The angel went dragging himself about here and there like a stray dying man.

— Gabriel García Márquez

Pittsburgh, at the end of another terribly hot day in an unending string of terribly hot days, is a forge, the air like damp, tepid gauze. The people on the streets look stretched, desperate, short-tempered. My poetry reading, part of the eighteen-day Bloomfield Sacred Arts Festival, is being held in the Bloomfield Art Works, a small, un-air-conditioned gallery on Liberty Avenue. Its walls are covered with “sacred” art, mostly paintings, photographs, and drawings of angels. The subjects possess that characteristic ethereal androgyny, that feathery beauty that has become cliché. They are intriguing, but, in the main, I’m tired of angels.

I’m standing on the sidewalk in front of the gallery. In a few minutes, I will enter it. There, in front of an audience that includes twenty-six relatives from my father’s side — most of whom range in age from seventy-three to ninety-three — I will recount, for the first time in their presence, my version of the truth, risking my identity before these people who have known me literally all my life. Bullshit, the rhetorician’s ace in the hole, will not fool any of these folks. They’ve changed my diapers. They’ve washed my mouth out with soap. They’ve kissed these mendacious lips.

I hear my name coming from inside the gallery, where Phil DeLucia — my Communion partner, my older son’s godfather, my oldest pal on earth — has just introduced me. And everyone is clapping.

When I take the mike, I see spread in front of me my extended family. Long-lived and fruitful, they swell the room — not simply because there are so many of them, but also because they are a palpable force: four generations of garrulous, gregarious southern Italians who have gathered here, for what, exactly, they don’t know. My parents are seated conspicuously in the front row. It’s nearly impossible to get all these people together at one time, except for a wedding or funeral, so this has been the equivalent of a family reunion: kissing, hugging, weeping, reminiscing. It is, in itself, a performance — a great Fellini-like, Scorsesean burlesque.

My reading is memorable only for the heat. The half dozen ceiling fans do nothing but circulate the hot, swampy air. Nevertheless, my family would rather be cooked than miss this dubious event; it is a matter of honor. (In fact, my eighty-nine-year-old Aunt Lucy purportedly had a mini-stroke mere seconds before leaving the house, but could not be dissuaded from attending.) A mike has been set up so that the old people can hear, but it malfunctions. As I literally shout what seem to me my terribly self-conscious poems, the audience members fan themselves with their programs and strip off as much clothing as possible. I feel little rivers of sweat running down my torso; my drenched white shirt grows heavier. All about me, the angels melt, their smiles turning to grimaces. Like the rest of us, they have been remanded to purgatory.

Mercifully, I lose my voice and have to wrap things up early. With arms around my two oldest relatives, Aunt Lucy and Aunt Gina, I walk out onto the avenue, which, compared to the gallery, is refreshing. My father’s sisters tell me how proud they are.

“You were always a good boy,” Aunt Lucy says.

Incredulous, Aunt Gina retorts, “He was a bad boy.”

I thank them both and give them big kisses, just happy the whole thing is over and nobody died of heatstroke. After seeing off my wobbly parents and aunts and uncles, I walk with my old friends, who have also come to the reading, down the street to Del’s, an Italian restaurant. All I can think of is air conditioning and beer. On the way, we have to pass Saint Joseph’s Church. Standing shakily in front of it is a man, clearly drunk, dressed all in sky blue and sipping from a quart of beer. He smiles and waves, and we wave back.

With me is Richard Infante, a buddy from high school and a writer himself. Richard became a Roman Catholic priest relatively late in life, and I haven’t seen or talked to him in years. As we sit at the restaurant, he explains that he was late to the reading because he was hearing confessions. Suddenly talk swerves toward that most daunting of sacraments, and someone remarks to Father Richard that, in his role as confessor, he probably hears some outlandish tales.

“You wouldn’t believe,” he says. “From little things, like telling a white lie, or having a nasty thought about your neighbor, to really bad things — even crimes.”

“What if somebody came in and told you that he’d killed someone?” Phil asks. “What would you do?”

Without hesitation, Father Richard replies: “I am bound by my vows not to divulge anything I hear in the confessional.”

“What do you tell people who trot out these piddly little sins, like lying?” I ask. “Do you tell them to forget about it?”

I am thinking of all the times I obsessed as a child over tiny, inconsequential transgressions, things that I now hardly consider sins. Human foibles: the kinds of imperfections that are inescapable, even endearing.

