They are a select group of corporate officers who travel the Third World and hobnob with heads of state. Their job is to convince the governments of poor nations to build expensive new power plants, shipping ports, and industrial parks using borrowed funds. They call themselves “economic hit men,” and they destroy their targets not with bullets, but with dollars.

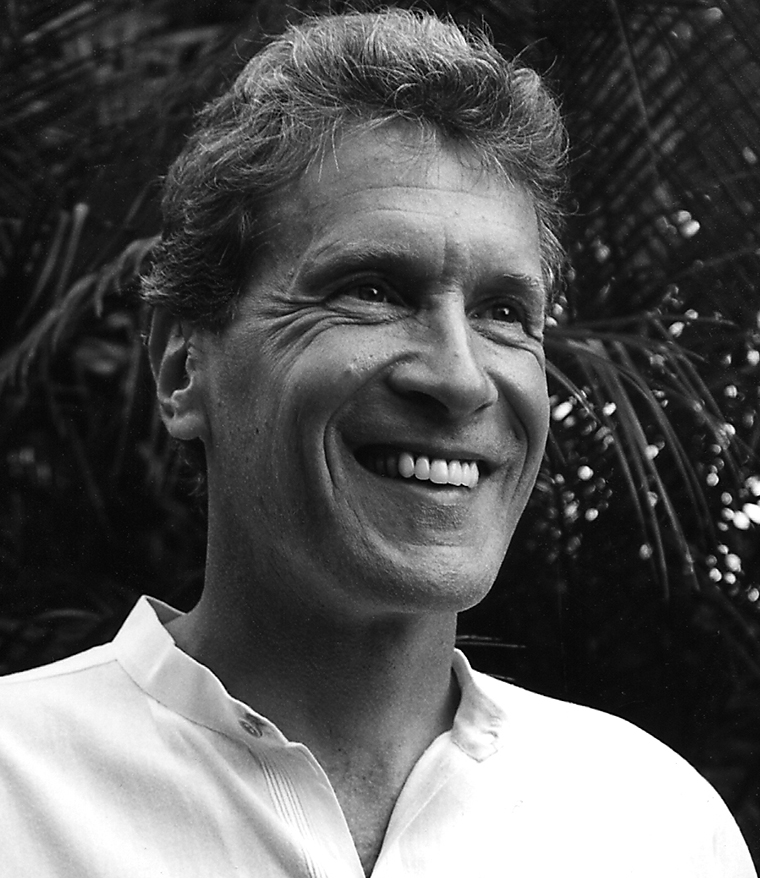

John Perkins was once one of them. In his book Confessions of an Economic Hit Man (Berrett-Koehler) he tells how the system worked — and still works today: He and his fellow economic hit men befriended Third World leaders and convinced them, often using bribery or deceit, to take on enormous debts to develop their national infrastructure. U.S. corporations profited from the development contracts, and the World Bank — source of the majority of the loans — profited from the interest. The only ones who didn’t profit were the Third World nations themselves, who found they were unable to pay back the money they owed.

Perkins graduated from Boston University in 1968 and spent the next three years in the Peace Corps. Then, from 1971 to 1980, he served as chief economist at the engineering and consulting firm of Chas. T. Main (or MAIN), a low-profile international corporation based in Boston. As part of his duties, Perkins says, he inflated the economic projections of development projects being sold to Third World countries so that the country in question would be induced to take out exorbitant loans to pay for the project — which, of course, could be built only by a U.S. corporation.

According to Perkins, this was more than a plot to make money for his employer and the banks. The countries were selected by the U.S. government for their strategic value or resources. Once crippled by debt, each country was beholden to the international banking community and unable to refuse if the U.S. wanted to build a military base or drill for oil within its borders.

But that’s not all. Perkins claims that the economic “hit” was only the first line of attack. If it failed, then CIA “jackals” were sent in to stage a coup or assassinate an uncooperative leader. If that, too, failed, then the U.S. would resort to military action. In his book Perkins reveals this information in a decidedly evenhanded manner, taking responsibility for his own complicity and acknowledging the lure of money and power for those who are willing to play the game.

In 1980 Perkins resigned his position at MAIN and started his own company, Independent Power Systems (IPS), an alternative-energy provider. He kept silent about his former profession, in part because of lucrative favors from old colleagues that made IPS a rare success in its highly risky field, and in part because of not-so-veiled threats from other former colleagues.

