The Beast in Your Head

Read an Essay from an Upcoming Issue

By Cynthia Marie Hoffman • February 22, 2024I confess that I had never listened to Metallica’s “Enter Sandman” all the way through until I read “The Beast in Your Head,” but that didn’t keep me from being drawn into Cynthia Marie Hoffman’s reflection on how the song informed her experience as a teenager with undiagnosed obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). I admire the way she weaves the song through accounts of both childhood trauma and adult joy.

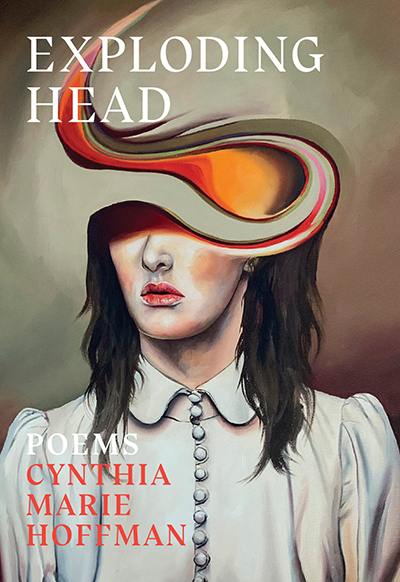

We’ve scheduled “The Beast in Your Head” for an upcoming issue of the magazine, but we’re sharing this essay early online in celebration of Cynthia’s new memoir in prose poems, Exploding Head, published this month by Persea Books, which further explores the ways OCD has affected her life.

Take care and read well,

David Mahaffey, Associate Editor

The last thing I saw before the accident was the windshield full of trees.

It was two nights before my junior year of high school, and I was doing the kind of rock-hard thing the youth were doing in northern Virginia in the nineties at midnight—driving the winding roads of Clifton deep into the forest to stake out an abandoned building rumored to have once been an insane asylum.

I was with an older guy and his group of friends. They were part of a CB radio club, and the driver’s handle was Death Driver. He drove like it, too, going flat out in his mom’s hatchback. There were seven of us in that car: two in the front, me and my date in the middle, and three huddled cross-legged in the back. The CB radio crackled with static: Come in, Death Driver. Metallica’s black album blasted from the tape deck. None of us were wearing seatbelts.

Metal was my identity in high school. The girls wore ripped jeans and silver crosses, and our friends were the boys with long hair and leather jackets. We clomped down the halls in our Doc Martens, divining ourselves future rock stars, and I took it seriously. I took music theory and choir, sat first chair in the ensemble on classical guitar with one foot perched on a footstool. I performed in a button-down shirt, slicked my frizzy hair flat as possible, caked my blushing cheeks in thick concealer. At home, I slung my Ibanez over my shoulder by its leather strap. I had all the TAB music books with their power chords and tough-looking guys on the covers, arms crossed. I knew I would never be that confident or wild. I was afraid all the time. I was afraid of everything around me and also myself. But in my room, alone with my guitar, I could pretend.

During the day, in the classroom, it often occurred to me that I might stab myself in the eye with my mechanical pencil. Eyeballs seemed to me the most delicate of membranes, as easy to puncture as pressing a straw through the meniscus of a glass of water. Gripping that pencil in my fist, trying to pay attention to the lesson, careful to shade the correct ovals on the Scantron, I saw the pencil rushing toward my eye with its silvery graphite point. Each moment ticked past in which I could have done it but didn’t. Each moment led to the next in which I might. What if just thinking about it made me do it? In my forearm, a muscle twitched.

I didn’t feel safe. It wasn’t just the pencil. I saw the tiles exploding from under my feet in the hallway. I saw the slim blue locker doors blowing off, the bodies of my friends sliced by the suddenly hurtling swords. On the road approaching cars jerked at the last moment head-on into my car. I saw the twisted metal, smoke rising from the hood. In the parking lot every car that crept past rolled down a window, presented a gun, and shot me in the arm.

