When I was thirteen, a rumor swept through my school that a flying saucer had been seen hovering over the river and then zipping away at an impossibly high speed. We had grown up on weekly doses of The Twilight Zone and Star Trek, so it didn’t seem impossible that alien beings were visiting our small Midwestern town. I, for one, was thrilled by the possibility.

The next day at school some other girls and I congregated in the restroom off the cafeteria. Cassie said her older sister had received a telepathic message from the aliens: at exactly 2:46 PM that coming Friday, the UFO would appear on the front lawn of the school. I was ecstatic.

That night I heard my mother gossiping on the phone about Cassie’s family. There was a rumor of divorce, which to me sounded more impossible than beings from another planet visiting my school.

The next day, Wednesday, Cassie had more news from her sister. “They’re looking for girls,” she said. “They want thirteen-year-old girls to take back to their old, dried-up planet.”

“I’ll go,” I said.

“Me too,” said Cassie, her eyes severe behind horn-rimmed glasses.

The rest of the day girls discussed the pros and cons of volunteering to populate a faraway world on the verge of extinction. We passed notes in the hallways and whispered in classes.

On Thursday Cassie told us more: the aliens wanted only girls with glasses, because that meant they liked to read and would have smarter children. Both Cassie and I wore glasses, but most of the others didn’t. Was there time for them to get glasses before the next day at 2:46? Not likely.

On Friday morning my hands shook with anticipation. I packed a toothbrush and a camera in my book bag, just in case. All day long I watched the clock in a kind of hypnotic daze. Cassie showed me the angry farewell notes she was leaving for each of her parents.

When the big clock in the front of the classroom read exactly 2:46, all heads turned to the windows overlooking the front lawn. A truck drove by. A crow cawed.

There was a collective sigh and a few giggles. Then I heard the sound of raw sobbing from the back of the room. I didn’t have to turn in my seat to know it was Cassie.

Merina Canyon

Ashland, Oregon

In college I lived in a slightly chaotic housing co-op where my housemates and I — male and female alike — thought nothing of snuggling up together to watch a movie or putting our arms around each other as we walked down the street.

After graduation I decided to spend a season volunteering for a world-hunger organization on its “educational ranch.” I’d recently broken up with my boyfriend and wanted only platonic relationships for a while. The first friend I made was Shawn, who had been working on the ranch for a few years. I felt comfortable with him because he was engaged, which made him off-limits romantically. His fiancée lived about an hour away.

Shawn and I started spending a lot of time together, listening to music and going on walks. I often hugged him the way I had my friends at the co-op, without any romantic intent. A few weeks into my stay at the ranch, one of Shawn’s friends pulled me aside and said that Shawn’s fiancée had heard how close the two of us were, and she wasn’t happy.

I was shocked. I wasn’t the sort of person to break up relationships. The next day I told Shawn that we needed to stop spending so much time together.

It was too late. Within a week Shawn and his fiancée had broken off their engagement. He told me their relationship had been rocky for a while, but people seemed to take it for granted that they’d split because of me. The rumors were so vicious that I started to believe them myself: maybe I had been trying to break them up. I continued spending time with Shawn even as he tried to patch things up with his ex.

A few days before I left the ranch, Shawn and I slept together, the engagement ring on the table beside the bed. It was awkward and lacked passion, and I regretted it. I had allowed the rumors to turn me into the sort of person I’d believed I wasn’t.

