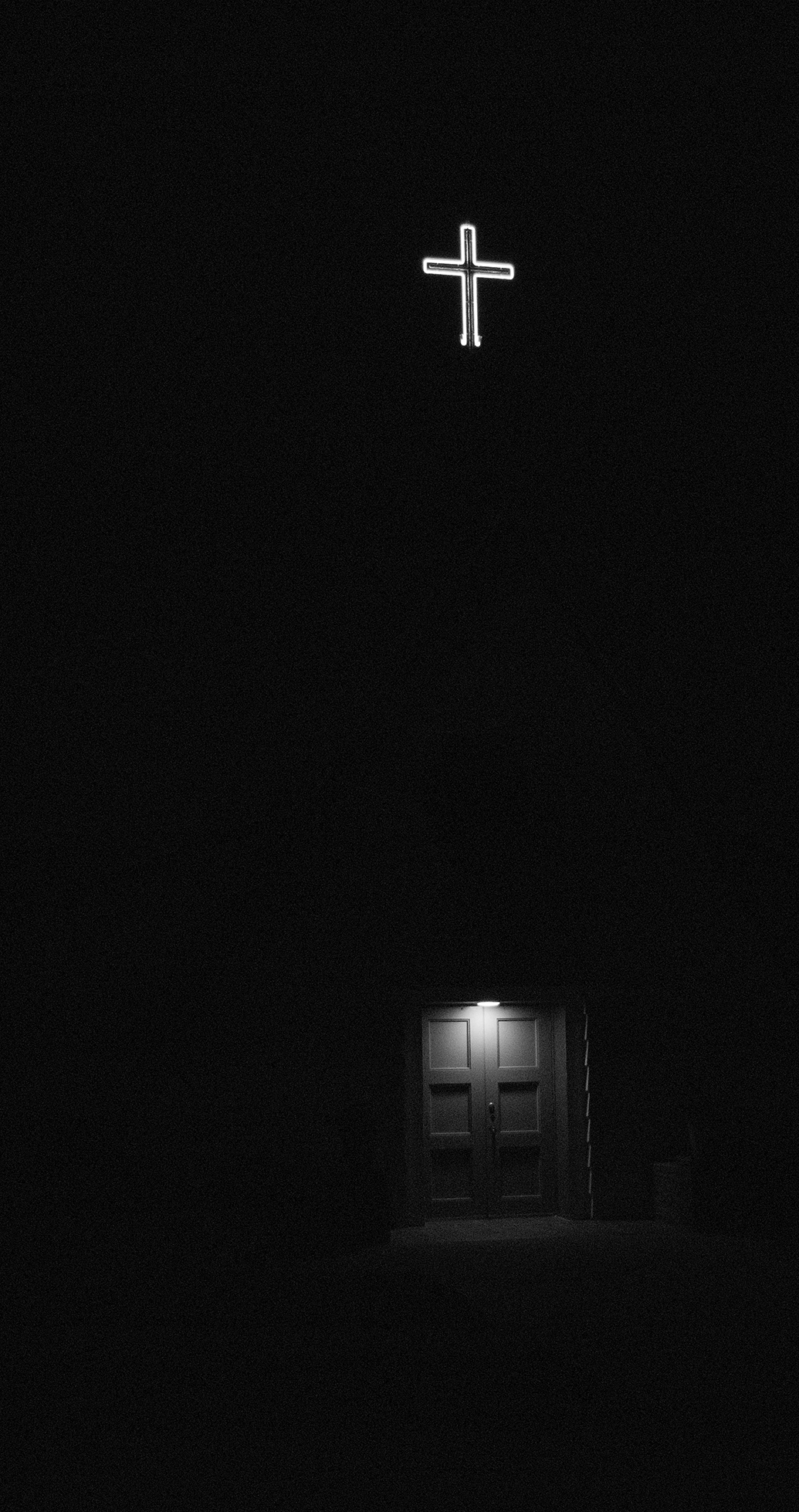

While other kids were listening to fairy tales and learning to finger-paint, I was at Saint James Church learning the numerology of good and evil: three Gods in one, seven deadly vices, the Ten Commandments.

I was nine years old when a parakeet flew into my father’s office on Robert E. Lee Boulevard. I named the bird “Boulevard” and was given full responsibility for her care. But oh, I was a lazy child. If you’d asked me what I wanted for Christmas, I’d have said, “A slave.” What I’d have meant was somebody to wait on me, do my homework, clean the bird cage.

