The charming and handsome serial killer Ted Bundy was executed on my birthday. Something about this fact brings birth and death full circle for me. I remind myself of this today, my birthday, as I am making dinner for my boyfriend, Lenny.

My mother brought me up to believe that you are supposed to give gifts on your birthday, not just receive them. She has always been a great believer in reciprocity. This dinner is my gift to Lenny, who took care of me in the weeks after I had my hysterectomy. My mother would be proud.

Lenny was not as good as my mother would have been at taking care of me, but he tried. Sometimes he didn’t think about the little things you cannot do for yourself when you are ill. He did the big things, though, like feed me, feed my cats, cut wood for the winter, and fix things around my house. Lenny is always fixing things around my house.

One day I said, “Lenny, there’s a crack in my bedroom wall.”

This was after I had been in bed for about a week. The crack in the wall was driving me crazy.

“Where?” he said.

“Right there,” I said.

I live in a hundred-year-old farmhouse, which might sound homey and quaint, but it’s not. My house has no style or grace, and it has a lot of problems. Lenny keeps saying the house will grow on me. I don’t know about that.

Lenny examined the crack in my wall and said, “I’ll fix it tomorrow.”

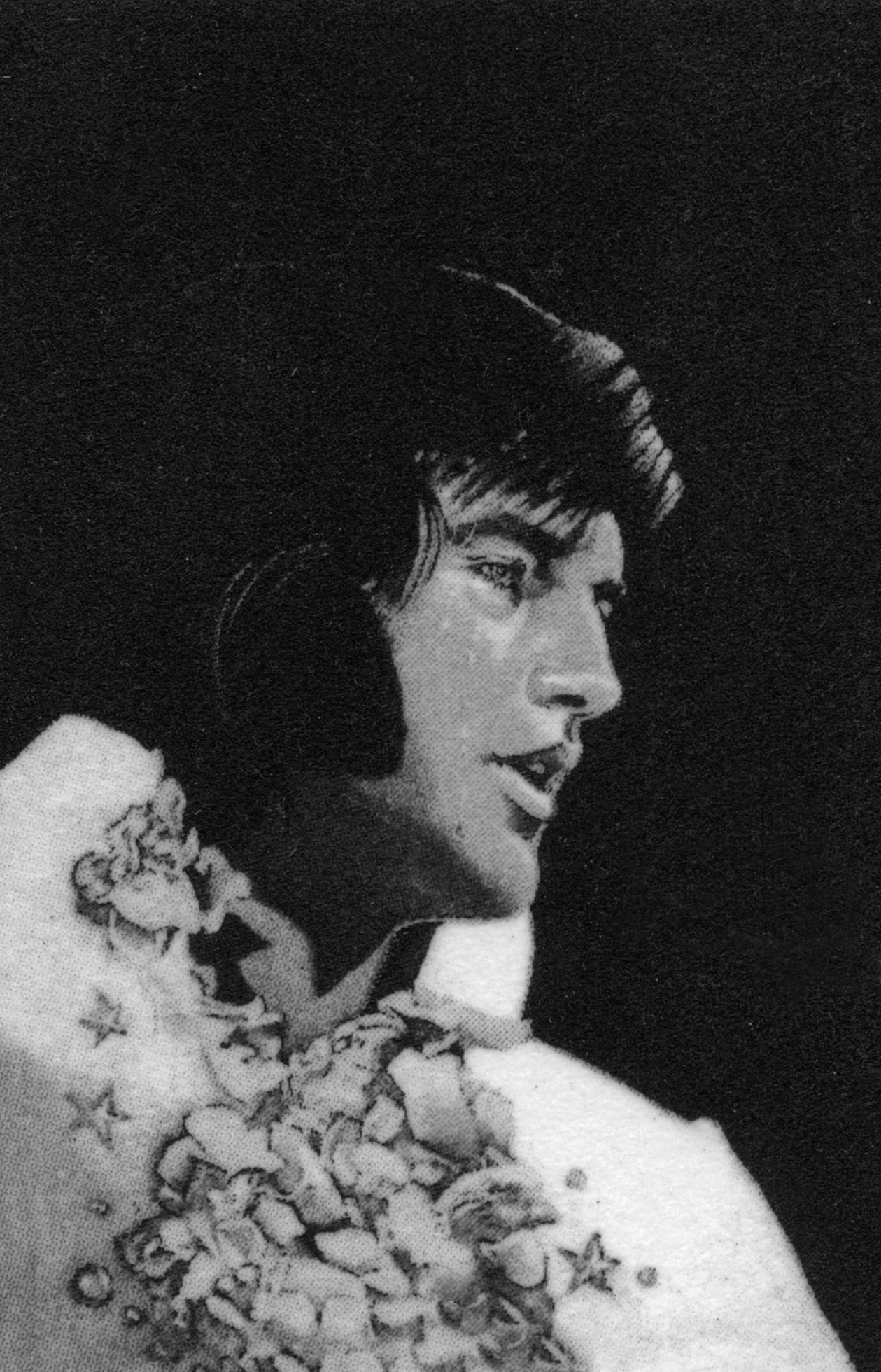

The next day he came over with a big velvet Elvis painting and hung it over the crack.

“I don’t want that ugly thing,” I told him.

“Sure you do,” he said.

“I want the wall fixed,” I said.

“It is fixed,” Lenny said.

“That velvet Elvis isn’t fixing anything,” I said.

“Elvis would be hurt if he heard you talk that way,” Lenny said. “I paid three whole dollars for this.”

And then, due to some mix-up between my brain and my mouth, I called the painting a “Velvis.” I said, “That Velvis has got to go.”

The Velvis became part of our standard repertoire of jokes.

I said, “That’s not even Elvis. That’s Elvis’s cousin, Velvis.”

“Yeah,” Lenny said. “It don’t even look like Elvis.”

And I said, “Yeah, and those people in Las Vegas, they’re not Elvis impersonators; they’re Velvis impersonators.”

I happened to have on a blue nightgown, and Lenny sang, “She wore bluuuue Velvis.”

