When I first met Sy Safransky in person nearly twenty years ago, I was surprised. From reading his writing, with his frequent references to overeating, I was expecting someone paunchy and out of shape, like me. So I was startled when a tall, trim, bespectacled guy in jeans stood up to greet me. The most remarkable thing about him were his clear, kind eyes — that, and the preternatural tidiness of his desk. Around his office were images of various holy men — Buddha, Jesus, the Dalai Lama, and someone I didn’t recognize. (Safransky told me it was a Hindu guru named Neem Karoli Baba.) In the corner was a broken Underwood manual typewriter — the god at whose altar he’d worshipped for many years, Safransky said.

Full disclosure: I work part time for and contribute to The Sun. I first discovered it in 1992 at a friend’s home in Hawaii. I sat on her porch one bright morning with a view of the valley, a pot of coffee, and a stack of Suns. I really liked the first piece I read. And the next was extraordinary. Then I read Readers Write and some poems.

I spent that summer on a ship, writing by hand a short story that I hoped to submit to the magazine. In the fall I sent in the story with a check for “as many issues as ten dollars will buy me.” Both were accepted. Since then I’ve read every word of every issue, starting at the front and working my way to the back, making me, Safransky says, his “dream reader.”

Getting Safransky to grant this interview took two years of polite, persistent persuasion. As The Sun’s fortieth anniversary approached, he finally conceded that his answers to a few questions about the magazine might be of interest to some readers. Even then, he insisted that I remain as objective as possible in the introduction.

The eldest of two children, Safransky was born in 1945 and grew up in Brooklyn, New York — “before Brooklyn was hip,” he says. He was the son of working-class Democrats who imparted to him a strong sense of social justice. Safransky’s father, who had once aspired to be a writer, excelled at editing his son’s writing. For a living he worked as a salesman, sometimes selling encyclopedias as well as a set of classics called Great Books of the Western World.

Safransky edited both his junior-high and high-school newspapers. At Queens College, part of the City University of New York, he was a political-science major, but after he became editor of the campus newspaper, The Phoenix, he spent more time in its offices than he did in class. In 1966 he got a master’s in journalism from Columbia University and went to work for The Long Island Press, then the seventh-largest afternoon daily in the country. As a reporter, Safransky covered everything from the police beat to social and political issues. He left after three years because he was dissatisfied with the job and with the state of journalism in general.

He and his first wife spent a year traveling through Europe and living in a van, “discovering what the sixties were about just as the sixties were ending,” Safransky says. They lived in London for another year, then came back to the U.S. and moved to Chapel Hill, North Carolina, to join an intentional community. Rather than return to daily journalism, Safransky worked odd jobs. In 1973 he was running a one-man juice bar. A kindred spirit named Mike Mathers owned an independent bookstore across the street, and sometimes he would call in his juice order, and Safransky would deliver it and stay to talk. One day they realized that they both fantasized about starting a publication. They lacked the $1 million that conventional wisdom said was needed to start a magazine back then. In fact, they had no money at all, nor a business plan. They didn’t even know any professional writers. But they did have enough imagination and will to come up with most of the first issue themselves. Called The Chapel Hill Sun, it was crudely photocopied, and the content was, at best, uneven. Mathers left the magazine a few years later, but Safransky had faith that if he stuck with it, he would attract better writers and more readers. And it turned out he was right, though it took longer than he thought. [For more on the magazine’s history, see “Beginnings, Blunders, and Eleventh-Hour Rescues.” —Ed.]

Over the years I’ve known him, I’ve come to think of Sy (enough of this “Safransky” business; objectivity be damned) as a friend. On a cool, mosquito-thick fall evening in 2011, we sat at his house and talked and argued and agreed about love and sex and Yeats and God. During that terrific conversation, I made messy, incoherent notes in the margins of some printed Google Maps directions. Earlier I’d read to Sy parts of an essay I’d started writing, sloppily, on many mismatched sheets of paper. We laughed at my scribbles, then laughed again when Sy showed me a couple of the small, finely ruled loose-leaf binders in which he keeps his journal, the source of his published Notebooks. Each entry was neatly written in black ink. Sy told me that when he makes a mistake, he corrects it with Wite-Out.

This interview was conducted by telephone in the summer and fall of 2013. I’m grateful to Sy not only for granting it but for his technical know-how: On the first day of taping, he asked, “Did you press play and record? A lot of good interviews have gone into the great beyond.” This one didn’t. Here is Sy Safransky on the publication he’s made his life’s work.

