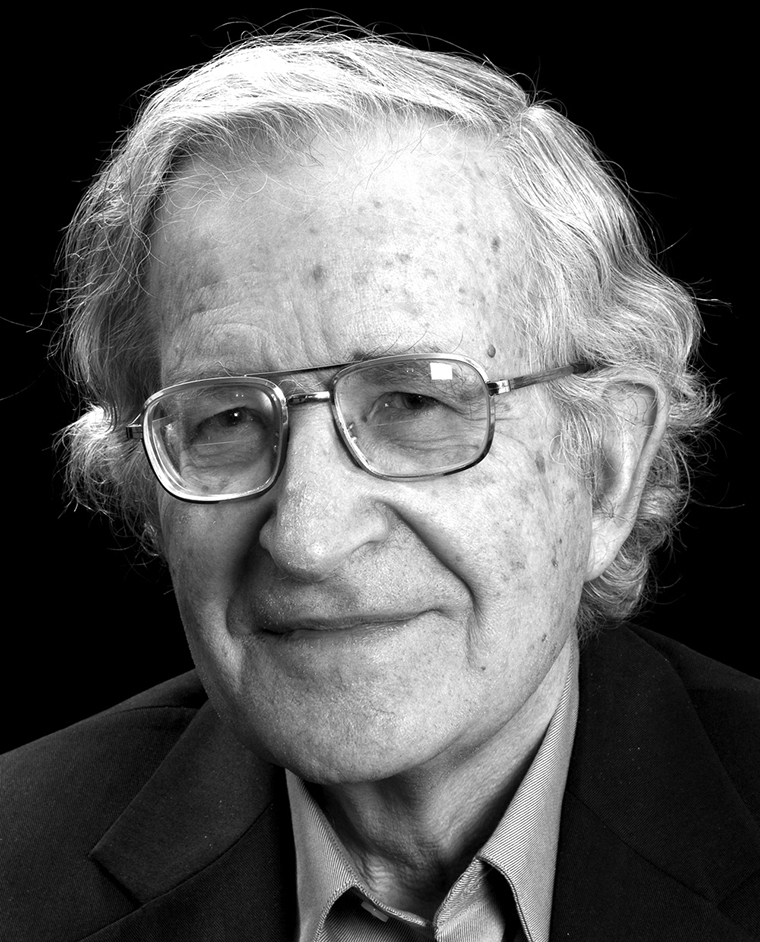

More than thirty years ago I wrote a letter to political activist and social critic Noam Chomsky, and, much to my surprise, he replied. A few years later we did the first of many interviews that aired on my radio program, Alternative Radio. I’ve always been struck by how he peels away the layers of untruths and hypocrisies that support those in power, deconstructing the myths that hide the way repressive institutions work and who benefits from them. Chomsky has long insisted that the dominant forms of authority — governments, corporations, educational systems, the media — must justify themselves or be dismantled. His scathing criticisms of U.S. foreign policy and military interventions have earned him both accolades and death threats.

Chomsky was born in Philadelphia in 1928. His parents, born in Czarist Russia, were both teachers, and his father was a noted Hebrew scholar. Chomsky attended a progressive school that emphasized independent thinking. At the age of ten he published his first article in the school newspaper, about the fall of Barcelona in the Spanish Civil War. (His sympathies lay with the Spanish anarchists.) By the time he was twelve, his parents were letting him take the train to New York City, where he would spend time at his uncle’s newsstand and at anarchist offices and secondhand bookstores around Union Square. In 1945 he entered the University of Pennsylvania, where he would earn a BA, MA, and PhD in linguistics. He joined the faculty of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1955 and has been there ever since. For nearly sixty years he was married to Carol Schatz, who died in 2008. They had three children together.

Someone once said that there are two Noam Chomskys: the pioneering linguistics professor and the political activist. But whether Chomsky is probing the origins of language or assessing ideological manipulations, the common thread throughout his work is his commitment to questioning assumptions. He didn’t set out to become an activist, but the Vietnam War sparked a sense of moral outrage in him. He was involved in movements for tax and draft resistance, protested outside the Pentagon, and was arrested multiple times. In 1967 he wrote an influential article, “The Responsibility of Intellectuals,” criticizing state power and its “academic apologists” and urging scholars to fulfill their public obligation “to expose the lies of governments, to analyze actions according to their causes and motives and often hidden intentions.”

Chomsky has an extraordinary ability to distill and synthesize reams of information, but when I’m asked what he’s like, I find myself talking about his compassion, warmth, and humor. I was with him once in Brazil when he spoke to an audience of thousands. Afterward strangers were calling out his name and thanking him. Their adulation was intense, but it didn’t seem to go to his head. He’s told me many times that he considers it a privilege to do the kind of work he does.

Chomsky constantly reminds us to challenge accepted dogma. He believes that you don’t need an advanced degree to perceive the truths that are often disguised by propaganda and euphemisms like “free trade” and “national interest.” You just need a willingness to consider that one person’s advantage usually arises from another’s disadvantage. When he accepted the Sydney Peace Prize in 2011, he said we should never forget “that our wealth derives in no small measure from the tragedy of others.”

Now eighty-five, Chomsky has retired from active teaching duties at MIT, but he continues to travel and speak around the world. He is the author of Hegemony or Survival, Failed States, the best-selling 9-11, and many other books. My collections of interviews with him include Imperial Ambitions, What We Say Goes, and Power Systems.

