In the six months I lived in Las Vegas, three bicycles were stolen from me, my cook’s tools were stolen, and a woman was murdered in front of my apartment complex. I wanted to find out who the woman was, but there was no mention of her in the newspaper. So I called the Journal and asked a reporter named Matt about the murder. He said he didn’t know the details and admitted that his paper had an unwritten policy not to cover all the murders and suicides that happened in Las Vegas, because it might discourage tourism.

I’d come to Las Vegas to dry out, to cook for a casino, to gamble, and to write a novel. The gambling part had turned out well, but the viciousness, shallowness, and vulgarity of the city had worn me down. I was hankering to go someplace peaceful and friendly and slow. And I was secretly, as always, praying for a metamorphosis from unpublished writer to respected author.

It was January 1991, and, reluctant to travel in winter, I lingered in that lonesome, overdecorated desert town, gazing down at the pool from the window of my furnished apartment on Sahara Avenue, reading books and taking notes, napping, watching movies on the TV chained to the wall, typing in my tiny kitchen, walking streets that echoed with ringing jackpot bells, and wondering where I would go next. My question was answered when my old friend Oscar Roman, whom I’d met years earlier when we’d cooked together at the Broadmoor Hotel in Colorado Springs, called and asked if I wanted to come work at his new restaurant in Middlebury, Vermont. Small-town Vermont sounded like the farthest I could get from Las Vegas. “Sign me up,” I said.

Since I had some money for a change (thanks to my gambling success), I flew to Burlington, where Oscar picked me up at the airport. I hadn’t seen him in four years. He was my age, thirty-six, a diffident, tense, hardworking man with hair down to his collar and a delightfully absurd sense of humor. Oscar had recently gone into considerable debt to get a degree from a well-known culinary school, then further immersed himself in red ink with the purchase of a picturesque restaurant he called Oscar’s Cafe.

It was eleven at night by the time we got to Middlebury. Oscar gave me a tour of his restaurant, a low-ceilinged space with blond curve-backed chairs, crosscut oak tables, a cozy, six-stool bar, and large windows overlooking Otter Creek. Past the bar, through the swinging doors, was the kitchen, with its array of gleaming kettles and hanging pans, a pot of demi-glace simmering on the range. He opened refrigerators to show me local produce and lamb, buckets of live mussels and clams, packets of fresh herbs from the farmers’ market, and the crème brûlées and court bouillon he’d made that day. He said he had the best wine list in the county. We sat for an hour in his dim dining room, looking out the big windows at the glistening frozen creek, drinking his wine, and discussing the menu and my role in his establishment. The pressure on him to make the business work was palpable.

Over the next few days I put down first and last month’s rent on a small but recently refurbished apartment, saw a dentist for the first time in twelve years, and bought a Random House Encyclopedia on sale at the downtown bookstore. I immediately began to study the giant volume so that I might at last know what people were talking about when they mentioned Charlemagne or the Eighty Years’ War. I was steeped in the innocent conviction that, although none of the dozens of other places I’d lived had brought about that prayed-for literary transformation, Middlebury was the metamorphic cauldron from which I would finally emerge a mature, accomplished writer. As if to encourage this belief, my encyclopedia informed me, in a chapter titled “Threshold of the Vertebrates,” that complete metamorphosis involves a change in habit or environment. Of particular interest to me was the theoretical process known as “neoteny,” whereby some creatures skip stages of development and go straight from larval stage to maturity. In my experience this appeared to occur with the majority of famous writers: one minute they were living at home with their parents, and the next they had leaped directly onto the pages of The New Yorker.

In the interim I learned the routine at Oscar’s Cafe. I was the pantry man, in charge of salads and torching brûlée and sautéing various side dishes, along with washing pots and tending bar during the occasional rush. Business was slow, but Oscar refused to advertise or put coupons in the local paper or hire a clown to stand out front with a sign. Good service and great food, he believed, were the sole ingredients necessary for success. Later he would admit to the existence of other crucial factors, such as location, demographics, and luck.

There were a few regular customers — a trickle of gourmands, a handful of professors from the local college — and the occasional looky-loo who’d zigzag down the icy hill, grumble at the prices on the menu, and then fishtail back up the grade to get meatloaf, mashed potatoes, and frozen peas from the local diner. There was also the Romance Writer, who, after a hard day of churning out soft porn, spent the majority of his afternoons and evenings at Oscar’s bar. Though the Romance Writer wrote formulaic paperbacks under a female pseudonym, he looked the way I imagined a real writer did: barrel-chested, gray-haired, relaxed, always with an attractive woman at his side. I was envious of his leisure and his alluring feminine companionship. I longed to talk shop with him, perhaps commiserate about writer’s block or pry from him a few secrets of the trade.

