I was born and reared in southern Illinois, in a rural community so small that by the time the back of the bus entered town, the front of the bus was already leaving it. I was exposed to country music at a young age through my father’s record collection: Hank Williams, Eddy Arnold, Lefty Frizell, Merle Haggard. Their tunes and stories captivated me, and by the time I was fourteen I had written ten or eleven songs that I sang around the supper table and at our local pool hall.

I knew that the music I loved came from Nashville, Tennessee, so after high school and a number of dead-end jobs, I packed up my guitar and suitcase and hitchhiked down to Music City.

Twenty-five years and a hundred songs later, I’m still on the outside looking in. I live on Music Row in a cockroach-infested apartment with no heat or air conditioning, and I spend all my money on demos and food. I have sold my blood at the Church Street plasma center to feed my songwriting habit.

I’ve never had a song recorded, though I’ve come close a few times. It could be Music Row politics, or my lack of contacts, or the changes in the industry, or bad timing. Or maybe my songs just suck. My family says my songwriting dream has destroyed my life, and I admit there are times when I wish I had never listened to my daddy’s record collection. But then again, there was nothing for me to do in my hometown. I would rather be one step away from the gutter in Nashville than living a comfortable life back there.

Years ago, during a late-night songwriting session, a fellow writer told me, “You have to want this more than you want to be loved.” I didn’t understand him then. I do now.

Kim Harold Burns

Nashville, Tennessee

I moved to Paris when I was nineteen with the goal of becoming an actress or a model. I’d already been rejected by several New York City modeling agencies, but I wasn’t going to let that stop me. I’d studied acting, dance, and voice. I was pretty and on the tall side at five feet nine — though not tall enough by New York standards. At 132 pounds, I wasn’t as thin as I needed to be either, but I was working on that.

I had an agent waiting for me in Paris. Well, maybe not waiting, exactly. While having dinner at a close friend’s house, I’d hit it off with her father’s visiting colleague, whose brother François was a casting agent in Paris. I got his number, packed my suitcases, and headed for France.

It all went well at first. I slept on the floor at a good friend’s apartment, in a tiny room that smelled strongly of tea and soap. Every day I walked for hours through the cold gray city, practicing my high-school French. I sat in real French cafes, drinking grand crème and smoking cigarettes, and I went to parties where I was surrounded by glamorous, creative people.

François was working on a television project that he said would be the first French miniseries. The star was the aging singer Johnny Hallyday. I was to be an extra in a bar scene. I arrived at the studio early and, after hair and makeup, moved to the soundstage, where the other extras and I were placed around a bar facade. Johnny Hallyday’s arrival on set was greeted by an awe-filled hush. The filming was just as I’d imagined, with the director yelling, “Cut!” — only in French. He yelled it quite a lot, as Hallyday had difficulty remembering his lines.

After my successful turn as an extra, François gave me the name of a talent agent, whom I met with in a blindingly sunny office on the Rue Marbeuf. He nodded approvingly at me and got me a job performing at a shopping mall in the northern suburb of Sarcelles: six girls parading through the mall to promote a live race-car demonstration on the promenade. The event ended in a disaster when the race car lost control and swerved into the crowd, injuring several onlookers.

Next I auditioned for a TV show. When I discovered that the script called for me to flash my breasts, I only mimed exposing myself for the production staff. I didn’t get called back.

Then my agent sent me to try out for a necklace advertisement, but the woman across the desk coldly observed that I seemed to have gained some weight since my pictures had been taken. You see, I’d discovered that the corner market near my new apartment sold Milka, my favorite chocolate bars, by the three-pack. They’d become a staple in my diet.

As my social life slowed to a crawl, I stopped marketing myself and instead read Nabokov novels and ate Milka, reveling in its heady, velvet sweetness. I slept on a thin foam mattress and woke in the morning to stare at cracks in the ceiling and the mess of lilac-colored candy wrappers on the floor. I sometimes rallied and took a walk in the Paris air, but the glimpses of other people’s glamorous lives only left me feeling more adrift.