Name Withheld

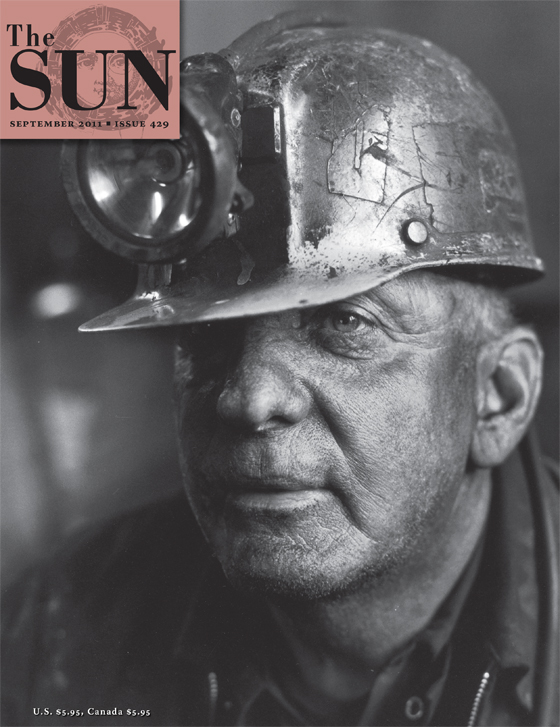

At the age of sixty-five I was convicted of a felony and went from being a devoted husband, father, and grandfather to being a prison inmate. My first stop on the way to the federal penitentiary was a county lockup, where I shared a cell with a career criminal.

“How long are you down for?” he asked.

“Seven and a half years.”

“You’ll do four and a half,” he said with an air of certainty.

“But my lawyer told me you have to serve at least 85 percent of any federal sentence.”

“Not anymore. Congress just passed the 65 percent law. Obama has already said he will sign it.”

My heart soared. Only four and a half years away from my family! I couldn’t wait to get to a telephone and call my lawyer.

When I finally did, I was brought up short. Talk of the 65 percent law had been around since he was in law school, he said. It was an old jailhouse rumor.

I have since heard many such tales of drastically reduced sentences. For a time I wondered how anyone could be cruel enough to float such a rumor. Now I have a theory, summed up in a single word: hope.

Is it truly an act of cruelty to create, for a brief moment, the illusion of hope where none exists?

Steve Marshall

Oakdale, Louisiana

I was shy in high school, especially around boys, and had dated just twice by the time I reached my senior year. Then I met Frank. He sat behind me in English class, sticking his feet under my desk and kicking mine as I tried to write. Every day he’d come into class with some joke or story to make me laugh.

He asked me to go to a school play with him, and I said yes. I enjoyed being around him and his many friends. We went out a few more times, and Frank started carrying my books to class and talking with me in the hall until the last second before the bell. I felt so happy I began to wonder if we could have a future together.

When a girl asked if Frank and I were going steady, I smiled and said, “Pretty much.”

“Is Frank still planning on becoming a priest?” she asked hesitantly.

I was shocked. Had he just been stringing me along, making a fool of me in front of the other kids?

On our next date I kept mostly silent all through dinner and the movie afterward. When Frank asked if something was wrong, I blurted out what I’d heard about him, hoping he’d say it wasn’t so. He looked down and told me that he’d be leaving for seminary in the fall.

And I had been thinking we might have a future together! I asked why he hadn’t told me sooner, why I’d had to hear it from someone else. He apologized and said that since meeting me, he had been having doubts about his vocation. But he did go to the seminary that fall.

I dated many other boys after Frank, but I never forgot him. When he dropped out of the seminary, I decided to give him another chance.

We’ve been married for forty-two years.

Kelley R. Chikos

Vernon Hills, Illinois

Growing up in wartime Germany, my brother and I were told never to pass on rumors or to repeat outside of our home anything that was said inside of it. My parents were against Hitler’s regime. They had lived overseas for many years and were more open-minded than most German citizens, who knew only Nazi propaganda.

To escape the air raids in the city, my mother took us to her sister’s country estate, an idyllic place surrounded by lakes and forests. One day our aunt Dora told our mother about some neighbors who’d been arrested. The neighbors’ daughter had shared with someone that her parents did not agree with Hitler, and the whole family had been taken to jail. Dora kept on repeating the rumor, as if amazed that she lived so close to such traitors.

That night our mother packed our things, and we left the next morning. Years later I learned that Dora’s husband had been a high-ranking official in Hitler’s Gestapo. One careless word from my brother or me in her house could have cost all of us our lives.

Anneliese Carber

Dallas, Texas

The rumor was that the computers were all going to break down. The programmers hadn’t thought ahead, and, at the dawning of the twenty-first century, everything in our wired world was going to slam to a halt: no money from the ATMs, no gas from the pumps, no groceries from the store. They even had a catchy name for it: the “Y2K bug.”