One day I mustered the courage to tell him I was a writer.

“Oh, what have you published?” he asked.

“Nothing — yet,” I replied and then babbled a bit about the novel I was working on and the encouraging reply I’d received from a small magazine in the Midwest — I couldn’t remember its name, but it had published an early story by Saul Bellow. I mentioned the sea squirt’s place in the chordate line as it pertained to the zoological concept of neoteny, which I’d read about the night before in my encyclopedia and which seemed to me somehow related.

He nodded, looking as if he hoped I might go away.

Cheeks and ears burning, I muttered something about needing to get back to work and stumbled off.

One snowy February night I was strolling home from the cafe, stewing about my asinine confession to the Romance Writer, lamenting the three rejection slips that had been forwarded to me from Vegas, and feeling the cauldron of my metamorphosis cooling like a big pot of chicken noodle soup when I heard an unholy bellowing up ahead. Alone on the street in the shuttered downtown, I stopped to listen. Someone was letting loose a stream of vile curses — but at what, or whom? The awful yowling drew nearer until its source emerged from the darkness: a tall, cleanshaven man in his twenties dressed in a long overcoat, knit cap, and gloves. He thrust out his chest at me and said, “What the fuck are you looking at?”

Having grown up a weak, asthmatic, violin-playing boy who was regularly beaten up by the neighborhood children, I was thin-skinned about being bullied. I was also strong now from manual labor and lifting weights, and aware from years of living in tough neighborhoods that passivity was no defense when you were accosted alone at night. All of which is to explain why I answered his question by taking a wild swing at his head.

The stranger seemed pleased by my response and began hopping around, fists raised in the classic Queensberry pose. “Get down on your knees and suck my dick,” he ordered.

I dropped the book I was carrying and whistled another one past him as he moved in with a failed counterpunch. “What do you think you are,” he said slyly, “some kind of ninja warrior?”

Mouth dry and hands shaking, I continued to come at him, but he backed away through the snowy street and into the park. The more I pursued him, the more animated he got.

“We’ll settle it right here,” he declared, feinting and lunging and bobbing out of my reach, even when I wasn’t trying to hit him. By now I’d realized that the young man was disturbed and had no gift for society other than his opposition to it. Having lost interest in fighting him, I pushed him to the ground, told him to get back to the mental hospital, and walked away.

He sprang up and followed me. The “fight” meandered back into the icy street, where neither of us could get decent footing. When he tried to kick me, I caught his heel and threw him on his back, thinking that would settle it and he would leave me alone, but he caught up to me again, dodging and taunting and doling out pugilistic clichés and disparaging remarks about my manhood.

“I don’t want to hurt you, man,” I said.

Perhaps I should’ve been more sympathetic to his situation, learned his name or that of the psychiatrist whose care he was surely under, but all his insults and impertinence and my inability to land a single punch had gotten up both my dander and my heart rate. Believing the only way to be rid of him was to properly trounce him, I wrestled him to the ground and planted his face into the snow, losing my glasses in the process.

“You’re smothering me!” he shouted. “I can’t breathe!”

I put my knee into his back and made him say “uncle,” because it was what my tormentors had demanded from me during my regular Sunday-afternoon beatings as a child. As soon as I let him up, though, he began to hop around again, assuming the same ludicrous boxing pose and issuing more preposterous remarks. “I’m doing pretty good for a drunk, aren’t I?” he said.

By now two men had appeared. I hoped they would help me or call the police, but they didn’t seem to understand that I was the victim. It didn’t help when my opponent told them I had started it.

“He’s drunk,” I replied. “Smell his breath. Now, will someone help me find my glasses?”

One of the bystanders retrieved them, and I put them on, but the lenses were covered with snow. So were the pages of the book I’d dropped.

My deranged adversary still wanted to fight. “Come on!” he said. “Try to hurt me.”

“You’re lucky I didn’t kill you, buddy!” I roared back.

Too many movies for all of us, I thought, but at least when I walked away this time, he didn’t follow.

My heart was still pounding when I reached my apartment complex, my glasses thawed but askew. Though an argument could’ve been made that I’d been the aggressor, in my agitated state I felt proud of having taken a stand against boorishness and incivility.