For this conversation I joined Chomsky in his office at MIT on February 3, 2014. It was the day after the Super Bowl, a commercial extravaganza in which advertisers paid $4 million for thirty-second spots. Chomsky mentioned that he found it interesting how so much effort went toward trying to get people to pick one unnecessary commodity over another. These “exercises in mass delusion,” he said, are a good reflection of how our society works.

NOAM CHOMSKY

Barsamian: From an early age you were attracted to anarchism. What is it about anarchism that appealed to you?

Chomsky: It seemed to me a sort of truism that illegitimate structures of authority shouldn’t exist. Any structure of authority or hierarchy or domination bears the burden of proof: it has to demonstrate that it’s legitimate. Maybe sometimes it can, but if it can’t, it should be dismantled. That’s the dominant theme of what’s called “anarchism”: to demand that a power structure — whether it’s a patriarchal family or an imperial system or anything in between — justify itself. And when it can’t, which is almost always, we should move to get rid of it in favor of a freer, more cooperative, more participatory system.

Barsamian: One of the anarchist thinkers who influenced you was Rudolf Rocker, who wrote, “Political rights do not originate in parliaments. They are, rather, forced upon parliaments from without.”

Chomsky: From below, in fact. Power systems do not give gifts willingly. You will occasionally in history find a benevolent dictator or a slave owner who decides to free his slaves, but these are a statistical anomaly. Those with power will typically try to sustain and expand their power. That’s true of parliaments, too. It’s only popular activism that compels change.

Barsamian: In an essay from the early 1970s you write about predatory capitalism, “It’s not a fit system. It is incapable of meeting human needs.” If so, then what sustains capitalism?

Chomsky: There are two things. The first is the natural tendency of those with enormous power to secure and maximize their power, as I just said. The second is the passivity or hopelessness or fragmentation of those forces that Rocker was talking about, the people who could make a change if they rose up.

Predatory capitalism has become a threat not just to freedom but to our continued existence. In the early 1970s two close friends of mine — one was the head of earth sciences at Harvard, and the other was the head of meteorology at MIT — both came to me with gloomy reports that were just beginning to leak out, indicating that we might be facing a severe environmental crisis. By now that crisis should be at the forefront of everyone’s consciousness. This predatory capitalist system is driving us over the climate-change cliff. Every new issue of a science journal that I read has more alarming discoveries about the imminence of the threat. It’s not hundreds of years off; it’s decades. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC], which is pretty conservative, says we have maybe fifteen years to do something about it.

Meanwhile predatory capitalism is telling us we have to extract every drop of fossil fuel from the ground by whatever destructive methods we can, even though it will increase the threat. The excuse offered is that this creates jobs, but that’s not the real reason. In modern political discourse the word jobs is a euphemism for an obscene seven-letter word politicians and corporations don’t pronounce: P-R-O-F-I-T-S. They won’t say “profits,” so they tell us it’s because they care so much about working people that we have to keep using fossil fuels at a rate that endangers humanity’s future.

Humanity has been threatened with destruction since the invention of the atom bomb, whose dark shadow still hangs over us. But in that case, at least, we know in principle how to eliminate the threat: disarmament. In the case of the climate, there is no obvious fix, and the longer we wait, the worse it gets. Yet the major sectors of the corporate system — the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, energy corporations, and so on — are carrying out massive propaganda campaigns to try to convince people either that there is no climate change or that it’s not caused by humans; it’s because of sunspots or something. It’s almost surreal.

One aim of the corporate-backed American Legislative Exchange Council [ALEC] is to bring “critical thinking” to public schools — meaning that if a sixth-grade class learns about climate change, we should also teach them climate-change denial, so they will learn to weigh the opinion of 99 percent of scientists on the one hand versus a half dozen skeptics hired by corporations on the other. If aliens from outer space were watching this, they would conclude that humanity is an unviable species, an evolutionary error.

Barsamian: ALEC is largely funded by the billionaire Koch brothers.

Chomsky: Yes. There are, of course, elements in the world that are trying to protect the environment. Overwhelmingly it’s the so-called backward or primitive peoples: the First Nations in Canada, indigenous Latin Americans, aborigines in Australia, the Adivasis in India. Everywhere you look around the globe, the pretechnological societies are trying to keep us from destroying ourselves.

Barsamian: Is our economic system even capable of preserving and protecting the environment?

Chomsky: Our form of capitalism has foundational properties that drive everything toward catastrophe. We don’t have a true market system, because corporations rely heavily on the state, but we have something like one, and in a market system you do not pay attention to “externalities.” If you and I make a transaction, we each try to maximize our own benefit. We don’t ask, “What will be the effect of our transaction on that guy over there?” If I buy a car, for example, I’m increasing pollution, the chance of accidents, and other societal problems, but all I care about is having a convenient way to get around.

Take the investment-banking firm Goldman Sachs. When its employees make a risky transaction, they probably try to reduce the risk to Goldman Sachs, but they don’t pay attention to systemic risk — that is, the possibility that if their transaction goes bad, the whole system will collapse, as happened with the multinational insurance corporation AIG. Goldman Sachs doesn’t have to worry much, because the government is going to bail it out. This means that risk in the financial sector is underpriced, so companies are taking more of it than they should, and that can be devastating. It’s part of the reason for the current financial crisis.