I had read plenty of science fiction as a teen, so it seemed plausible to me that a small mistake could bring humanity to its knees. And, as a young father, I had a duty to protect my wife and sons. So I made lunchtime trips to the warehouse club for cases of dry soup, pinto beans, flour, and rice, and I spent Saturdays sealing everything into airtight five-gallon buckets. For weeks every drive home from work included filling a ratty gas can, which I later emptied into a barrel in the driveway. I bought a generator and a handgun and huddled with a like-minded conspiracy theorist at work to discuss the latest predictions: food riots in the cities, worthless currency, survival of the fittest.

Hunkered down in a mountain cabin on New Year’s Eve 1999, surrounded by pinto beans and hollow-point ammunition, I found myself actually hoping the rumors were true, that we would awaken on January 1 to a silent and still world. Perhaps we would use this occasion to rethink how we lived and (after the panic and riots) unite in a vision of a more sustainable life.

I was almost disappointed when nothing happened.

Steffen Smith

Blue Ridge, Georgia

I don’t know why I stayed to play strip poker. My other friends had scattered when Rick, who was fourteen, suggested it. I was eleven and had seen the sex-ed movie at school, so I was curious.

It was just Rick, his sister Joanne (who was my age), and I. We locked ourselves in the downstairs bathroom at their house, and Rick dealt the cards. Piece by piece we shed our clothes. Then Rick and Joanne showed me another game: Joanne lay naked in the bathtub, face up, and he lay on top of her, face down. He asked if I wanted to try it. I did. He put his naked body on mine, but that was it, no intercourse. Still, I knew we had crossed the line. I scrambled out of the tub, threw on my clothes, and ran home.

I was certain that, as soon as I started menstruating, I would become pregnant. (The sex-ed movie had left some parts out.) For weeks I woke every night with severe stomach pains. My parents took me to see the pediatrician. I was terrified that he would somehow be able to tell what I’d done.

Finally I decided that if I could make Joanne look bad, I wouldn’t feel so bad myself. So I started to tell people about what Joanne and her brother had done in the bathtub. I didn’t mention the fact that I’d done it too.

Joanne’s family eventually moved out of the neighborhood. For all I know, she went on being abused by her brother. I wish that, instead of spreading rumors, I’d tried to help her.

A.M.

Hartford, Connecticut

When I was a freshman at a small college in the early eighties, a rumor circulated that two girls had been seen kissing late one night outside the dormitory. There were no openly gay students on campus, so everyone was trying to figure out who they were. I didn’t care. I was in love with Billy, a short, stocky boy with acne who loved to get drunk and listen to Adam Ant. I drank too much, too, and sometimes when I was trashed, I’d lose control of my emotions. I constantly questioned Billy’s motives in our relationship. Was it love he wanted or just convenient sex?

The next year I was stumbling down the dorm hall after a night of partying when I saw a girl named Deb sitting on the floor outside her room. She and her roommate, Belinda, were best friends and kept mostly to themselves. But that night Belinda wasn’t around, and Deb looked as if she’d been crying and drinking. She was watching ants move along the floor, which was littered with saltines that had gotten stepped on.

I plopped down next to her and asked what was wrong. Maybe because we were both drunk, or maybe because she was tired of hiding, she confided that she and Belinda had been secret lovers since high school, but now Belinda wanted out. As she talked, I leaned against the cold wall and watched the ants carry away the cracker crumbs, thinking how vulnerable love makes us all.

Name Withheld

In July 1971, just short of his sixty-ninth birthday, my father had a massive heart attack and died. His death was not unexpected — he’d had rheumatic fever as a child, and it had damaged his heart — but my mother was devastated. She and my father had been married for forty years.

At the wake my mother rarely stopped sobbing. Then a woman I had never seen before came up to her and said they’d gone to nursing school together forty years earlier.

My mother remembered the woman and introduced her to me as Claire.

“He looks so much like his father,” Claire said, wringing her hands. Then she asked to speak to my mother alone, and they retreated to an empty corner of the room. I watched as Claire talked and my mother listened. Claire seemed to be apologizing. Then she embraced my mother and left. When my mom came back, I asked what Claire had needed to talk to her about.

“She had a story to tell me” was all Mom said. I felt it wasn’t the time to ask for an explanation.

A month later I was helping Mom clean out her attic when we came across a picture of her nursing-school graduating class, circa 1930. I picked her out of the crowd, and she told me the pretty girl beside her was Claire. “We were best friends back then,” she said.

“What did she say to you at the funeral?” I asked.