The only thing that offered any relief was counting. Looking at the four sides of the chalkboard in a particular order was oddly comforting. It kept the pencil firmly in contact with the paper. But sometimes even the counting scared me. I had to keep doing it far past the point of comfort, bouncing from right to left, top to bottom, one two three four, faster and faster until I felt a burning irritation in my brain, and it was hard to concentrate on dissonance and diminished scales in music class. All I could manage was the 4/4 time signature building in my head in a measured accelerando, a guitar solo speeding faster than my fingers could keep up, a car headed straight for a tree with my own lead foot on the pedal.

Why was I like this? In my heart I felt like a kind person, a sensitive person. But I must have been, at my core, attracted to violence. Why else would I constantly think about stabbings and car accidents and explosions? I knew I couldn’t tell a soul. In a way, in my chunky boots and thick silver crosses clanking at my chest, I was hiding in plain sight. I was fronting like I was comfortable with who I thought I was. Even though it scared me, I could handle it. I was on my own, so I had to handle it. And even if I’d wanted to tell, what could I have said? I had never heard of “intrusive thoughts” or “compulsive rituals.” I didn’t have the language to name what was happening to me. But I still had to hold the pencil. I had to keep writing, do well, keep my head down.

Metallica’s black album dropped in August of 1991 when I was sixteen years old. The video for the first single, “Enter Sandman,” hit MTV earlier that summer, and I sat in my basement, hearing that song for the first time, glued to the screen. The opening six-note arpeggio guitar melody is immediately ominous. It lifts and falls back again. For eight bars, you have the sense that something is creeping up behind you. And then a layering of drums builds louder and louder, multiple distorted guitars join one by one, sharing a driving riff, and then with a leaden boom, finally slurring into a thick, monstrous groove.

On the screen, a boy is drowning at the bottom of a pool. The band plays in a dark room. The boy falls endlessly through darkness. Something’s wrong, the lyrics shout. He flails in bed with nightmares. Dreams of dragon’s fire / and of things that will bite. He’s chased off the road by a truck and tumbles down a ravine. He falls from a tall building, arms waving. Exit: light / enter: night. The guitar winds down until it’s just the drums. James Hetfield and the boy recite a call-and-response prayer. Then: It’s just the beasts under your bed, / in your closet, in your head.

This is me, I thought. I had heavy thoughts. I had a beast in my head, and no one knew but Metallica.

I rushed to buy the black album, popped the cassette into the tape deck in my car, and listened on repeat. When it was done, there would be a long silence, a whirring sound while the tape rewound to the beginning, and then it would start all over again with the first track, “Enter Sandman,” those opening notes like something creeping up behind me in the music. And then the build. And then the groove.

One night, my girlfriends and I turned up “Enter Sandman” on the stereo in the basement. We pretended to be metalheads, we were metalheads, standing on our pillows and sleeping bags, mocking furious faces at each other but headbanging for real, the way the guys did it. The propulsive drumbeat kept us synchronized. Metal was the puppeteer lying in its grave beneath our feet, its strings drilled straight into our foreheads. True headbanging metalheads took their bent-over stance in a wide lunge, air guitar in hand, nodding toward death. They banged their heads so much they grew sweaty, and their long hair clung to their faces in clumps.

In a short time half of us collapsed to the couch laughing and lightheaded, but the other half kept at it. I kept at it. For the length of that song, in the safe circle of my pajamaed friends, I let out all the fear and anger and rage I’d been holding in secret. I flung my stupid, frizzy hair and let its brittle ends rub my cheeks until I didn’t feel my body anymore. Until there was no distinction where the edge of my human form met the edge of the music. Metal was violent, I was violent, and this was who I was meant to be.

Toward the end of the song, there’s a sinister laugh. And then a vocalized boom to match the drums—an explosion on impact.

There were no lights on the thin road that bent through the forest in Clifton, so the only thing I could see from the back seat as the seven of us sped along in Death Driver’s car was whatever filled the oval of light from his headlights—a curve of road and the gray trees rising from pools of darkness on either side.