Kendall: When asked how The Sun began, you usually talk about your experiences as a New York City journalist. But more recently, at a Sun writing retreat, you talked about an LSD trip that changed your way of thinking.

Safransky: I said that I never would have started The Sun were it not for LSD. I don’t usually talk about that, because I think some readers might be dismayed to hear it. But I also believe it’s important to honor our teachers, regardless of the form they take, and for me LSD was an extraordinary teacher. It was a key to a door I didn’t even know existed — and once I opened that door, in my midtwenties, I was irrevocably changed. I’ve often referred to being The Sun’s editor and publisher as “my spiritual path disguised as a desk job.” But the very notion of being on a “spiritual path” was foreign to me before I did LSD. As Ram Dass, another of my teachers, said, “I didn’t have one whiff of God until I took psychedelics.”

I’d been raised Jewish but wasn’t observant. I prided myself on being a hardheaded realist who scoffed at religion and didn’t do drugs. But in 1969, when I was traveling in Europe, I met a German hippie who handed me some LSD. He promised that it would “make everything beautiful.” I carried it around for months, unsure whether to try it or throw it away.

When I finally took it, what happened was beyond “beautiful.” The boundaries between myself and the world began to dissolve. And I realized, not just in my head but in every cell of my body, that the plants and the trees and the clouds and the birds weren’t separate from me or from each other. Somehow we were connected. And instead of being frightened by this, I felt a great sense of relief, as if I’d finally stumbled upon a truth that had eluded me all my life. I knew I was on LSD, but I also knew I was seeing something clearly for the first time.

I also remember sitting with my eyes closed, transfixed by an endless stream of vivid and intricate images. I intuitively understood these complex symbols as if they were some kind of code — about myself, about my past, about the nature of reality. Then, after what seemed like hours, I opened my eyes, glanced at my watch, and stared in disbelief: only five minutes had gone by. I took off the watch that afternoon and left it off. It wasn’t until I started The Sun several years later that I put it back on. I had deadlines to meet, after all.

But what I remember most about that day was that my heart opened in a way it never had before. I felt a powerful and all-encompassing love, not for anyone or anything in particular but for all of creation. And the next time I did LSD, a few months later, I felt that unconditional love again. I felt it every time I did LSD. I also saw more clearly that behind our seemingly separate bodies and personalities we share one consciousness. And, over time, I realized that if I was willing to leave a little more of “Sy” at the door, if you will, I’d experience myself as part of something far more interesting: everything that wasn’t me. Then, on one trip, I no longer had a choice about how much of “Sy” to leave behind. I was “gone, gone beyond, gone beyond beyond,” as the Buddhists say. And when I finally came back from that place where “I” no longer seemed to exist, when I was back in my body and back in my more-or-less-rightful mind, the love coursing through me was exponentially more powerful and more expansive than ever before. And I knew with absolute certainty that all I wanted to do from then on was to serve others. And I knew, too, that the best way to do this was never to announce it; that if you wear your spiritual heart on your sleeve, even though it might come from good intentions, it will inevitably create a sense of separation between yourself and another person.

By the time I put out the first issue of The Sun in January 1974, my zeal for mysticism and altered states of consciousness had been tempered by the realization that meditating in the morning and yakking about God late into the night provided no immunity from life’s bruising surprises.

Kendall: Why have you been hesitant to discuss this?

Safransky: I’ve been hesitant because there’s a lot of misinformation about LSD in this culture. Unfortunately, many people have a tendency to lump all illegal drugs together, making no distinction between addictive substances like heroin or cocaine or methamphetamines, for example, and hallucinogens like LSD. In any event, for me LSD wasn’t a recreational drug. Usually I was alone when I did it, and I approached it as a kind of religious sacrament. I do feel obliged to mention that not every trip was a positive experience. I found my way into some hell realms, too, that I’d never want to revisit. And, though I think LSD’s dangers have been exaggerated, I don’t advocate anyone taking it. I’m also not suggesting that tripping is a prerequisite for getting a taste of a transcendent reality. There are other, probably better, ways to get there. But before I did LSD, I didn’t even know there was a there to get to. So I’m grateful for that glimpse.

Having said all that, it’s possible that I’m totally wrong about this, and that LSD really screwed me up. Maybe it turned a serious and levelheaded young journalist into a muddle-headed fool willing to take wild risks, like starting a magazine with no idea what the hell he was doing.

Kendall: When did you stop taking LSD, and why?