Mom had told me before how she’d met my father, a medical intern, while she was in nursing school, and within a year he’d asked her to marry him. But now she added a new twist to the story: Before they announced their engagement, Mom’s uncle fell terribly ill and needed in-home nursing care for the summer. So my mother arranged for a temporary leave, bade a teary goodbye to my dad, and left the next day.

“There was no telephone at my aunt and uncle’s home,” she said, “so I wrote to your father the day after I arrived, telling him I was safe and giving him my address. But the way mail was in those days, he didn’t receive my letter until well into the following week.” When she got an answer back from him, almost three weeks after she’d left, it said how overjoyed he was to hear that she was well. There’d been a rumor around the hospital that her bus had crashed and she’d been killed.

“We never knew how that rumor got started,” she said, “and by the time I returned the following fall, we had practically forgotten about it.”

The mystery wasn’t solved until the funeral: Claire had started the rumor. She’d been in love with my father and had thought that, if my mother was out of his life, she might have a chance.

Nick Ingoglia

North Caldwell, New Jersey

I was quite miserable in high school, and my mom and dad didn’t help matters much. They were older than my classmates’ parents and did not participate in my academic life other than to give me rides to and from school in one of our ridiculously outdated cars. Instead of socializing, my weird parents stayed at home and read books, played the piano and organ, and generally formed a great barrier to my efforts to blend in.

When my best friend (to be honest, my only friend) became heavily involved with Job’s Daughters, a Masonic youth group, my father warned me against joining, but I desperately wanted to follow my friend into this strange new world of ritual and secrecy. I swore to my parents that I’d pay all the expenses, wouldn’t let my schoolwork suffer, and would never ask for anything else in my entire life. I think they gave in from sheer exhaustion.

My fellow Daughters of Job viewed me as an enigma who had circumvented the usual paths to entry. My parents certainly did not come to the planning meetings or contribute to the pancake-breakfast fund. At family events I stood out like a blemish. So I tried even harder to fit in. I joined the drill team, marched as if it were my job, memorized volumes of secret texts, and sang militaristic hymns with great feeling.

That year our drill team won all the local competitions and made it to the state championship. We took a bus to Chicago, stayed in a fine hotel, competed furiously, and won. When we returned to our small hometown, newspaper reporters and photographers were there along with a crowd of locals to applaud our achievement. My parents were nowhere to be seen. I had to catch a ride with a friend’s mom.

When I got home, I rushed into our house and told Mama and Papa about our exciting win.

“That’s nice, dear,” my father said. “Please take the dog out.”

On Monday I was called into the vice-principal’s office. I knew Mr. Tate was a high-profile Mason, so I thought his request must have had to do with the drill team’s success. I was wrong.

“We know what you did,” he began.

My face grew hot, and I struggled to remember anything I might have said or done wrong. Drawing a blank, I asked what he meant.

Mr. Tate straightened up in his chair and cleared his throat. “I think you know.”

I shook my head and began to cry. “I don’t!”

Mr. Tate said I’d been seen going to the boys’ floor in the hotel, despite strict rules that girls were never to enter a boy’s room. “We know you were there, and it won’t do you any good to deny it,” he said. “Go back to class, and we will take this up on Wednesday before the council meeting.”

I went to the restroom, where I hid in a stall until the bell rang and the halls cleared. Then I called home from the pay phone in the courtyard and asked my father to come and get me.

When he rolled up in our huge old car, I threw myself in, hunkered down on the bench seat, and told him everything.

My father, who always drove with both hands on the wheel, briefly took one hand off and laid it on my shoulder. “There are three types of people in this world,” he said. “Some people talk about books. An elite few speak of ideas. But most people talk about other people. You have just experienced the daily fodder of shallow minds.”

Name Withheld

My grandmother did not like sex. I am not sure if my grandfather knew this before they got married in the 1940s, but he certainly knew it after. He had many affairs throughout his married life — at least, that’s what I’ve assumed after finding his album overstuffed with photos of beautiful black women wearing lace-trimmed, silky dresses and smiling at the camera.

According to my cousin he tried to make the marriage work, but his wife barely let him touch her or even see her naked. He eventually moved into the basement and ceded the upstairs to her.

When he was in his sixties, my grandfather hanged himself. My grandmother found him dangling in the living room.