Of course, when it comes to a financial crisis, the taxpayers will be bamboozled into bailing out banks. The environmental crisis is much worse. For the Koch brothers, or even those who aren’t as far on the far-right fringe as they are, the need to make higher profits trumps all else. That’s the nature of the system. If you’re a CEO or a member of a board of directors, you’re supposed to make profits and not pay attention to the costs to others, even if one of those costs may be the end of our species. It’s just an externality and therefore a footnote.

Can we change the system? Sure, because it’s not a law of nature. It’s another of those illegitimate structures of authority I was talking about earlier. It has no right to exist.

Barsamian: Who do you see clamoring for change in this country?

Chomsky: There are protests, but so far not at a scale that can compete with the vast economic resources and political influence of the major energy corporations. That’s why, if you look at the discussion in the newspapers, climate change is presented as a “he says, she says”: maybe it’s happening; maybe it isn’t. You can never be 100 percent certain in the sciences, but this is about as close to a consensus on a complex phenomenon as you will find.

Barsamian: I think the IPCC report you referred to used the figure 95 percent certainty.

Chomsky: The support for the existence of climate change is overwhelming. There are a few critics — the deniers — who get more than their share of publicity. There is also a much more sizable group of critics who are almost never interviewed. They’re the ones who think the IPCC reports are too conservative. Remember, uncertainty means it might be not as bad as we think, or it might be even worse. The corporate media present only the “Maybe it’s not as bad” side, but a large portion of critics are saying, “It’s much worse than you think.” And they’ve been shown to be correct, as more and more studies come out with ominous predictions.

Barsamian: What role does the military-industrial complex play? The Pentagon is often called the number-one polluter in the world.

Chomsky: Not only that, it’s considered the number-one threat to the world. It was barely reported in the U.S., but a WIN/Gallup poll that came out in December 2013 asked people in sixty-five countries, “Which country is the greatest threat to world peace?” The U.S. was number one with three times as many votes as the second-place country, Pakistan. That’s the world’s opinion. Meanwhile the “international community” — which means the U.S. and whoever happens to be on its side — says that the greatest threat to world peace is Iran. The Western press and scholars say that most of the Arab world supports the U.S. on this, but there have been extensive Western polls of the Arab world, and pretty consistently people there identify the U.S. and Israel as the major threats. They don’t like Iran; there is Arab hostility toward Iran that goes back centuries. But they don’t regard it as a threat.

It’s not Arab people but Arab dictators who support the U.S. Our contempt for democracy is so deep-seated that if a country’s dictator supports us and its population opposes us, we say the country supports us. What matters is what powerful, reactionary dictators think.

The U.S. claims to be dedicated to democracy. In fact, we take credit for the alleged upsurge in democracy around the world. There has been much commentary and discussion on how George W. Bush’s foreign policy influenced the Arab Spring. But what do the Arabs think about American attempts to “promote democracy”? A stunning 3 percent believe these efforts made a difference. If you ask people in Iraq, I think it is about 1 percent. But that’s just the opinion of the rabble. It doesn’t count.

The most interesting work on democracy in Latin America is by a man named Thomas Carothers, founder and director of the Carnegie Endowment’s Democracy and Rule of Law program. He’s a good, careful scholar, and also a conservative: he considers himself a neo-Reaganite. He was in President Reagan’s State Department, in fact, working on democracy promotion. When he studied the effect of U.S. foreign policy in Latin America, he called American leaders “schizophrenic”: they talk about promoting democracy, he said, but they consistently work to undermine it.

Carothers says the efforts to promote democracy in Latin America were sincere, but the results were the opposite of what we expected: significant steps toward democracy occurred only in the countries where U.S. influence was limited, like the Southern Cone of South America. In the regions where the U.S. was influential, however, the outcome was much worse. Carothers says the reason is that the U.S. would support only top-down forms of democracy, in which traditional elites friendly to American interests remained in power. So there’s the record: the more influence the U.S. has on a country, the less democracy there is in it.

You see this all over. I’ve been following an online debate among historians about why the U.S. got into Vietnam in the 1950s. There are serious scholars who say, “We had to go in. We were afraid of the Soviet Union.” That’s like saying right now that everybody in the world ought to attack the U.S., because they’re all afraid of us.

U.S. intelligence agencies were instructed in the 1950s to find evidence that North Vietnam was a puppet of the Soviet Union or China or the Sino-Soviet conspiracy. And they worked hard on it. They found that Vietnam seemed to be the only country in the region where there was no Soviet or Chinese influence. But wise guys like Harry Truman’s secretary of state, Dean Acheson, concluded that the apparent absence of influence actually proved its existence: North Vietnamese president Ho Chi Minh was such a dedicated slave to China and the Soviet Union that those countries didn’t even have to give him instructions. That serious historians can look at this theory and not ridicule it is mind-boggling.

Barsamian: This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty, which created Medicare, Medicaid, and food-stamp programs, among other things. Today we have greater income inequality than in the 1960s, yet there’s a widespread push to reduce food stamps and cut unemployment benefits.

Chomsky: The 1960s was a frightening time to elites, and not just conservatives. Liberal elites, too, were scared. Students were speaking up. Women and minorities were demanding more rights. The rabble weren’t being passive and obedient the way they were supposed to be. They were trying to enter the political arena and make demands.

