, not inexpensively, from the vet. We mix it with a little water and clam juice because, in Buster’s eleven years of life, no human being has ever seen him take a drink of any kind. (This might explain why his kidneys don’t work.)

Zooey eats dry kibble in Pam’s office.

Madeline, our other cat, has canned food out on the back porch.

Jake gets a low-fat, high-fiber dog food mixed with a small amount of meat, which he eats in the alcove off the kitchen to protect him from the marauding Toby. Although Jake outweighs Toby by at least sixty pounds, he is no match for the feisty smaller dog.

Toby eats out of a bowl by the refrigerator. I’ve never timed him, but my guess is that it takes him no more than four seconds to gulp down his entire ration of meat and gravy.

7:09: Having finished their breakfasts, the dogs wander into the living room to wipe dog-food crud from their faces. They have the satisfied air of two gentlemen repairing to the parlor for postprandial brandy and cigars. Jake uses the sofa; Toby, the rug.

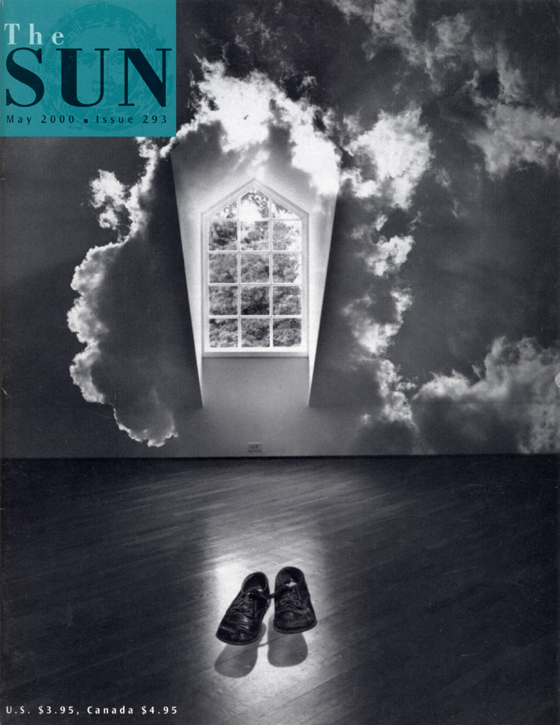

Adopt a few animals, and you’ll learn life’s greatest lesson: there is no such thing as a happy ending. I was thinking of this as I searched about for something suitable to bury Zooey in, finally settling on an old shoe box. I carried it into the backyard, where Pam sat with Zooey in her lap, gently stroking the dead cat’s head with her fingers. Jake and Toby lay nearby, panting in the afternoon heat. I took Zooey from Pam and placed her in the box: a perfect fit.

I’m no longer a young man, and these days, when death comes knocking on a summer afternoon, I pay close attention. I put my hand on Zooey’s still-warm body and lifted her head a little so that I could peer into her eyes. I haven’t been around dead things much, and I wanted to see if there might be anything I could learn there. The dogs, too, seemed curious, especially Toby, who returned to the box again and again to sniff the corpse. Toby and Zooey had been great pals, often chasing one another around the house and conducting wrestling matches on the living-room couch. Although their play could be rough, and Toby is famous for his hair-trigger temper, the two animals almost never fought for real.

I carried Zooey in her cardboard coffin to the place in the far corner of the backyard, just behind a bed of day lilies, that serves as our pet burial ground. Franny is there, and Monroe, a gentle black-and-white male who survived a fight with a neighborhood rival only to succumb a short time later to feline leukemia. Pam and I took turns with the shovel. The hole we needed wasn’t very large, but we made slow headway against the rocky soil.

While Pam was digging, Toby returned to the box for another sniff, only this time he suddenly jumped back. Evidently, Zooey had been dead long enough to begin smelling like it. After that, Toby stayed a good distance away and didn’t return until Zooey was safely in the ground.

But Toby has never been bothered by dead animals. In fact, he likes dead animals. More than once, he has come upon some rotting carcass or other and, before we could stop him, flipped over on his back to cover himself so thoroughly in malodorous ooze that only hours of scrubbing could wash out the stench. And I do not think it was the scent of more recent death that disconcerted him. He routinely inspects freshly dead groundhogs and squirrels with the greatest of equanimity.

It seems that it was the death of a familiar that made the crucial difference. Was it possible that Toby, confounded by two opposing scents, that of the live Zooey and that of the dead, had experienced a kind of cognitive short circuit? And if so, wasn’t it, in essence, pretty much the same thing that happens to people when confronted with the seeming impossibility of the sudden death of someone they know? Pam says I overinterpret the behavior of our pets. She’s probably right. All I’m really sure of is that the longer I am around animals, the less important our differences seem.

As Pam carefully placed the box containing Zooey into the ground, I thought of a poem by Rilke that I find so painful I usually skip over it in anthologies. It’s called “The Panther,” and it reads in part:

From seeing the bars, his seeing is so exhausted that it no longer holds anything anymore. To him the world is bars, a hundred thousand bars, and behind the bars, nothing.

I wondered why I should think of this now. Zooey was no panther, and it was her very freedom to roam that had done her in. Perhaps my subconscious called the poem up to assuage my guilt over letting our cats wander the countryside. We live in a rural area, and the back of our house faces acres of open pasture: a kind of feline paradise. In front, however, there is the harsh reality of the road. But isn’t it better by far to live fully and risk early death than to endure anything like the panther’s terrible death-in-life? Then again, cats who stay in the house have good lives, too. The trick is to make sure they never develop a taste for the outside world.

More likely, remembering the poem was a relapse into a bad habit I thought I had conquered of tormenting myself with images of animal suffering: the dog I once saw lying in a cage waiting for the vet to get around to euthanizing him; the bird I encountered that had become trapped in some carelessly thrown-away fishing line. It is as if I feel I owe these creatures an apology, in just the same way that I actually do apologize, ridiculously I admit, to any animal I see lying dead in the road. I’m sorry, I reflexively whisper as I jog past a flattened squirrel, or drive by a furry patch of ooze that used to be a skunk. I’m sorry, not because I had anything to do with their deaths, of course, but simply because an animal who was once alive is no more. I’m sorry for any suffering it had to endure. I’m sorry that this is the way the world works — as if there were anything I could do about it.

It was about an hour past the animals’ supper time when Pam and I finally threw the last shovelful of earth into Zooey’s grave and finished smoothing out the dirt on top. As we headed back toward the house, Jake picked up the tennis ball that we had been tossing for him earlier in the day. It was a slimy old ball, the fuzz all worn off, its original bright yellow faded to a greenish black.

Jake’s getting to be an old dog now, and he often walks with a limp brought on by too many hours of playing fetch across our sloping back yard. The vet warns that if we’re not careful, Jake may someday do himself serious injury, so we try to limit such activity as much as possible. But Jake loves it so much it’s hard to refuse him. Now he held the ball in his mouth, his soft, intelligent brown eyes looking up at me pleadingly. I hesitated before taking the ball, then threw it as high and as far as I could.