Boulevard’s cage would reek before I’d bother to clean it. And I wasn’t exactly punctual with her food and water either. Not surprisingly, Boulevard never warmed up to me, always backing to the other side of the cage when I was near, never singing for me. But let my brother, Mike, come to her cage, and she’d hop on his finger, nuzzle, and sing all her favorite tunes. Mike got all the attention in the family.

Then I ran out of bird food. Oh, well. I’d get some tomorrow. But every day I’d “forget” to buy bird food, and every day Boulevard would move less, chirp less, and sing not a note.

Was it a week, or more, or less that I spent starving Boulevard? I don’t know. But one day I came home from school, again with no birdseed, and she lay dead on the filthy floor of her cage.

I never confessed to parents or priest. Was it the deadly vice of sloth or envy, or the mortal sin of murder? Whatever its number or category, I felt damned. I went on to learn the one rule that matters most: be kind.

Kate Dwyer

Port Townsend, Washington

When my son, Kyle, was a high-school freshman, we took him to the emergency room with severe abdominal pain. The doctor suspected appendicitis but told us an X-ray would be necessary to be sure.

Ever since Kyle had been a small boy, illness had brought confessions out of him. Once, at the age of seven, weakened by a playground injury, he’d apologized for giving the baby sitter a hard time. At home with a fever, he would lie with his hands folded over his chest and earnestly pledge his love to his sister, whom he normally teased mercilessly.

After the doctor left to order the X-ray, Kyle lay quietly, looking concerned. Finally he said he needed to tell me something.

“Before they see it on the X-ray,” he said, “I think you should know that, well, sometimes I smoke cigarettes.”

He said he was sorry; he knew it was a stupid thing to do, and he hoped I wasn’t too disappointed in him. He apologized for letting me down.

I told him he needn’t have worried; it wouldn’t show up on the X-ray. Also that I hoped he would quit smoking because of the health risk, but that it was his decision. And I told him I loved him.

I hated to see my son ill, but I loved how he told the truth when he got sick. That’s my confession.

Carrie Thiel

Kalispell, Montana

There are two categories of people in my life: those who know I killed a teenage girl in a drunk-driving accident, and those who don’t.

It happened more than twenty-five years ago. Since then, the number of people who don’t know has grown, while the number of people who do has remained about the same: My family knows. I told my children when they were in middle school. (We visited the cemetery together.) I have old high-school friends who know, and certain therapists.

The people who don’t know are many: My boss. My co-workers. My children’s teachers and their classmates’ parents. The people I chat with in the grocery store. My dearest friend in the town where I now live.

I could have chosen to tell my story in schools to warn kids about the dangers of drinking and driving, but I didn’t. I live quietly. I sometimes wonder if I am living a good-enough life.

I recently connected with an old friend on Facebook, and he told me he had come across a letter I’d written to him shortly after the accident. (I mentally moved him from one list to the other.) He wasn’t sure what to do with the letter and asked if he could send it back to me, as it seemed too important to discard. I agreed. I didn’t remember what I’d written.

The letter sits in a box on my desk. Sometimes, in an organizational spree, I’ll come across it. My first reaction is always “Why haven’t I opened this letter addressed to me?” Then I remember — it is my raw, handwritten confession, not softened by years. There might be details in there I’ve forgotten, and I can’t bear to recall any more than I already do. I also worry that the words I chose will now seem painfully inadequate. The letter remains unopened.

Name Withheld

I barely knew my mother when, at the age of thirteen, I moved to California to live with her. She was more than ten years clean and sober by then, but she’d substituted other vices for her old ones. Her top priority was her boyfriend, and she spent most of her weekends with him. While she was gone, I drove my friends around the city in her other car and smoked cigarettes.

Then her boyfriend moved in with us. He and I were not the best of friends, and I was bitter that I would never get back those years with Mom that I’d missed. One weekend I stayed out overnight without permission. Upon my return Mom and I argued, and she told me to leave and not come back. She gave me five dollars for a taxi and another five dollars for a pack of cigarettes. One month after my seventeenth birthday I became homeless.

I made four rules for myself: you will not sell your body; you will not do coke or smoke crack; you will not get pregnant until you are ready; and you will graduate from high school.

I found a small apartment, but I still needed money. Then someone offered me a chance to earn a few hundred dollars, and I made my first drug deal. He fronted the dope, I sold it, and we split the profit 70-30. I paid bills with half the money and saved the rest. I eventually renegotiated the split to 60-40, then 50-50. Finally I began buying my own supply and keeping 100 percent. I was my own boss and had many loyal customers.