Reactions from both ends of the political spectrum were interesting. On the Right there was future Supreme Court justice Lewis Powell’s confidential memorandum to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, describing capitalists as an embattled minority who were being attacked by the leftists and Marxists who had taken over the media, the universities, and the government. But, he said, capitalists had all the money and could beat back this Marxist onslaught.

These people who own everything are extremely paranoid, like a pampered child who feels as if the world is coming to an end if he loses one toy. That’s the tone of the Powell Memorandum.

At the other end you had the so-called liberal internationalists of the Trilateral Commission. These were the people who staffed President Carter’s administration. They weren’t what you and I would call “liberal.” In 1975 the commission issued a report saying, in effect, that there was too much democracy in the world. It said that in the 1960s, “special interests” like women and youth and old people and farmers and workers had all tried to enter the political arena, putting too much pressure on the state. So there had to be more moderation in democracy. Citizens expected too much. But there was one sector the report didn’t mention: the corporate sector. Apparently corporations were not a special interest in the eyes of the commission, so we didn’t have to worry about them.

The report also said that universities and schools were failing in their duty to indoctrinate the young. That’s why we had young people on the streets protesting the war and calling for women’s rights and so on: they hadn’t been indoctrinated properly. So the state needed to intervene. The commission said the media, too, were getting out of hand; they were too antagonistic, too adversarial. So maybe there should be more state control of the media. These are the “liberals” I’m talking about.

And there were changes in the economy taking place in the mid-seventies. That was the beginning of the enormous growth of financial institutions.

Barsamian: And about that same time, wages went flat for working people.

Chomsky: The two are connected: the stagnation or decline in wages and the rapid increase in profits. The more concentrated economic power gets, the more it controls legislation, which drives the vicious cycle until you get to the mess the country is in now.

The War on Poverty did cut poverty notably. But beginning in the 1980s that trend reversed. Incidentally that’s not just in the U.S. That’s around the world. It’s even more extreme in Europe right now than it is here. European countries are imposing austerity during a recession, which even the International Monetary Fund says is economically unfeasible. The effect is the dismantling of the welfare state, Europe’s great achievement in the postwar period. The business world talks almost openly of this as a goal.

What do the Arabs think about American attempts to “promote democracy”? A stunning 3 percent believe these efforts made a difference. If you ask people in Iraq, I think it is about 1 percent.

Barsamian: And in the U.S. we’re seeing those attacks on food stamps and unemployment benefits.

Chomsky: Not just that. There are attacks on Social Security and public schools, too. Anything that might benefit the general population has to be cut, because the goal of society must be to further enrich and empower the rich and powerful. This is the obvious plan of people like Paul Ryan and other Republicans, but the Democrats are not so different. It used to be said fifty years ago that the U.S. was a one-party state — the Business Party, which had two factions, the Democrats and the Republicans. That’s not quite true anymore. We’re still a one-party state, but there’s only one faction. Both parties have drifted so far to the right that what we call “Democrats” are really moderate Republicans. The “Republicans” are off the chart.

Getting back to the changes in the economy: One, as I mentioned, was the explosion of the financial sector. By 2007, right before the latest crash, about 40 percent of corporate profits were being made by financial institutions, which do nothing for the economy. They’re probably even harmful to the economy.

Another big change was when manufacturing shifted overseas in search of cheap labor, easily exploitable workers, zero regulation, and so on. The so-called free-trade agreements accelerated this process. So we have shifted the productive part of the economy abroad — the profits are still here, but the work is done there — and encouraged the growth of predatory, parasitic financial institutions.

Martin Wolf, an economist at the Financial Times and probably the most respected financial correspondent in the Anglo-American world, describes the banking sector as being like a larva that eats away at its host, the market system. Recently Jamie Dimon, the CEO of JPMorgan Chase, had his salary almost doubled because he ensured that the bank had to pay only $13 billion in fines — a pittance to them — for its criminal activities and no one got sent to jail. That’s what’s going on all the time.

The attacks on food stamps and Social Security and schools are part of a broader attempt to undermine the heretical, subversive notion that you ought to care about other people. The powerful want to get rid of that. You shouldn’t care about anyone else, they say. You should just care about yourself or the masters you serve. This view is called “libertarian” in the U.S., but it’s the most extreme anti-libertarian force that has ever existed. Its attitude is: Why should I pay for anything that I don’t directly benefit from? Why should I pay taxes for schools? I don’t have kids in school. Why should I pay for the kid across the street to get an education? Why should there even be public schools? Why should there be roads? Why should there be Social Security? Why should there be food stamps? Those moochers should get out and work, like I do, even though I’m making all my money off the taxpayers via the financial system.

Modern libertarians are exactly the opposite of their heroes Adam Smith and David Hume, the founders of classical liberalism, who took it for granted that the fundamental human drive was compassion and mutual support.

Inequality in the U.S. is the result of a global “free-trade” movement that has led to similar outcomes virtually everywhere. China, for example, has higher income inequality than the U.S. It’s the natural consequence of policies designed to benefit narrow sectors of the population.

