The wheat is starting to turn, flashes of deep gold streaking through all that tall, waving green. Before we moved to Colorado, I used to think wheat grew golden yellow, like in all the photos I’d seen. I suspect most city folk think that. They don’t realize that wheat grows up green and living and then dies, and that’s when it becomes useful.

This wheat will be harvested next month. Dry weather is good now because there can be only 15 percent moisture in wheat when it’s harvested. Not every girl knows that. But I’m learning everything I can, because this time, my parents say, we’re staying.

My brother Bill’s not looking at the wheat, though. He’s staring straight ahead, one arm draped over the steering wheel, trying to look cool. He’s not driving as fast as he was. His face is still red, but the slap mark isn’t visible anymore; it’s disappeared into the rest of his cheek. There’s a wet line running down his face, but it looks like it’s drying quick. It’s just like he says: if you wait, things will always get better.

As if to prove it, Bill says, in a happy voice, “Well, he sure surprised us this time, didn’t he?”

“Yeah,” I mumble. My voice sounds too quiet, so I say it again, louder: “Yeah, he sure did.”

“Dad’s just having a bad day,” Bill says, and he nods, agreeing with himself.

But then a new tear starts, and I know he doesn’t want me looking at him, so I stare at the old .22 rifle resting on the seat between us. Just last week, Bill was trying to teach me how to shoot it. I didn’t come close to hitting any prairie dogs, but we had a good time, laughing hard, and that makes me smile.

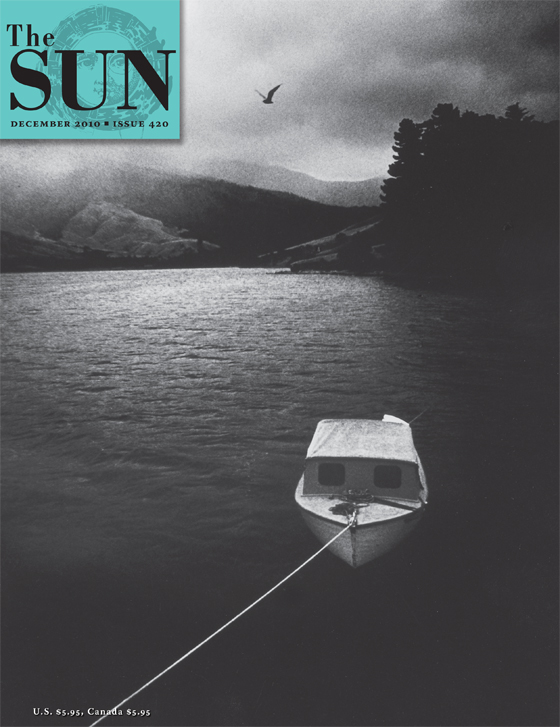

Now we’re on County Road 14-L. Up ahead is Baxter’s windmill and water tank and cows. The wind is rushing in the windows. We’re almost to our land, a quarter section: 160 acres. Sometimes I think if we lose this land I might die. I don’t even take the quarters and dimes off the dryer anymore; Mom and Dad might need them to help with the payments. So I just let the money sit, because I want us to build a house on this land and move here, just like they say we will. I want to live on this prairie that stretches and stretches, expanding so far into nowhere that nothing can stop it, not even the soft purple mountains in the distance.

Bill parks the truck, and there it is, our land, spreading out before us, pale and bumpy, rolling and curving its way to the horizon. Someday our house will break up this view, sitting in the middle of all those trees we just planted. Four rows of Rocky Mountain juniper arranged to form a box, a hundred trees in each row. They’re still only about two feet tall, and they grow slow, but they’re drought-resistant, and that’s what you need in this place. We spent most of last summer planting them — marking off rows, digging holes, putting in special pellets to hold moisture, planting each little tree, and then hauling up all that water every weekend to help get them started. Each time I poured some water around a tree’s roots, I’d imagine it was smiling and lifting up its little needles to hug me. A 60 percent survival rate is good, Dad says; we shouldn’t hope for more than that. But they’re all looking good right now, if you ask me. I can’t wait for them to circle us someday — circle us and protect us.

I jump out of the truck, walk over to the closest tree, and bend down to feel the little needles. The new growth is soft and green against the dark, brittle older needles. The trees themselves seem young and alive next to all this sagebrush and yucca and prickly pear cactus. I hear a faraway meadowlark, and I stand up and stretch and stare at the turquoise sky.

From the truck, Bill calls, “What’s that?” My eyes follow in the direction his arm is pointing. There in the far distance, all by itself, is a rust-colored animal. It could be a cow, except it’s standing all wrong. Its shoulders are high, and its butt is down low.

“Looks like a baby buffalo,” I call back.

Bill climbs out with the rifle and says, “Let’s go check it out,” and he takes off.

I have to move fast to keep up, running way past our trees and scrambling through the barbed-wire fence that separates our land from Baxter’s. He’d be mad if he knew we were on his land, because he’s an ornery old grump, liable to shoot just about anyone, I hear. That thing up ahead must be one of his calves. I can see its white face and reddish brown hide, like a Hereford. But it looks like it’s sitting down.