I began dating Adrien, a photographer I’d met on the race-car job. He was wonderful company but smoked too much pot and always looked emaciated. We had little money, and I had to scrape together my centimes to buy a baguette and a small jar of Nutella. Otherwise I would go to Adrien’s apartment and eat his roommate’s food.

Deciding I needed a change, I cut my hair myself. It came out short — very short — and patchy in the back. It did not look good.

Adrien and I parted ways. My agent stopped calling. My father’s most recent wire transfer — which I’d assured him would be the last — had run out. I was overdrawn at the Crédit Lyonnais. I found a job waitressing at a macrobiotic restaurant, but I couldn’t understand the Japanese cooks, and they couldn’t read my handwriting on the orders. After two shifts, I admitted defeat. Some Italian girls let me sleep on their sofa, and I spent my days cutting pictures from old fashion magazines. Twenty-five pounds heavier, my shorn hair growing back unevenly, I flipped through the glossy pages and ached with desire for what I somehow still believed could be mine.

Miranda Hersey

Groton, Massachusetts

My second-generation Italian American parents wanted me to be a doctor. It was the only profession that would have made them proud. My mother even told her friends, before I’d selected a college major, that I was going to medical school.

When I announced to her and my father that I was studying to become a geologist, she asked, “What is that? A foot doctor?”

My father corrected her, telling her — with a wink in my direction — it was a type of gynecologist.

No, I said, geology had nothing to do with medicine. A geologist studied the earth, rocks, and minerals. My mother was crushed. “Why would you want to do that?”

Over the next four years, I tried to convince my parents that geologists could earn fame, if not fortune: the geologist Harrison Smith had walked on the moon during the Apollo 17 mission. My parents spent those same years trying to turn me away from geology, the way other parents might try to persuade their son he isn’t really gay. They talked to our parish priest about my choice, encouraged me to spend time at the hospital with my cousin Tony “the neurosurgeon,” and showed me pictures in Life magazine of smiling young doctors.

Even after I’d graduated with my degree in geology, my parents weren’t defeated. They started telling family and friends I was an archaeologist, and that my work took me to remote parts of the world in search of rare artifacts. In reality I worked in Montana, looking for gold deposits. When I returned home for the holidays, relatives would ply me with questions about my travels to Peru and my plans to write a book about my adventures.

At first I tried to put down these rumors. But after a while I realized I had nothing to gain by calling my parents liars. So I made up wild tales about excursions to Outer Mongolia and the Amazon. My latest “book” is about the pre-Neolithic sites I discovered in central Africa — while escaping from cannibals.

Thomas Cammarata

Seattle, Washington

A week before I graduated from college, my dad won several million dollars in the state lottery. I went out to celebrate with friends, and we threw dollar bills into the air and watched them spiral down with the falling flakes of snow. I remember thinking how different everything would be from then on.

My dad had spent his whole working life tending bar and cooking at the small restaurant he owned. He wore a prosthetic leg as a result of a birth defect, and all those years on his feet had been hard on him physically. One of the first promises he made after his big win was that he would pay for any further education my siblings and I wanted.

Requests for money poured in from people we knew, and from some we didn’t. Within a year the notoriety had become overwhelming, and my dad and stepmother moved from the small community where they’d lived for twenty years to a place where no one knew them. Instead of pouring beers, my dad spent his days grooming his yard, tending to his pool, and pampering his new dog.

Tensions arose between my dad and relatives who expected handouts. Money became a sensitive subject between him and me as well, and after a few arguments I learned not to expect anything, even when I moved to a new city with only five hundred dollars in my pocket.

It’s been ten years since then, and I hardly think about the lottery money anymore. For all I know, it’s gone. I have learned to be self-sufficient and am going to graduate school for expressive-arts therapy, paying for it through student loans and scholarships. After many years of being withdrawn from society, my dad is now reaching out and counseling people who’ve lost limbs — most recently, soldiers returning from Iraq. He just came back from an amputee convention, where he ran a road race and took dance classes. I am proud of my father and know he is proud of me. But I still miss the way things were before.

Name Withheld

A small group of women friends and I gather every autumn for a writer’s retreat in a remote corner of northwestern Montana. We are teachers, housewives, and artists who love to read and write. None of us is famous; none of us is rich.