As I entered my building, Meghan, my neighbor from across the hall, was trudging down the corridor toward me with a bag of trash. Most occupants of my complex, as far as I could tell, had a mental disability or illness. Meghan’s speech and mannerisms suggested that she was no exception. She had a big dent in her head and dragged one leg as she walked. I had seen her several times waiting at the bus stop with some of the other tenants, but she didn’t seem to fit in with the group, standing off to the side, looking miserable and rolling her eyes at their immature wisecracks.

Wearing her usual frayed blue sweat suit and graying sneakers, Meghan plowed past me, head down, swinging her free arm, dragging that leg, and ignoring me for all she was worth. Though we had encountered each other six or seven times in the hall, she had not greeted me once, as if she were angry about something I’d said or done.

In my apartment there were two cans of beer in the fridge. I opened one with trembling hands and stared out the window at the snow while I replayed the ridiculous fight in my mind, trying to fathom this unusual person with whom I’d tangled. My encyclopedia had a chapter on personality defects. Was he a masochist? A so-called XXY male: aggressive, subintelligent, antisocial? Possibly he was a sociopath, a peculiar breed of self-worshiping fraud who seeks conflict, has no conscience, and heeds no consequence. It seemed his merry mission had been no more than to lead me to ruin.

I was imagining him now embroiled in combat with the two passersby when there was a knock on my door.

“Come in!” I shouted.

The door opened. Standing there was a policeman: blond crew cut, pale-blue eyes sitting deep in the triangular slots of a rectangular head. I thought for certain my insolent sparring partner had convinced the law to issue a warrant for my arrest.

“Jack Robinson?” the policeman said.

“No.”

“You’re not Jack Robinson?”

“No, he must’ve been the previous tenant. I’ve only lived here three weeks.”

He continued to stand there. It was plain that he didn’t believe me. My crooked, water-spotted glasses did not aid my credibility, and neither did my living in a sparsely furnished room in a complex heavily populated by the mentally disabled. I wondered if Jack Robinson — a made-up name if there ever was one — was actually my assailant. Perhaps he had lived in this very apartment before losing his mind. I would not have been surprised if “Jack” had assigned me his identity, and I now owned his rap sheet and possibly the room at the asylum from which he had just escaped.

The policeman stepped inside and asked for some identification. I found my wallet and extracted my Las Vegas casino card. He stared at the photo for a minute, then surveyed the room: the bare wood floor, the table where I wrote, the chair where I sat, my fat encyclopedia opened to the chapter on the admirable but volcanically doomed Minoans, whose lavish and sophisticated Bronze Age civilization had required neither weapons nor walls: Mycenaeans seized the opportunity given them by the eruption of Thera to oust the Minoans from their control of the profitable sea routes. Metropolitan Minoan was replaced by provincial Mycenaean, and the palaces were lost to sight and memory.

“You don’t have a driver’s license?” the policeman asked.

“I don’t have a car.”

He held my card up to the light for another few moments, then returned it with a sullen thank-you and took his leave.

The next day my glasses refused to sit straight on my face despite extensive bending, and my knee was bruised. I limped across town through the arena where Jack Robinson and I had put on our spectacular ice-dancing exhibition. Passing the Mexican restaurant, I saw my neighbor Meghan in the window in her blue sweat suit, vacuuming and pushing chairs around, a crown of sweat shining on her brow. She worked so vigorously, I feared she would break the furniture. I waved, but she only scowled, threw aside another chair, and turned away.

When I came into the restaurant to set up for dinner, the Romance Writer was sitting at the bar, his cheeks flushed from drink. We looked at each other as if we both knew I was about to say something long-winded. He acknowledged me with an aloof nod, no doubt dreading some mention of sea squirts. I mumbled a hello as I passed and tried not to hate him.

That night after my shift, Oscar, who was working fourteen-hour days, asked if I wanted to stay for a drink.

We sat at a table by a window, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott on the stereo. It was hard to make Oscar laugh while his restaurant was failing, but I succeeded by describing my bout with Daft Jack Robinson, my interrogation by the surly blond policeman, and the epic dream I’d had the night before, in which I’d broken a guy’s neck (with some trouble) and later learned that he was suing me for a sprain.

When he’d stopped laughing, Oscar sighed and stared at the rippled ice of the frozen creek outside the windows. We’d had only fifteen customers the whole night.

