Haiden’s morning sickness was bad, and she told me to get the boy out of the house, take him anywhere. She stood in the doorway of our downstairs bathroom, just off the kitchen, her frizzy black hair bound into a ponytail that pointed toward the ceiling like a squat exclamation point. “Please,” she said.

It was Saturday, the day I usually played racquetball with friends. I twirled my racket in her direction and arched my eyebrows. “Can’t you wait? I’ll only be gone an hour,” I said, teasing. “No more than two.”

From the living room, the boy, DeMarckus, mimicked the sounds of Haiden’s dry heaving. I imagined him kneeling over the coffee table, his chin scrunched into his neck. The coffee table was one of our projects from before DeMarckus had become our foster child six months earlier. Haiden and I had found the table at a garage sale, then stripped, varnished, and sandpapered the finish in spots to give it the appearance of age. Beneath the table’s beveled-glass top, we had placed a tea-stained map of the world. I listened to DeMarckus’s fake heaving and pictured the six-year-old’s face hovering over the bottom half of Africa.

Rolling her eyes, Haiden mouthed the words “Take him, Rick.” And then, out loud, she added, “Now. Like, any minute.” When I hesitated, she threatened me with the back of her hand, its cinnamon skin dry and ashy.

DeMarckus’s vomiting noises stopped, and he entered the kitchen and put a fist on his hip, considering Haiden. He was dressed in only a pair of backward underwear — his usual morning attire — and he tapped a bare foot on the linoleum floor and closed one eye. “Mama,” he said, shaking his head, “you look like you been stepped on.”

I tried to contain a laugh, wondering where the boy had gotten the line.

Looking ill, Haiden reentered the bathroom and shut the door. DeMarkus stared at the spot where she had been, stretching out his neck as if to gag.

“Go get dressed, Marcky,” I told him. “You and me are going to the pet store.”

He eyed the racket I still had in my hand. “For real?” he said. We had been to the pet store on a couple of Saturdays, but usually in the afternoon, after racquetball.

“Totally.” I set the racket on the counter. “And if you hurry, we can go get pancakes.”

In seconds DeMarckus was ascending the stairs two at a time, imitating Haiden, his pretend heaves interspersed with her words: “Please. Now. Like. Any. Minute.”

On Saturdays the animal shelter brought abandoned cats to the pet store in hopes of finding them homes. Just like every other time we’d been there, Marcky headed straight for the back corner of the store and began naming the cats after dead presidents. He probably thought he was naming them after elementary schools. The cages were tagged with the cats’ real names and a short explanation for their sorry situation, but Marcky couldn’t read, and even if he could, I doubt he’d have called the cats by names someone else had given them.

Hardware & Pets no longer sold hardware. The aisles that used to smell like fresh-cut lumber now had only that dirty-hamster-cage odor, and gurgling fish tanks lined every wall. I watched the boy poke his fingers through the cats’ cage doors. Most of the cats were unresponsive, still sleeping off breakfast, their tails curled at the tips like genie shoes. Marcky stopped at a cage labeled, SLIM: OWNERS HAD TO MOVE, and said, “Eisenhower. Eisey, Eisey, Eisey. Wake up!” The fat tabby opened one eye and then must have farted, because Marcky pinched his nose and turned to me in disgust. I plugged my nose in sympathy and made a face that said, Ewww.

“That was uncalled for, Eisenhower,” Marcky said, scolding the cat with his free index finger. Though his voice was nasal from the pinched nose, his tone perfectly mimicked Haiden’s. In six months of fostering DeMarckus, Haiden and I had rarely heard what the boy’s real voice sounded like. He was always imitating people — their inflections and cadences, long strings of their exact words. Some of his imitations were funny. He could do the bubbly clerk from the video store: “I absolutely love this movie. Really. It’s, like, my all-time favorite.” Or my mother, while we were watching a movie: “Isn’t there something more . . . I don’t know, useful we could all be doing?” Other times DeMarckus’s mimickry unsettled Haiden and me. Once, when I turned out the light after tucking him into bed, he said, “Oh, no. We don’t cut the fucking lights out in this house. We leave the lights on.” His voice was so cool and detached I thought there might be someone else in the room, but when I flipped on the light, I found only Marcky, angled across his bed.