Safransky: I haven’t done LSD in many years. I don’t miss it. Neither do I regret having done it. Eventually I realized that LSD was like a helicopter that dropped you at the top of a mountain, so you could take in the view without having made the climb. But the helicopter was on a tight schedule; it picked you up twelve hours later to bring you back down. If I wanted to keep experiencing that connection to everything and everyone, I could either do LSD all the time, which didn’t seem like an ideal strategy, or devote myself to some kind of spiritual practice — in other words, climb the mountain one step at a time. So I started meditating. I took up yoga. I began reading books with hard-to-pronounce names like the Tao Te Ching and the Bhagavad-Gita.

Then something else happened that had a lot to do with how the magazine would evolve. In the summer of 1972 my son, Joshua, was born prematurely and lived only three days.

It was the most painful, disorienting loss of my life. For a long time afterward I saw no reason to get out of bed, or talk to anyone, or do anything. I was as incapable of comforting my grieving wife as I was of finding any comfort in those holy books on the shelf. It was the first test of my nascent spirituality — and anything I’d learned while tripping, anything I’d underlined in my anthologies of Eastern wisdom, made about as much sense to me as a loose shutter banging in the wind.

A few months after Joshua died, my wife, Judy, and I split up, the intentional community we’d moved to North Carolina to join fell apart, and my father was diagnosed with terminal cancer. By the time I put out the first issue of The Sun in January 1974, my zeal for mysticism and altered states of consciousness had been tempered by the realization that meditating in the morning and yakking about God late into the night provided no immunity from life’s bruising surprises. But I must say that grieving these losses did deepen my compassion for others. I think that a tried-and-true way to become more compassionate is to suffer plenty yourself. It may leave you embittered and cynical for a while, but, ideally, it will open your heart, and once your heart is open, it’s easier to empathize with someone else’s brokenness.

I decided early on that The Sun would never ignore how unbelievably challenging life can be. Each time I slipped up in those first few years by publishing pie-in-the-sky theology and loose talk about enlightenment, I increased my efforts to make The Sun more down-to-earth and less self-consciously spiritual.

Besides, I’ve never wanted The Sun to be easy to pigeonhole. When people first pick it up, I want them to be unsure what it is. I don’t want them to be able to slap a label on it, especially the label “spiritual.” Labels are OK on spice jars, but not on The Sun.

Kendall: Even after having read it for twenty years, some of us don’t know what The Sun is.

Safransky: That’s OK. We don’t know what anything is, really. Everything is mysterious, so why not a magazine that honors the mystery?

Kendall: How did you support yourself in the early days?

Safransky: When I started The Sun, I could pay myself only a subsistence wage, and that was fine with me. Doing work I loved was more important to me than being well paid and living in a comfortable house or driving a new car. In fact, I thought there was something noble about choosing to be poor, that it conferred a kind of grace unavailable to the rich. So while I was committed to The Sun’s survival, I was definitely not interested in it becoming a “success,” because I equated success with compromise, with selling out.

As the readership has grown and the magazine has become more financially secure, it doesn’t seem as if anything important has been compromised. We stopped carrying advertising in 1990, which is about as far from selling out as you can get. We’re still committed to ethical business practices, and to relating to our readers as individuals, not as a demographic. And it turns out I don’t have to compromise the magazine in order for everyone who works here to earn a decent salary, and for our writers and photographers to be fairly compensated, and for the bills to be paid each month, with a little left over for a rainy day. I’ve got to agree with the novelist Tom Robbins, who wrote that there’s a certain Buddha-like calm that comes from having some money in the bank.

But I try not to let the magazine’s success and my own good fortune distract me from the enormous injustices in the world. I still think the primary responsibility each of us has is to try to reduce suffering as much as possible and not create more of it. Whatever inroads The Sun can make in that regard would, to my mind, be the greatest measure of the magazine’s success.

Kendall: Apart from your vision, the hardworking staff, the devoted and engaged readers, the arts grants, and the good luck, do you think The Sun might have a spiritual or metaphysical source of assistance?

Safransky: Well, I don’t have God’s unlisted number. But I agree with you that something else might be going on here. Then again, aren’t we all sustained by unseen forces we can’t really understand? In this instance, I suppose I’d call it some kind of grace, though I don’t presume to understand it.

Kendall: You often refer to God in your Notebook, but you rarely disclose definite beliefs. What do you think of God?