A day or two later, I said, “Velvis. It sounds like a woman’s body part.”

“Don’t let them take your Velvis,” Lenny said.

“Why not?” I said. “They took everything else.”

We made so many jokes about the Velvis painting that I started to like it. It is still hanging over the crack in the wall.

I have always been attracted to blue-collar men, men who work with their hands. Nothing represents potency to me better than somebody doing hard physical work.

Lenny is a jack-of-all-trades. He can build or fix anything. He has told me that the crack in my wall is just the beginning of this house’s problems. “You don’t fix somebody’s big toe when their whole leg needs to be whacked off,” he said.

That is why I have the Velvis and not a crack-free wall.

Lenny arrives for dinner at six o’clock, flowers in hand. Lenny always smells nice and clean. He tries to wrap his arm around my belly, but I do not let him. That’s because I’m picturing in my mind what my scar looks like. Sometimes, when I go into the bathroom, or even in public restrooms, I raise my shirt and look at my scar, which appears garish and ugly in the harsh light. It divides me down the middle in a way that troubles me. I do not like the idea of being divided.

Lenny dresses in jeans and boots and always wears some kind of wide-brimmed hat. Some people, especially children, think he looks like a cowboy. I don’t think he looks like a cowboy. That would be too much in the way of potency for me.

I take the flowers to the kitchen and put them in a vase, but, truth be told, my heart fell as soon as I saw they were carnations. I have never liked carnations, having seen too many of them at parades and funerals. It’s silly, but somehow I was hoping he would bring me lilies. I have been thinking he would all day long.

The lilies in my garden were in full, fragrant bloom, mouths open, stamens trembling, their ruby throats showing, the day Lenny drove me to the hospital in Toledo for my hysterectomy. On the way to the car, I bent down to smell one, and my nose came away covered in pollen. It made us both laugh.

By the time I was able to shuffle outside after the surgery, the lilies had shed their blooms. I took one look at the bare stalks and cried into Lenny’s chamois shirt.