I asked, “What was that?” in a voice that was equal parts anger and confusion.

Instead of answering me, Marcky said, “Thank you. That’s better.” Then he pulled the sheet over his shoulder and smushed his cheek into the pillow.

One night, before she became pregnant with Ben, Haiden had just dropped hot dogs in a pan to boil when she heard a snide voice from the bathroom say, “DeMarckus? What kind of name’s DeMarckus?” A feminine voice answered, “Maybe it’s a black-boy name. Because he’s a black boy.” Then an unchildlike voice said, “I’ll show you a fucking black-boy name, bitch.”

Haiden opened the bathroom door and found Marcky staring into the mirror, his backward drawers around his knees. He quickly hoisted his drawers and jeans, ran water over his hands, and left without flushing the small turd floating in the toilet.

Later that night, during dinner, Haiden asked Marcky how school had been that day.

“Cheese pizza,” he said.

Marcky often answered questions with non sequiturs about food. His favorite was “Applesauce.” Haiden assumed his peculiarities were caused by two things: one, his attention-deficit disorder, for which we fed him fifteen milligrams of Ritalin each morning; and two, the defense mechanisms he’d acquired during the years he’d spent with a negligent birth mother and in and out of questionable foster homes. At first Haiden had felt we should ignore it and give him time to adjust, but that night at dinner she persisted.

“What about the other kids at school?” she asked. “How are you getting along with them?”

Marcky, his hot-dog bun covering his mouth, whispered, “Green beans.” Then he rolled his eyes in feigned exasperation — an expression we found endearing — and added, “Applesauce.”

Unaware of what Haiden had witnessed earlier that afternoon, I raised my hot dog high like a scepter and said, “Applesauce, indeed.” I had expected the table to shake with laughter, but Haiden didn’t laugh; instead she opened her eyes wide, as if to keep from crying. Confused but still smiling, I turned to Marcky, whose expression perfectly mirrored Haiden’s.

In bed that night Haiden told me why she had been so upset. “And then you — you go and encourage him, saying, ‘Applesauce, indeed.’ ” She made a face and raised an invisible hot dog. “Do you think that’s wise, Rick?” she said. “Encouraging this?”

I had no idea. I wondered if she was worried about living in Woodhull. We’d bought a big two-story house there two years earlier and were one of about six black couples in the neighborhood. A few black children went to the elementary school, and before we’d brought Marcky home, we’d talked to their parents, who’d told us things were fine really. Not bad, anyway.

“The kids will adjust to Marcky,” I told Haiden. “And he’ll adjust to them.”

Haiden sighed and rolled onto her side, facing away from me. It wasn’t just finding him talking to the bathroom mirror, she said. It was more than that. There was something going on. “All that’s happened to that boy,” Haiden said. “The life he’s lived . . .”

“He’s with us now,” I said. “We’re the life he’s living.” My words hung over us for a moment, but Haiden didn’t respond. When I leaned over her to look at her face, her eyes were shut.

After Eisenhower passed gas, Marcky tapped the door of the next cage over, marked, EL NIÑO: HE WAS BREAKING HIS OWNER’S HEART. A scrawny Siamese at the back of the cage sat up and began pulling himself forward using only his front paws, his lifeless hind legs dragging behind him. “Roosevelt,” Marcky said, “what’s wrong, boy?”

It seemed uncannily intuitive of Marcky to name a cat that couldn’t walk “Roosevelt.” Another time he’d named an unneutered male with an erection “Kennedy.” Sometimes the boy appeared to just know things.

Roosevelt collapsed with the top of his head against the cage door. “Atta boy,” Marcky said. He scratched behind the cat’s ears with two fingers. “You like that, don’t you?” Roosevelt’s front legs stiffened. “Just don’t fart, OK, Mr. Roosevelt? Could you do that for me?” Marcky put his nose close to the cage and cooed, “I think you can. ’Cause you a good, no-fart kitty.”

Sometimes part of me forgot that he was a boy, a six-year-old boy, with a capacity for empathy — for love, even.