Bill stops running and looks back at me. “I bet its leg is stuck in a prairie-dog hole,” he says. “Come on!”

He takes off again, and I’m left catching my breath. But I don’t want to be just standing here where a rattler might get me, so I start running again. I’m watching the ground for snakes so closely I almost run into Bill, who’s stopped short, blocking my view. I hear the calf bawling, and Bill whispering, “Oh, Jesus. Oh, damn,” over and over.

In front it looks like a regular calf — long eyelashes, dirty white face, soft pink nose. But its spine curves down because its back legs aren’t the right height. All it has are two round stumps covered in a dark, sticky blood. There’s nothing below the knee. No little hooves, no thin ankle. Nothing.

The calf bawls again, then takes a pitiful step away from us, limping on its two front legs and dragging the bloody back legs behind.

I try to pull Bill away. “It’s one of those cows that’s been mutilated by a UFO!” I say.

He jerks his arm free from my grip and says softly, “You read too many space books.”

“Then how’d it get that way?”

“I bet the back legs froze after it was born this winter, and Baxter chopped them off at the knee.”

“Nobody’d do that, Bill.”

“Yes, they would.”

“No.”

“I’ve heard of worse,” Bill says, a hard look in his eyes. “I bet Baxter’s just hoping it lives long enough to gain some weight. Then he’ll make more money when he sells it for butcher. Look, you can tell the wounds are old: there’s some hide grown over the stumps, but it keeps ripping away. I bet it’s three months old.” He bends down and looks beneath the calf. “It’s a little heifer.”

“A girl?” Even though I don’t want to, I start to cry pretty loud. “But why’d he do that, Bill? Why didn’t he at least keep her up at his ranch and feed her?”

“ ’Cause he’s a mean son of a bitch.”

“I don’t believe you. He wouldn’t leave this calf out here. Not if he knew.”

Bill reaches out and touches my shoulder like he’s sorry to have to tell me this: “She’s tagged,” he says.

Sure enough, the calf has a yellow tag hanging from her ear: x16. She turns her little white head as if to show it to me, as if to say, “Who did this to me? Why do I hurt so much?”

I want to hold her, to tell her I don’t understand either. But if I move toward her, she’ll only take another painful, bloody step away, because she’s afraid of me.

Bill’s crying and fiddling with the .22. “Yep, if she lasted till weaning time, she’d bring a few hundred bucks. But now she’s wandered too far from the windmill, probably trying to follow her mama. The cows went back, and she couldn’t keep up. Maybe her mama will come back, maybe not. One thing’s for sure: she’s dying of thirst.”

The calf bawls softly when he says that, like maybe she’s agreeing. Then she folds her front legs and lies down on the ground and stretches out on her side. Her little belly heaves, and her tail twitches. Some flies rise up, then settle on her again. Pebbles and dirt are matted in the bloody hair on the base of each stub.

She doesn’t look up when Bill slides a bullet into the chamber with a click. She just lies there, breathing. Even when Bill raises the rifle so that the barrel is pointing right at her head, she doesn’t move.

“You could get in a lot of trouble, Bill.”

“Yeah,” he says, and unlocks the safety.

“Baxter knows she’s out here.”

He turns his head to look at me, but keeps the gun raised. “Yeah, he does.”

And I don’t want to keep looking into his watery eyes, so I look at the calf, her silky, soft hide surrounded by yucca and cactus and dry grass. With each breath, her side heaves, and the dust in front of her pink nose springs into the air. An eyelid blinks slowly across a dark eye. I hold my breath and watch the puffs of dirt rise from beneath her nose.

Bill lowers the gun. “I can’t do it,” he says.

Before I know it, I’m hitting him and screaming, “You do it!” My fists are tight and my punches are hard and Bill pushes me back and I fall into a yucca and scrape against the barbs and scream and as I’m standing up the shot crashes and I feel the waves of sound splinter through me. Then everything’s silent. Even the meadowlark has stopped singing.

Beneath the calf’s nose, there’s blood streaming onto the ground, dark and thick.

We’re running back to our land, toward our small trees. We fly through them and the tops graze our calves and scrape against our knees. Finally we stop and I’m trying to breathe but I can’t, because I’m crying and tired from running so far. Bill sets the rifle on the ground. He’s crying, too, but he comes up and hugs me and I breathe in his warm smell and press my forehead into his shirt. I want to stay like this for a long time, protected by his arms, but all of a sudden he jerks away and kicks the ground, then raises his foot and stomps down on top of a tree, twisting his toe to grind the brittle needles into the ground. Then he reaches down and pulls at the tiny trunk and the tree comes up, followed by thin, curly roots and sandy grains of soil. He throws the tree down as hard as he can. I want to scoop it up and nestle it back into its hole, smoothing the dirt up around it, but something stops me. Lying in the dirt, the tangled roots are already starting to wilt in the sun.