It is a rugged retreat: no makeup, no bras, no husbands or kids, and no agenda other than daily writing. Each of us has her own cabin overlooking the river, with a bed, a table, a chair, and a wood stove that we have to feed in order to stay warm. We read and write by candlelight and even use an old-fashioned outhouse that leans ever so slightly. In the evening we gather to eat, drink wine, and share what we’ve written (or not).

One afternoon when the weather was glorious, we gathered on the banks of the river for our midday meal. But there was one woman whose mood wasn’t in sync with the day. During her morning writing, she’d had a crisis of confidence. If she was ever going to become a famous writer, she said, she should have at least had some success by now. Her eyes filled with tears.

Like a Greek chorus, the rest of us reassured her of her brilliance, showered her with comforting platitudes, and reminded her that, to us, she was already wildly successful. She seemed comforted and even laughed a little.

As I walked back to my cabin, I felt my own seeds of doubt. I wasn’t rich or famous either. My mark on the universe was no more significant than that of the fly buzzing around the sun-warmed glass of my cabin window. I spent the afternoon fighting back the tide of my own uncertainty. I told myself everything I had said to my friend a few hours earlier. I cried, then slept.

That night we gathered around the campfire. Someone passed a bottle of tequila, and we sang songs, laughed, and even howled at the moon. Snowcapped mountain peaks loomed in the moonlight, and my earlier doubts slowly faded. The quest for fame and fortune seemed unimportant — for that night, at least.

Julie Greiner

Kalispell, Montana

When I was five, my mother began regularly telling my older brother and me that she was going into our bedroom to write and wasn’t to be disturbed. (I don’t know why she chose our room in which to work.) She said she was writing a novel about the end of the world, and we should prepare for her to be away a lot after she became famous. My brother and I didn’t even know what a novel was.

The largest item in our crowded bedroom was Mom’s writing desk: a squat wooden work table of the sort a graphic designer might use. It looked ugly to me. Mom labored there on her novel day after day, and we tried not to disturb her. I don’t remember what we did while she was shut in our room, but somehow we didn’t feel too alone; we had friends in the neighborhood whose mothers were more available.

Mom worked on that novel for more than fifty years. It went through endless revisions and was rejected by seemingly every publisher in the English-speaking world at least twice. Mom sometimes showed us her growing stack of rejection letters, as if they were evidence of her progress.

For her seventy-fifth birthday, I created a website for her novel, posting the unintelligible first chapter. I had one of her friends show her the website, on which the novel’s title was rendered in moving red flames. Mom was pleased to be “published” at last. I even sent her some phony fan letters that I wrote. Mom is eighty-eight now and nearing the end of her world. She has never discovered my deception.

Name Withheld

My father owned a small grocery store in the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York. Despite his lack of money and social status, people were drawn to him. He had an understated charisma, due in part to his absolute lack of concern for wealth and fame. When a well-known author, who had taken to eating lunch on the store’s porch, had a book reach number one on a national bestseller list, my father’s only comment was “You switching from bologna to boiled ham now?”

If anything, Dad was a reverse status-seeker, always avoiding the spotlight. He would hate that I am writing this, but he’s been gone a long time. Whenever I see someone from my childhood, we end up telling stories about him.

One year, for my father’s birthday, a prominent multimillionaire who summered in our town sent a gift of Indian Pipe Madeira wine, bottled in the early 1800s. My father never opened it. Another wealthy vacationer brought the crown prince and princess of Liechtenstein to my father’s store to meet him. To my dad, they were simply a couple of “summerfolk.”

Once, the CEO of Tetley Tea came to our home and sat on the back steps with my father, who took the opportunity to point out that, in his opinion, their tea bags were too small. A short time later that CEO sent my dad a case of teapot-sized tea bags. Those my dad did open.

Catherine Holmes

Loudonville, New York

One of the many things my first husband couldn’t stand about me was my unshakable belief that my children and I were uniquely gifted individuals. “Why do you think you’re so special?” he would ask, usually when he’d been drinking.