I graduated, but Mom did not attend the ceremony. When I attempted to register for college, she would not provide her income information, so I couldn’t apply for financial aid.

Meanwhile I became a master at the “game.” Attempting to maintain my humanity, I gave candy and toys to customers’ children and even walked them to the mailboxes to see if their mothers’ welfare checks had arrived. Male drug dealers often terrorized female customers who asked for deals or credit. I, on the other hand, gave credit and deals freely. The customers became my family, my eyes, my lookouts. They did my laundry and grocery shopping. When I got picked up in a sting operation and placed in a lineup, their children pointed to the other dealers but not to me. To them I was the nice candy woman.

With the other dealers in jail, my profits multiplied. I established hours of operation and charged “after-hours” rates.

Late one evening I hopped on my bike to deliver a package, not knowing it was against the law in California to ride a bike at night without a headlight. A police car’s lights flashed, and I stopped. Two officers got out: a white male and a black female. The male officer asked if I would object to a search. Too scared to think straight, I said sure. The drugs were in a hidden pocket of my Charlotte Hornets jacket.

The female officer put on gloves and patted my shoulders, arms, back, legs, and ankles. She threw my box of Newport shorts and my California ID on the ground. Then she felt around the bottom of my coat and grabbed the package. I said a silent prayer to God to spare me.

Her hand still on the package, she locked eyes with me. Hers were steely and disappointed; mine were pleading. Then she said, “She’s clean.”

The officers followed me home to ensure my safety. After they drove away, I delivered the package, but that was my last deal. I flushed the rest of my stash down the toilet, got a new apartment, and went from making four hundred dollars a day to six dollars an hour at Taco Bell.

I believe that female police officer saved my life. Fifteen years later I still see my younger self as resourceful, strong, fearless, and determined to survive, but instead of defiling my community, I now edify it. Instead of hating my mom, I forgive her. Instead of carrying around guilt and shame, I share my story with youngsters who can benefit from it.

Nikki

Catholic schools start training students for the sacrament of confession at about the age of six. To a first-grader the concept is confusing. The nuns gave us detailed lists of sins, some of which I’d never even heard of. I thought maybe I’d committed some of them without meaning to.

By the time my first confession arrived, I had studied the lists and made up my mind what I needed to admit. I entered the confessional and knelt in the darkness, and the sliding door covering the screen slid to one side. I started to recite what I’d rehearsed. When I came to the part about my sins, I said, “I have disobeyed my parents four times, lied once, and committed adultery.”

There was a snicker from the other side of the screen. I didn’t know why. It was true: I had tried to act like an adult. I hadn’t even known it was wrong.

Adrianne Borgia

Oakland, California

I joined the Peace Corps in my early twenties with a sincere commitment to service but also to discover if I was really a lesbian. I felt sure that living on the other side of the world from the two women I thought I loved would reveal the truth.

Before the plane even landed in Cameroon, I was already desperately missing both of them.

After a few months I decided to have “the talk” with my parents. I considered writing each of them a letter (they were divorced), but I decided against it. I wanted the conversations to be face to face. I waited until my next trip home to the States.

Mother was first. One night, after dinner and many cocktails, we were sitting on the deck overlooking her beautiful acreage and enjoying some girl talk. I took the opportunity to tell her that I dated other women.

After an extended sigh she set her drink on the table and said, “Well, I thought I would cry when you finally told me, but I’m not. So. Tell me who she is.”

Dad was going to be tougher. We had a golf date on Father’s Day, and we stopped by the liquor store to pick up some beer on the way. With a few minutes before the store opened, we were standing in the parking lot, playfully kicking gravel at one another, when I said, “Dad, I need to tell you something.” And I let him know about my dating women.

There was a pause as the owner of the liquor store unlocked the door from the inside. Dad waited for him to walk away, then told me he was relieved. He’d thought I’d found an African boyfriend. “I’d rather you date a woman,” he said, “than a black man.”

M.S.

West Conshohocken, Pennsylvania

Here I am, sitting on the edge of the tub — because at my age I’m no longer able to stand with one foot on the rim and the other on the floor — and slowly performing a task I have done for most of my adult life. I am shaving my pubic hair.