They say that after a hysterectomy you have to learn to walk all over again. It’s true. I am still learning, in a manner of speaking.

There is no other way to say it: I have ten cats.

Right now, as I put Lenny’s carnations into a vase, I hear the cats meowing at the door. They do not all stay in the house at once. I let a few in at a time, alternating among them. Tonight I have put them all outside. I do not want Lenny looking at my cats. He tells me I have too many. Sometimes Lenny tries to convince me to take a couple of them to the shelter. He tells me they do not kill cats at the shelter in Bowling Green. That is true about the shelter, I think, but I’ve heard that sometimes, when they get too many animals, they give them to other shelters that do kill them, or to labs for experiments.

Lenny tells me I am crazy to have ten cats.

An old gray tabby has been skulking around my place. He would make eleven, if I could get him to stay. He has a shaggy coat and shredded ears. I have often complained about him to Lenny because I don’t want Lenny to know that I want the cat to stay. Sometimes, to make my act more convincing, I tell Lenny how mad I am at the old tabby, because he fights with the cats I already have.

Lenny tells me I should call animal control; they would come and catch the cat and take it away.

“Yeah, maybe,” I say. “I’ll see how things go.”

The truth is, I have already partly beguiled the wild tabby with food. I picked him up once, and he did not seem to mind. He felt warm against my chest, and I heard a crackling sound within him, like he was getting fired up to purr. I felt his body poised to reverberate with pleasure. Then I brought him into the house, and the sound stopped. His heart beat fast. He jumped down and ran from room to room like he thought he was trapped. I let him out and have not seen him since. It has been a couple of weeks now. Maybe he does not trust me anymore.

When the tabby was still around, he once fought my cats while Lenny was here to see it. “Nora,” Lenny said, “you really need to get rid of that cat.”

“I know it,” I said.

After a fight, the tabby would disappear into an old barn of mine. There he would lurk for hours, maybe days. Lenny complained that the tabby was terrorizing the other cats, but I secretly enjoyed the thought of him being there, sitting in the dark barn, waiting. I wanted to tell Lenny that a certain amount of terror might actually be a good thing, that it might keep you sharp and alive. But Lenny would probably have pointed out that it was easy for me to say; the terror was not after me.

I wait and watch for the tabby’s return. Something in me needs to see him again.

Lenny is a dog person. I am uncomfortable identifying everyone as either a dog person or a cat person, but maybe there is some truth to it; all clichés were once fresh and true.

Lenny has two adopted greyhounds. He really loves those dogs. Lenny’s greyhounds are skittish and take up a lot of his time, money, and energy. It seems like they are all he wants to talk about. Lenny has taught me everything about the abuse of greyhounds. He has told me how they are slaughtered when they can no longer race. He has described a place in Florida that was grinding dead greyhounds into food for alligators and other dogs.

It is clearly worthwhile to save as many greyhounds as possible. Yet I cannot understand why Lenny doesn’t feel the same way about cats. It must be the truth behind the cliché.

Before I serve the birthday dinner, Lenny brings in some wood for my stove from the pile he spent all summer cutting for me. Lenny takes a lot of pride in the wood he has cut, and so do I.

He says, “This place is lousy with cats.” He tells me they are always getting under his feet.

Indeed, as Lenny stands there with his arms full of wood and the door wide open, Bubba shoots into the house between his legs. It has been a bitter winter so far, and Bubba hates the cold.

“Nora,” Lenny says, “if I didn’t know better, I’d say these cats are a psychological problem.”

I am thinking, My problem or his?

Lenny does not always say things the way he means them. Sometimes he mixes up words with funny results. One time we were talking about human rights, and Lenny said, “This country won’t really be free until people aren’t discriminated against according to race, sex, or sexual performance.”

I still rib Lenny about that one, but I am happy to be involved with such an egalitarian man.

I pour spaghetti noodles into the colander and say, “I don’t have a problem, Lenny. It’s not like I go out looking for cats.”

“Well,” Lenny says, “where will you draw the line?”