When my father pried open the locked wooden toolbox in the basement, he found reels of film inside: my grandfather’s collection of pornography.

Twenty years after his death, his basement still hasn’t been fully cleaned out. The bar he built is there, covered with dust, and so is the long white sink where he developed his black-and-white prints. His carpentry tools and old spare parts lie strewn about.

I hear whispered stories about this man I barely knew or saw while he was alive: That he trained in a gym frequented by Joe Louis. That he was afraid of flying, which was why he visited us in Ohio only once. That he kept my sister’s and my Social Security numbers in a small, frayed notebook he carried in his pocket and used them to buy government bonds in our names. That he took so many pictures of my mother as a child that my grandmother feared their daughter would go blind. That he had another daughter with a woman from the town where his brothers and sisters lived. That his siblings embraced that child and her mother as their own, even as my grandfather denied responsibility. That he possessed an open face, eager brown eyes, and a throaty laugh.

I wish I could know more about my grandfather. These rumors are not much to go on, but in my family — where we survive on silence and denial — they are a start.

B. July

Washington, D.C.

At the age of fifteen, sitting alone in the high-school gymnasium for the “welcome freshmen” assembly, I overhear someone I don’t know telling someone else that I am gay. I spend the rest of my high-school years trying to quash that rumor and fit in.

Even in college I make sure not to be too creative or stand out in the crowd. I work my way through grad school and succeed in staying too busy for anyone to get to know me.

At thirty I begin to have relationships, but they fail because I have no idea who I really am. So I decide to find out. With the help of friends, family, therapy, and God, I start to peel away the layers of my identity. After a year I get a glimpse of the real me and feel truly happy for the first time.

I’m now thirty-four and ready to share the real me with someone else. But first I’m going to contact the guy who spread the rumor about me in high school. Here is the message I have ready to send him online:

“Remember that rumor you started in high school about me being gay? Please start that rumor again. I’m a few years behind in my love life and could use some help getting the word out.”

Nicholas David Sanchez

San Francisco, California

In seventh grade Patty hung with the popular crowd, but she wasn’t particularly friendly. In fact, she was prone to playing mean pranks and flaunting her family’s money whenever she could. She lived in a huge house and had a closet full of designer clothes.

One morning at school there were frantic whispers that Patty had gone to the emergency room the night before. She had tried to stick a hot dog “up there,” and it had gotten stuck and had to be surgically removed.

It was the perfect rumor: titillating, disgusting, sexual, and about a girl whom no one especially liked. We were insatiable for more details, and there was always someone who would oblige: Patty’s screams when it wouldn’t come out, her mother’s attempts to remove it, what the doctors finally had to do.

Patty transferred to a different school, but the rumor never died. When she came back to visit years later, someone dared a new boy to ask her if she’d like a hot dog while everyone sniggered.

Twenty-five years later, if you ask anyone in my graduating class what “hot dog” means to them, her name will come up.

Laura Amann

Elmhurst, Illinois

Our parents fined my siblings and me for using hurtful words. We had to put a dime in a jar anytime we called each other a liar or a fool, for saying, “shut up,” and for disrespecting one another. The worst offense — repeating a rumor — cost a quarter, which was a whole week’s allowance.

Once, after I related to my mother some intimate information my best friend had told me about her family, Mama demanded a quarter for the jar. When I argued that what I had told her was a fact, not a rumor, she said it made no difference whether it was true or not; anything that might cause embarrassment or hurt feelings should never be repeated, not even to her.

The summer I was thirteen, a deranged teenager shot and killed my daddy, leaving Mama alone to raise seven children between the ages of one and sixteen. As the oldest girl, I became Mama’s confidante. She told me that my sixteen-year-old brother had been conceived with her first husband, an abusive alcoholic, but she’d soon left him and gotten the marriage annulled. A few years later she’d met Daddy, who’d married her, adopted her three-year-old son, and set out to raise him as his own. She said my brother had always known the truth, and she had told only her closest friend, so she was sure no one else in town knew.

On the first day of school that fall, I was still reeling from the loss of my father, my mother’s revelations, and my new responsibilities. I fought back tears in carpool, thinking how I would never again turn to see my father blow me a kiss. The mother who was driving that morning asked how my family was doing. I said that we were OK, adding that my older brother was taking it the hardest and had broken down sobbing at breakfast that morning.