“It’s still winter,” I reminded him. Summer and fall are Vermont’s big tourist seasons.

“I should’ve listened to the owners before me,” he said, pouring another glass of wine. “They tried to warn me.”

During our very slow dinner hour, I had climbed the icy hill to spy on the diner. It had been jammed, as it was every night.

Oscar hated that diner as much as I hated the Romance Writer.

In the daylight social workers flitted about my apartment complex, visiting clients. I’d gotten to know one social worker named Mack, a gaunt man in his midforties with a craggy, tanned face and a ready smile. His hair was long, and he wore flowered shirts and a leather newsboy cap. He appeared to enjoy his job. I’d begun to consider social work as a fallback career in the event of my failure as a writer.

Mack caught me in the corridor one day and told me I was the last “normal” resident left. Herb, a hebephrenic schizophrenic, was moving into the apartment above mine. “Big as a lake and never sleeps. Got a telescope he likes to move from window to window.”

An insomniac astronomer. Perfect. “Is he safe?” I asked.

“We don’t let them move here if they’re not.” Mack told me Herb’s symptoms had subsided as he’d grown older, which happened to a lot of schizophrenics.

I thought of the decay chains in actinides I’d been reading about in my encyclopedia, how volatile elements such as uranium-238 eventually decayed into stable metals such as iron. All of history was like that: massive upheavals and explosions and violent revolutions that devolved into order and stability, sometimes even music and gold. I could only hope that the same would prove true for me, the turbulence of youth giving way to the iron of love and knowledge and a worthy prose style.

“What can you tell me about Meghan?” I asked Mack.

He thumbed up the bill of his leather cap. “What do you want to know? You interested in her?”

Only interested to know why she wouldn’t say hello, I told him, which was the truth.

“Meghan isn’t like the others,” Mack said, shaking out a cigarette and offering me one. I declined. He lit his, expelled a long stream of scalloped blue smoke, and told me that Meghan had been in a car accident when she was three. “She knows she’s just like you and me, but she can’t get there.”

“Any chance of a recovery like Herb?”

He shrugged. “She’s thirty-one. But you never know.”

We talked for a bit more about social work — “I’d rather be a movie actor,” he said, “but it’s all right” — and I told him I was working over at Oscar’s Cafe.

“Oh, yes,” he said. “Plan to go down there soon as that hill thaws.”

I was wrapped up in a blanket one spring night, halfway through my three-thousand-page encyclopedia, dog-earing all the good parts as if I were fourteen and huddled over a dirty magazine — The function of ritual is always to give the appearance of order, security, and meaning to the unpredictable sequence of events that characterize human life — when someone knocked on my door.

“Come in!” I shouted.

Meghan cautiously stuck in her head. “Would you like to come over for banana bread?”

I set aside my encyclopedia and threw the blanket from my lap. “Let me put on some shoes.”

Instead of her usual sweat suit, Meghan wore a plaid blouse tucked into a dark skirt and black-and-white oxfords, the shoe on her bum leg built up at the sole. She was wide at the hips, and her body twisted as she balanced on the good leg. I told her she looked nice. She thanked me with a smile, and I thought I detected a blush.

Meghan’s apartment had the same floor plan as mine, but it was the opposite in every other respect: bright, homey, neat, and packed with heavy faux-velvet chairs, hanging plants, lamps, vases, Japanese teapots, photographs. The hardwood floors were covered with rugs, and cats skulked and dashed from here to there. An illustrated, handwritten poem tacked to the wall was entitled “The Animals Are My Friends.”

“Do you like coffee?” Meghan asked in her husky, halting voice.

I said I did.

She returned with a pot of coffee and a silver tray of sliced banana bread, which she apologized for burning. The bread was a little dry but not burnt, and it was good with the coffee. I told her so as I reached for another piece. We talked about our jobs: mine at Oscar’s and hers at the Mexican restaurant.

“This summer I’m going to Cape Cod,” she said.

“That sounds like fun.”

“Peg and I go every year,” she said. “She’s my social worker. I didn’t go last year, though.”

I asked why not.

She turned to scowl at a large photograph of a man and woman and three children on her wall, then said flatly that she’d tried to kill herself.

After a stunned pause I managed to say that I was glad she hadn’t succeeded.

She told me with a pout that she wouldn’t do it again.

I asked who the people in the picture were.