Safransky: First, I want to know what God thinks of me! [Laughter.] On second thought, strike that. [Long pause, sigh.] Look, it’s hard for me to talk about God, and not because I’m trying to be evasive. It’s because there’s an obvious dilemma in trying to express the inexpressible. When I was a kid, I was taught in Hebrew school that it was a sin to speak or write the Hebrew name for “God,” that it would make God angry if we used his “real” name. In recent years, it occurred to me what might be behind this injunction: since whatever we mean by “God” is, in fact, nameless and unknowable, it’s good to remind ourselves, every time we use the word, that there really isn’t a word for what we’re trying to express. Groucho Marx said he wouldn’t want to belong to any club that would accept him as a member. Well, I wouldn’t want to believe in any God that I could comprehend.

Kendall: Marxist scholar Terry Eagleton often speaks in defense of God, arguing with atheist philosopher Richard Dawkins that God is not the God that atheists do not believe in. I once asked Terry, who was my tutor, to say what he thought God was, and he gave me an answer similar to yours. He said this problem goes back to the ancient Greeks or thereabouts — the inability to make concrete assertions about the nature of God.

Safransky: I think about what Saint Augustine said: “I know what God is as long as you don’t ask me.” To which I’d add: “and as long as I don’t ask myself.” Because when I struggle to articulate what I know in my heart, I trip over my own words. It’s easier for me to make jokes in my Notebook about an Old Testament God with a terrible temper and a narcissistic personality disorder than it is for me to talk about God in a humble and clear way. Actually my ideas about God don’t interest me much. They’re just the result of the mind doing what the mind does when it can’t understand what’s beyond the mind.

In my more lucid moments I know that God is right here, right now; that God is the luminous mystery at the heart of creation and that God is here in the joys and sorrows of the world. And I try to see God in everything and treat all life with reverence. But in this not-very-lucid moment, I’ll fall back on what I call my “shower epiphany.” It happened a few years ago — in the shower, of course. Maybe it was all those negative ions. Maybe it was the soap. In any event, I suddenly realized that anything I can say about truth — anything — is bound to be wrong. But that doesn’t make the truth any less true. I found this strangely comforting then, as I do now. Truth doesn’t depend on me to define it. God doesn’t depend on me to know what God is.

Kendall: Sparrow, a writer whose work you publish regularly, said to me a few years ago that, based on a conversation with you, he thought you were less depressed than you used to be, and as a consequence the magazine was less depressing. Do you have any thoughts about that?

Safransky: I can only speculate: maybe Sparrow and I had that conversation when I was on an antidepressant, which was supposed to make me less depressed.

Kendall: Or at least antidepressed.

Safransky: Antidepressed! What a great slogan that would be for a movement. Instead of marching against war, we’d march against depression, that terrible war within ourselves.

I’ve tried a few antidepressants over the years. After all, I’m liberal-minded: I don’t limit myself to illegal drugs. And I’ve found value in legally prescribed pharmaceuticals — although, just as with illegal drugs, they often leave something to be desired.

Even without those pills — which I don’t take anymore — I probably am less melancholic than I used to be. Some of it has to do with getting older, I think. Maybe I’ve learned something from having been knocked on my ass again and again. Getting back up doesn’t take as long as it once did, even if I’m the one who’s thrown the punch. Also I’ve spent years in therapy with a psychologist named Victor Zinn, whose wisdom has brought me back to my senses innumerable times. And I’m fortunate enough to be married to a skillful and compassionate therapist. Norma’s not my therapist, of course. But she is my loving wife. Sometimes the gods shower a man with blessings he doesn’t deserve.

Kendall: The Sun has its detractors. I know some people who’ve become disillusioned with the magazine or turned away from it, and I’ve tried to bring them back by telling them it’s more upbeat than it used to be. What’s your response to people who complain that the magazine is too dark?

Safransky: I wouldn’t try to talk someone into feeling differently about The Sun. That would be like insisting a lover always find you incredibly sexy, even after the bloom is off the rose. Look, I know that The Sun can be a difficult magazine to read, not because it’s intellectually intimidating but because our writers are honest, often painfully honest. Not everyone is ready at all times to confront the hard truths about the human condition. Maybe someone is having a tough year and doesn’t need that reminder. Her heart’s just been broken. It doesn’t need to be broken again.

There are other reasons some readers call it quits. Maybe they love the personal writing but not the more overtly political interviews on poverty or racism or other social ills. And some readers seem to think that if the editor has unkind thoughts about callous and mendacious politicians, he should keep them to himself.