In parts of Latin America that have freed themselves from U.S. domination, there’s been significant poverty reduction in the past decade. But not in Mexico, which is considered the most privileged country in the region. In fact, poverty has gone up there. Mexico is under the umbrella of the North American Free Trade Agreement. It’s like what I said before about democracy: the farther a country is from an alliance with the U.S., the less poverty it has.

Barsamian: Former U.S. Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis once said, “We can either have democracy in this country, or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.”

Chomsky: That’s clearly true. It’s been strikingly demonstrated by mainstream academic political science, which studies the relationship between public attitudes and policy. Researchers find in their polls that the attitudes of the poorest 70 percent of Americans have essentially no effect on policy. Those people are disenfranchised. It doesn’t matter what they think. Political leaders just don’t pay any attention to them. As you move up the income scale, you see a little more influence. By the time you get to the top, attitudes and public policy are very similar, because the few at the top are the ones who design the policy. They essentially get what they want. You can’t call that democracy. It’s some kind of plutocracy. Columnist Jim Hightower has a good term for it; he calls it “radical kleptocracy.” But whatever it is, it’s certainly nothing like democracy.

The problem has been exacerbated further by the private financing of elections, which has gotten out of control. Not only elections are being bought, but also committee positions in Congress. It used to be that a Congressional representative would get a committee chair because of seniority or service. Now it’s a result of how much money the representative brings into the party coffers. There is talk about the huge expenditures for presidential elections, but House elections are in many ways more dominated by spending. Thomas Ferguson, the political scientist who has done the most work on this, came out with a careful study of funding for House elections in the 2012 campaign, and it’s almost a straight line: the better you’re funded, the better your chances of being elected — which essentially means the elections are being bought.

Barsamian: Let’s move on. You once said that Amos was your favorite biblical prophet. What is it about Amos that attracts you?

Chomsky: What attracted me to him from childhood is that he claimed not to be a prophet, but only a simple shepherd and farmer. And then he went on to speak against social and economic injustice, saying that behaving justly was more important than ritual. The word prophet, by the way, doesn’t have anything to do with prophecy.

Barsamian: Does it come from the Hebrew word navi?

Chomsky: Yes, navi. Nobody knows exactly what it means. It’s translated as prophet, but it’s a dubious translation. The navi didn’t prophesy. They did political analysis; they condemned evil kings and power structures; they called on people to care for the oppressed and widows and orphans. They were what we would call “dissident intellectuals.” And for this they were driven into the desert, imprisoned, and condemned.

Another of my favorite prophets was Elijah. He’s the original “self-hating Jew.” He was called before Israel’s King Ahab, who is the epitome of evil in the Bible, and asked, “Why are you a hater of Israel?” which meant he had condemned the king. If you are deeply totalitarian, you identify the society with its rulers. So people who condemn the rulers are against the society: they’re anti-American or anti-Soviet or anti-Israel.

The U.S. is about the only nondictatorship where this is common. You’re anti-American if you criticize U.S. rulers. In Italy you aren’t called anti-Italian if you criticize the Italian president.

There’s an extraordinary display of patriotism in the U.S. In other democracies people don’t have flags all over or venerate their rulers. Take George Washington, for example. He was regarded as a unique, almost superhuman being. All kinds of stories were invented about him, like his chopping down the cherry tree. There was a statue made around 1820 of Washington as a Roman general. It’s still in the capitol building of North Carolina. There was some criticism of it — that one of his shoulders was bare, which was considered not dignified enough — but the idea was clearly that you should venerate this person, who was not a particularly admirable president. The Iroquois called him “Town Destroyer,” because he went on a campaign to, in his words, “extirpate” them. And of course he was a crooked land speculator. But he is the father of the country, so we have to venerate him.

It continues right up to Ronald Reagan. The state ceremony after Reagan died was like something straight out of Pyongyang, North Korea. Here is this miserable thug, this racist killer, but after his death people began a campaign to venerate him. Now you can’t go anywhere in the U.S. without finding a Reagan airport or a Reagan government building. It’s the same with John F. Kennedy for the liberals. This venerating of heroes is on par with ostentatious demonstrations of patriotism, like flags on bridges. I don’t think you see this anywhere else in the world. I certainly haven’t. I know foreigners who are astonished by it when they come here.

Barsamian: The term “self-hating Jew” has been applied to you on occasion.

Chomsky: I’m happy to be associated with Elijah, who opposed the most evil king in the Bible.

Barsamian: In 1953 you and your wife, Carol, lived in Israel on a kibbutz — a kind of communal farm. You also considered staying in the country for a while. What changed your mind?

Chomsky: We were in a very left-wing kibbutz. We were there for a couple of months. It was summer, and we were both students. Yes, we thought about living there. Carol went back once by herself. But we just decided not to.

Barsamian: You’ve told me you encountered traces of racism during your stay there.

Chomsky: Pretty strong ones, yes. To give you an example: There was a group of young Moroccan Jews, who I later discovered had been pretty much kidnapped from their parents. They were there to be educated in the proper Israeli style of Judaism. We lived among them, but we were warned by the kibbutz leaders to lock our door, because the Moroccan kids were a bunch of criminals. This wasn’t true. They were perfectly nice kids.