One could say that shaving has become an addiction of mine. I feel uncomfortable and testy if I don’t do it. It’s a habit spawned long ago, when I was a robust young woman and had many lovers. One along the way suggested that I should remove the black thatch of hair to make it easier for him to give me pleasure. I don’t recall his name, but I vividly recall that he was well worth humoring. Even though it was virtually unheard of in that era for a woman to shave “down there,” I kept up the routine, secretly enjoying the shock value of my hairless mons whenever I took a new lover.

Now and again I would start to let the hair grow back out of curiosity. Would it still be the heavy black triangle it once was? But I could never go more than a day or two before I was once again shaving it away.

You must wonder why, at my advanced age, I even bother. Who will see it now, save my gynecologist and the undertaker? Will the latter laugh to himself upon discovering that this birdlike woman with the silver locks is sporting freshly shaven nether regions, or will he muse at what a lusty broad I must have been?

I can tell you this: whether I am singing in the choir at church, standing in a grocery line, or sitting through yet another dreaded board meeting, all I have to do is think of that clean pink patch, and it makes me feel so damn sexy.

Name Withheld

“Listen to me!” I screamed into my cellphone. My parents, both on the other end, fell silent.

It was not quite midnight, and the snow was beginning to fall in what would be one of the largest snowstorms in a decade. I had just dropped my friends off at their dorm. We’d planned to go out that night, but I’d abruptly insisted that I needed to go home, leaving them at the curb with an apology. Now I sat alone in my car, scared.

I loosened my grip on the phone and told my mother and father that something was wrong with me, and I couldn’t take it anymore. I took a deep breath. My eyes welled with tears. “I need help. Please.”

I stared up at my towering dorm, until recently one of the few places that had provided a refuge from my crippling anxiety. Now being in that dorm had become unbearable. I had nowhere to go. My sense of self had crumbled. For months on end my heart had raced, even in the most relaxed settings. I’d walked out during lectures. Studying had only made the symptoms worse. As had socializing. As had eating. As had drying my hair. I could not escape myself.

I’d filled my ears with soothing music. I’d changed my room’s decor to sunny pastels. I’d read empowering books. I’d tried to exercise it away. I’d prayed. But nothing had worked.

After a long pause my dad said, “We’re coming to get you.”

They pulled up at two in the morning to find me standing under an overhang with my hands in my pockets and my jacket hood covering my head. I had nothing with me but my phone and a tube of mascara.

I opened the back door and got in as if I were surrendering to authorities. In a way I was. Staring through the falling snow at the occasional passing headlights, I decided to surrender to any stigmas that might come with a diagnosis of mental illness. It was the first step toward regaining my life.

Melissa Brady

Lumberton, North Carolina

All the distractions were gone. Our children were grown and had kids of their own. I had retired. After thirty-seven years it was just my wife and I.

We’d both been raised in Christian homes but had abandoned fundamentalism decades earlier for its more respectable cousin, Evangelicalism. That wasn’t working for me either and hadn’t been for a long time. The Church had no vocabulary for what I was going through.

I came home from therapy one night and told my wife what the therapist had said about our marital problems: “Well, your wife is not a lesbian, but you kind of are.”

I had confessed to my wife a mere eighteen months into our marriage that I felt like a woman inside and didn’t identify with my male body. Yet somehow we’d kept moving forward: raising a family, volunteering at the church, and doing good works. It had worked for a long time, but now these feelings would not be ignored.

“Can you be my husband or just my friend?” my wife asked.

“If it has to be one or the other,” I said, “then just your friend.”

It was a relief to tell her the truth. We looked around our beautiful house on the water, flipped through pictures of our grandchildren, and counted our blessings. Then she went to bed, and I sat on the couch and cried.

It’s now six months later, and she is out of the house, spending the evening with an old high-school boyfriend. I am reading about testosterone blockers and estrogen patches. No one asks for this. Not ever.

Name Withheld

I am a preteen with budding breasts and a budding curiosity about kissing. What does it feel like? How is it done? One day my friend and I decide we should practice. We go down into her dark basement, where we huddle in an even darker space underneath the steps, and we kiss — first tentatively, then warmly. We are pleased to discover that this activity comes naturally to us, and we start plotting to kiss actual boys.

Though I’m not at all guilty about this behavior, the next time I go to confession, I feel compelled to tell the priest. Perhaps I am looking for reassurance that what I’ve done is normal.

I get in line for Father Miles, who is stern but gentle. When it is my turn, I enter the confessional, kneel, and recite, “Bless me, Father, for I have sinned. It has been one week since my last confession.” I tell him my tale.

Father Miles plies me for details, then gives me a longer penance than I have ever received before (many Our Fathers and Hail Marys). I am blushing as I exit the box.