It’s important to me to bring what’s beautiful and inspiring to readers, but not to the exclusion of what’s not so beautiful and not so inspiring. It’s important to remind our readers of the suffering all around us. Here we are in the midst of wars that never seem to end, environmental disasters, the perpetuation of glaring social and economic injustices. I want The Sun to embrace all aspects of the human experience.

Of course what we leave out of the magazine is just as critical as what we include. Sometimes I joke that it’s a full-time job deciding what doesn’t go into The Sun.

Kendall: What sort of writing doesn’t go into The Sun?

Safransky: What I don’t want in The Sun is slick, overly clever writing. I don’t want facile social commentary written by people presuming to speak for others. I don’t want left-wing sanctimoniousness or right-wing duplicity. I don’t want the kind of positive thinking that gives thinking a bad name.

In the course of a year we publish nearly a half million words, and I want to make sure they’re the right words, not the almost-right words. I want to make sure they’re words that bring us together, because I want The Sun to remind us that separateness is an illusion — a very compelling illusion, but an illusion nonetheless. Are we really separate from this earth? Are we really separate from one another? This separate self we cling to — how real is it?

Kendall: You mentioned meditation earlier. Do you still make time for it?

Safransky: Not as regularly as I’d like. But recently I’ve tried to be more consistent, and to get inspired I’ve been reading a few pages every morning of Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, by Shunryu Suzuki (or Suzuki Roshi, as he’s commonly called), one of the first Zen teachers to come to the United States from Japan. I’ve also just read an essay about him by the American Buddhist teacher Norman Fischer, who says that Suzuki Roshi often talked of how “stupid” he was: When Suzuki Roshi was still a boy at his teacher’s temple, all the other students ran away because the teacher was so tough. Suzuki Roshi was the only one who didn’t run away — not because he was particularly adept but because he didn’t realize that he could run away. I love that. Maybe I’ve also been too stupid to quit, especially when I had no earthly idea how to keep The Sun alive from month to month.

Let me read you a few lines from Fischer’s essay: “He just went on with the practice every day no matter what happened, for his whole life. And in his teaching he emphasized that kind of steadiness and faithfulness. . . . He emphasized routine and repetition. He taught that just by doing the practice, over and over again, without expectation of any result, but being as present as possible with it, something subtle would happen. Unlike other teachers of his time and now, he did not travel all over giving talks. He just stayed around the temple taking care of things — and, you know, taking care of his practice.”

I found that particularly inspiring, though maybe not in the way Fischer intended. I tend to judge myself harshly for not having a more regular spiritual practice. Referring to my work on The Sun as my “spiritual path” can seem glib to me. To really be on a spiritual path, I should be meditating every day. But I don’t meditate every day. I should be praying every day. But I don’t pray every day. There is something I am consistent about, though, something I do nearly every morning, as well as most of the day and into the night: I attend to The Sun. I take care of things around the temple. That’s never seemed like enough — and maybe it isn’t — but it’s a practice to which I’ve been undeniably faithful for nearly forty years. So maybe I can accept that The Sun is my meditation; that The Sun is my prayer. And maybe that’s as good as it’s going to get. And maybe that’s enough.

On the other hand, it’s useful for me to recall what Suzuki Roshi said to his students: “All of you are perfect just as you are, and you could use a little improvement.”

Kendall: What is the hardest part of your work?

Safransky: The hardest part? That’s easy: the work. I had no idea how demanding the task of editing and publishing The Sun would become. I don’t work as hard as I did in the early days, but fifty- and sixty-hour weeks are still the norm for me. This isn’t a complaint. It’s just a fact. What’s funny is that I still pretend that if I just work harder, I’ll get caught up. This is utterly delusional, of course. It’s like a general insisting that sending another ten thousand troops to Vietnam or Iraq or Afghanistan will turn the tide of the war.

It’s still a struggle for me to decide what to publish, to find the right balance for each issue. It’s still a struggle for me to find time to write. It’s still a struggle for me to manage a staff. Many times a day I come up against my limitations as an editor, as a publisher, as a writer, as a flawed human being. It’s humbling, as it should be.

For example, I’m humbled by the fact that, before I started The Sun, I responded to letters promptly. Of course, I didn’t get many letters back then. One of my biggest regrets is that I’ve turned into someone who doesn’t keep up with his correspondence — and that includes responses to heartfelt, thoughtful letters from old friends or from writers we’ve published or from longtime readers who shouldn’t have to wait months or even years for a reply. Yes, years. The journalist H.L. Mencken said that if he writes to someone and fails to get a prompt reply, “I set him down as a boor and an ass.” I couldn’t agree more.