I believed that he was special too, of course — at least, at first. I’d worked hard to put him through medical school. I thought he was smart and talented and would bring our family wealth and status in the community. (I never questioned whether wealth and status were really what I wanted.)

Unfortunately my husband’s bipolar disorder and alcoholism both went untreated until long after our divorce. My children did grow up to do extraordinary things with their lives, and I got a PhD. It turned out we didn’t need to bask in his glory. We earned our own.

C.D.

Gladwin, Michigan

In a small town, I discovered, a person can become famous just by teaching high school. At work I was just Ms. O’G., but outside the classroom — at the store, the gym, a restaurant — I was a celebrity. My male students would smirk when I purchased tampons at the grocery; my female students would shriek when I came out of the shower at the Y wrapped in a towel. Reports of my menstruation and cellulite ran rampant.

On the first anniversary of my mother’s death, I planned to drink a beer and smoke a cigarette in her honor. I don’t often drink, and I’m rabidly antismoking, but my mother had been just the opposite, and I was feeling nostalgic for the scents of my childhood.

I stopped at the local gas station to get a six-pack and some cigarettes. On my way out, I ran into Jay, a former student of mine who was now a senior. Like a movie star surprised by the paparazzi, I was caught, beer and Marlboro Lights in hand.

“I can’t believe you just bought cigarettes,” Jay said.

I often lectured my classes on the evils of smoking. I bad-mouthed cigarette companies and impressed the kids with my ability to distinguish a student who smoked from a student whose parents smoked just by sniffing their jackets.

Jay’s initial shock turned to disappointment. “Damn, Ms. O’G. The beer, OK. I get that. But cigarettes. Damn.”

My little private party — just me and my complicated relationship with my mother — had been crashed by my public persona.

I’ve since quit teaching. The last of my former students are finally leaving town or else adjusting to finding me next to them at the gym, or the bar. I like being anonymous again.

Mary Ann O’Gorman

Ocean Springs, Mississippi

I used to pee on a man for money. It wasn’t very much money, but there was also free liquor and all the cocaine I could ever want — piles of it by the bed. There was another man who liked for me to hang out with him in the nude. He would always tell me that the next time he was going to fuck me, but this time he just wanted to look at me and talk. He paid me a thousand dollars an hour.

Some men wanted me to bring a friend, so they could watch. The friend and I would put on a good show. (It isn’t hard to fool a horny man.) So I suppose that I was an actress of sorts, and I did achieve a certain fame, although not one that I will tell my children about. But I never accumulated any sort of fortune; all the money I made, I spent trying to forget how I had earned it.

Those men each had different reasons for wanting my services, but they were similar enough in many ways: they were all rich, all powerful in business, all well-known, and all chasing the dream of the eighteen-year-old girl and everything her young body offered and promised. And no matter what I did for them, not one of them could ever get it up.

Name Withheld

“Dad,” I say, “I need a shovel for my garden.”

“Go check the shed, honey,” he replies.

I walk toward the old shed in the backyard, wondering how many years it’s been standing. A loose board tilts sideways. I lift a wire latch, and the door falls off the one hinge it has left. Inside I find three rusty shovels, plus two more with no handles, and another two stuck in dried mud. All seven are buried in junk my father will never get around to throwing out. I walk back to the house, shovel in hand, feeling sad.

I tell my father the shed needs to be cleaned out. “When’s the last time you were out there?” I ask.

My father looks at me with a blank stare I have begun to recognize. “I guess it’s been a while, honey.”

I sigh. “Well, Dad, I found seven shovels out there. What do you think of that?”

He smiles and says, “We’re rich.”

Jane R.

Brunswick, Maine

When my first young-adult book sold, the editor at the publishing company called me with the good news. She praised me, saying that I was going to be famous one day. After I’d hung up, my husband told me I’d said, “Wow!” at least ten times. All my life I’d wanted to be a published author, and now I’d finally accomplished my goal.

By the time I received the galley proofs, I hadn’t looked at the manuscript in four years. I expected to read the “wonderful” book my agent had praised, but it wasn’t wonderful. It was clunky and stupid. I secretly no longer wanted any part of it.