Inspired by the native communities that he encountered on his travels in Latin America, Perkins became a champion of indigenous rights and began working with Amazonian tribes to help preserve the rain forest. In 1990 Perkins sold IPS and founded the nonprofit Dream Change Coalition, which encourages people to be more conscious of their impact on the planet and create new, more sustainable ways of living (DreamChange.org). He also became an author, writing The World Is as You Dream It: Shamanic Teachings from the Amazon and the Andes (Destiny Books) and other books that offer a message of hope and renewal. Though he worked periodically on a manuscript about his experiences as an economic hit man, he maintained his silence, continuing to accept lucrative consulting jobs, which he justified to himself by putting the money he made back into his nonprofit efforts.

It wasn’t until September 11, 2001, that Perkins realized he could remain silent no longer. “I knew the story had to be told,” he says, “because what happened on 9/11 is a direct result of what the economic hit men are doing.” He hoped that, if he exposed the system in which he’d once participated, it could still be changed. The book became a number-one seller on Amazon.com, then reached the top of the New York Times nonfiction bestseller list. Despite the fact that the economic hit men are still hard at work, Perkins is optimistic that we can reverse course and create a new system that actually helps, rather than harms, the rest of the world.

For this interview, Perkins and I met at a restaurant on the Intracoastal Waterway in North Palm Beach, Florida. It was a gorgeous day in early December, and boats decorated for the upcoming Christmas boat parade floated by as we talked. Perkins was friendly and forthcoming, and the conversation continued until the sun went down in an orange blaze.

JOHN PERKINS

MacEnulty: Who are “economic hit men,” and what do they do?

Perkins: The term “economic hit men,” as people are using it today, refers to a group of men — and women — who are highly paid professionals working for multinational corporations like Monsanto, Nike, General Electric, Wal-Mart, and many other familiar names. Right now the most prominent of these companies are Halliburton and Bechtel, with their work in Iraq. What these companies and the economic hit men who work for them do is not illegal, for the most part; it should be, but they — we — write the international laws and make these acts legal. I’ve been out of this business for quite a long time, so I can speak only to my experiences in the 1970s at MAIN, not specifically to current activities by the companies I’ve just mentioned.

The goal of the economic hit men is to cheat countries around the globe out of trillions of dollars for the sake of corporate profits. Their job, you could say, is to create a global empire, and they’ve done just that. Not only does the U.S. control world commerce, but we influence world culture: The language of diplomacy and business is English. People all over the planet watch Hollywood movies, eat American fast food, and adopt American styles of clothing. We have no significant competition.

MacEnulty: How exactly do the economic hit men accomplish this empire-building?

Perkins: Through many means: exaggerated financial reports, rigged elections, payoffs, extortion, sex. The game is as old as empire, but it’s taken on terrifying dimensions through the power of globalization. When I was an economic hit man, I traveled around the world and provided “favors” to targeted countries in the form of loans to develop infrastructure — electrical plants, highways, shipping ports, airports, and industrial parks. Of course, all this infrastructure was built by U.S. corporations, so 90 percent of the money never left this country. It was simply transferred from banks in Washington to engineering offices in New York City, or San Francisco, or wherever the corporation was based.

MacEnulty: What role does the World Bank play in this system?

Perkins: The World Bank very much supports the U.S. empire-building project. In doing so, it has betrayed its own founding goals. The World Bank was created at the end of World War II to help reconstruct a devastated Europe, and it accomplished its mission, but then it became politicized by U.S. efforts to fight off the Soviet Union. Today its stated mission is still to help countries build and rebuild, and it has plenty of resources, but it’s gotten off track. I spoke at a World Bank conference two years ago, and I challenged the attendees to do their jobs instead of serving the interests of the economic hit men. There were many young people in the audience who were receptive to my ideas. They had joined the World Bank because they wanted to make the world a better place.

Organizations like the World Bank and corporations like Halliburton are filled with good, capable, dedicated people who are unaware of how they serve the empire-builders. After all, it is easy to hide from the truth: our schools, along with legions of corporate lawyers, psychologists, and economists, constantly tell these people that they are promoting progress — helping, rather than hurting, the world’s poor. One reason I wrote the book is to encourage these employees to look beneath the surface and become aware of what our policies are really doing.

MacEnulty: What’s wrong with developing infrastructure and bringing electricity to underdeveloped areas?