A pretty, college-age white girl in a tight T-shirt approached and stared at Marcky, admiring the way he interacted with Roosevelt.

“Do you want to get El Niño out of his cage?” she asked, a little too eager.

Under his breath Marcky whispered, “Pancakes.”

“He’s a very sweet cat,” the girl said. “I think we should get him out.”

Marcky turned to me and made a face like Can you believe this girl is talking to me? A few months earlier he would have scampered over and pressed his face into my leg. I was glad to see him hanging in there for a change, trying.

The girl placed a hand on Marcky’s shoulder. “Do you have any pets at home?” she asked.

“Hydrangea,” Marcky said.

The girl’s brow furrowed, and she looked at me. Haiden and I had a cat named Hydrangea, a fluffy white ball of fur we’d owned for almost our entire marriage. “Our cat’s name is Hydrangea,” I said.

The girl knelt so she was at eye level with Marcky, her palms on her thighs. “Let’s get El Niño out of his cage, hmm?”

Marcky tilted his head to the side and screwed up his face as if he smelled a dirty litter pan. Then he put his hand on her shoulder while she knelt before him, as if he were knighting or blessing her. “His name’s Roosevelt,” Marcky said, “and I don’t think that will be necessary.”

The girl stood, and Marcky’s hand fell to his side. “Well, wouldn’t you like to take Roosevelt home,” she asked, “so Hydrangea can have a brother?”

Marcky stuck his finger in his ear, twisted it, and whispered, “Butterscotch,” so low I almost had to read his lips. Then he added, out loud, in a voice that was all his, “Goodbye, Roosevelt. Goodbye, pretty girl. I love you.” And he walked past me into another part of the store.

“He’s a cutie,” the girl said. “How old is he?”

“That kid?” I said. “I’ve never seen him before in my life.” I chuckled to let her in on the joke, but the girl’s brow furrowed the way it had when Marcky had mentioned Hydrangea. I followed Marcky to find out where he’d gone.

About six weeks after Ben was conceived, Haiden and I sat Marcky down and explained to him that she was pregnant. I was worried about his reaction, but it turned out OK, about what I’d expect from a six-year-old: he walked over to Haiden, pointed a finger at her belly, and said, “You mean you have a baby in there?”

“Do you want to put your hand on my belly,” Haiden asked, “to say hello to the baby?”

Marcky looked at Haiden as if a horn were protruding from her forehead, and he began backing up. “No, thank you,” he said. “I don’t think so.”

A few weeks later, though, Marcky was talking to Haiden’s belly in the voice we were beginning to recognize as his, saying, “Remember, little brother or sister: pancakes are the perfect breakfast.” Or, “Don’t get mad when I get to stay up later than you. You’ll get to stay up late too when you’re older.” He was also calling Haiden “Mama,” and sometimes, after I’d read to him from the National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds — the kid loved birds — Marcky would call me “Dad,” and I would wonder at the strange sound of it.

But there was still the problem of those voices the boy conjured from his past — the years he’d spent in foster care and being raised by a mother who’d eventually lost custody of him and his two older siblings. Until we signed adoption papers, the caseworker couldn’t tell us where he’d been and what he might have seen before coming to us. We worried there was something predetermined about the boy’s fate, no matter how much love we gave him. Even Marcky’s innocent reactions — asking me, in his six-year-old voice, “For real?” or pointing at Haiden’s belly and saying, “You mean you have a baby in there?” — sometimes seemed like an act, as if he was merely behaving the way he thought he should.

I found Marcky perusing the dog toys not too far from the cats’ cages. Seeing me walking toward him, he pulled a five-dollar bill from his pocket, pinched the money at both ends, and snapped it twice in the air.

“Where did you get that?” I asked.

“Where do you think?” Marcky said. He huffed, and his eyes drifted toward the ceiling. “Mama gave it to me,” he said. Then he held the bill out to me and asked, “How much is it?”

I pointed to one of the bill’s corners. “You tell me,” I said. “What number does it have on the front?” The boy couldn’t read, but he knew most of his letters and all of his numerals. I guessed this was what parents did — they quizzed kids, to teach them.