My co-workers at the school where I taught complimented the book, but one person, a real intellect, passed me in the hall and said with a sneer, “I read your book.” That was all. I was deeply embarrassed.

A friend of mine borrowed a copy and returned it badly water-damaged. It had fallen in the toilet — in clean water, she said. I was horrified, but deep inside I believed that was where the book belonged: in the toilet. I felt as if its publication had exposed me as the not-so-talented writer I was.

I refused to do any author signings, and the book didn’t sell well, but it did get printed in two foreign languages. I was pleased when I received the foreign editions, because I couldn’t read them. I could just hold the books and feel OK.

One night I got drunk and reread my little book from cover to cover. Perhaps it was the alcohol, but I went easy on myself and thought, I did a good job. It was the best I could do at the time. I held the book to my chest and cried.

Ann Garcia

Hillsboro, Oregon

When I see the woman standing in an aisle at the dollar store, I think I know her, but I can’t say from where. Suddenly she bursts into tears, hugs me, and says, “Thank you so much for being kind to my husband. You made his last day on earth the best it could be.”

Another time, a recovering alcoholic credited me with convincing him to stop drinking. This minor fame I enjoy as a nurse is not the kind I dreamed of when I was a kid. Back then I was going to become a famous author. I’d write my first novel by the time I was thirteen and win a Pulitzer Prize by twenty-five. Then I would put my fame to good use in some Third World country. I might even win the Nobel Peace Prize — probably by thirty-five.

With my fiftieth birthday only a few months away, I’m starting to acknowledge that there won’t be a Pulitzer or a Nobel in my future. I’m at life’s great divide, where I simultaneously believe anything is possible and realize that this is it: this is what I’ve done with my life. I know I could still do something world-shaking, but I also know that I won’t.

I like the simple, comfortable life I’ve created. The important thing is not how many people know you, but how highly they regard you. I’m known, to a small circle of acquaintances, as compassionate and loving. And I get invited to more potlucks than I can possibly make casseroles for. That’s fame and fortune enough for me.

Lauri Rose

Bridgeville, California

In the summer of 2001, the little biotech company my husband had started as a “hobby” after retiring from academia was bought by a major firm. We went abruptly from being upper-middle-class to being rich — hugely rich. When I got the news, I was shaken and felt strangely terrified. A vision of the future hit me: gold diggers trying to marry our children; our future grandchildren self-indulgent wastrels; and my husband and I, like lottery winners, broke, divorced, and alcoholic five years down the road.

At first I pretended the money didn’t exist. I was determined to keep buying my clothes at discount stores and driving my battered station wagon. I vowed never to retire from the job I loved. I felt unentitled to such wealth, and I wondered whose good luck I had stolen.

Then came my first lesson of being rich: money makes things possible.

Ever since our son had been little, he and my husband had loved hiking in the woods around our house. On one of their rambles that year, they were horrified to find orange surveyor’s ribbons marking off a large tract in their favorite wooded locale. The next day my son and I went downtown and learned that the land was being sold to a developer and would become an upscale residential subdivision. The bulldozers were set to arrive in two weeks.

My son and I were both in tears. Could anything be done? Of course: all we had to do was offer the seller more than the developers had promised, and the real-estate deal would be off. We did, and the owner sold us the property, which we promptly donated to the local land trust.

We discovered we enjoyed philanthropy. We started by giving 10 percent of our income each year. But we couldn’t ignore President Bush’s monstrous tax cut for the rich, so we calculated our tax windfall and gave it to charity too. Then we calculated how much our charitable contributions reduced our tax bill and added that amount to the tithe. My husband was eligible for Social Security, but it was unthinkable for us to accept money from that struggling agency. So we added that money into our charity pot. In all, these calculations yielded a “tithe” of about 20 percent.

So how rich are we, really? Compared to the other 6 billion people on earth, we are in the top .001 percent. If we had lived during the French Revolution, Robespierre would have lined us up for the guillotine, and who could have blamed him? But among moneyed Americans we barely even rank. The five hundred wealthiest Americans are all multibillionaires. Compared to them, we are middle-class.