He was speeding so fast I thought for sure we were going to die. This fear was different from the fears in my head. This fear was so real I could taste it. It was in my mouth. I screamed at the driver to slow down, but he didn’t slow down. He didn’t acknowledge my screaming over the volume of Metallica blasting from the speakers. In fact, I think my screaming egged him on. It became part of the frenetic music of the car. My voice and James Hetfield’s voice together full-throating our fears into the night.

And then we started swerving across the double line, back and forth, up hills where the headlights beamed into the canopy of the forest, leaving a pocket of darkness below, an open mouth from which an oncoming car could spit forth at any moment. I clutched the driver’s seat in front of me, bracing for impact. But each time, the car settled back onto the road, and we sped downhill again.

And then there was nothing in the windshield but trees.

We sailed into the pit of darkness beyond the road. It seemed to last forever, that sensation of weightlessness when your stomach lifts inside your body. I felt my body lift inside the car, and I felt the car turning around me. For a moment I was an astronaut, floating steady, upright, while the spaceship rotated around me through the blackness of space.

And then we fell.

The music cut off instantly, taken over by the crunch and squeal of car metal, the cracking trunks of trees, the jostle and thump of human bodies.

The car ended up mostly upside down. I ended up with my stomach on the ceiling, a metal bar pressed against my hip. The silence was louder than any music. I couldn’t hear my own breathing, but I knew I was alive. I could see directly out the shattered window, and I started to wriggle my body toward the opening. Then, as if from a great distance, came a moaning sound and a whirring sound. Moaning from my fellow passengers. Whirring from the tape deck: Metallica’s black album rewinding.

I climbed out the window and over the car. We must have scrambled up the side of the hill, because suddenly all seven of us were there, standing stupefied in the road. We looked back at the belly of the car lying in the ditch, headlights still on. I don’t know how, but we all walked away. One of us bleeding from the head, another’s forearms glittering with embedded glass, we set off to get help.

We had walked just a few yards down the road when the tape finished rewinding in the deck of the car and that familiar haunting guitar from “Enter Sandman” returned, blasting full volume from the ditch. When Hetfield sang, Exit: light, / enter: night, I thought about how this had almost been the end; this had almost been our lights out, off to never never land moment, inside that crushed metal tube. But instead we were dragging our own legs one step at a time away from the scene of the accident until the music was just a distant thumping in the forest, perhaps some other group of kids having a late-night party on one of the last nights of summer before school.

For days after, my body ached. I started my junior year of high school in pain. For months, every night I shut my eyes in bed, I saw the flash of trees. For weeks a sickening weightlessness lofted in my chest. I was that boy in the “Enter Sandman” video falling endlessly through darkness. Every moment was the moment just before impact. When I fell asleep, I was in the car again, falling into that black ditch, and my body jerked awake.

Something changed after the accident. For the first time, something truly violent and terrifying had actually happened to me. It wasn’t an intrusive thought anymore. It was a memory. And I didn’t feel like I’d expected to feel—neither powerful nor brutish like the guys in the music videos. What had I thought when I’d looked up to those metalheads growling and smashing guitars? Had I believed that by performing violence, they had acquired some mastery over it? And that if I looked tough like them, it would mean I, too, had control over the things that scared me?

The accident made clear that no matter how much I’d dressed like them, or played guitar like them, I was just as delicate and afraid as ever. Black jeans and power chords, even a scowl on my face, hadn’t prevented a violent accident from finding me. Nor could I credit my furiously counting patterns on the chalkboard, like a protective magic, with having prevented bombs from going off at school.

And when violence found me, metal didn’t make me cool with it. How could this be my true identity if it scared me so? Now that I’d confronted violence head-on, I understood with new clarity that I would never turn the steering wheel purposefully into an oncoming car, even if I couldn’t stop thinking I might. I would never, ever stab myself in the eye. I wouldn’t wish any of this on anyone, even myself.