“Well, that’s surprising,” the woman said, “since I understand he wasn’t your father’s real son.”

Determined not to cry, I muttered under my breath, “You owe me a quarter.”

Faye Christie

Atlanta, Georgia

At forty-four I finally met the man of my dreams: an author, a brilliant teacher, and an accomplished athlete. He was tall and handsome and, most important, kind. He swept me off my feet just as I was embarking on a business trip to Asia. He said he could wait a few months until I returned.

I wrote to a girlfriend to share the good news. She knew the man and said he seemed like a womanizer. Another friend who knew him wrote, “Great guy, but I’m not so sure about his relationships with women.”

I was prepared for these rumors. He had told me about his ex’s attempts to sabotage his reputation after their breakup. This man was a pillar of our religious community. There was no way he was a liar.

While I was in Asia, he invited me to spend a weekend with him in Nepal, where he did charity work with impoverished children. Later, after he’d returned to the States, I sacrificed the majority of my year’s salary to fly home early from Asia and spend the winter skiing with him. We laughed in the snow, sipped wine by the fire, and made love every morning. He asked me to return to spend the summer with him.

“I’ll take care of you,” he said.

In the spring I reluctantly went back to Asia to complete my work, and we wrote every day.

A few days before I was to return, I received an unusual message from him. He was extremely busy preparing for a huge conference he was to lead, he said. Could I delay my return by two more weeks? “It will be too distracting to have you around,” he wrote, “because when you are here, I want to devote all my attention to you.”

I good-naturedly agreed and decided to visit my family first.

The evening I landed in the U.S., he dumped me. By e-mail. No reason given.

I suddenly had no place to live and no jobs lined up for the summer. Feeling blindsided, I called him.

“Is there someone else?” I asked.

“I’ve just pulled back, that’s all,” he replied coldly.

A friend of mine ended up being his assistant at the conference. Afterward she told me all about his new girlfriend.

Name Withheld

At fourteen I was the oldest camper at Girl Scout horseback-riding camp and the only one who had been to the camp before. A quiet, awkward kid, I was used to being picked on, but at camp, for the first time in my life, other girls looked up to me.

Early in the week I caught a glimpse of our counselor’s clipboard and saw the notation “w-child” next to one girl’s name. I read a lot of trashy romance novels and assumed this meant she was “with child.” Wanting to show off my worldly knowledge to the other girls, I shared what I’d discovered. The rumor quickly spread, and we divided into two groups: most of the girls were on my side and believed the rumor, but two girls stuck with the supposedly pregnant camper.

I was amazed that the majority followed me, but I was also starting to rethink my original assumption. We had all had physical exams before camp, and I was certain they would not let a pregnant girl go horseback riding. I decided that maybe the notation meant the girl was a “wild child,” and I told the other girls this, but it was too late.

When our parents came to watch us ride, I overheard the girl who was the target of the rumor sobbing while I was grooming my horse. I wanted to go and apologize, but I just stood there and listened to her cry. It was the first time I realized what power my own words had.

Beatrice Underwood-Sweet

Winchester, Kentucky

The rumors started because of my red patent-leather shoes with the stacked wooden heels and gold buckles on each toe that looked like the buckles on pilgrims’ or witches’ hats. Even balanced with more subdued, professional clothing, those sexy, bold, confident shoes made me look a little more daring, a little more colorful than my co-workers.

It was my first professional job right out of college, so of course I made mistakes. Some were trivial and easily corrected with a letter or a change to a document. Other mistakes were bigger, like the relationship with my married boss — whispering with him behind closed doors, sneaking out to lunch, making him blush with my outrageous texts in the middle of dry business presentations.

It wasn’t long before the rumors flew thick and fast around me. I learned of them through my few friends in the office. I never heard anything about the boss and me, though. It was always about the little mistakes I’d made, or my shoes. Somehow those risqué shoes were more than my conservative co-workers could tolerate.

Soon fliers were posted by the time clocks, reminding everyone about the dress code and appropriate footwear. But I had already scoured the dress code and knew that my shoes were in compliance. I received notice that I was “on the radar” with corporate for my shoes. I was taken aside by the human-resources representative, who didn’t quite know why she had been asked to talk to me. She said she felt sympathy for me and was actually relieved not to be the target of the office gossip for a while.