I favor higher taxes on large incomes and estates and wish the U.S. had Sweden’s system of social welfare. But it turns out (and I feel sheepish admitting this) that I love being rich. The first year, we paid off our mortgage, our kids’ mortgages, our kids’ student loans, and all the credit cards. Our special-needs grandchild gets whatever therapy he requires without a second thought. We have discovered the thrill of overtipping and even funded early retirement for my husband’s ex-wife.

Our marriage is happier now than it has been in all our thirty years together. My theory is that most marital altercations, however well disguised, are about money. When you have so much of it that you don’t need to worry about it, you stop picking fights over other matters. In our prewealth days, we used to nag and snipe at each other about household chores. Now we have a full-time employee to take the car to the mechanic or the cat to the vet; to fix our Internet connection or the leaky roof above the guest bedroom. We pay him a handsome salary, plus benefits, and he loves his job.

We’ve also discovered the joy of getting rid of things. Why, I wonder now, did I hoard all those clothes I never wore? Did I really enjoy having my refrigerator overflow with spoiled leftovers? No, I did these things out of guilt over “wasting” money that had already been unwisely spent.

After our financial windfall, I kept working for five more years. Deciding to retire at sixty-two was tough, just as difficult as making up my mind to divorce my first husband had been. I steeled myself for a transition filled with regret, sadness, and loss of identity. But I experienced none of that. These days I write, paint, and travel to workshops on writing and painting. I take my grandchildren to the zoo. I read literary magazines and political blogs. I have stimulating discussions with friends. I grow and cook my own vegetables. I am working seriously on reducing my carbon footprint. For the first time in forty years, I’m not sleep deprived. For the first time since fifth grade, I get regular exercise.

I’ve been poor, and I’ve been rich. And yes, I can honestly say that I’d rather be rich. Who wouldn’t? But I believe that, rich or poor, we can all live generously, discuss money honestly with the people we love, and stop feeling senseless guilt over our past decisions.

I hope I remember these lessons if I lose everything.

Alice A. Chenault

Huntsville, Alabama

On the afternoon of my sixteenth birthday, I started waitressing at a Friendly’s restaurant near my home in Baltimore, Maryland. After being trained in the fine art of order taking and ice-cream scooping, I was ready for my first customer. I nervously approached the man at table 7. “Hi, my name is Laura,” I said. “I’ll be your server today. What may I get for you?”

When he looked up, I realized it was Mark Belanger, the shortstop for the Baltimore Orioles. I was an avid Orioles fan and could barely contain my excitement.

He ordered a hot cocoa. Awe-struck, I prepared his drink and carefully balanced it on my tray to serve it to him. Moments later I was spilling hot cocoa all over Mark Belanger’s lap. I apologized profusely and hid in the kitchen for the next half-hour.

When I emerged, he’d left me a five-dollar tip. Scrawled across a cocoa-splattered napkin was his autograph.

Laura Howell

North Andover, Massachusetts

My four-foot-ten-inch grandma, with her fourth-grade education and heavily accented English, worked at a newsstand on 45th Street and Lexington Avenue in Manhattan. She woke at dawn and traveled an hour by subway to get there. In winter she wore long underwear, three sweaters, galoshes, and fingerless gloves. She never mentioned the cold.

Each night when I was a girl, Grandma and I would sit at the kitchen table in our Bronx apartment and discuss how I would become a singer and dancer someday, the next star of stage, screen, and television. Grandma would sip her coffee, and I’d dunk my graham crackers in milk while deciding which songs I would sing, what sort of dresses I would wear, and on which TV shows I would appear. (We both agreed The Ed Sullivan Show had to be the first.) After I became famous, Grandma would be my manager, and we’d rent an apartment together on Fifth Avenue or Central Park West. We’d each have our own bedroom suite but would share a living room and a kitchen. (I adored her cooking: kreplach, chicken soup, brisket with potatoes and carrots, and kasha varnishkes.)