Perkins: Nothing is inherently wrong with it. The problem lies in the implementation. Usually these projects are set up to help industries and big businesses in the countries that undertake them, rather than those who really need the help. For example, in Colombia, we built a dam to produce electricity, but there was a great deal of local resistance to the project. Someone closely connected to rebel forces there explained why: the electricity would help only the wealthiest few, and thousands would be adversely affected because the fish and water and general environment would be drastically changed after the dam was built.

MacEnulty: Aren’t these same rebels also connected to drug lords and terrorists?

Perkins: Yes, and I’m sorry to say that, in a real sense, we pushed them into drug trafficking and terrorism. For if you are a peasant or an indigenous tribesman trying to defend your land against oil companies, lumber companies, or other foreign intruders, the drug trade might well be your only available source of financing. You have to get training and weapons if you want to defend your family against corporate invaders, and you can’t turn to Russia or China anymore. Where else can you go for redress and support: The UN? The World Bank? As a result, we are pushing people right into the arms of criminal and terrorist organizations. Unfortunately, many poor people around the world see Osama bin Laden as a hero because he stands up to the mighty U.S.

MacEnulty: How did the role of the economic hit man originate?

Perkins: It can be traced back to the 1950s, when Iran rebelled against the British-controlled Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, which was exploiting its resources and its people. Mohammed Mossadegh, the popular, democratically elected Iranian prime minister, threatened to nationalize Iran’s petroleum assets. England, looking after its oil company’s interests, couldn’t let that happen, and called on the U.S. for help. But had England and the U.S. taken military action, the Soviet Union might have been provoked to retaliate. So they had to find other means to intervene. That’s when Washington sent CIA agent Kermit Roosevelt (the grandson of Theodore Roosevelt) to Iran. He used payoffs and threats to garner favors from Iranian government officials and incited riots and violent demonstrations to bring down Iran’s democratically elected leader. In his place, the U.S. installed the shah, a dictator. This reshaped Middle Eastern history and changed our approach to empire-building.

MacEnulty: When you were an economic hit man, what was your role in the system?

Perkins: My job was to convince the governments of developing countries to accept loans to pay for projects that we — that is, U.S. corporate interests — envisioned. In essence, I talked them into putting their countries heavily in debt. Henceforth, whenever the U.S. needed a favor, such as an agreeable UN vote or land for a military base, the country’s leaders would not be in a position to refuse. Even if the government changed hands, the loans would still be in place.

There is currently a movement in Latin America against these practices, and some countries are balking at paying off debts incurred by former rulers, saying that the leaders who accepted the loans were puppets of the U.S. and coerced by bankers. In our country, if a banker coerced you to take out a loan you couldn’t pay back, that would be criminal. And many of these countries are now saying just that: “This is illegal.” In the past few years, Chile, Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, Ecuador, and Venezuela have all elected presidents who are vocally opposed to U.S. policies.

MacEnulty: How exactly would you convince a country to take out an exorbitant loan that it wouldn’t be able to pay back?

Perkins: First of all, I didn’t need to convince an entire country — only its leaders. That’s one reason why the system should be illegal: the poor people who get saddled with this huge debt have no role in the decision-making. Many of the leaders are dictators, but even in cases where the leader is democratically elected, people have no control over the leader’s actions until the next election. Ultimately they can throw the guy out, but by then it’s too late, and that’s in the best of cases. Often I had to convince only one or two people, which isn’t hard to do, because the leaders stand to get very rich through the loans. That’s how Ferdinand Marcos got so rich in the Philippines, and the shah in Iran. In Indonesia, Suharto became very rich this way while most of his country’s people lived in abject poverty.

MacEnulty: How do these leaders amass money under this system?

Perkins: First, the infrastructure that gets built — the power plants, harbors, and industrial parks — benefits them directly. In most cases such projects primarily serve the wealthy, the big industries, and the commercial sector, while barely reaching average citizens who most need help.

Second, there’s a system of “legal” payoffs. The way this typically works is that family members or good friends of a country’s top officials might own local equipment franchises, such as John Deere or Caterpillar; or they might own companies that are subcontractors to Bechtel or Halliburton or one of the other designated project managers. Then, when we contract these relatives’ companies, we intentionally pay them more than the going rate. For example, let’s say we wanted to rent John Deere equipment, and we knew it was worth six hundred thousand dollars. We would agree to pay the John Deere representatives in Indonesia a million dollars, and the extra four hundred thousand would go to the government official. If anyone ever questioned it, we could simply say, “We thought a million dollars was a good deal.” There’s nothing illegal about cutting a bad deal.