Some time later Father Miles and I cross paths, and to my surprise he asks me what I plan to do with my life. When I tell him I’m not sure, he strongly advises that I consider becoming a nun. I quickly draw the connection between his advice and my confession: girls who kiss girls belong in the convent.

Name Withheld

My mother grew up in a small Midwestern farming community. There was plenty of tragedy in her family: her brother died in a car accident, and her mother suffered from mental illness. My mom was reared partly by a strict and bitter grandmother. The only toy she ever had was a box of crayons, and the only book she ever owned was an old dictionary.

In high school my mother was a popular, straight-A student. She led the marching band, was a cheerleader, and belonged to many civic organizations. She dated the same boy for seven years, but she finally broke up with him because he lacked ambition, she said.

I met this former boyfriend, B., thirty years after he and my mother had parted ways. He walked up to me in a bar in Arkansas and said, “You must be A.’s daughter.” He was awed by my resemblance to her. He asked how she was doing, and as I gave him a brief history of her life, his eyes grew moist. I realized then that he still loved her. I felt uncomfortable and wondered if I was somehow betraying my father by having this conversation. When a tear finally rolled down B.’s cheek, he took my hand, asked me to tell my mother he said hello, and left.

What I hadn’t told him was that I’m not sure my mom is happy with her life. She would never say so, but there’s a sadness about her.

My mother has been married to my father for nearly fifty years. From the day of their wedding he always treated her with an air of superiority, as though she were a helpless calf that had wandered off the farm and he had rescued her. He loved her, but he showed his love by trying to “improve” her. He told her what knife to use, what to wear, what to order at a restaurant, what friends to see. She would do nothing without his permission. He became president of a large company and took my mother all over the world, but in front of his colleagues he would correct her pronunciation and remind her of her country origins.

Today my mom will scarcely say a word in public. She has to think carefully before she speaks, and she will often cut herself off and say, “Oh, I’m so ignorant. I hate to make a fool of myself. Will you explain what I mean?” My siblings and I always went to our dad for help with our homework; all our mother did was cook and clean and drive us everywhere — what did she know? She once revealed to me that she had always dreamed of getting her college degree, but she’d dropped out when she married my dad.

My mother just turned seventy, and before her birthday I mailed letters to all her childhood friends, asking them to send birthday wishes. After I’d done this, she pulled me into the kitchen and wanted to know if I’d mailed one to B. I said I had. She smiled shyly and confessed that he was the best friend she’d ever had. “He is the only one on this earth who really knows me,” she said. He’d been there when she was going through so many hard times with her parents, and he’d known her brother and how much she loved him. “He knew the best of me,” she said.

A few days after her birthday, my mother came to my house to tell me she’d received a letter from B. In it he’d told her that she was the smartest person he had ever known. My mom was beaming. “I read that to your father, and he said, ‘Well, I could have told you that. You are smart.’ ”

It may have been the first time he’d said that in fifty years. She looked different, and I think I caught a glimpse of the happy high-school girl I had never known.

Name Withheld

Unlike most Catholic children, I eagerly anticipated the sacrament of confession. My family avoided drama, but I lived for it and always made sure I embellished at least one sin in the confessional, turning anger at my father into wishing him dead, perhaps. I watched the priest’s reaction to everything I said and even tried to make eye contact so he would see how desperate for forgiveness I was. Confession was like a drug to me. When it was over, I would kneel and say my penance, high as a kite.

In my twenties, after making some mistakes, I entered a twelve-step program. I could barely hear what the others shared as I mentally rehearsed ways to make my story as riveting and emotionally fraught as possible. The truth was I’d had a relatively easy time of addiction, and the bare facts would hardly have impressed. So I stretched the truth, eager to see these strangers riveted by my story: so much chaos and pain, and yet such wit, such wisdom. Needless to say, I didn’t make any true friends in meetings, although I did have a number of admirers.

About the same time that I began recovery, I also started therapy. All my therapists eventually saw through my exaggerations, but I still relished having each one’s undivided attention for a whole hour every week. As the years went by, I developed — or created — new problems for the therapists to help me solve.

I’ve had twenty-plus years of therapy and twelve-step meetings. These tools that were supposed to help me learn how to live a fulfilling life instead fed my addiction to myself. I have little genuine interest in others and don’t know how to have meaningful conversations. I still have no close, lasting friendships. The enticing sizzle of my confessions sometimes draws people in, but after a while they go searching for friends who know how to reciprocate.

