This child is not my own, but still the words of possession slip from me: “My baby girl. My sweet baby.” Although I’ve never seen her before, I think I know what she needs: the lights at her hospital bedside dimmed, her loose arms girdled securely against her chest. She has no name except “Girl” and a family surname typed on the identification card at the foot of her crib. It’s too early for her to have a name like Betty or Jennifer or Anastasia. She surprised everyone, caught her parents without a crib or a car seat, without casseroles in the freezer, without the stamina new parents need. I pat her back, shade her eyes, clutch both of her hands in my palm and hold them against her sternum. She relaxes and makes a sound — not a laugh or a sob, but something in between: a moist sigh of resignation. I coo back to her, and so we converse, our rudimentary sounds vibrating the internal cord that governs reflex. Communication on the infant ward is reduced to this: She sticks out her tongue; I stick out mine. She blinks; I blink. She gurgles, and so do I. She cries, and my voice veers up in commiseration: “Yes, I know. Everything’s going to be all right.”

Of course, I know no such thing. I know nothing about her except her immediate physical needs and desires. I don’t know which organs might fail, or if there are gaps that weaken her heart, or where her parents might be. I’m just a volunteer: every Wednesday I put on a blue jacket with a name tag and hold babies for three hours. “I’m just a volunteer,” I say when a parent asks me about medications, or when a doctor arrives to pass his flashlight across a baby’s face. That “just” modifies me; I am a presence as inconspicuous yet necessary as a ceiling tile or a light.

I know nothing, so in lieu of knowledge I cultivate instinct. I slip through the halls, nearly invisible, drawn by a baby’s cry someplace on the floor. I snap on latex gloves and thread my arms through a tangle of IV lines to lift the child from her crib. I back into a rocking chair, by now an expert at holding the array of tubing aloft, hardly noticing anymore the bandages, the bruises, the cuts. The baby promptly falls asleep in my arms, but I go on rocking and rocking. I can’t put her down, not yet. The rocking reminds me of the davening of Jewish men at the front of the synagogue: the repeated half bow to an unseen presence, the bodily gesture of prayer. I know she feels me rocking, even in her sleep. Her breath — sour and bitter — becomes my breath, her stuttering heart my own.

Another baby stays awake, gazing at me and wondering. She blinks slowly. Her fingers tug at the oxygen tube in her nose. Her pupils expand slightly when her eyes alight on my face. Three different IV bags dispense liquids drop by drop, the tubes converging into a single needle that pierces the back of her hand, held in place by a padded splint. A nurse beckons to me, so I lift the child back into her crib, place her on her side, and tuck a rolled blanket against her back. I watch her a few seconds more, my chest already cool with her absence. If she’s lucky, we’ll never see each other again.

The nurse asks me to help pacify a distressed preemie. I slip my hands through the gloves in the incubator and stroke a stomach the size of a newborn kitten’s. He’s crying, but I barely hear him through the plastic walls, and he soon settles down. His arms lie open at his side; his mouth shapes itself to an imaginary breast.

Around me, the infant ward projects an aura of stability — no emergencies here, no alarms. One floor above us is intensive care: many of the babies here have descended from that plane, returned from the brink, their parents exhausted and pale. One floor below is the emergency room: other babies have ascended from there, rescued from seizures, choking, concussions. Sandwiched between those floors of panic lies this realm of equilibrium, where every breath is monitored, every pulse. Nurses slip from task to task, swaddling babies, stripping paper off thermometers, writing every observation in their charts. These actions merge into one, lulling me into feeling that all here is business as usual, and nothing could really go wrong.

But in one of the isolation rooms, a child is screaming: a little girl, two days old, born with no anus. “She poops out the same hole as she pees,” the nurse cheerfully tells me, in case I need to change her. I sit in a rocking chair and hold the newborn as she grimaces. I can’t help but become acutely conscious of my own body: my colon, my vagina, my rectum. I imagine how easy it is for something to go wrong, for the parts not to match up completely: one small error, and a lifetime of pain, discomfort, complications. Maybe not even that. Maybe not a lifetime.

Sleeper couches fold out next to each crib, and often the floor surrounding them is cluttered with overnight bags, magazines, and snacks. Inside the cribs, Polaroid photos of Mom and Dad hang at eye level, crayon drawings by siblings chirp, “I love you!” and colorful handmade blankets are tucked into corners.

I sometimes wonder what I would do if my baby were in a hospital crib for three months, attached to a monitor to make sure she was breathing. Would I have the stamina to sleep in one of these white leatherette chairs every night? Would I walk outside under the cherry trees that blossom along the drive of Children’s Hospital? Would I keep walking on and on, gulping the fresh air, trying not to scream? I want to believe I would be at the bedside every minute, holding my child against my belly. But yesterday I had a splitting headache, and I wanted nothing more than to put down the fussing baby at my shoulder. I wanted nothing more than to be unburdened beneath the cherry trees.