A third way we enrich a country’s leaders is through favors for family members. When I worked for MAIN, our offices in Boston were filled with the sons of government officials of other countries. We paid their college tuition, their living expenses, and their transportation expenses. We also hired them as interns and gave them generous salaries. All of this was an indirect payment to their fathers — a pure and obvious bribe, but not illegal.

My job was to convince the governments of developing countries to accept loans to pay for projects that we — that is, U.S. corporate interests — envisioned. In essence, I talked them into putting their countries heavily in debt.

MacEnulty: In your book, you discuss how Saudi Arabia became indebted to the United States, and you describe the close ties between the Bush family, its corporate interests, and the House of Saud — the Saudi royal family. It seems that back in the seventies and eighties, your company and others like it actually had plans to raise the standard of living in Saudi Arabia, but now we hear about rampant unemployment there. What happened to all those improvements?

Perkins: Saudi Arabia is a country with tremendous resources. In the early seventies the U.S. struck a deal with the House of Saud whereby they would invest their petroleum profits in U.S. government securities, and our Treasury Department would use the interest from those investments to hire U.S. companies to build a new Saudi Arabia — in essence, to Westernize the country. As part of the deal, the House of Saud would guarantee us an acceptable oil price, and we would guarantee the continued rule of the House of Saud.

We all did as we’d agreed. The U.S. companies produced petrochemical plants and desalination plants, built cities out of the desert, and brought in a lot of cheap labor, because the Saudis claimed they didn’t want to do that kind of work. Many Saudis, however, were opposed to such Westernization all along. Now the country is in social and political turmoil, the House of Saud is in deep trouble, and we deserve a great deal of the blame. Our country has gotten tremendously wealthy, but the average people of Saudi Arabia do not feel they have benefited. In addition, Muslims around the world are angry because the country that is home to Islam’s most sacred sites — Mecca and Medina — has allowed itself to become at least partly Westernized.

MacEnulty: So, in essence, our foreign aid was not aid at all to the majority of Saudis.

Perkins: Exactly. Sadly, that is the norm, not the exception. Foreign aid should go to helping the poor — not just to feeding them, but to helping them feed themselves. When my company went into Panama, General Omar Torrijos, the leader at the time and a very strong one, refused any projects that would not actually help his people. So we did some smaller projects in Panama that really were useful. In particular, we developed some approaches to farming and irrigation that helped small farmers. If you go into places like Panama and work on a local level to create better transportation and small industries and markets, you can do good things. These projects won’t increase the gross national product significantly, but they will improve people’s lives.

MacEnulty: That must have been an eye-opener for you.

Perkins: It was. I’ve since been involved with some nonprofits that promote microbanking, which has been very successful in helping people around the world. Usually it consists of small loans to individual men and women, who open up shops or invest in their family farms. These loans have an extremely high payback rate. I suggested to people who work for the World Bank that they offer microbanking, but they declined, saying it’s too small, their overhead is too high, and their bureaucracy can’t deal with it. So then I suggested that they just supply insurance or a fund for the microbanking nonprofits. But I never got a response.

In my heart I knew what we were doing was wrong, but we were implementing a model that, in theory (especially the theories taught in business school), looked very good. . . . But the model is based on a false premise: that economic development is always good for the majority of the people.

MacEnulty: According to your book, when General Torrijos of Panama stood up to the system, the CIA “jackals” assassinated him.

Perkins: Yes. That can happen. When we economic hit men fail — as I failed with Torrijos — the CIA is sent in. I have an acquaintance who’s one of those jackals I describe in the book; today he works as a mercenary for a private company in Iraq. And he will tell you that when both the economic hit men and the jackals fail, the military steps in.

You see, the economic hit men failed in Iraq. After the first Gulf War in 1991, we thought Saddam Hussein had been sufficiently chastised. But he was just crazy enough not to buy into our development plan for his country. If he had just gone along with our plan, he would still be head of state and have all the weapons of mass destruction he could ever want. But he refused to capitulate, so the jackals tried desperately to assassinate him for years. He had very loyal bodyguards, however, unlike those South American leaders we didn’t like, whose bodyguards had been trained by the U.S. military at the School of the Americas. We couldn’t get through to Saddam economically, and we weren’t able to assassinate him, so you know what happened next.

MacEnulty: You knew the kind of damage you were doing while you were an economic hit man, how many lives were being ruined. How did you justify your actions?