When I was a kid, everything was a sin. I used to get physically sick contemplating confession. So sold was I on the fact that I was a bad boy, a sinner, that I became absolutely immobilized with terror on the eve of my first confession. My Uncle Dick told me that I’d better take my lunch, I’d be in there so long; that, instead of Our Fathers and Hail Marys, I’d be sentenced with the Stations of the Cross.

I remember once bringing into the confessional a little booklet, given to us by the nuns, which listed every potential sin. Beside each one I’d written the number of times I had committed it. But inside the booth, it was too dark to see what I had written, so I had to wing it.

By an early age, I had been made into a hopeless neurotic by the sacrament of confession. I was so preoccupied with the cleanliness of my soul that, at one point, I went to confession every day until Father Battung, in a startling breach of confidentiality, addressed me by name and told me not to come back again for a month. On another occasion, when I confided that it had been “a while” since my last confession, Monsignor Hayes told me I was excommunicated — loud enough that my classmates waiting in line outside the confessional were laughing when I emerged, disgraced and mortified.

By the time I turned thirteen, in 1966, the sacrament of penance was simply too much for me, a burden I could no longer shoulder, a masquerade I could no longer pull off. Though still innocent enough to receive a Peanuts birthday card commemorating my entry into my teens, I was also in the throes of puberty. By the letter of the law, I was guilty of sins that had to be confessed if my soul was to be salvaged — not just venial sins, those misdemeanors that could be seared off in purgatory, but mortal sins that would be punished with the spiritual equivalent of the electric chair: eternity in hell.

For instance, I was polluted with “impure thoughts.” Could I make a clean breast of this to Monsignor Hayes, a fierce, red-faced, bad-tempered man whose starched black cassock denied the very existence of genitals?

In the confessional, I found myself withholding all of my mortal sins (banal and benign though they were) because I was too ashamed and afraid. The irony was supreme. By lying about my sins, I was digging a deeper and deeper pit for myself. I was sinning even as I went to confession — in effect, perjuring my soul.

After a while, my angst and my conscience got the better of me. I couldn’t take the vicious cycle of sin and lies. The entire sacrament seemed a setup, a sucker’s game in which I could only fail. So, like a spouse in an abusive marriage, I packed what little I could carry and took off. No more confession for me.

I became a lapsed Catholic, my self-imposed exile resulting ultimately in an unofficial, yet very real, excommunication, much more serious than the kind Monsignor Hayes doled out when he was in a bad mood. I didn’t feel good about jumping ship, but I didn’t feel bad about it either. I had to do it in order to survive. Leaving the Church was the only way I could salvage my sanity; the stakes were that high. Besides, back then — and even now, although I currently attend a Baptist church — I never felt as if I’d forsaken Catholicism. Maybe I’m guilty of sacrilege, of attributing a kind of regular-guy empathy to God, but I’ve always been sure that he understands, and is maybe a little cynical of the entire process himself.

In Del’s, while I devour my fiery chicken diavolo, Father Richard finishes chewing a bite and responds to my question about “piddly little sins”:

“It doesn’t matter whether I think what I’m told in the confessional is serious or irrelevant. What’s important is that the people confessing want to be unburdened of what’s troubling them, no matter how big or how small. They want to be forgiven, to be made whole again by God’s mercy. My job is simply to listen and to be an instrument of that mercy. I can’t tell them that they’re worried over nothing, or to forget about it.”

I and the other lapsed Catholics at the table, whose estrangement from Catholicism at least loosely parallels mine, gaze at our buddy, who hung in there and became a priest. A good priest, gentle and nonjudgmental. The kind one could tell anything without fear of reprisal. “God’s mercy,” he said, not, “God’s wrath.” The nuns, our chief tutors in matters of theology and spiritual fitness, never explained the sacrament of penance as existing to make the penitent feel better. I always thought it was designed to make you feel worse; to scare and scar you so deeply that, rather than absolve you of sin, it extorted sin from you through ritual degradation. Even our Protestant wives seem impressed by Father Richard’s testimony. They have been listening to our horror stories about confession for years.

After leaving Del’s, we stroll up Liberty Avenue toward our cars and linger in the sticky shadow of Saint Joseph’s to chat a little more. The drunk who waved to us earlier is passed out on the steep concrete steps leading up to the church vestibule. It’s about 1:30 in the morning. The bars are sounding last call. From their doors come flashes of light and snatches of murky conversation as people straggle out.