Marcky disregarded my question and picked up a rubber pork chop. “Could I buy this?” he asked. “For Hydrangea. I think he deserves a treat. He’s a good —”

I took the toy from him. “I asked you a question.”

Marcky’s lips trembled, and he started to cry. “I was just trying to do something nice for the kitty,” he said.

The boy’s tears and attempt to play innocent annoyed me. Marcky would try this at bedtime, too, or when he wanted candy, and it was simultaneously artificial and sincere, the way it is when most six-year-olds cry, I imagine. I grabbed Marcky under his arm, and the five-dollar bill fell from his hand and floated to the floor.

“I asked you what number was on the front of your money,” I said, “and I would like for you to answer me.”

My grip on Marcky’s arm tightened, and I noticed the boy was on his tiptoes, real tears collecting in the corners of his eyes. I opened my fingers wide, and Marcky shrugged away from my grip and looked at the floor. In the kindest voice I could manage, I asked him to pick up the money.

Marcky bent to retrieve the bill, and when he righted himself, his tears were gone. “It’s a five,” he said. “OK?”

I wasn’t surprised by how quickly the boy had stopped crying, but I was caught off guard by the strange assurance in his voice.

“I want to buy Hydrangea something,” he said. “I want to spend all five dollars Mama gave me on Hydrangea.”

“That’s very generous of you,” I said, “but this is the dog-toy aisle. Let’s go look at the cat toys.” I put my arm around Marcky’s shoulder, and he pressed his head into my side.

“Yeah, yeah,” he said, “very generous of me.”

Haiden’s getting pregnant with Ben after Marcky came to live with us wasn’t something we’d planned. We had tried for three years to have a child — three years without doctors. Then, rather than seek a medical explanation for our difficulties, we’d registered to become foster parents.

Before Marcky came to live with us, his caseworker told us the boy was “SACY,” an acronym that stood for “sexually aggressive children and youth,” which she said didn’t mean that the boy was a preschool sex offender; he just knew more about sex than most kids his age. We had to notify the school when we registered him for first grade, and the principal said they’d had SACY kids before. They just had to keep an eye on him around the other students. Nothing out of the ordinary.

Haiden and I knew there had to be reasons for this designation, but those reasons were locked inside Marcky’s six-year-old head, and in a file his caseworker kept, which we would be allowed to access only after the adoption took place — if it took place. Haiden and I tried to find out what the boy had been exposed to, so we could know what we were dealing with, but the caseworker said the information was “sensitive.” It included police and psychiatric reports and the names of other foster parents and what had happened in their homes. There was no way, the caseworker said, that she could present that kind of information to people who might choose to maintain custody of the boy for only a day or so.

Haiden and I were OK with this at first; we didn’t think there was anything we could find out that would make us not want to take Marcky into our home.

And then Haiden got pregnant.

When we told the caseworker, she seemed almost alarmed. “OK,” she said. “There are ways to handle this. It isn’t anything to get worked up about.”

We hadn’t known that it might be, and all this secrecy was beginning to get to us. We asked just what was in that file. “Just tell us,” I said. “Let us know.”

Without giving any details, the woman said that Marcky might be better off in a home without any other children around. She said it could work out all right, though, that often there were no problems at all.

But that wall of doubts the caseworker had erected around Marcky was enough. If it had been just the three of us — Haiden, Marcky, and me — I think we could have made it work. But it wasn’t going to be just us three.

We told DeMarckus’s caseworker we would keep the boy for now, until she found another suitable foster home, but that, after thinking it through, we weren’t going to adopt him.

For Hydrangea, Marcky picked out two realistic-looking brown mice filled with catnip and handed them to me along with his five-dollar bill. “You pay,” he said.

While the store owner rang up the mice, Marcky stood by my side and drummed his fingers on the counter. “Excuse me, lady,” he said. I thought maybe he wanted to tell her about Hydrangea or let her know he was paying for these gifts with his own money. But Marcky looked concerned, his eyebrows close together.

“Yes, young man?” the store owner asked.

“Those cats back there,” Marcky said. He pointed toward the back of the store. “Where do they live when it isn’t Saturday?”

The woman smiled and said, “Well, their real house is the animal shelter.”

“Then what?” Marcky said.