Perkins: I was torn. In my heart I knew what we were doing was wrong, but we were implementing a model that, in theory (especially the theories taught in business school), looked very good. This model held that by building large infrastructure projects, you would increase the country’s gross national product, and everybody would benefit.

But the model is based on a false premise: that economic development is always good for the majority of the people. Like everyone else in the system, I could say, if questioned, “I’m doing what all the models show to be good business. Everybody knows you’ve got to have electricity to make an economy grow.” If you look beneath the surface, however, you can see that the electricity never reaches the rural areas or the city slums. Privately, I was haunted by guilt, because I knew what I was doing wasn’t right.

MacEnulty: In your book, you name a number of people who were your supervisors. Did they have any understanding of the harm they were causing? Do they now?

Perkins: After the book was published, Einar Greve, the man who recruited me, wrote a letter confirming the accuracy of my account. He’s also planning to write a book. I can’t speak for any of the others. They were smart men, so you have to assume they knew what they were doing. But, of course, they were getting rich in the process, being promoted, and leading a good life. I think people go in thinking that they will be helping another country; then they get sucked into the system.

MacEnulty: One of the countries you write about is Indonesia. A friend of mine recently returned from Jakarta, and she described a scene almost identical to one in your book: a woman bathing in one of the canals while, just upstream, someone is defecating in the water. What’s striking — and depressing — is that the scene you describe took place more than thirty years ago, while you were there specifically to help develop that country.

Perkins: It was 1971, and the U.S. was determined to seduce Indonesia away from communism. Accordingly, MAIN’s electrification project wasn’t designed so much to help Indonesia as to ensure U.S. dominance in Southeast Asia. We can see the same dismal scene there today because nothing has changed for those on the bottom of the economic pyramid — except that perhaps they’ve sunk even lower. My belief is, overall, we made the world a lot worse. According to UN statistics, the income ratio of the wealthiest one-fifth of the world’s population to the poorest one-fifth went from thirty to one in 1960 to seventy-four to one in 1995.

MacEnulty: I think most U.S. citizens are in the dark about what is happening in Latin America. We hear about riots, coups, and other unrest, but it’s never really clear — at least, not in the mainstream media — what any of it is about. I remember how difficult it was to get any real information when the U.S. invaded Panama.

Perkins: We invaded Panama with no provocation. Panama had no army and posed no threat to us or anyone else. It was a unilateral decision, condemned by most of the world. Later, when Congress was debating whether to invade Iraq, some law-makers repeatedly asserted that the U.S. had never invaded a country unilaterally and without provocation. But thirteen years earlier, that’s exactly what we’d done. Why did the press not question this assertion?

Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez was democratically elected, but a couple of years ago the U.S. engineered a coup against him and threw him out for more than twenty-four hours. Later, in a national referendum, he was voted back in by the Venezuelan people. No matter how you feel about Chavez, he was democratically elected, and we have no right to meddle in that. Yet we did, and now we say we’re trying to install democracy in Iraq.

MacEnulty: How would you characterize our system of government, not just at home, but abroad? Is it an empire?

Perkins: I would say that the world right now is run by a “corporatocracy,” a close-knit fraternity of people with shared goals. The members of this fraternity move easily, and often, between corporate boardrooms and the halls of government. A perfect example is Robert McNamara: He was president of Ford Motor Company. Then he served as secretary of defense under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson. After that he became head of the world’s most powerful financial institution, the World Bank. People were actually shocked at the time, because it was such a blatant conflict of interest. Now they probably wouldn’t bat an eye.

MacEnulty: What was the result of McNamara’s tenure at the World Bank?

Perkins: It would be difficult to overstate his influence. His greatest and most sinister contribution to history was to position the World Bank as an agent of global empire on a scale never before witnessed. McNamara bridged the gaps between the primary components of the corporatocracy: government, corporate leadership, and international monetary organizations. Over the years, this symbiotic relationship would be fine-tuned by men such as George Shultz, who served as treasury secretary under President Nixon, then became Bechtel president, and then was appointed secretary of state under President Reagan. Now we have Vice President Dick Cheney, with his Halliburton connections.

MacEnulty: And Shultz’s protégée Condoleezza Rice, who served on the board of Chevron, is now secretary of state.

Perkins: That’s the corporatocracy at work. They all serve one another’s interests.