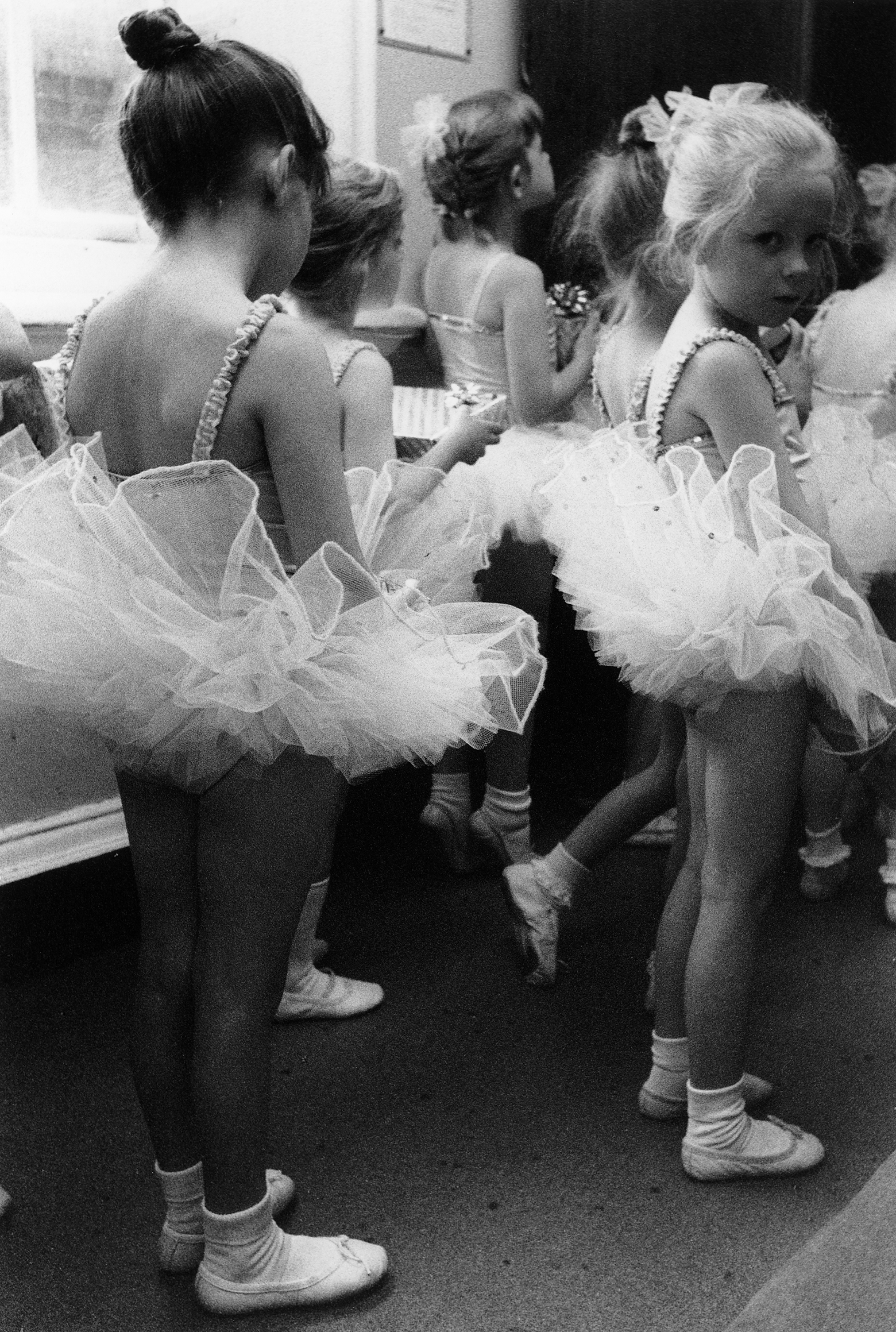

My dream of becoming a dancer never faded. Each Halloween I was a ballerina in a stiff powder blue tutu, a winter coat thrown reluctantly around my shoulders. I attended classes twice weekly at Marjorie Marshall’s School of Dance, in the basement of an apartment building. There I learned tap, toe, ballet, and acrobatics, and also received voice and diction training. At fourteen I joined a professional modern-dance company, and a year later I was accepted at the School of Performing Arts. I went on to perform at Lincoln Center and Carnegie Hall, but I never became wealthy or famous.