“That’s my sister and her husband and their three kids,” she said with surprising vehemence. “My other sister has three kids, too. But that won’t ever happen to me.”

I took a gulp of coffee and asked why; she was still young.

Because of her “past,” she said, tearing up. Carefully she lifted her cup to her lips, wiping at her eyes with the back of her hand. “Everyone thinks I’m stupid. Even my own family. Everyone thinks I’m . . . happy.”

“I don’t know anyone who’s happy,” I said, though this wasn’t quite true. I’d known many children and fools who were happy. And Jack Robinson, who laughed at the rules and existed solely for his own mad pleasure, was a jolly sort. I wondered if I’d missed what he’d been trying to tell me, if he’d rolled out of the darkness that night to tell me something. Maybe if I hadn’t tried to teach him a lesson of my own, he might’ve shared with me some of his infantile, animal chaos, the kind that courses through the veins of children and fools and many great artists.

Meghan and I talked about the poem on the wall, and she introduced me to her cats, Loved One, Gray Cat, and Felicia. I wondered how the Romance Writer would handle this one: the thwarted novelist having coffee and banana bread with the lonely, brain-damaged woman who wanted a family.

Meghan perched her cup on her knees and asked if I ever got tired of being alone.

Sometimes, I admitted.

She seemed slightly cheered by this and offered to sing me a song she’d sung the night before in church. She put a CD in the player and followed along perfectly until she made a mistake. It was the same spot where she always made a mistake, she said. “I can’t get it right.”

“You hit all the notes,” I told her.

“I’ll never learn.”

“You have to keep trying.”

Autumn, said the encyclopedia, when the fertility and vigor of summer give way to the death of crops and the failing strength of the sun, is associated in mythology with the dying hero or god. It was also the time when the leaf lookers came to Vermont in droves, and though a few busloads of them ventured down the hill to Oscar’s Cafe, it wasn’t enough. For lack of a better plan, however, Oscar was going to stick it out until the bitter end. He was up to five packs of smokes and a full pot of coffee a day and had begun having panic attacks.

I didn’t know what a panic attack looked like until one evening, just as we were opening for dinner, his cheeks drained of color, and he fell to one knee, unable to breathe. He grasped the counter, his face contorted in terror. I knew his father had died young of a heart attack, so I presumed Oscar was having a heart attack, too. Forgetting what little I knew about CPR, I flew to the phone and dialed 911. Within minutes the ambulance jerked to a stop out front, and the EMTs whisked Oscar away. I put up the CLOSED sign and trudged home.

Oscar returned to work the next day, as gray as the grave. He’d finally accepted that the restaurant would go under and that he would have to return, as most of us do, to the security of working under someone else’s dominion. I think it came as a relief.

A few weeks later, after selling his cafe, Oscar packed up and left for Washington, D.C., where he’d landed an executive-chef spot in a prestigious hotel. He figured he would be in debt for another twenty years, but it was better than being dead. He was looking forward to regular paychecks, mere sixty-hour workweeks, appreciative urban palates, markets with every fresh spice and fish and fruit available, and holidays on which he didn’t have to take inventory and clean the grease trap. He was smiling again, at last.

I stayed in Middlebury for a spell, trapped by work on another lifeless novel but intent on leaving soon. No airplanes this time. My next move would be under difficult circumstances, with a minimum of cash, to an unfashionable city where I would find a low-paying job and rent a crummy room so that I could capture the turmoil in a new novel, where, like a pellet of uranium-238, it might decay into a precious metal and at last bring about my metamorphosis.

By now I’d relocated into cheaper quarters across town, a studio with a small kitchen where I’d set up a table to write and continue my Guinness Book accumulation of rejection slips. My new apartment also had free cable. When you live alone, television’s powerful illusion of human interaction will sometimes make you feel more depressed than you actually are. I had developed ways to deal with this: I would make popcorn with butter and listen to the radio. I would have a rejection-slip party all by myself with singing and beer. I would take long walks out past the city limits as the sun went down.

Returning one evening from such a walk, I heard a shout in the distance and imagined it was the bellowing of my old rival, Jack Robinson. I considered the concept of antimatter: for every particle of matter in the universe, the theory goes, there is an equally but oppositely charged particle of antimatter; when the counterparts meet, both poof into nonexistence. I decided that Jack was not a gift or a lesson or a catalyst for personal transformation, but an antiperson, my antiperson, Death in the flesh, and I resolved to postpone all meetings with him indefinitely.