I am tired of hearing myself talk. I would like to learn how to listen, how to reach out and offer help without being asked. I want to know what it’s like to know another person instead of always needing so badly to be known. But I strongly doubt that this is my last confession.

Name Withheld

My deceased husband killed three people. I believe that no one but me knows this. One man he shot. The second he tied to a tree in the woods and left to freeze. I don’t know how the third met his fate.

I’ve imagined these murders in more detail than is likely good for my soul. I picture the first man in his car, the pistol aimed at the base of his skull. Does he see the gun before he is killed, or is my husband quick about it? Then I imagine the man slumped over into the passenger seat in an unnatural way, almost contorted. My husband walks away quickly and confidently, tossing the gun. The man had a family, or so I imagine.

Then there is the one who freezes to death. He is young. He owes someone money, maybe even my husband. He has been beaten, and he is in the woods. (I think of what my husband used to say when he saw someone behaving rudely: “If you can’t live among people, go to the woods and live among the wolves.”) It is cold, and the man is bleeding and bound to the tree. I wish for the mercy of alcohol or drugs to numb his fear and pain.

As for the third man, my husband told me only, “It was me or him,” and that they were friends. Then my husband cried. He cried for all of them. Maybe he felt as if he should have gone to the woods to live among the wolves.

My husband was recently killed in an accident. Perhaps death released him from his guilt, and he found peace.

Meanwhile here I am, the grieving widow, living in the suburbs, waving to my neighbors, making small talk about the hectic life of a single parent. Here I am going to and from my job, where my co-workers, like me, have doctoral degrees and egalitarian ideals about serving the underserved. Here I am carrying my husband’s guilt, his shame. I’m smiling, but inside I want to scream.

Name Withheld

I dated Paula for a year. She always drove whenever we went to dinner or the movies because I didn’t own a car. More often than not she paid for the date too, because I worked for minimum wage at a nursing home and she was a car salesperson. I felt a little emasculated by this arrangement, but that was OK. What wasn’t OK was that Paula sometimes got drunk and argued endlessly with me. I tried to put up with it because I really cared about her, but it got on my nerves.

One day I was going to meet Paula for lunch, and as I unlocked my bicycle from a telephone pole, the key slipped from my fingers and fell through the sewer grate. After cursing at myself, I went to a pay phone to call Paula and explain what had happened.

“You always do this to me!” she shouted. “You are always fucking up everything!” She went on like that for a while, then hung up. I returned to my bicycle, feeling terrible about myself. I stared at the chain that held the bike fast to the pole and thought, That’s me. I’m chained.

I went back to the pay phone and called Paula. I told her I loved her, but I couldn’t take this anymore. I was breaking up with her and didn’t want to see her again. I closed my eyes and waited for another rant, but there was only silence. Then she said, “Wait. I’m picking you up.” She wanted to explain.

I agreed to have lunch with her, but I insisted I would walk to the restaurant.

When I got there, she was at a table and had a file folder in front of her. “My therapist always tells me that losses set us free,” she said. “Maybe now I’ll know if he’s right.”

Therapist?

The file folder contained her medical records. She had been in three different mental institutions, had attempted suicide six times, was bipolar, and had been on just about every drug there was. In a matter of an hour she told me about being molested by three uncles, her mother’s suicide, the stillbirth of her baby when she was married, and how she could not have any more kids.

She wasn’t trying to change my mind, she said. She could tell by my voice I’d had enough. She just wanted me to know why she might be the way she was.

She had tears in her eyes. I did too. I shook my head and asked why she hadn’t told me all this at the beginning.

“Because I didn’t want to lose you,” she said.

I wonder if she understood the irony of her words. We never saw each other again.

Name Withheld

When I was six years old, I experimented sexually with the boy next door in his tent. He was twelve and sometimes gave me presents. I remember a rabbit’s foot for taking him in my mouth. His penis disgusted and gagged me, but I really wanted that lucky charm. I also let a boy my age see my genitals in exchange for a glimpse of his as we hunkered in a deep trench dug by the city. And I showed a friend the many things the boy in the tent had done to me. She and I practiced the art of “what the boys do” more than once.

I knew all of this was wrong, and I harbored a fear that I was evil. I never connected my early sexual activity with my father’s strange behavior. When Mom left at night to socialize, Dad often came to my bed and climbed on top of me and made bucking motions. Once, I told him, “Daddy, I’m not your horsie.” (I have never forgotten how difficult it was to say this to him.) Most of the time I just let him do it.