Finally there was an all-staff meeting to remind everyone that high heels were not appropriate footwear. But I’d be damned if I was going to bend my personal style to appease a bunch of middle-class middle managers. I continued to wear the most flamboyant shoes I could find: leopard-print stilettos, high wedges, purple suede heels. I resented being singled out for such a petty reason, when no one could find much fault with my job performance and no one dared speculate out loud about what I might be doing with the boss.

Finally I found another job and gave my two weeks’ notice. On my last day I contemplated wearing the most vertiginous heels in my closet, but now that I was leaving, I no longer wanted to bait the office gossips. I actually felt compassion for them, working in an environment that felt so treacherous, even for longtime employees. I decided to go out with class: just a simple black pump.

It would be a long time before I could admit to myself that the rumors had had nothing to do with my shoes.

Name Withheld

I once spent a summer working in a corrugated-cardboard factory. I was a junior in college and saving up to study abroad in my senior year. The cardboard business was going strong, which meant fifty-hour workweeks and punching in at 5 AM.

After the first week I got promoted to the gluing machine, where I would work next to Larry. He had come to the factory straight out of high school eighteen years earlier and didn’t waste a minute telling me what he thought about everyone.

“Look at that asshole,” he said, pointing to the floor manager. “Just between you and me,” he said, leaning in even though we were wearing orange earplugs and yelling, “I busted in on him giving that Asian guy a blow job.” Then he smiled and waved at the distant floor manager.

Sure, Larry’s gossip was mean-spirited, but I had to laugh. I was the son of a gentle, ethical physician. For all my nineteen years I’d been told to be polite and not spread rumors. This was my first exposure to mean, dirty trash talk.

“Here comes that little yellow-ass bastard now,” Larry said, smiling unctuously as our Asian American co-worker strode up to the gluing machine. I felt terrible for laughing, but I did. Larry’s acerbic tone made everything seem funny. After he left, I asked Larry, “Are you sure about that guy?”

“Oh, yeah,” said Larry, nodding. “Just look at him. I heard he even swiped Dave’s hammer yesterday at lunch.”

While we worked, Larry and I chatted about topics that my dad wouldn’t touch, like how much “pussy” I was getting in college and how often I got wasted. We talked about Larry’s four “bastard” kids and the “whore” who was raising them.

One day a forklift pulled up and set a giant pallet of boxes right in front of the ladder on Larry’s side of the gluing machine, blocking his escape. The driver grabbed his box cutter and got about six inches from Larry’s face. “I heard what you said about my wife,” the man said, rolling the box cutter angrily around in his hand. I backed as far away as I could on the little platform.

“Jesus, what are you talking about?” Larry said in disbelief. “Your wife is awesome, man! If I could get a piece of ass like that, I’d sell my truck!” Larry was smiling but nervous.

The man squinted. “I don’t believe you for a second, Larry,” he said, “and if I ever find out that what you said is true, I’m coming back.”

Larry kept smiling as the man left. I stared wide-eyed at Larry. “What are you looking at?” Larry said. “Just because I gave it to his dirty whore wife in the ass doesn’t mean nothing.” I laughed despite myself.

Toward the end of August I was moved to a new machine, where I worked with Dave. I extended my hand across the conveyor belt to him, but he just let it hang there. After about twenty minutes of silence Dave finally spoke. “So you’re the lazy-ass faggot that stole my hammer, huh?”

I furrowed my brow. “What are you talking about?”

He grimaced and spat tobacco on the floor. “Larry told me all about you.”

Ty Sassaman

Minneapolis, Minnesota

At first it’s just a rumor. The legislature is going after public-sector pensions next, a friend says. But I don’t want to get involved, don’t want to organize. It’s hard enough teaching English to city high-school kids every day. Besides, there have been so many rumors: another 10 percent to be cut from school budgets; teacher layoffs across the city; public schools closed to make way for charters; newer teachers to be denied due-process rights. Surely they can’t all be true.

Then it appears on The New York Times website: “State Bankruptcy Option Is Sought, Quietly.” This would permit the state to “alter its contractual promises to retirees” — i.e., default on pensions. I’ve come to teaching late and will need every penny of the small pension I’ve accrued. Still, I’m turned off by the idea of activism. Haven’t I earned the right to use my spare minutes to write poems?