Why is it that people are always talking about “drawing the line”? Why are there lines and boundaries around everything?

“Think about it, Nora. You can’t take in every stray.”

“I suppose,” I say.

“You never give a direct answer to anything,” Lenny says.

I do not comment. Instead, I turn my attention to Bubba, who is rubbing against my shins. He stands on his hind legs and shoves his big head at me. Bubba has eyes like emeralds. He is a raggedy-ass mix of tabby and Russian blue. Somebody had him declawed, so I guess he had a family once. Now he tries to dig his phantom claws into the wood of my cabinet. His paws look crippled and useless. I bend down and pet him.

“All I’m saying,” says Lenny, “is you can’t go on like this. Ten cats. You have to agree.”

I say nothing.

“Nora,” he says, “you have to agree, right?”

The sauce is fine.

Really, it is a little off.

The wine has lightened Lenny’s mood, and he pours us both some more and asks with a chuckle, “How’s your Velvis?”

I tell him my Velvis is just fine.

He says, “You haven’t let anybody take your Velvis, have you?”

We joke all the time about the Velvis now. It feels good making jokes that only the two of us get.

“Nobody gets their hands on my Velvis,” I say.

“Except me,” Lenny says.

Lenny and I have not had much sex since the surgery. We try, but it is terrible. Sometimes I wonder if this is the way people feel when they have lost an arm or a leg. I have always heard that those people sometimes feel sensation in the missing part, a phantom limb, but I do not feel anything where my uterus used to be. I do not think there is any such thing as a phantom orgasm.

Really, I can see how this whole Velvis thing might get to be too much.

The thing about Velvis is that he is an impersonator. Likewise, I sometimes feel as if I am doing an impersonation of myself. Not long ago, I dreamed there were two Noras and two Lennys. One pair I thought of as Nora and Lenny. The other pair I thought of as Vora and Venny. In my dream, Vora and Venny sat on a porch swing and rocked as they watched Nora and Lenny lying together in a brown field. Nora was dying, and Lenny was watching her die. Vora and Venny knew they could do nothing about it. They were sad. But as they rocked, they knew that whatever would happen, would happen.

Thinking about the dream always gives me a bad feeling in my chest, a sick kind of tiredness. This feeling usually spreads and makes my whole body feel like empty, useless rooms.

I say, “Do you like the spaghetti, Lenny?”

“It’s great,” Lenny says. He has eaten two big plates. He looks so innocent while he eats, so vulnerable and trusting. I do not feel worthy of his trust. Watching him eat the spaghetti makes me feel bad. I know it is not my best effort. I wish he would tell me, Nora, this sauce sucks.

I think maybe it was the generic oregano that ruined the sauce. I remember the day I bought it. I usually do not scrimp on spices, but that day I felt an overwhelming need to cut my grocery bill. More than that, I felt a kind of panic. The panic settled on me, heavy and cold, like a second skin. I felt lost in the store and was unsure which way was out.

Lenny sops his plate with homemade rolls. He has started talking about his greyhounds again. I made the rolls by forming the dough into long ropes, then slicing the ropes into pieces with a knife. The dough folded into itself as I cut. Trying to heal itself, I thought. As Lenny eats, I notice that the rolls look like amputated limbs.

I try to listen to Lenny talk about his greyhounds. I want to be like I used to be. I want to care about the plight of greyhounds everywhere. They are noble, suffering animals, I tell myself. Lenny describes to me how greyhounds are beaten and starved, how they are left in hot, airless crates for hours at a time.

I should feel sympathy for these animals because I, too, feel like I am running, running, running, and getting nowhere. I do not have a full-time job. I do not have medical insurance. Since my surgery, I have been in debt. Like the greyhounds, I feel as if I am caged and beaten by life and made to run for others, having nowhere to go myself.

Yet I’m not sad about the greyhounds tonight. The stars are out, and they are pretty, and they are shining down on atrocities everywhere, but somehow I have lost the thread of why any of this matters.

Lenny and I finish our supper and go into the living room and sit next to the fire. We open the doors on the wood stove and watch the flames.