When I was twenty, I had two ectopic pregnancies, which left me unable to bear children of my own. The fertilized eggs had grown in my fallopian tubes and burst the narrow ducts. After both miscarriages, I woke in a hospital room feeling not only the pain in my groin, where bandages held me together, but a vague sense of guilt, as if l were being punished for some terrible, unnamed transgression. I wasn’t a religious person, having grown up in a casually Jewish household, but I went to the Hebrew Bible and read about the barren women — Sarah, Rachel, Hannah — whose stories confirmed my fears: infertility was a deliberate curse, an act of God, who “closed up” the wombs of inadequate women. Conversely, bearing children was a blessing — an opening and an absolution.

When I first learned I couldn’t have children, I tried to redeem this loss by thinking I could now mother all children, become a kind of everyday saint in my nurturance. Sometimes, as I rock and rock with these babies, I feel myself approach such an ideal, my individual body effaced by these ancient, maternal gestures. But more often, I look around the ward and feel only cranky and useless, overwhelmed by the infants, so many of them nameless and unwanted, their eyes shut tight against the world. These children wear hospital-issue T-shirts and are wrapped in plain flannel blankets from the ward shelves. Their cribs are blank, the only decoration an identification card and a densely scribbled chart — no balloons, no photos, no drawings. Such a naked bed usually signals that the child has been abandoned, left to the care of the hospital or the systems that exist to attend to such infants. The parents cannot be found, or refuse to come, or are under arrest.

Today I walk by an isolation room where the identification card on the door reads: “Doe, Jane.” Beneath the card is a green slip of paper asking the parents or guardians of this child to come to the admitting desk and fill out the requisite paperwork. I know this means the parents have disappeared. The shades are drawn, the door closed. I hover a moment but hear no cry, nothing to demand my presence, so I move on, my hands pushed deep into the square pockets of my blue jacket.

In the next room is a baby girl born too early, at thirty weeks, to a teenager who received no prenatal care. The baby’s bones were so brittle that most of them fractured during delivery. Now she’s almost blind, her lungs are malformed, her hearing damaged. Yet, two months out of the womb, she seems determined to live: she sucks on her bottle voraciously, tugging the nipple into her mouth, her eyes popping. The mother has not visited for three weeks, a student nurse tells me, and so I hold this baby closer and whisper in her ear, as if these few hours could somehow make up for a lifetime of neglect.

When I get home and tell my boyfriend about this child, about her medical problems and the absent mother, he responds, “Why didn’t she just get an abortion?” He has spoken my hidden thoughts, the ones I’ve tried to suppress all afternoon, and so I become angry and go out on the front steps and cry. When he comes out to apologize, I say, “That baby is not an abstract concept anymore.”

After my three months on the infant ward, the question of abortion has become more troubling to me, has sharpened into one essential question: When did the few divided cells inside that teenage girl become the baby whose weight I still feel in my arms? Certainly, the girl might have been better off choosing abortion; perhaps her child is destined for a life of trouble and pain. But is there really some threshold between nonhuman and human that is crossed at three months, or four months, or six? Does a fetus become human only when it starts to look like a person, with hands and fingers and hair? How do I explain the grief I still feel at my own miscarriages? The embryos were only four weeks old, but still I have the nagging sense that something — something human — has been irretrievably lost.

I have no answers, but I have too much time for such questions as I rock back and forth, a baby breathing rapidly in my arms. Some of them look as though they’re still in the womb; they’re that wrinkled and tenuous. I pat my hand rhythmically between their shoulder blades, mimicking an intrauterine heartbeat, giving them an overriding stimulus around which to organize the chaos.

Sometimes they stop breathing for a moment, and I panic. I nudge them a little, and their breath starts up again, smelling of milk. Their chapped lips twitch into the reflex of a smile.

The term “volunteer” derives from the obsolete word volunty, meaning “that which one wishes or desires.” You do this work because the desire comes to you naturally; if that impulse falters, you may stop, no questions asked. The volunteer tomatoes in my garden grow without any prompting from me; they arrive out of nowhere and are the hardiest plants, sticking it out long past the time when the other tomatoes have withered from drought or flood or disease.

We volunteers glance sideways at each other. We see the blue jackets out of the corners of our eyes and nod. We come here for different reasons, but our motives all look the same on the application forms: I want to give something back to the community. I love kids. I’m interested in being a doctor. Hovering behind those words are the other reasons: I’m lonely. I’m childless. I want to feel as if I matter. I want to be missed when I’m gone.

I don’t know if I’m missed when I’m gone. I get in my car and remove the blue jacket with the name tag. My hands still smell like baby, or of hospital soap and the talc-lined insides of latex gloves. My left arm will be sore for a day. I spend the rest of the week mostly working at my office, writing, going to the health club, and riding my bicycle through the city streets to the bay. Then comes Tuesday, and my schedule takes on a pleasing and necessary weight. “Tomorrow I’m at the hospital,” I say to no one in particular, marking it again on the calendar.