I had a friend on the kibbutz who was the editor of the Arab newspaper. He’d also go around to Arab villages to try to drum up votes for the liberal party, and I sometimes went with him. At that time I understood enough Arabic to be able to follow conversations. He would ask the villagers what he could do for them in exchange for their votes. Some villagers lived across the road from a kibbutz they wanted to trade with, but Arabs weren’t allowed to cross the road unless they first went to Haifa, twenty miles away, and got a permit.

Some kibbutz members didn’t object to this treatment of Arabs, but others did. I had friends who served guard duty at night, watching out for people they called “infiltrators.” Many of my friends wouldn’t carry arms when they went to the guard tower, because the so-called infiltrators were just the people who used to live on that land and were coming back to try to harvest their own fields. My friends weren’t going to shoot at them.

I was working in the fields one day with an older member of the kibbutz when I noticed a large pile of stones and asked him what it was. He didn’t say anything, but later he took me aside and said it was the remains of a friendly Arab village they had destroyed in 1948 during the Arab-Israeli War. He felt guilty, he said, but the Arab tanks had been just a couple of miles away, and they hadn’t known what was going to happen and didn’t want to take chances.

That’s one of many villages whose destruction went unrecorded. And there were hundreds destroyed that were recorded.

Barsamian: Palestinian villages.

Chomsky: Yes.

These people who own everything are extremely paranoid, like a pampered child who feels as if the world is coming to an end if he loses one toy.

Barsamian: In an interview we did in late June 2013, you said, “The Israeli Left is almost nonexistent.” In the U.S. there was a perception for years that Israel had a vibrant Left. What has happened there?

Chomsky: There was a vibrant Left. It’s seriously declined. A few left-wing people remain — good, honorable, courageous people — but they are scattering. One of the best, journalist Amira Hass, lives in Ramallah, because she doesn’t want to live in Israel anymore. Quite a few close friends of mine who were committed to Israel have left. They’d been born there and had wanted to stay, but they couldn’t stand it anymore. The country has moved so far to the right.

What’s happening in Israel is similar to what happened in South Africa under apartheid [a system of racial segregation in place there from 1948 to 1994]. You can read the history of South Africa and replace “South Africa” with “Israel,” and it almost works.

We know now from declassified U.S. documents that around 1960 the South African foreign minister told the American ambassador that, despite worldwide condemnation of apartheid, he knew he could count on the U.S. to vote in South Africa’s favor in the United Nations. The gist of the message was “As long as you support us, it doesn’t matter what the rest of the world thinks.”

As early as the 1960s there was an anti-apartheid movement in England. By the 1970s the UN was beginning to condemn apartheid. The South African government was also carrying out murders and aggression in Angola; it was illegally occupying Namibia; it was committing atrocities in Mozambique — in essence trying to intimidate its black African neighbors and impose its own rule across southern Africa. The reason South Africa didn’t get away with this isn’t talked about much in the U.S. It was because of Cuba. If you remember, when Nelson Mandela [a leader of the anti-apartheid African National Congress (ANC) Party] was released from prison, he immediately thanked Fidel Castro and the Cubans for being an inspiration to him and for their enormous role in liberating Africa and ending apartheid. The Cubans drove the South Africans out of Angola and Namibia. The Cubans fought alongside black African soldiers to defeat the South African Army. Mandela said this had an important psychological effect, because it put to rest the image of the invincible white man.

Meanwhile the U.S. was supporting the apartheid regime. Reagan, in particular, refused to believe that there was a race problem in South Africa. His view was that it was just tribal warfare. He and British prime minister Margaret Thatcher were supporters of apartheid right to the end, though she was less of a fanatic than he was. They both supported terrorist groups in Angola, even after the South African Army had pulled out. When the U.S. Congress passed sanctions against South Africa, Reagan vetoed them. And when Congress overrode his veto, he violated the sanctions. The ANC was condemned by the U.S. as a terrorist group. In fact, Mandela himself was on the terrorist watch list until 2008.

My point is that something similar has been going on in Israel. In 1971 the Israelis were offered a full peace treaty by Egyptian president Anwar Sadat if they would pull out of the Egyptian Sinai Peninsula. They rejected it. The Israelis had big plans at the time to settle and develop the Sinai, to drive out the Bedouin population and build all-Jewish cities and kibbutzim. Israel chose expansion over the security of a peace treaty with Egypt, which has the largest military force in the Arab world. That was a fateful decision.

The more you pursue expansion and reject diplomacy, the more isolated you’re going to become. And friendship with the U.S. is the last resort for isolated regimes. Israel is taking the same position that South Africa did: the rest of the world can be against them as long as the U.S. supports them.

Israeli policies of expansion have brought sanctions against Israel like the ones against South Africa in the past. Europeans are beginning to boycott anything associated with the illegal settlements on the West Bank. One of the major Danish banks just canceled its dealings with Israel’s Bank Hapoalim, because of its activities in the settlements. The European Union has passed resolutions — I don’t know if it’s going to implement them — refusing contact with any Israeli research institutions that are involved with the settlements.

Barsamian: In the U.S., Code Pink is leading a boycott against Israeli products made in the West Bank.

Chomsky: And Israel’s response is to say that the sanctions and boycotts are anti-Semitic. They believe Israel is being unfairly singled out. It’s the same as what supporters of apartheid said: “Why condemn apartheid? Look how awful China is.” The old Soviet Union used to say, “Why are you condemning what we do in Czechoslovakia? What the Americans do in Central America is much worse.” It’s the standard defense of those who support or commit atrocities.