MacEnulty: You say all this economic manipulation of other countries is not a conspiracy, but it sure sounds like one.

Perkins: By definition, a conspiracy is a small group getting together to plot something illegal. The corporatocracy, however, is more pervasive, and what’s being perpetrated is not illegal. It should be, but under current international law, it’s considered altruistic.

MacEnulty: Do you believe the corporatocracy does as it pleases regardless of whether the Republicans or the Democrats are running the country?

Perkins: Yes, the corporate leaders run the system more than the president does. The Republicans tend to be more closely tied to the interests of certain corporations, but the leaders of the corporatocracy will find some way to render ineffective any president who fails to advocate for what they want or who tries to stand in their way.

MacEnulty: And what do they want?

Perkins: Control over the entire world and its resources, along with a military that enforces that control. Additionally, they want an international trade-and-banking system with the U.S. as CEO. They’ve managed to make quite a bit of progress toward these goals in a relatively short time. The American empire is growing. But, historically, all empires have ended disastrously.

MacEnulty: Are we headed for a disastrous end?

Perkins: Not necessarily — not if we change, if we abandon this empire-building route. I have hope that we will be the exception to the historical pattern. The U.S. is steeped in strong principles of justice, equality, and compassion. Look at the Declaration of Independence; I grew up believing in that document. Instead of grasping for the world and its resources like an octopus with tentacles on every part of the globe, we could make our democratic, egalitarian ideals the basis for a positive foreign policy. Currently, twenty-four thousand people on our planet die of malnutrition every day, and thirty thousand more — mostly children — die of curable diseases. We have the power, the knowledge, the technology, and the creativity to turn this disaster around. What could be more rewarding?

I have seen plenty of people who were once a part of our system of corporate control come around and change. When I first started doing workshops about the wisdom of the native people of South America, those who came were mostly from outside the mainstream, but that has changed over time. Now professionals, doctors, lawyers, professors, and even corporate executives come to these workshops. They do it because they want to become better people and to make the world a better place for their children.

MacEnulty: Judging by the last election, it would seem that the corporatocracy is more entrenched than ever and willing to do anything to stay in power.

Perkins: In a way, though, the last election is encouraging: The old guard and the neoconservatives are digging in because they’re afraid. There are many signs that we are on the verge of environmental and economic collapse, and they stand to lose a great deal. Their desperation in the last election implies we’re making headway. Bear in mind, too, that the Democrats didn’t offer a real alternative in the last election — at least, not in the way we relate to the rest of the world.

MacEnulty: In your book you write that Bechtel’s contract to rebuild Iraq is a current example of an economic hit. You actually have personal ties to Bechtel, don’t you?

Perkins: I do. My father-in-law worked for Bechtel for many years, and my wife is a “Bechtel baby” who grew up in Berkeley, California. She was, in fact, working for Bechtel when I met her. My in-laws are quite liberal politically. My father-in-law helped design cities in Saudi Arabia; for him, it was a golden opportunity to do what he loved. He had no knowledge, at the time, of the underlying implications of his work. Many people didn’t and don’t.

MacEnulty: Your book sometimes presents a pretty bleak picture. Writing about the changes wrought by the oil crisis and the lessons the corporatocracy learned from it, you say, “I knew . . . that the corporatocracy, its band of [economic hit men], and the jackals waiting in the background would never allow the little guys to gain control.” That sounds almost nihilistic.

Perkins: It does, doesn’t it? But that was some time ago. As I’ve studied other cultures and learned more about the prophecies of indigenous people, I have come to believe that we do have an opportunity to reverse our course.

MacEnulty: What are these prophecies, and where do they come from?

Perkins: These prophecies can be found in many indigenous cultures around the world, including the Maya of Central America, the Hopis of North America, the Zulus and Bushmen of Africa, the Tibetans, the Balinese, and the Quechuas of the Andes. The prophecies of these cultures all say that we are currently in a period of great transformation, a time when it is possible to change consciousness. We have the opportunity to honor the earth more, to become more compassionate, more just.

MacEnulty: How has humanity strayed so far from its indigenous roots and the wisdom of those cultures?