Yesterday, I held a baby who’d been beaten into a coma. I held her for three hours. Her body was unnaturally rigid, her cry like a cat’s meow. Her nerves could still respond to pain, the nurse told me, but otherwise her brain was inert. She was six months old. “Doesn’t look like she’ll come out of it,” the nurse said. She touched the baby’s head gently, then left me alone with her. The baby seemed most comfortable nestled tightly against my side, so long as I remained motionless; any movement startled her and made her cry. Once, she sucked her pacifier for twenty minutes, instinct bypassing the dead circuits in her brain. I memorized her eyelashes — deep black and impossibly long, curling against the ridge of her cheek.

I couldn’t help but imagine the moment a large hand had struck the soft spot at her temple, the impact, the crack of bone. I held her close in the crook of my arm and became rigid, like her, stiff as a catatonic. Hours later, when the nurses and I finally wedged the girl upright in bed, I saw her whole face for the first time. She was awake: one eye wide open, the other halfway closed. Her pupils were blank, her tongue resting dumbly inside her mouth.

After I left the hospital, I sat in my car and cried from exhaustion and fury. I drove home, my hands white against the steering wheel. My boyfriend said: “Perhaps you will be a blip on her memory, a second of comfort.” Perhaps. “You know how when you’re sick,” he said, “and all you remember is the hour a gentle breeze came through the window, cooling you? That moment of relief?”

More likely I’ll be nothing, or only a part of the continuum of pain. All that night, I felt the baby’s weight on my arm. I remembered stroking her knee, her calf, her toes already stiff, as if in rigor mortis. I remembered that one eye, open wide but focused on nothing. I could not reach her. While I stroked her, I’d tried to explain: This is what touch can mean.

I am there only once a week. I usually hold one baby, maybe two, sometimes three. How do these nurses bear it? And the doctors? I want to ask them, but they’re too busy. The babies keep arriving from intensive care and the emergency room. Like sponges, the babies absorb all of a family’s frustration, an entire community’s pain. They emerge, tactile evidence of abstract phenomena: here is the mottled face of poverty, the broken body of abuse, the hand of racism and inequity, bruised from the repeated probe of an IV.

Today is my last day on the infant ward. I’m moving to another city, and I’m going to miss these children more than I can say. A nurse, whose name I’ve never learned, has asked me to hold a little girl two months old, tiny as a newborn. This baby has a deep, phlegmy cough, so I wear a gown, gloves, and a face mask to feed her the bottle. She stares at me, astonished, grinning so much the nipple keeps popping from between her lips. To her, the world is all eyes looming above pink paper masks, and I can sense her trying to strip away these masks with the force of her gaze. She wears a hospital-issue T-shirt and socks that slither up her calves like leg warmers. No books, balloons, or drawings decorate her room. I see no name on her chart.

“Who are you?” I ask her, smiling under my mask. The nipple slides from her mouth. Her eyes are so bright I can hardly bear to look at them; they will burn me, I think, reveal all my fear and desire. But I lean a little closer to hear what she might say. Her arms windmill around her head — pointing to the cherry trees outside the window, to the other babies, to the nurses, and then back to me. She keeps her gaze steady on my face. “Who are you?” she laughs.

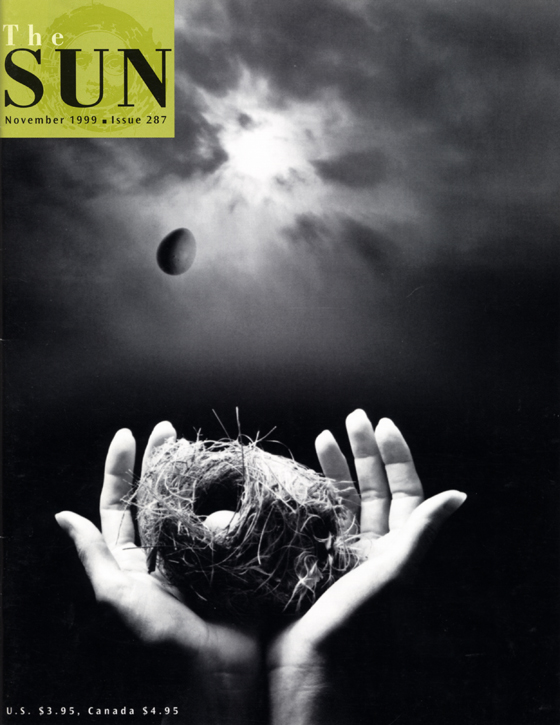

Who am I? I am a woman holding a baby not my own. I take her weight, light as it is, and hold her the way mothers will always hold infants: close to the breast, the heart.