Also it’s never been easy to say no to writers who submit their work for publication. We receive nearly a thousand submissions a month, and we send back 99 percent of them. We do our best to be kind, but there’s not much I can do to take the sting out of it. They’re not called rejection letters for nothing.

Unfortunately, as I’ve gotten older, I’ve become even harder to please. I worry that maybe I’ll get to where I don’t like anything. I’ve struggled with this, but if I were satisfied with the same kind of submissions I accepted thirty or forty years ago, it would mean that neither I nor the magazine had grown. Still, I’m afraid I’ll become like my mother: no matter where we went out to eat, and no matter what she ordered, she’d find a reason to send the food back.

Kendall: When I first met you nearly twenty years ago, you said that you tried to be mindful about your daily work, paying attention to only one thing at a time.

Safransky: One thing at a time? That’s what I said? I wish. That’s the ideal, but it’s quite a challenge, isn’t it? Actually, working long hours is the easy part. What’s more difficult is not to get lost in or overwhelmed by the stacks of manuscripts and memos and spreadsheets. You know, there’s a story about God and the devil walking down the street. God bends down and picks something up. It glows in his hand. The devil asks what it is. God says, “This is truth.” The devil says, “Let me have that. I’ll organize it for you.”

This is what happens in all “organized” religions and in every nonprofit that’s trying to do some good in the world. It’s not because we’re evil. It’s because we’re human. I can get so absorbed in the endless details of organizing the truth that I forget why I’m here. I used to have a poem by Theodor Storm over my desk. It’s titled, appropriately enough, “At the Desk,” and it goes like this: “I spent the entire day in official details / And it almost pulled me down like the others: / I felt that tiny insane voluptuousness, / Getting this done, finally finishing that.” I suspect that this experience is shared by many.

It’s still a struggle for me to decide what to publish, to find the right balance for each issue. It’s still a struggle for me to find time to write. It’s still a struggle for me to manage a staff. Many times a day I come up against my limitations as an editor, as a publisher, as a writer, as a flawed human being. It’s humbling, as it should be.

Kendall: In all the time you’ve been creating The Sun, how has the work changed you?

Safransky: It’s hard to say how something has changed you, because you don’t know how your life might have been different otherwise. It’s not a scientific experiment; there’s no control you. In any event, I’m not sure I’ve changed all that much. I’m still gaining and losing the same twenty pounds. I still habitually focus on what I haven’t gotten done instead of what I’ve accomplished. I still type with two fingers. I still question whether I’m a real writer. Maybe I’ve become a more skillful editor, but I’ll never be as adept as I’d like to be. My politics haven’t changed. Maybe I’ve gotten a little wiser, but to myself I still sound like just another Jewish wiseguy. And of course, notwithstanding all the LSD and the meditation and the religious tomes, I still struggle to stay awake. It’s the human condition, I suppose. We fall asleep, and we wake up, and then we fall asleep again.

I am heartened by one change: The Sun’s very existence attests to the value of perseverance and to the wisdom of sometimes ignoring conventional wisdom. So I can now say to someone unsure of his or her next step in life: You, too, can do something that doesn’t make sense to your guidance counselor or your parents or your friends or your spouse or your children or your grandchildren or the nurse’s aide in the assisted-care facility who pats you on the shoulder and tells you to “settle down, dear.” After forty years, with whatever authority comes from lived experience, I can say: You, too, can create something. You can nurture it and watch it grow. A progressive social movement? Go ahead. Another independent magazine? Be my guest. After all, we weren’t put here to make all the same mistakes made by the generations that came before us. We’ll repeat many of them, for sure. But there’s no telling what can happen if we’re steadfast and true and faithful to our practice.

The Sun has always been bigger than me. Wiser than me. Steadier than me. One of the satisfactions of publishing it for all these years is that I’ve gotten to see what happens when like-minded people work together toward a common goal.

Kendall: A friend of yours, Unitarian Universalist minister Doug Wilson, has said that the surest way to get published in The Sun is to write an angry letter denouncing the editor. You do print a lot of negative letters. Are they disproportionate to the number you receive? And why do you publish so much harsh criticism of yourself, the Notebook, and the magazine?