One night Mom and I were alone in the house. I lay in bed, feeling ashamed and thinking, I’ve got to tell her. I got up and padded to the couch, where she sat reading. I was shaking. She grabbed a blanket and tucked me in beside her, asking, “What in the world is wrong, honey? Are you sick?”

I told her about the boy in the tent. I told her about the other boy in the trench. I told her about my friend and me.

She hugged me tight and said I was a wonderful girl, but I should stop doing those things, because people would get the wrong idea about me.

“Do you have the wrong idea about me?” I asked.

No, she said. She loved me very much and just didn’t want me to be so miserable.

I promised I would stop, and I did.

Perhaps Mom told the neighbors, because the boy next door never approached me again. I still felt strange every time I looked at the trench boy in school. I stayed good friends with the girl, but when she asked me if we could do “that” again, I said no and pushed her hands away.

I never told Mom about Dad. I came close, but I was afraid of what would happen to us if I did. Even at the age of six I knew about divorce. And, besides, I loved him.

Name Withheld

The church was full for my dad’s memorial service. He’d been one of the most renowned Methodist ministers in Maine. During the service there were many moving remembrances of him.

One woman said he’d taught her a life lesson nearly forty years earlier: One morning in church Dad had started the service by holding up a pair of pants someone had donated to the clothing drive. The pants were torn, and he was disgusted and let it show. His message was: give from what you value, not from your excess or, worse, your waste. This woman said she had tried to live by that principle ever since.

At home afterward I called a woman who’d been unable to come but had sent condolences. Telling her about the service, I mentioned the story of the pants.

“That was me,” she said. “Those were my pants.”

She told me that the pants had been in her laundry room to be mended when she had asked her daughter to get some clothes together for the drive. The daughter had mistakenly taken the pants. “I felt so embarrassed,” she said.

That morning forty years earlier my dad had provided one woman with a powerful life lesson, but another woman still remembered what he’d said with shame. She’d never told anyone.

Peter D. Beckford

Clifton, Maine

I was in public-speaking class in my freshman year of high school when I saw my best friend, Sarah, heading out the classroom door with a bathroom pass. This was third period, right after lunch.

Sarah was the first real friend I’d ever had. We’d met in middle school and had been through a lot together. In fact, we weren’t allowed to see each other outside of school due to the time she’d run away from home and hidden at my house. When the cops had come to my doorstep, I’d lied and said I hadn’t seen her.

The point is, I would have done anything for Sarah, and I sometimes felt that it was my job to take care of her, to shelter her from some of the pain that I’d experienced.

I slipped from the classroom without the teacher noticing and headed in the direction of the bathrooms. I didn’t want to go barging in, in case I was wrong. Sarah had promised me it was over, but I also didn’t doubt my instincts. I tiptoed into the bathroom and waited by the door for the noise I’d heard so many times: the gagging, followed by a choked cough, and then the sound of vomit hitting water. It came once. Then again. And again. I didn’t know what to do. I couldn’t very well break down the stall door, so I just waited. I pictured Sarah bent over the toilet, jamming that little pink toothbrush I knew she carried everywhere down her throat. I was glad I hadn’t eaten lunch, because the thought would have made me sick as well.

When Sarah stepped out of the stall, I gave her the most pissed-off expression I could muster. She opened her mouth to explain, but I turned and went back to the classroom. Sarah came in minutes after me, eyes red from crying. I’d told her before that she was sick and needed help. She didn’t realize what she was doing to herself.

After not eating all day, I was starved when I got home, and I made myself a huge dinner: a sandwich, some soup and chips, and a bowl of ice cream. Eating all that food made my stomach feel as if it might burst. I changed into some pajama pants, turned on the TV, and waited patiently for my mom to head to night school and my sister to go off with her friends. But my sister took a long time to leave. I sat there feeling antsy, worried my stomach would start to digest the food, and I would be stuck with those calories forever.

Finally my sister backed out of the driveway, and I raced to the bathroom, flipped on the fan, got down on my knees, and reached down my throat with my finger. I didn’t breathe, because taking time to breathe would have stopped the flow. I also didn’t remove my finger, because I wanted to get as much out at one time as I could. I let the vomit run down my hand before I rinsed it and started again.

When I was done, I felt empty and guiltless and good about myself. I was strong enough to handle this. But I could never tell Sarah. She wouldn’t have understood why it was OK for me and not for her.