There’s a perfectly obvious reason for the U.S. to scrutinize Israel. Yes, there are terrible things going on in other places, but in Israel we’re helping carry them out.

Barsamian: In what way?

Chomsky: First of all, there’s the $3 billion in annual U.S. aid, which is probably twice that when you figure in all the indirect aid. Then there’s the diplomatic support and the vetoes in the UN Security Council to protect them, just as Reagan vetoed Security Council resolutions condemning South Africa. Finally we have very close, intimate military relations with Israel, much more so than we did with South Africa. We’re Israel’s main ally. The Israelis can get away with what they’re doing only because the U.S. supports it.

South Africa, too, could not have continued its apartheid policies without strong U.S. support. Even Jimmy Carter, who was actually opposed to apartheid, assisted the terrorist forces in Angola and tried to drive the Cubans out. It wasn’t a pretty picture. Reagan was much worse, of course. But the U.S. had a special reason for not condemning apartheid — namely our involvement in it.

Outside of the U.S. there’s almost no country that supports Israeli crimes. The New York Times will say that “some countries” regard the settlements as illegal. No, not some countries. The whole world except for the U.S. regards them as illegal. So do the UN Security Council and the International Court of Justice. Even the U.S. regarded the settlements as illegal until Reagan entered office. Under Reagan they were referred to as “an obstacle to peace.” Under Obama they are called “not helpful for peace.” That’s it.

Barsamian: Do you support the global Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions [BDS] movement, which is pressuring Israel to end the occupation of the West Bank?

Chomsky: I think such tactics can be effective. There were boycotts, divestments, and sanctions used against apartheid. There was no movement behind them, but the tactics were the same, and by and large they were pretty successful. Academic institutions were targeted for racist hiring practices. Sports teams that would not allow blacks were targeted. Products were boycotted if their manufacture involved the apartheid programs. There were condemnations of the treatment of black workers. The United Nations banned weapons shipments to South Africa.

The BDS movement, however, does not distinguish between principled, effective actions and the kind of feel-good activities that are ineffective and even harmful. For example, boycotting products from the settlements or research activities conducted within the settlements makes sense. It’s intelligible, it exposes the issues, and it strikes at the crucial point: the illegal occupation. But when the BDS movement talks about boycotting Israeli universities for being “parties to state policies,” it’s meaningless. Why don’t we boycott Harvard because of the number of blacks in U.S. prisons? Because it’s an empty, counterproductive gesture, and the predictable reaction is a huge backlash.

When you’re an activist, you have to think about the people you’re trying to protect. Not every action that makes you feel good is going to be helpful to them. Some might be harmful. It’s like in the late 1960s when some young Americans were so outraged and desperate over the Vietnam War that they decided to protest by walking down streets and breaking windows. The Vietnamese antiwar activists were strongly opposed to that. If you break windows, they said, you’re only going to create a backlash in support of the war.

The Vietnamese activists advocated tactics so mild that the American antiwar movement laughed at them. I remember meetings where the Vietnamese talked about how impressed they’d been when a group of American women had stood at the graves of U.S. soldiers and mourned. It was pretty hard to sell a protest like that to the American activists, but the Vietnamese didn’t care whether the activists felt good. They wanted the war to end.

The first slaves were already here in North America in 1620. That’s how long racism has been a problem. And we still haven’t dealt with it. The plight of the black population in the U.S. is the residue of centuries of slavery and racism and white supremacy.

Barsamian: So if Israeli policies continue on the current trajectory, what do you see in that country’s future?

Chomsky: Almost uniformly, Israeli, Palestinian, and American commentators pose the issue as if there were only two possible outcomes: either the two-state option that the entire world has been supporting for thirty-five years and that the U.S. has been blocking, or else Israel takes over the whole region — all of the West Bank, all of the former Palestine. If that happens, Israel will have a demographic problem: too many Palestinians within a Jewish state. Then there will be a civil-rights struggle, an anti-apartheid struggle. It’s not even an option.

More important, the U.S. and Israel would never accept a one-state solution because they are currently pursuing a third option: Israel takes over everything within what’s called the “separation wall.” It’s actually an annexation wall that breaks up the West Bank into pieces. Israel is slowly seizing about a third of the West Bank and imprisoning whatever is left between the regions it’s effectively taking over. The Israelis are not taking over the areas where the Palestinian population is concentrated, however, because they don’t want the Palestinians. In fact, one striking difference between Israel and South Africa is that in South Africa the whites needed the black population to serve as their workforce. Israel just wants the Palestinians out, the way the U.S. did the Native Americans. Only these days you can’t just exterminate a whole group, as was done here. So Israel will drive them out. It will annex the territory it wants in the West Bank — the arable land, the water supplies, anything valuable — and leave the Palestinian population to rot outside those areas.

In the 1990s Israeli industrialists advised their government to move from a colonial policy to a “neocolonial policy,” which is what you now see all over the world in post-imperial states. A neocolonial policy maintains the basic structures of imperial domination while giving native elites a gift of some sort to keep them quiet. If you go to the poorest Central African country, there’s at least one place in it where people live in luxury. Or take India, where in the midst of horrible poverty a few live in huge skyscrapers with swimming pools on the fiftieth floor. That’s what Israel is creating in the remnants of Palestine. Ramallah is a modern city: restaurants, stores, theaters. You can go there and think you’re in London. But the rest of the West Bank is disintegrating. Israel is hoping that the Palestinians will just leave. Some peasants might stay on their land and survive somehow, but most will go. The process will continue as long as the U.S. supports it. Once the U.S. doesn’t support it any longer, it will change.