Perkins: That’s a question I’ve often wondered about. When you work closely with indigenous people who are still living pretty much in their natural state and haven’t been corrupted by our system, you find that most of them live very satisfying and healthy lives. For the most part, they are happy and fulfilled. Why did we leave that behind? I think it’s because materialism is very seductive. When indigenous people see watches, radios, and other objects of our culture, they want them. Really, we humans are all the same: we see bright, shiny things, and we grab for them. I think that, far back in history, some humans began exploiting that seductive quality of material objects in order to gain wealth, power, and control over other people. And that power, too, became seductive. Through our media, through our schools, through almost every aspect of our culture, we are taught that success means having big houses and shiny cars. At some point in our development, that attraction to material wealth made sense, but now I think we’re discovering that it no longer makes sense for us. In fact, our current model is self-destructive: when 5 percent of the world’s population uses more than 25 percent of the resources — and thus creates more than 25 percent of the pollution — the way of life that 5 percent enjoys can’t be replicated elsewhere.

MacEnulty: What are the practical applications, if any, of indigenous spirituality to our culture?

Perkins: The shamans of Latin America teach us that we can shape-shift our world: First you have a dream. Then you make a commitment to the dream. You apply energy to that dream and every day take action of some sort to make that dream a reality. If you do this, then you will make the dream happen. That’s basically what we’ve done in the U.S. over the past century. We’ve created this very prosperous country where we have lots of cars and lots of money to buy things. Now we have to come up with a new dream.

My work with indigenous cultures helped me understand the importance of following your convictions despite possible risks. After 9/11, I realized it was essential that we in this country give up our dream of controlling the world’s resources. And I needed to set the stage by committing to a new dream. The indigenous cultures were very influential in my decision to start writing this book twenty years ago.

We need to recognize that people around the world are abused and enslaved by our system. All empires are built on some form of slavery.

MacEnulty: Would you call the actions of our leaders “evil”?

Perkins: I don’t believe in evil as an “objective” outside force. Many people are misguided — sometimes deranged — but in my work with corporate executives, I haven’t met any I would call “evil.” Almost all of them want to see a better world for their children, but they don’t know how to create it. Often their solutions to problems create more problems. They’re stuck in one paradigm of thinking. It’s similar to the Middle Ages, when everyone thought the sun revolved around the earth; it was difficult for them to imagine it any other way. The only way to create change is to step out of the old way of thinking. And I think that is what’s starting to happen. I think 9/11 had a profound impact — one we have not yet fully understood — and that the American people are now ready to face reality and make changes.

MacEnulty: What sort of changes?

Perkins: In the book I go into detail about specific things we can do. Each of us has to pick the particular actions that suit him or her best, but we all must remember one thing: that civil movements create change. We need to be involved in these movements, whether they be environmental, anticorporate, animal rights, or any other progressive cause. In this way we have managed many times to create change: women’s right to vote, civil rights, saving endangered species, cleaning up polluted rivers — the list is impressive. It is important, as well, to remember that the American Revolution was started and sustained by people meeting in taverns, organizing the Boston Tea Party, reading the Declaration of Independence and Tom Paine’s Common Sense to one another. George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were traitors to the British Crown. Had the British won, they would have been hanged as terrorists.

MacEnulty: What about the so-called anarchists who protested in Seattle when the World Trade Organization met there in 1999?

Perkins: I wouldn’t call the protestors “anarchists” — at least, not most of them. I see them as part of a movement that gets us to question the motives of the global economic institutions. Any movement that does that helps strengthen democracy. A democracy is built on people speaking out and asking questions.

In a way, we all have to take responsibility for the state of today’s world, including the terrible tragedy that occurred on 9/11. We need to recognize that people around the world are abused and enslaved by our system. All empires are built on some form of slavery — no matter what name you give it. As a result of our policies, there is a groundswell of anti-American sentiment around the globe. No terrorist organization can exist without popular support. Much of the world is very angry at us now, and we need to understand that anybody who strikes out against us may be widely admired.

By definition, a conspiracy is a small group getting together to plot something illegal. The corporatocracy, however, is more pervasive, and what’s being perpetrated is not illegal. It should be, but under current international law, it’s considered altruistic.

MacEnulty: How do you know this?

Perkins: I travel a lot, and I talk to people on the streets. When I go into the Amazon, I hear from the indigenous people there that they have declared war against U.S. oil companies. Already they’re being accused of having connections to al-Qaeda. The oil companies have large armies of mercenaries, and any tribe that goes up against them will, unfortunately, have to turn to the terrorist organizations for help. It is up to us to change this.

MacEnulty: Why are the indigenous people resisting the oil companies? Doesn’t the presence of oil offer them the possibility of great wealth?