“You should be careful about sparks when you do this,” Lenny says. “It wouldn’t be hard to start a fire. This old place would really go up.”

“I know how to use a wood stove, Lenny,” I say. “I do it all the time when you’re not here.”

I say this even though I am thinking about the house in flames. A one-hundred-year-old house, destroyed by my carelessness.

“I know,” Lenny tells me. “I’m just saying.”

The fire snaps, and the logs groan. I think I might be starting to feel better. This is not really a bad night, I think. It is my birthday.

“Lenny,” I say, “what’s the worst thing that ever happened on your birthday?”

Lenny is stabbing at the wood with a poker. He likes to think he is influencing the flames in some way. He sees the fire as something he has to control.

“What do you mean?” he says. “My uncle got drunk at one of my birthday parties and beat up my aunt. That was pretty bad.”

“Oh,” I say. “That is bad.”

“Nah,” Lenny says. “It wasn’t that bad. I got over it.”

Everyone in Lenny’s family has a drinking problem except Lenny. Lenny’s ex-wife, Marina, also had a drinking problem, which is what destroyed their marriage. Before their divorce, Lenny’s wife had a stillborn daughter. Lenny blamed it on her drinking. He does not like to think it might have had something to do with his exposure to chemicals in Vietnam.

Lenny told me once that he was there when Marina had the baby. I held Lenny’s head in my lap as he told me that the room had smelled like death, that he knew the smell from the hospital in Okinawa where he’d recovered from his war wounds.

Lenny hates war. He even hates war movies. He says he is tired of death.

Even though I know he does not like to talk about such things, I say to Lenny, “The worst thing that ever happened on my birthday is they executed Ted Bundy.”

Lenny says, “Nora, I don’t know why you think about stuff like that.”

I say, “I don’t either.”

The hickory logs are sweet-smelling. I think about my cats out in the barn, lying nose to tail, folded in on themselves like croissants. I remember how my Uncle Will loved his cat Sam. Will was foulmouthed and irritable because he was sick all the time, and nobody would have anything to do with him except my father and Grandmother Bertie. Will lived with Bertie, and he loved Sam the cat because Sam didn’t care that Will was crude, that his body was disintegrating, that wherever Will sat he left a pile of dead skin on the floor.

“How do you feel tonight?” Lenny says.

“Tired,” I say.

“Really?” Lenny says. “I mean: really, are you all right?”

I think about it. I do not want to wear him out with my problems.

“I really want to know,” Lenny says.

I feel I should at least tell him something. “Well, I don’t feel all that great,” I say.

Lenny gets up and grabs a couple of logs to put on the fire. I’m glad for the fire because it gives him something to do with his hands. Lenny is the kind of person who needs that.

“Sometimes,” I say, “I just feel like somebody has hijacked my body.” My hormones have been out of whack since the operation. Lenny has told me there are times when he thinks he doesn’t know me anymore. This is too sad for me to think about very long.

Lenny throws the wood on the fire, and sparks fly out. They do not get on anything important. Most die out before they hit the floor.

“I really can’t explain it,” I say.

Lenny keeps busying himself with the fire. He pokes at it. He arranges the wood so there is enough air for the fire to breathe. He really has a good fire going — much better, I have to admit, than the ones I make.

Then he knocks the wood down, and it all lies flat and starts to smother the flames.

“What did you do that for?” I ask. “You really had it going great.”

“Nora,” Lenny says, “I have to tell you something.”

The way he says this makes me think I don’t want to hear what he has to tell me. I say, “You had the fire going just the way you wanted it, and then you messed it all up.”

“Nora,” Lenny says, “about two weeks ago, I caught that tabby, the one that was bothering your cats.”

“Caught him?” I say.

Lenny puts the poker down. “I took him to the pound.”

“Caught him?” I say again. “What do you mean?” I blink and shake my head. “To the shelter?”

“No, to the pound,” he says.

“The pound?” I ask. “But why didn’t you take him to the shelter?”

“Because the shelter was full. They wouldn’t take him.”