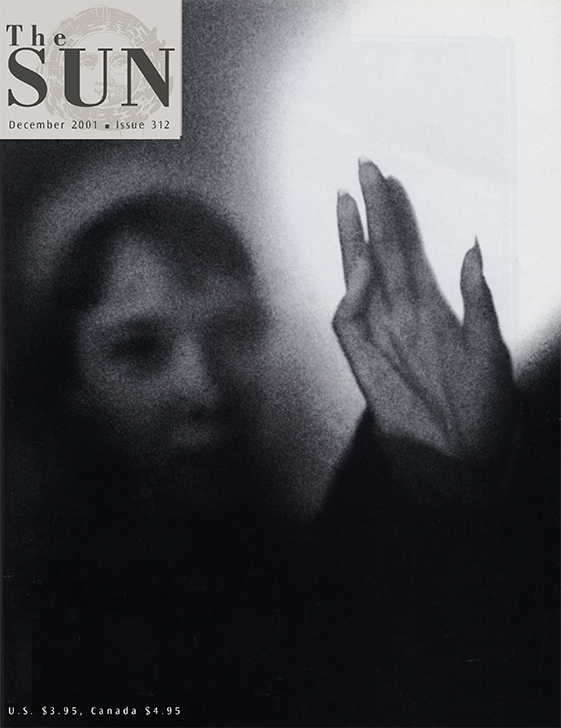

We say our protracted goodbyes, and everybody takes off except for Phil, my wife Joan, and me. We cross the street to the art gallery, where our car is parked, and look at the angels on display in its windows. My wife is arrested by a life-size oil painting. The angel’s outstretched arms, wind-whipped robes, and long, frothy hair together create the illusion of ascension. But its eyes are filmy, sunken in plastery sockets. The angel is blind, and its tunic is shorn from one shoulder, exposing a full, female breast. Like lingerie, its wings drip from it.

I lean against a parking meter and stare at my wife, her hair turned to marble in the avenue’s dank, industrial light, her dress glowing as she seemingly levitates, staring at the angel, who stares sightlessly back. Pulling on a cigarette, Phil stands next to me, his eyes, too, fixed on Joan and the window.

“Hey, man, can you spare a smoke?”

I turn around and there he is, the man we saw sprawled on the church steps. He lists dangerously one way and then another but, like one of those bottom-weighted punching-bag toys, somehow keeps from keeling over. Phil forks over the last cigarette from his pack.

“How about one for the road?” the man asks.

Phil turns the empty pack upside down and shakes it. “You just got one for the road.”

The guy seems amused by this. He smiles, plants a foot that threatens to walk off without him, and asks sheepishly, “Can I get a light?”

His words come out in shambling hiccups, slurs, and burbles. He’s a parody of a drunk, like Crazy Guggenheim on the old Jackie Gleason Show. With some difficulty, he finds his mouth with the cigarette; Phil holds the lighter up to it, but, staring down his nose at the fire, the man gets the shakes so badly that Phil can’t get the cigarette lit. The drunk starts crying — an all-out, shameless boohooing, like some four-time loser in a film noir trying to weasel out of his comeuppance. Embarrassing even for the hit man. Pow.

Phil takes the cigarette, lights it himself, sticks it back in the man’s corrugated mouth, shakes his head, and walks into the gallery. He does not suffer drunks well.

“I’m sorry,” the man says, dragging on the cigarette, trying to compose himself and get his ballast. “It’s just . . . I’m sorry.”

“It’s OK,” I say.

He’s probably my age, rumpled but not cruddy, with a half-moon belly hanging above his sagging belt line, a thatch of sandy hair, and the face of a koala.

“Can you spare a couple of bucks?” he asks.

This is inevitable, the point in the narrative where I have been coached to walk away or tell him to get lost. A cigarette is one thing, money another. But I sold a few books after the reading, so I have a stash of bills in my pocket. I peel off two bucks and hold them out to him. He extends his arm to take the money, but his balance again forsakes him, and he begins to capsize. I grab him and stuff the bills into his jeans pocket.

“Thanks, man,” he says. “Thanks.”

Then his pupils dilate as if he’s just seen Beelzebub, wearing a Steelers T-shirt, walking down Liberty Avenue and beckoning to him. A look of terror hacks out of his eyeballs.

“Oh, God,” he weeps, tears coursing down his face. “I’m sorry. I’m so sorry. I’m bad. Oh, God.”

“It’s OK.”