Days later Phyllis, a bright, dedicated science teacher who has helped revitalize her department, is informed that her tenure application has been flagged for vague reasons, and if she pursues tenure, she faces dismissal. A bureaucratic middleman comes to our school to get Phyllis to sign a document prolonging her probation period. Phyllis refuses.

“They’ll never find a better science teacher than Phyllis,” I nearly shout, talking alone with our union rep. I stay up late composing a letter that every tenured teacher has agreed to sign. I’m surprised how many colleagues have been pushed to the edge of their patience.

On the day of Phyllis’s deadline, the news is full of stories about angry public-sector workers occupying Wisconsin’s statehouse. But I can’t find Phyllis. From a stairwell I call the union rep, who’s home sick. She can’t talk; she’s on the phone with Phyllis.

Finally I hear that, under threat of dismissal and with an infant child to support, Phyllis has decided to capitulate. The union rep explains that if a principal puts forward a tenure application that’s been flagged, district superintendents have been encouraged to treat it as an act of insubordination and fire the principal. Like Phyllis, our principal lacks due-process protection and can be dismissed without a hearing.

The battle is lost, but nothing is as it was a day ago. Solidarity has emerged within a once-divided staff. And something has changed in me. Who can tell if Wisconsin workers will retain their right to organize, or what will become of our school? Rumors continue to fly. Meanwhile I must find Phyllis and offer whatever comfort the now-moot letter of support can bring.

Name Withheld

By the time I was a sophomore in high school, my parents regularly threatened to do any of three things: kick me out, put me in a foster home, or lock me in the local teen mental institution, St. Anne’s Green. It’s not that I was a juvenile delinquent; far from it. I was a driven overachiever, in all honors classes. I didn’t smoke, drink, or do drugs. I’d never so much as kissed a boy — I had no opportunity, since boys categorically shunned me for my obesity, nerdiness, and lack of femininity. I was the daughter that most parents would be relieved to have, but somehow mine saw in me only mistakes and failures. Our vicious, volatile arguments left me sobbing. I thought about suicide.

One morning my mother told me she’d scheduled a doctor’s appointment for me during the school day, and I’d have to miss classes. I’d never missed school for an appointment, but I’d just gotten contact lenses and figured maybe the optometrist had a busy schedule — until my mother drove up to St. Anne’s Green, where my therapist was waiting for us. He and my mom insisted that I check myself into the psychiatric hospital for six months. I was told that if I didn’t voluntarily commit myself, they’d have me forcibly committed to the state institution, far away, where the mandatory stay was a year. I cried until I almost passed out, but I was powerless.

I had just gotten cast in the school musical. I had English assignments, geometry, baby-sitting jobs, synagogue youth group, a whole life I’d had no idea I’d be wrenched away from. And since I hadn’t known I’d suddenly be locked up, I had no way of telling anyone what had happened to me — not that I wanted to.

When I finally earned a weekend visit home, my friend Jean had me over to her house. She and my friend Sarah tried to fill me in on what I’d been missing as we painted our nails on the bed.

“Well,” Jean started, “you should probably know there are some rumors about why you’re not at school.”

“Oh,” I said, focused on the bedspread.

“Yeah,” said Sarah, “some people said that you had lice and got sent away because you’re so contagious.”

“Lice?”

“And some kids think that you’re dying of cancer,” Jean added.

“I guess that’s better than lice,” I said.

“But the main rumor,” Sarah continued, “is that you got pregnant and are in a home for unwed mothers until you have the baby and give it up for adoption.”

I looked up. “Kids think I’m pregnant? Oh. My. God!”

If my classmates believed I was pregnant, that meant they believed I — the fat, ugly, dateless dork — had had sex. Which meant they believed I was worthy of sexual attention — from a boy. I felt like I had just been endowed with an entirely new identity far more desirable than the truth.

“Oh, my God.” I started laughing. “Please keep that rumor going! I’m pregnant! I’m a pregnant teen!”

Jean and Sarah laughed with me, and I remember that moment of joy, at being so bizarrely and ironically mislabeled, as one of the only bright spots in what were possibly the worst six months of my life.

Name Withheld