“But they kill them at the pound,” I say. “He’s probably dead already.” My voice sounds thick, like it is rising up through blood.

“Yeah,” Lenny says, his voice cracked and low. “Probably so.”

Lenny’s hands are on his knees, and he will not look at me. Smoke is curling from underneath the wood. It stinks. Lenny starts rearranging the wood again, but it is too late. He has killed the fire.

“Nora,” Lenny says, “I knew you didn’t really hate the cat. It . . .” He pauses. “It was wrong.”

When Grandmother Bertie died, my Uncle Will and my father went together to make the arrangements. When they came to the house that Will and Bertie had shared, they found Will’s cat Sam dead in the road. My father buried Sam in the yard and talked to Will for a while before coming home to us, his family.

For the rest of his life, my father would think about how Will shot himself that night, and how that moment of desperation might have been avoided. I’m not saying Will killed himself over his cat. I am just saying that death always factors itself into your brain along with everything else. I am saying there are different kinds of deaths. I am saying that with every death, you are supposed to look for a new beginning, but not everybody can do that all the time.

My father sold Bertie’s house, and sometimes he would go out of his way to drive past it. Sometimes he would sit in the car and look at it for a long time. Sometimes when we went out for a doughnut together, we would drive back by Bertie’s house. My father and I would not talk. I would think about Sam. I would think about the bones of that cat buried in the yard.

It’s past midnight. It is no longer my birthday. I am washing dishes. Lenny is talking about his mistake. He’s having a hard time explaining. “Sometimes I do things like that. I don’t know why,” he says. “Sometimes I just feel like I’ve got to do something. Like I’ve got to take action. The last thing you needed was another cat.”

He says he had to tell me because he does not want our relationship to be based on lies. His marriage was like that, and he is sick of lies.

“Even when I know what I’m doing is wrong, I still do it,” Lenny says. “It’s messed up.”

He tells me he loves me.

I ask him if he would like to stay with me tonight, although I do not really want him to.

Earlier in the evening I did. Before this happened, I looked forward to us lying together in my bed, me and Lenny in the room with the Velvis. Me and Lenny spooned together in my bed. I would let him touch the scar, and he would say, like he always does, “Nora, I’m sorry this happened to you.” When he touches the scar, he always says he feels the pain himself. This is what I thought my birthday would be like this year: Lenny and me and my two Velvises — one on the wall, and one in the bed.

Lenny knows me well, and that is why he will not stay tonight. He says, “Well, you know, I’d like to stay, but there’s the dogs.” He tells me how the greyhounds are just too fragile. They will not understand being left alone all night. “Trust is very important to them right now,” he says.

He tells me our lives will not always be this way.

After Ted Bundy’s execution, the National Enquirer ran a picture of his dead face. You could see where the electrodes had scorched his forehead. His eyes were half open, and he seemed to be looking straight into you. It was the kind of photo that simultaneously intrigues and repels. The blank stare of the unseeing.

Looking at that picture, I thought how you cannot see your reflection in a dead person’s eyes. But not many people could see that picture of Bundy, or any dead person, without seeing themselves. That is why the picture was so hard to look at.

I thought there was more that I was meant to see in Bundy’s picture. I thought I was supposed to understand that there would always be terror in the world, that you cannot get rid of terror any more than you can get rid of good. That even if you tried to get rid of terror, it would always be there, staring you in the face.

I get into my bed and think that maybe I am living in a shadow, a shadow cast by Bundy’s death, and it grows deeper and wider with each birthday.

I don’t blame my doctor for anything. She did what she had to do. There are cases of women having hysterectomies who really do not need them. This was not the case with me.

When the doors of the operating room opened, I thought the room looked like a garage. Like an oil-change place or like an old garage I went to once with my father when I was little. I didn’t have my glasses on in the operating room, so I really cannot say for sure how everything looked. But the room felt empty, the way places feel empty when people come and go and sometimes die there, but nobody actually lives there.

My doctor held my hand before I went to sleep. It felt like a sweet invitation, the way she held my hand.