That was the beginning of the end of metal for me. Metallica’s music had become synonymous with nightmare, and I was losing my taste for music that fed the beast in my head. I wanted to forget. Bit by bit I fell out of love with music. The grunge scene came and went. I dabbled in classic rock, acoustic, in search of something gentler. But if I wasn’t glorifying darkness, I didn’t know what to replace the darkness with. Halfway through college, I laid my guitars inside their velvet-lined coffins, snapped the latches shut, and buried them in the back of the closet. I became the person who used to love music. The ex-metalhead. Exit: Sandman.

The thing about OCD is it’s suspicious of joy. The violent thoughts still slip their way into my mind, twenty-five years later, and I have to stay vigilant, counting the sides of the window frame or tapping my fingers to my thumb in a pattern until I get it precisely right. Joy is ephemeral, untethered. But OCD is about control. If I break my concentration from worrying, I won’t be able to count to seven and stop the oncoming car from hitting us or the plane from falling out of the sky. It’s like living perpetually inside the first eight bars of “Enter Sandman” with that guitar melody building and building, the distortion of OCD creeping up from behind.

The spring of 2022, I got hooked on the singer Adam Lambert. I downloaded his entire catalog, starting with the funky seventies-throwback grooves of the Velvet album and working my way back through the glam rock and club beats of his earlier recordings, his decade of magnetic performances as the front man for Queen, and back to the days I’d first seen him appear on American Idol. His vocal control was better than any metal screamer. And instead of lyrics like Metallica’s I’m your hate when you want love, Adam sang, Tell a stranger that they’re beautiful / so all you feel is love, and, I’m gonna take back my superpower.

I blasted the songs as I drove to work or home from some mundane midlife shopping trip, rear seats stacked with cat litter and paper towels. Though I could never hit the highest notes, I tried. And I laughed at myself while trying. Who cared? I was alone in the car where no one would hear. Lambert’s music videos often have an element of camp, a bit of self-mockery. They suggest to me that the secret to confidence, perhaps even the secret to joy, is the ability to not take yourself too seriously. OCD takes itself very seriously. But I didn’t want to embrace the darkness anymore.

Bit by bit, I was falling in love with music again. I got the twelve earrings put back in my left ear, which I’d pierced in high school. I had taken them out when, at some point, I thought I’d gotten too old to be edgy or creative with how I looked. When I walked through the door with my ear full of metal again, my husband said, “Welcome back.” Once the piercings healed and I fell again into the familiar habit of cupping my hand to flatten the silver hoops against my ear, like the gesture of someone who’s really trying to listen, I felt reacquainted with a part of myself I’d put aside long ago.

By the end of summer I had tickets to see Adam Lambert perform a Halloween-themed concert in Las Vegas. And in late October I flew across the country—husband and thirteen-year-old in tow—to make my pilgrimage to the source of the joy I’d been courting for months. I had to see what camp Lambert was all about.

The night of the concert, I wore a sequined jacket that was sold as a “glitter bomber” in oceanic mermaid colors. As we stepped from our hotel room into the hall, my husband stopped to take my picture with the shimmering wave of light my jacket splashed across the door.

Camp Lambert was theater and costume. The show opened with two male back-up dancers dressed in hooded cloaks and carrying sage that left behind a trail of smoke—a cleansing or conjuring, maybe both. And when Adam walked onstage, the crowd became a roiling sea, an energy that rippled through the room, lifting me as it passed. I felt it zing through my husband and child, too, as we touched shoulders.

Adam’s voice was just as powerful in that room as it was in the studio, perhaps more. He wore a glittering cape and wide-leg pants that glinted with what looked like bits of shattered glass, bedazzled by the front man himself. He told us so between songs in a speech delivered more like a stand-up comedian than a rock star. “I want to tell you how deep I got with the glue gun,” he joked. “We’re really close.”