Name Withheld

When I was in college, my friends and I played drinking games to quicken our intake and numb ourselves faster. One night Raz asked about a scar on the back of my hand. Already drunk, we immediately turned the question into a new drinking game. The rules were: Choose a scar and tell its story. No lies. If the story is deemed “worthy,” then you have to chug your drink.

I told the story of the C-shaped scar that ran between my right thumb and pointer finger, curving like a crescent moon:

I was nine. My stepfather was on the couch, drunk, and he slipped his hunting knife out of its sheath. I had seen that knife many times, most often tearing through the blood-stained fur of a prize buck when he gutted it.

My brother was there too. Our step-father staggered to the bathroom, leaving the knife on the couch. While he was gone, our kitten jumped up on the cushion where the hunting knife shimmered. I instinctually grabbed the knife, not wanting the kitten to end up like the bucks.

Just then my stepfather reentered the room and saw me. He asked my brother to hold his beer, and he told me to give him the knife and put my hand on the table. I had no choice: I laid my hand down. My stepfather held my wrist as he slowly, meticulously cut a C into the back of my right hand. My blood dripped from the wound, to the table, to the carpet. My brother began to cry. All I could think about was the deer.

“Touch that knife again,” my step-father said to me, “and I’ll fucking kill you.”

When I’d finished telling this story, none of my friends spoke. All of us lifted our cups to our lips and swallowed.

“You’re full of shit,” someone finally said. “I thought we couldn’t lie.”

For a moment I felt sick. I had drunkenly told the truth after years of hiding it. I thought of the scars my friends could not see: the drowning of my kittens, the blood on my mother’s face, the twelve-gauge shotgun, the cat-o’-nine-tails, the police, my broken arm.

Then I forced a smile and said, “Shit, I forgot!”

Name Withheld

I watched the roller-coaster car creep to the crest of the ride’s steepest hill. I imagined my son, George, and me on it, and I grew frightened: of the height and of the ridiculous yet persistent thought of my son falling from the car. When the coaster sped down, its passengers screaming, I began to sweat.

George looked at me, eager to experience the rush. “I can’t wait!” he said.

I asked if he was afraid. Was he sure he could handle it? Was he going to get sick all over me?

He just laughed. Nothing could keep him from that ride.

“George?” I said.

“Yeah?”

“I’ve got to tell you something.”

How could I say this? I didn’t want to lie to my son, but I also didn’t want to disappoint him.

“I’m scared to get on that roller coaster,” I said.

I could only imagine what he was thinking. He had heard of the wild life I’d lived, heard about my doing time, seen the gang tattoos covering my arms. He believed that nothing fazed me, that I was a tough guy. The truth was that the life I’d led before my kids were born just wasn’t in me anymore. As I’d watched them grow, I’d grown too.

George patted me on the arm and said, “It’s OK, Dad.” He took my hand, and we got out of line.

Edward Cortes

East Hampton, New York

In the months before my mother died, she and I sat and talked in her small, floral bedroom. She was eighty, and in a hoarse voice she told me stories of her life, many of which I had never heard before.

She had pilfered a handbag from Bamberger’s department store in Newark when she was fifteen. It was a leather clutch that fit nicely under her coat. Ever since her mother had died the summer before of a heart attack, my mother had felt entitled to take anything she wanted from the world.

At seventeen, to escape her father and his new wife, my mother married a pharmacist twice her age who wore bow ties and bowler hats. She didn’t love him. They had the marriage annulled.

Two years later she boarded a flight to Paris, where she met a French Canadian with thick, dark curls named Arthur. They had sex in a dimly lit hotel room, then walked the cobblestone streets. The silk stockings that Arthur bought her made her feel prosperous. After she returned to the States, Arthur sent her flowers every day. The bouquets kept coming even after he’d taken up with another woman; he had forgotten to cancel the order. My mother would never quite get over him.

As the Second World War raged in Europe, my mother landed a job as a banquet manager in a prominent hotel. There she met my father, a major in the army with a Harvard degree. He promised her protection and took her to the suburbs, where she became a conventional wife and mother.

After that, her daydreams became more vibrant than her waking life. My mother envisioned herself as a frequent guest at the Algonquin Round Table, where she would match wits with Dorothy Parker, rub shoulders with the literati, and have lovers instead of a husband. These fantasies would sustain her through a divorce, a third marriage, widowhood, and long years alone in Florida.

“If I had gotten the life I wanted,” my mother said to me, “you and I would never have met.” I waited for an ironic barb to follow, but she surprised me: “And that would have been too bad.”

S.H.

New York, New York