Innocence ended at 8 in the morning the day after Labor Day, 1959.

“Boys and girls,” the nun is saying. “Boys and girls.”

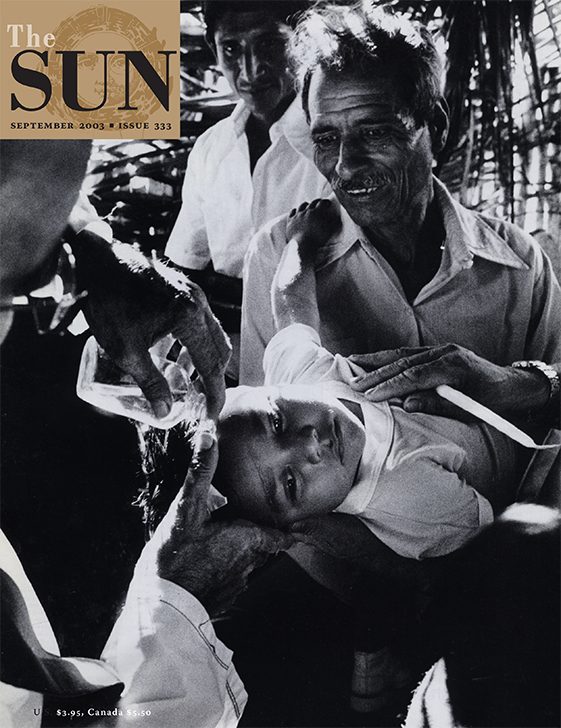

I am in Room One, the first on the left at the top of the wide marble steps, with the rest of the first-graders. The mothers are beginning to leave. A lot of kids are crying. It still has not occurred to me to be afraid.

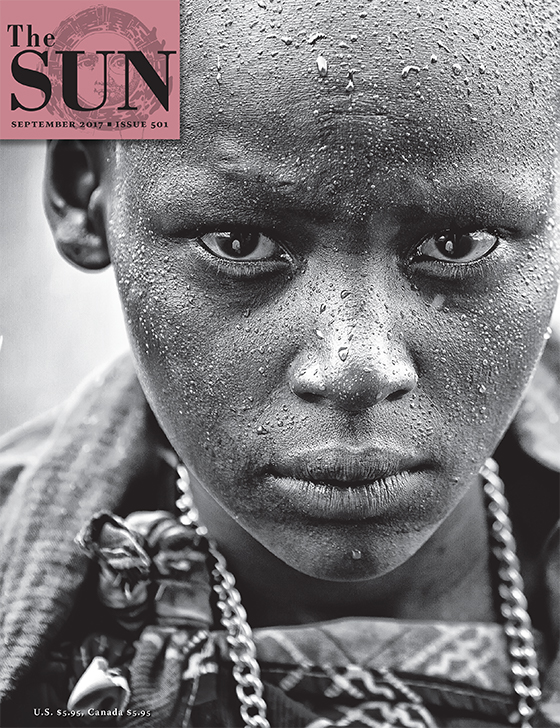

One girl grows hysterical — trying to twist out of her sweater — as a smiling nun pulls her away from her departing mother. The more composed children sit at their desks, stock-still, hands folded on desktops in front of them. I stare at a haggard, spindly, ascetic little girl in profile against the mighty sycamores outside the windows. She is so still, she seems to be trying to disappear. Her skin is like paper; her face is white; her eyes are black marbles stuck in her face. I see the rapt terror in her blue-veined tininess.