“I am so sorry. I am so bad.”

“No, you’re not. You’re OK.”

“Just gimme a hug,” he says, his voice thick and boozy, as if his mouth were padded with gauze. “Can you just gimme a hug?”

As we embrace, I am subsumed in his disequilibrium, forced to sway along with him. He holds on far too long. On his back, through his sweat-soaked shirt, I can feel the raised scars where his wings have been amputated. Over his shoulder, I see Joan in the gallery doorway, crying softly as she watches our strange dance. Behind her, the blind angel reaches out into the Braille night.

A touch of vertigo settles wetly over me. The man won’t let go, and I want him off me. My city instincts flash: what the hell am I doing hugging an inebriated vagrant at almost two in the morning? I suddenly feel a little panicky. I’m ready to hit him if I have to, but he’s still sobbing, “I’m sorry,” over and over, so I peel him off me as gently as I can. Joan has vanished into the gallery.

“I want to sit down,” the man says. “I just want to sit down.”

I muscle him over to a cafe stoop, ease him down, and prop him against a wall.

“I’m sorry. Oh, God, I’m so sorry.” His sobs subside into whispery soughs.

“It’s OK. You didn’t do anything,” I say, absolving him one last time. No need to hit him with a penance; he is already saddled with a ponderous one.

By now, he is exhausted, like a child who, in his desperate contrition, has cried too much, too long, and has no idea what’s really wrong or how to fix it. In a swoon, he tilts over to the concrete floor. I add a ten-dollar bill to the two dollars already in his pocket: good money after bad. Twelve dollars down the drain. What the hell. You can’t get much of a meal — or much of a drunk — on a couple of bucks.

Not just a handout, the money is both alms and payoff. I leave it in his pocket because he is the dispossessed, heartsick, homeless derelict in the street, and I am not. My savior, he suffers in my place. Therefore, I must love him even as I fear him. At the very least, I must forgive him. Twelve dollars seems a small price to pay to keep him in the gutter instead of me.

Joining Phil and Joan in the stifling gallery, I shamble around looking at the art. On the wall just behind the podium hangs a huge, smoky blue oil of the Blessed Mother. Superimposed over her left eye is a pale yellow gossamer square. Before the reading, two nuns stood before this painting, and I overheard them discussing what the yellow square was supposed to represent. They eventually fixed it as a symbol of Mary’s inner light — which, I thought, was a touch oversimplified, though I couldn’t come up with anything better.

After the reading, during the question-and-answer session, one of the nuns asked me why I write — a question I dread because, like most writers, I don’t often think consciously about the matter; the answer lies inscrutably embedded in my work. Also, in responding to such a query, there always exists the potential to make a pedantic fool of oneself, especially with one’s perspiring extended family looking on. Leave it to a nun.

A few years ago, in the mountain town of Asheville, North Carolina, I walked into the beautiful Cathedral of Saint Lawrence, situated portentously on a shimmering hill. It was a Saturday afternoon, and outside each confessional was a line of penitents. Hesitant and fearful, I slipped into one of those lines. When my turn came, I planned to kneel down in that box and say, “Bless me, Father, for I have sinned. My last confession was thirty-one years ago.” Then I was going to spill it all, no holds barred, and emerge with a sparkling soul.

But the line moved slowly, and I had to be somewhere at a certain time, and, in the end, feeling no small relief, I hustled out of the cathedral. Despite my considerable education, my worldliness, and what I regarded as my well-thought-out spiritual beliefs, the prospect of confession still traumatized me.

So my response to the nun’s question surprised even me: that I wrote because it afforded me a chance to be a better person, to see and speak the “truth” that is perhaps invisible during the actual experience I’m writing about. “I write,” I said, “to be forgiven.”

And there it was, perhaps what everybody is looking for: Another chance. Absolution. What Father Richard termed “God’s mercy.” Isn’t confession central to the human psyche? Perhaps only in telling the story of our (perceived) transgressions can we obtain forgiveness — and go on.

Inside the gallery, I can’t look at any more angels, and I especially can’t take the heat. The three of us walk back outside. The drunk is gone, disappeared into the pitiless city. Traffic has picked up dramatically. Cars zip out of alleys and side streets to flood the avenue. The sidewalks are crowded with people.

“What’s up?” I ask Phil.

“Bars just closed.”

All throughout Pittsburgh, and in every city and every town on the East Coast, people who have spent the night drinking in bars are taking to the highway. And all but a handful make it home.