Now retired, I no longer want fame and fortune, but only peace and quiet. I wake each morning, move through my yoga poses, and sometimes think of my grandma.

Karen Marcus

Ringwood, New Jersey

I was once a morning-show disc jockey on a country-music radio station in south Texas. My cohosts and I had the most popular morning show in the area. We made regular public appearances, and I was sometimes going strong until midnight — then getting up at 4 A.M. the next day to do it again. I was newly divorced, I had just turned thirty, and I could do anything.

I got recognized everywhere in town. I went to the front of the line at concerts, had my picture taken with visiting celebrities, and often got meals for free when restaurant managers found out who I was. I made more money than ever before, but I also got myself into debt.

I wasn’t cut out to be a star. I always felt funny when I was asked to sign an autograph, and the adoring looks I occasionally saw in fans’ eyes made me squirm. Didn’t they know I wasn’t really the wisecracking character they listened to on the radio? It was just show business. I found myself resenting their ignorance. It got harder and harder to get out of bed at 4 A.M.

After three years at that job, I met the man who became my husband, and we moved to southern California. By then my energy was depleted. Fearing that my husband expected me to continue being the lively, vivacious radio personality he’d married, I tried to keep up the charade, but after several months I crashed — emotionally, physically, and spiritually.

I am fortunate. My husband hadn’t fallen in love with the radio personality. With his support, I got some help, and I’ve learned to be who I really am: just a girl who grew up on a dairy farm in Michigan.

Heidi Wassermann

Alpine, Texas

I grew up in Pennsylvania, and my father used to go to New York City on business trips. Once, he told me this story: At a three-martini business lunch, someone said to him, “Churchman, why are your clothes always so baggy?” And he answered, “Because I am a bigger man in Philadelphia than I am in New York.”

Twenty-seven years ago, three gay male friends, my girlfriend, and I decided to move from Philadelphia to New York City. We were going to make it in show business as a gay musical-comedy act. It took us all day to fill the U-Haul — not a van, but a giant truck — with boxes, furniture, and costumes.

It was well after dark by the time we drove out of Philadelphia on the Benjamin Franklin Bridge. From high in the cab of the truck, I could see the steep drop into the black water of the Delaware River. My muscles were like jelly from lifting boxes all day, and my skin was stiff with dried sweat and grime. I looked back at the lights of Philadelphia stretching out behind us, and I realized that, at that moment, I lived nowhere. I was suspended between what I’d been — a baby ballerina, a prep-school misfit, a Super-8 filmmaker, a waitress, a secretary, a horse-show groom — and what I would become: hopefully a star.

The act broke up a few years later. It was painful and messy. I didn’t become a star, but maybe I will someday. I’m still with the same girlfriend, and I’m still in New York.

Paige Churchman

Brooklyn, New York

When I was ten I wanted to be rich and famous so I could do whatever I wanted, and nobody could say anything about it.

I’ve had small tastes of fame, but I haven’t become rich. Or maybe I have; it depends on how you measure wealth. I have a twelve-year-old daughter, and I’ve stayed home to raise her because I want to. I have a husband of fifteen years who shares my life and has fathered our child well.

The longer I continue this alternative accounting, the more the riches pile up: A fig tree that feeds me every July. A sandbar that I can sun myself on in the fall. The love and respect of friends. Closets full of vintage clothing. Memories of good times and bad. Shelves of books mostly read and enjoyed. A cypress planted thirty years ago, now grown into a stately shade tree. Blackberries mingling with wild roses along the fence.

Sandy Carter

Goodrich, Texas

Elena moved in with me when I was on my way up. I soon became rich, but then the market turned. I was OK for the moment, but a good friend lost everything. When he announced his new poverty to his girlfriend, she asked whether it would affect their vacation to Puerto Vallarta.

Seeing my own financial ruin on the horizon, and nothing I could do to stop it, I told Elena that it was all right for her to leave.

She looked at me quizzically.

I said that I understood this wasn’t the relationship she’d signed up for.

She told me it wasn’t time for her to go; it was time to circle the wagons.

We were homeless for several months. Twenty-two years later, she is still lying beside me.

James Bellevue

Austin, Texas