Perkins: Just the opposite, I’m afraid. There could be a lot of oil in the Amazon Crescent, which stretches from Venezuela to Bolivia. Some speculate that the area contains an oil reserve as large as some of those in the Middle East. In these areas the local governments traditionally have had very loose environmental laws, so the oil companies can cause an incredible amount of pollution with no fear of consequences for themselves. To get the oil out, they have to build pipelines, which break and cause tremendous damage. Texaco, for instance, has spilled more oil in the Ecuadorean Amazon than was spilled in the Exxon Valdez accident. When rivers are covered with oil, the food supply is destroyed, and animal life is devastated.

In addition, the oil companies bring in roads, and poor people from elsewhere in the country travel those roads into the jungle and become squatters. They try to farm the land, but the jungle soil won’t support crops, so they fail, and they move farther into the jungle, following the oil-company roads, and try again, destroying more and more jungle as they go. In the process, the indigenous people are pushed aside, their lands and cultures shattered.

MacEnulty: So who is fighting back?

Perkins: Two groups of indigenous people, the Shuar and the Achuar, have said they will fight to the last man to keep the oil companies out. Right now, there are legal battles taking place in Quito, the capital of Ecuador. But in the meantime the oil companies are hiring indigenous leaders as “consultants,” translators, and so forth. They pay them a few thousand dollars — a fortune where they live — and ask them to convince their people to accept the oil company’s presence, even though doing so will ultimately destroy their culture. The companies use the same old tricks we used with the indigenous peoples in the U.S.: then it was about land; now it’s about oil.

MacEnulty: A company that can hire a small army must be a formidable opponent. How can the indigenous people — or anyone concerned about the situation — fight it?

Perkins: One lesson the environmental movement has taught us is that corporations are vulnerable. A couple of years ago a major environmental group went up against a multinational corporation. The group launched a boycott of the corporation, and the corporation eventually came around. Not long after that, I was at a conference attended by both the leader of the environmental group and the head of the corporation, and one night the three of us wound up in the hot tub. I was extremely interested to see how these two would interact. To my surprise the corporate executive said to the activist, “Thank God you did what you did. I knew what we were doing was wrong, but I couldn’t do anything about it for fear of losing my job. After the boycott, I could go to our board and push for us to do the right thing.”

In our corporations, you see, there are people who are just as concerned as you and I. They’re concerned for the sake of their children. We need to motivate them to do what they know is right. We need to provide them with reasons for change that they can bring before their stockholders and boards of directors.

MacEnulty: But you’re looking to change an entire cultural outlook. Many Americans admire Donald Trump simply because he has a lot of money.

Perkins: What’s required is a fundamental change in how we view the world and in the values we transmit to our children. We need to teach children that the ultimate goal in life is not to own a private jet. Our expectations are unrealistically high. For some reason, stockholders no longer expect reasonable returns on their investments — they expect windfall profits. In an indigenous culture, by contrast, profit is not a goal. Sure, you might set aside something for the dry season or the cold season, but that’s not the same thing as our imperative for profit. If we’re to succeed as a species, we’ll have to get rid of this expectation of excessive profit. A reasonable return on investment should be satisfactory.

MacEnulty: Is that kind of change feasible?

Perkins: I believe so. Throughout most of my lifetime, the U.S. devoted billions of dollars to the defeat of communism, but that’s not what brought down the Soviet Union. It was a shift from inside, inspired by poets, playwrights, and labor leaders. I think we’re on the verge of a huge shift in consciousness. People are searching. We have to remember, though, that it takes time for change to occur.

MacEnulty: You have acknowledged your own complicity in the systematic impoverishment of Third World countries. Have you done anything to atone for the mistakes of your past?

Perkins: I am devoting my life to changing the situation. In the 1980s I founded and ran an alternative-energy company that helped strengthen U.S. antipollution laws. In 1990 I made a commitment to try to reverse the destruction of the Amazon. I started the Dream Change Coalition, a nonprofit organization that works with indigenous people around the world to help them preserve their environment and their cultures. Unfortunately, a tremendous amount of damage has already been done. When you fly over the jungle, you can see the line of development moving ever deeper. When my daughter came with me the last time, she was crying as we stepped out of the plane into the rain forest; she hadn’t seen the jungle in six years, and the change was so dramatic. It is terrible, but I think we’re making headway. It’s like in Alcoholics Anonymous: We’ve taken the first step and admitted there’s a problem. Now we have to take the other eleven steps.