There was choreography, vibrato, heels. I knew the words to all the songs, even the cover songs sprinkled in, and I sang my part in the chorus, buoyed by strangers. And a part of me—the part that was smiling with a sparkly-eyed, undoubtedly goofy look on my face—felt sort of dumb. What had I been doing with my life all these years by shutting out anything that wasn’t fear and gloom? Why had I believed the violent intrusive thoughts represented a truer version of the world than this one? When here it was, all this time: Dancing! Glitter! Available to me.

Adam flicked his cape as he turned.

And then he left the stage for a costume change. The lights went out. My husband and child dissolved into shadow. The crowd hushed and shuffled its feet. And when the guitar sliced through the darkness, it was a familiar, ominous melody.

I was transported to that night long ago, terrified and shaken and walking away from the scene of mangled metal turned over in a ditch. I was that child again who ruined everything with her fear. It was so easy to let the beast slip back in. A familiar anxiety pricked my skin. I was anxious about all the things anxiety had taken from me, and now I felt it coming to take away even the tentative levity of this night. I became acutely aware that the stage was a four-sided thing. I started to count. Perhaps I would never walk away unscathed from “Enter Sandman.”

The bass drum kicked in, and I was still bracing for impact when Adam reappeared in a red kilt and devil horns adorned with sequins. The crowd erupted in delight. The guitar slurred into the groove. Adam shouted, “Welcome to hell, motherfuckers!” and flashed a wide white grin.

We all laughed. I laughed. This wasn’t hell. This was Adam Lambert’s version of hell. It was metal, but sparkly.

There was no guttural Hetfield growl, no Grim Reaper puppeteer pulling Adam—or us—into the ground. The song sounded good in his glam-pop voice with its vocal runs and effortlessly belted high notes. Different, but good. Adam sang upright and lifted through the chest. He couldn’t have banged his head much without impaling a cheek on the metal spikes mounted on his football shoulder pads. Even his ridiculously tall platform boots conspired to float him six inches above the ground.

As I listened, really listened, I started to let go of the accident. I let the magnetic chaos of that moment lift me in its beam of light off that road in the late summer of 1991 and deliver me back here, to this alternate universe thirty-one years later, with my husband and teen firmly beside me. I felt the nostalgic propulsion in the beat. A twisting wrench of reinvention. And I found myself, along with the crowd, banging my head. Not the kind of headbanging from years ago in the basement; this was more of an emphatic nod, a nod like hard-rock church. Adam winked. Whatever this was, we were all in on it.

The ending notes of “Enter Sandman,” which I’d learned to play on guitar, are the same notes as that ominous opening riff, played in reverse. As the song fades out, it must play out its inevitable opposite; written into its very fabric is its own undoing. That night, Adam could have sung the lyrics backward, and it would have made perfect sense. Something heavy was lifted out of me. The beast was still in my head, but I let go of my vigilance. At least part of me knew the concert hall would not explode if I allowed myself to forget. A car would not come crashing through the wall. At least a part of me accepted that I could have joy. Senseless, wacky joy. Even when confronted with this song that would perhaps always haunt me, this theme song to the darkness I’d been carrying all these years.

Sometimes joyful music still feels foreign, even scarier than the thrashing and violent parts of myself I know so well. But I’m going to keep listening.

CYNTHIA MARIE HOFFMAN

Cynthia Marie Hoffman is the author of four poetry collections: Exploding Head, Call Me When You Want to Talk about the Tombstones, Paper Doll Fetus, and Sightseer, as well as the chapbook Her Human Costume. Her poems have appeared in Electric Literature, the Believer, the Los Angeles Review, the Missouri Review, and elsewhere. Cynthia received her BA and MFA from George Mason University, and she has taught creative writing and composition at George Mason University, the University of Wisconsin, and Edgewood College. She works at an electrical engineering firm in Madison, Wisconsin, where she lives with her husband and teenage child.

Request a free trial, and we’ll mail you a print copy of this month’s issue. Plus you’ll get full online access — including 50 years of archives. Request A Free Issue