Safransky: Yes, the number of negative letters we print is disproportionate to the number we receive. But I believe it’s only fair to let our detractors have their say. Besides, I’m probably my own worst critic, so it’s a relief when others share that burden.

Kendall: What’s been your biggest mistake as an editor?

Safransky: We’ve made some egregious editorial mistakes. I’ve made a few bad hiring decisions, then dithered around, hoping it would magically work out — an even bigger mistake. Of course my worst mistakes are probably those I don’t know I’ve made. And I’m sure there are writers who’d say, “Hey, man, the biggest mistake you made was rejecting my work.”

Kendall: Are you competitive?

Safransky: Mostly I’m competitive with myself, or with an idealized version of myself — someone who writes like me, only better; who puts out a magazine like The Sun, only better.

Kendall: Has working as an editor improved your writing?

Safransky: I doubt it. The only way to improve your writing is to sit down and write.

Kendall: Tell me about your notebooks. What do they look like?

Safransky: They’re black loose-leaf binders seven and a half inches high by five inches wide. Something about this proportion feels right to me. The paper is narrow ruled, thirty lines to a page. This encourages small handwriting, which I originally hoped would keep my ego in check — obviously a failed experiment. Unfortunately no one manufactures these binders anymore, so I have them custom made.

Kendall: No!

Safransky: I’m not kidding. The paper, too.

Kendall: The paper? Do they grow the trees for you?

Safransky: [Laughter.] Cut me some slack, Gillian. Lots of writers are particular this way. Kerouac wrote On The Road on one continuous scroll of paper. Nabokov wrote most of his novels on three-by-five index cards. Dumas wrote his fiction on a certain shade of blue paper. Once, when he was traveling, he had to use a cream-colored pad. He was convinced his work suffered.

Kendall: How many of these notebooks do you have lined up for the future? You must order them by the case.

Safransky: At my age, if I order too many it can seem presumptuous.

Kendall: Any closing thoughts on The Sun’s fortieth anniversary?

Safransky: Norma and I just celebrated our thirtieth wedding anniversary, so I feel confident in saying that keeping a magazine alive is like keeping a marriage alive: it takes a lot of love and a lot of hard work. But I’d never pretend to be an expert about anything as confounding as publishing, or marriage. Maybe I’ve merely been the beneficiary of an exceptionally long lucky streak, or maybe it’s something in the drinking water or in the alignment of the stars. Better not to jinx it. I know that other dedicated editors work just as hard, and other couples seem just as loving, yet their magazines and marriages come crashing. Still, that doesn’t mean they’ve failed. As Hermann Hesse wrote, “Some of us think holding on makes us strong, but sometimes it is letting go.”

I also want to say that, while it’s tempting to conflate The Sun and Sy Safransky, I’m only part of the story. It’s true that I founded the magazine and sold it on the street and worked my ass off. I still work my ass off. But many other people here work hard, too, and always have. From the very beginning The Sun has been a collective endeavor, shaped and strengthened by every person who has worked beside me or written for the magazine or paid for a subscription or bailed us out when we were close to bankruptcy. The Sun has always been bigger than me. Wiser than me. Steadier than me. One of the satisfactions of publishing it for all these years is that I’ve gotten to see what happens when like-minded people work together toward a common goal.

Kendall: You’ve said you want to go on editing The Sun “forever.”

Safransky: Of course I do. The rhythm of putting together a magazine every month suits me, just as breathing in and breathing out suits me. But if there’s a first day, there’s a last day. I know I’m only renting here. Until the eviction notice arrives, though, there’s nothing I’d rather do than keep devoting myself to this work. In the realm of publishing — hell, in any realm — The Sun’s very existence is a miracle. I’m still amazed that we meet our deadlines and get an issue into our readers’ hands once a month, and that they sit down and read it. I don’t need to see the holy dove flapping its wings outside my window to know I’m blessed.

Kendall: When you look back on it now, do you think you had any idea what you were getting into when you started the magazine?

Safransky: No. I didn’t have a clue. It’s like becoming a parent. If people knew ahead of time just how challenging raising a child was going to be — I mean, if they really knew — they might say, “That’s not for me.” But of course once you have a child, everything changes.

Kendall: You hope.

Safransky: Well, it did for me. Because you fall in love with that child, the way I did with my two daughters, and no matter how difficult life gets, it’s worth it, because you can’t imagine a life without those children. And what you do for them doesn’t feel like a sacrifice.