The store owner turned to me, and I shrugged, as if to say, Are six-year-olds supposed to know about the inner workings of animal shelters?

“Well —”

Marcky stopped her. “I don’t want the mice,” he said. “I want to give all my money to the kitties.”

“Oh, honey,” the woman said. “I don’t think —”

“To the kitties,” he said. “All five dollars.”

I reached to put my arm around Marcky, but he pulled his shoulder away from my hand. I had never seen the boy so serious looking. “All I want is to give the money to the cats,” he said. “Maybe especially Roosevelt.”

On previous trips to the store, I had entertained the idea that Marcky had an intuition about the animals’ plight, but the boy’s interest in the cats had always seemed uncomplicated, as if he liked them more for their catness than anything else, the way any kid would. But this — this felt different.

“All right,” I told him. “It’s your money.”

The store owner asked us to wait, and she snagged the college girl, who brought out a marker and a donation sheet shaped like a cat’s paw. Marcky placed the paw on the store’s counter, and I spelled out his name for him, one letter at a time. Meanwhile the store owner produced a Polaroid camera to take our picture.

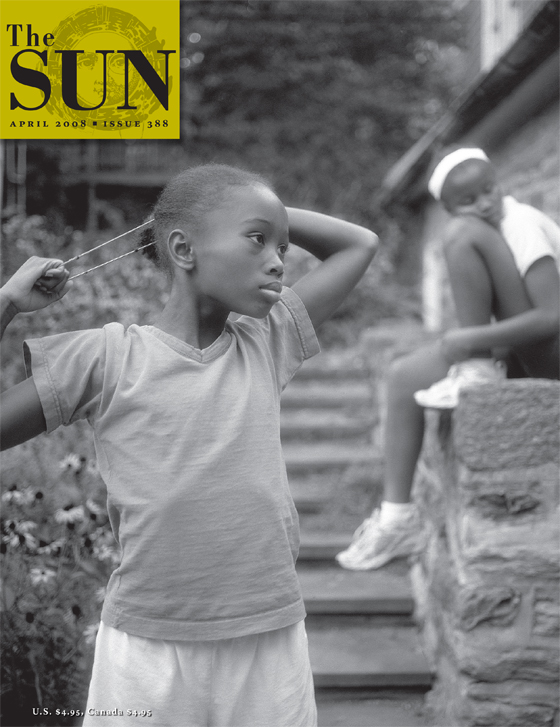

In the photos Haiden and I have of Marcky, he is only half smiling, as if he has just asked a question and received an answer he doesn’t understand. When I look at those pictures now, I smell the boy’s bad morning breath; I see the streaks of toothpaste he used to leave in the sink.

The college girl stood behind Marcky, bent at the waist, and placed both her hands on his shoulders. I tried to slink out of the shot while the store owner looked through the camera’s viewfinder.

“Oh, no,” she said. “Get back there, you.”

I stood behind them and off to the side, just barely caught by the camera’s flash. The store owner took two pictures: one to attach to the cat’s paw Marcky had signed, and one for us to have as a keepsake.

On the drive home from the pet store, Marcky fiddled with the window button and asked his typical six-year-old questions, like “Do flowers have feelings?” or “Superman isn’t really a man, right?” His mind had already moved on to something else. I tried to answer his questions as best I could, but my head was filled with All I want is to give the money to the cats. Maybe especially Roosevelt.

When we made it home, Haiden was in the kitchen making a salad, and all signs of sickness had left her face. Marcky bounded through the kitchen on his way to the television. The Polaroid, I would find out later, was still in the car, where Marcky had dropped it.

“How was your trip to the pet store?” Haiden asked as she halved a couple of grape tomatoes and tossed them into a bowl.

“Well,” I said, “it looks like we have a hero down at Hardware & Pets.”

Haiden, of course, had no way of knowing what I meant, but she placed her knife on the counter, smiled, and said, “Come here.”

And I held her there in the kitchen, with the bump of Ben between us. We were so isolated, yet so together right then. We held one another and didn’t let go, and it felt as if we were waiting: For Marcky to gag over the coffee table. For him to say, “Applesauce.” For anything from him at all.