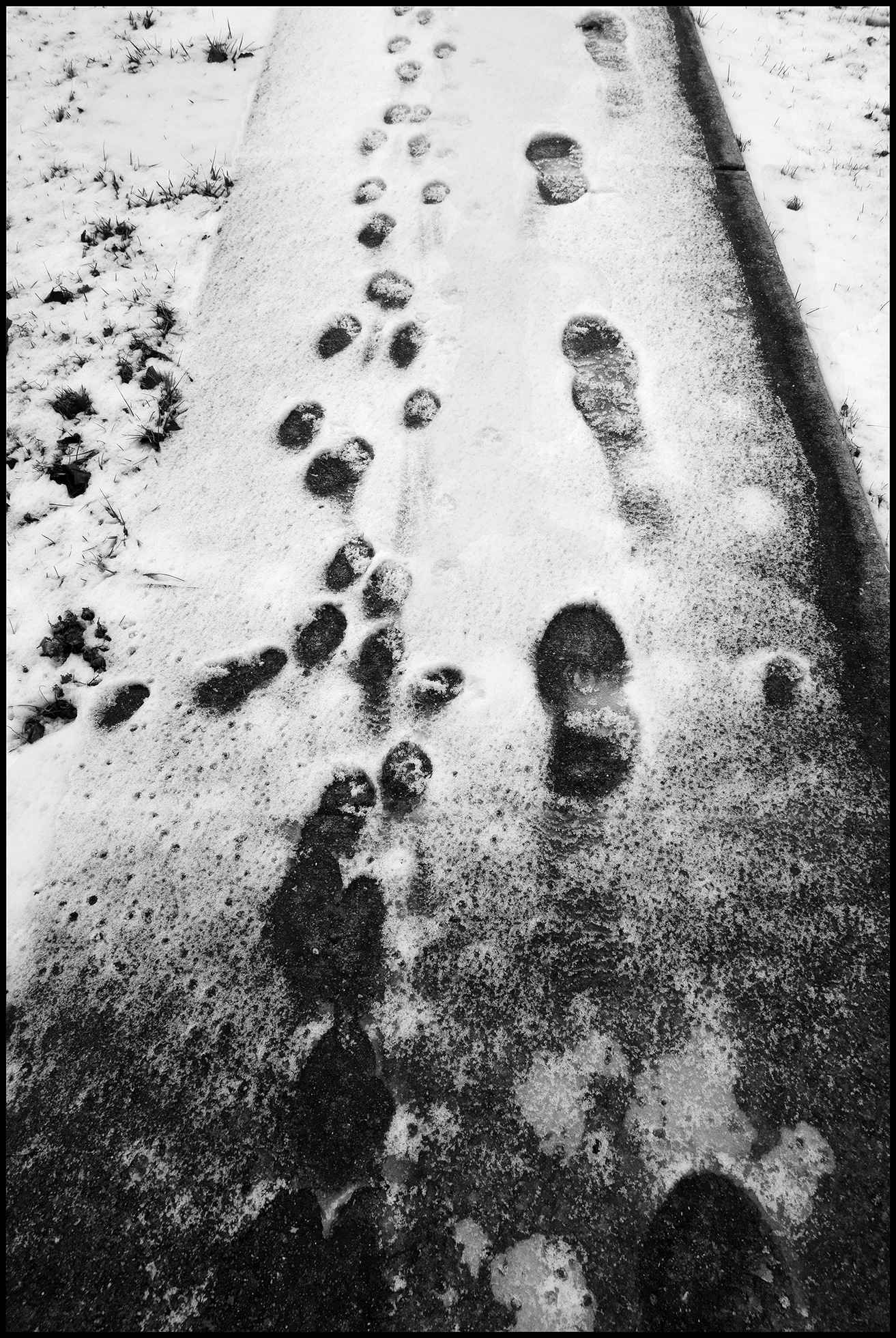

It was on this night in early winter that the first heavy snow of the season began, the great flakes spinning down like crystalline wheels. The town seemed like a winter scene inside an ornamental glass ball: a mother was teaching her young daughter to ride a bicycle; a child of about eight was standing on his front lawn delivering a speech to no one; a small boy teetered toward his beaming father.

Passing the Mexican restaurant, I saw Meghan at a table by the window, a man across from her, a candle lit between them. They were leaning intently toward one another, their radiant faces only a foot apart. I slowed and stared in at them, the snowflakes tumbling all around.