Once I started The Sun, everything changed. It doesn’t really matter that often I’m too busy to get a decent night’s sleep, or take a real vacation, or curl up with a good book instead of a stack of manuscripts. Maybe in my next lifetime I’ll sleep until noon and sail the seven seas and read all the classics. Maybe I’ll hit a home run in Yankee Stadium in the bottom of the ninth while tripping on the purest, most mind-blowing LSD in God’s creation. Then I’ll lope around the bases, entranced by the tangerine trees and marmalade skies. And it won’t matter how much time has passed since I sent that ball soaring. Maybe it was five minutes. Maybe it was forty years.

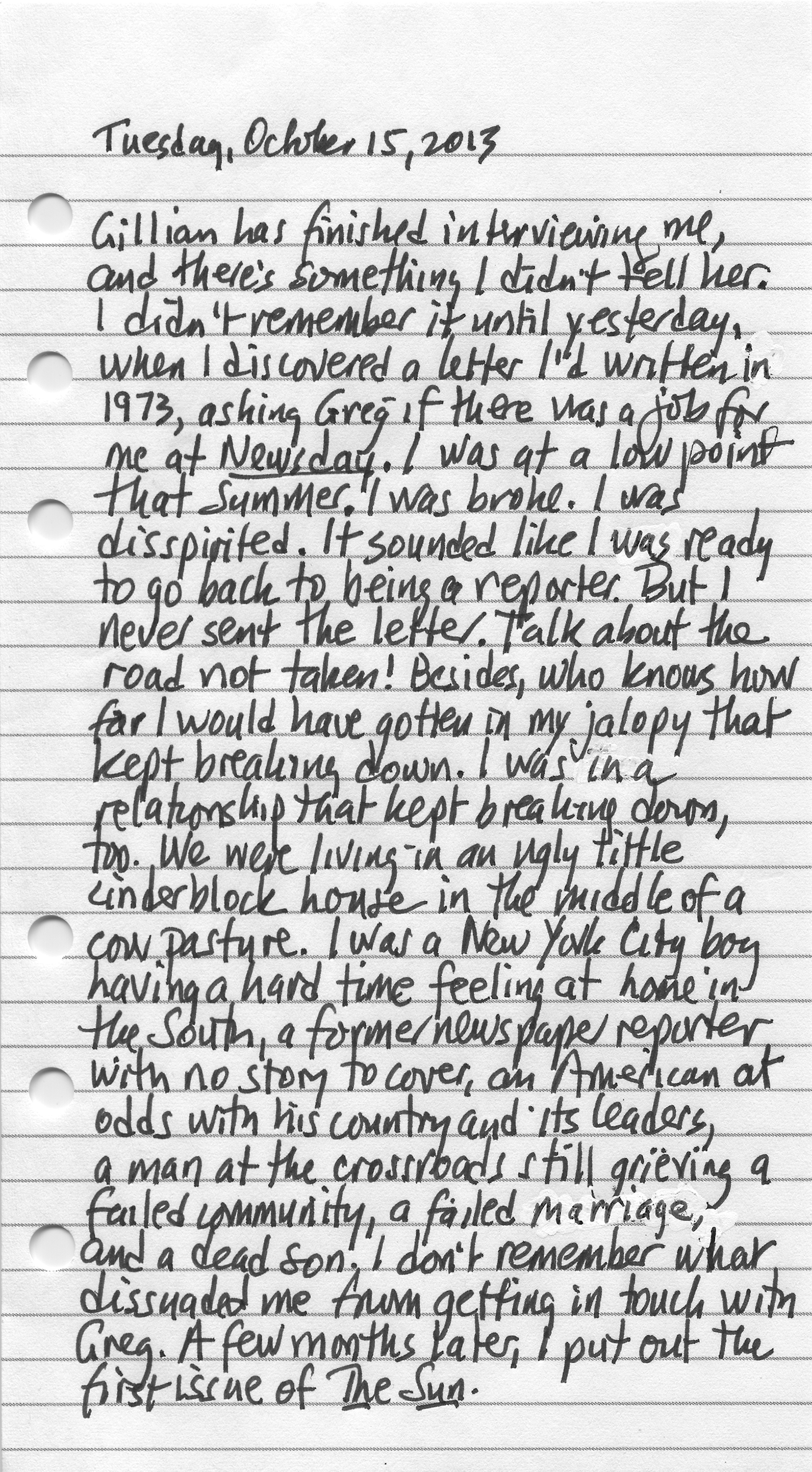

An entry from Sy Safransky’s journal — with “dispirited” misspelled.