Barsamian: An Alternative Radio listener sent me this quote from historian Howard Zinn: “Small acts when multiplied by millions of people can transform the world.”

Chomsky: Yes, that was one of the main themes of his book A People’s History of the United States and everything else he did. There’s a lot of truth to that. In 1960 four black college students sat in at a segregated lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina. They were, of course, refused service. But the next day more black students came. Pretty soon you had the Freedom Riders, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and massive civil-rights rallies. It didn’t end racism, but it achieved a lot.

The first slaves were already here in North America in 1620. That’s how long racism has been a problem. And we still haven’t dealt with it. The plight of the black population in the U.S. is the residue of centuries of slavery and racism and white supremacy. Historian George Fredrickson has done a comparative study of racism in various countries, including the U.S. and South Africa. He concludes that the U.S. is unique in the extremism of its white supremacy. For example, we talk about Barack Obama as the first black U.S. president. In the rest of this hemisphere he wouldn’t be called “black.” He would be called “mixed race.” But in the U.S. there is still this racist concept that anyone with one drop of African blood is black. It’s so deeply rooted, it’s not even questioned.

The so-called War on Drugs is really a race war. It’s been that way since Reagan. Constraints placed on former prisoners are remarkably similar to the Jim Crow laws in the post-Reconstruction South. That’s why Michelle Alexander titled her book about it The New Jim Crow. After Reconstruction the North granted the South the right to criminalize black life. A black male could be sent to prison just for being a vagrant. Soon a large portion of the black male population was in jail, where it became a slave labor force. In fact, this was a better arrangement for capitalist owners than slavery had been. A slave had been a capital investment the owner had to protect financially, but a prisoner is taken care of by the state. A large part of the American industrial revolution was accomplished with prison labor. Everyone’s familiar with the chain gangs, but you rarely see the images of prisoners working in the mines or the U.S. Steel mills. That went on right through the Second World War, when the military industry needed free labor.

Barsamian: There has been an increase in sectarian violence in countries like Syria, Iraq, and Pakistan, where there have been historical tensions within Islam. Even beyond those Islamic countries — for example, in Myanmar, a largely Buddhist country — Muslims are being killed. In India there was a recent massacre of Muslims in Muzaffarnagar. There are the ongoing issues in Kashmir. Why is this happening now?

Chomsky: What’s happening in Myanmar with the Buddhist atrocities against the Muslim population is different from what’s happening in Syria. In Myanmar it’s essentially ethnic nationalism. These Muslims are mostly immigrants from Bangladesh, and they’re being treated brutally by the Buddhist majority.

In Iraq and Syria the sectarian violence is a side effect of the U.S. invasion of Iraq. There are Shiite-Sunni conflicts in the region that go back centuries, but until the invasion they were muted. In Iraq, for example, there was intermarriage between Shiites and Sunnis. They lived in the same villages and even attended the same mosques. There were differences, but Iraqi nationalism trumped them. Then came the American invasion. In the first couple of years of occupation, Iraqis were saying there wouldn’t be any sectarian conflict because Shiites and Sunnis were too intermingled. But by 2005 it was getting out of hand, and now it’s become vicious and has spread to Syria and all over the Muslim world. The tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran are in part a Shiite-Sunni conflict. I wouldn’t say that’s the only factor, but it’s a major one. When you hit a fragile society with a sledgehammer, a lot of things break.

We should also remember that there is a war going on around the world between the center and the periphery. In the center is the state. On the periphery are tribal societies. Until recently, native tribes were mostly left alone. Take Pakistan, for example: The British tried to conquer the tribal regions there but couldn’t, so they left them largely autonomous and self-governing. When British imperialism ended, the Pakistani government maintained that policy. Then, as part of the so-called War on Terror, the U.S. pressured Pakistan to attack those tribal societies, which created the Pakistani Taliban. Now there’s a global war against tribal Islam. So of course the tribes are striking back. When they do, we call it “terrorism.”

Barsamian: How can people begin to see through the received wisdom about international and domestic affairs?

Chomsky: The main requirements are an open, critical mind and a willingness to question dogma and repressive institutions. Once you’ve got those, you can start reading the news and asking: Is the U.S. really dedicated to democracy? Is Iran really the greatest threat to world peace? Can this economy be sustained? Most of all you have to ask, Is it true? A pretty good criterion is that if some doctrine is widely accepted without question, it’s probably false.

Then you have to join forces with others. There’s not a lot you can do by yourself. Going back to Zinn’s comment, small groups can carry out actions that can light a spark and multiply and lead to other protests, without limit.

Barsamian: Whenever the system comes under any kind of pressure from the people, it offers up what are called “reforms.” Years ago you told me, “When you hear the word reform, you should reach for your wallet, because someone is probably trying to steal it.”

Chomsky: Reform is like most political terms: you have to distinguish between its dictionary meaning and its meaning in political circles, where it usually means “a change approved of by those in power.” Changes they don’t approve of are not called “reforms.” In the February issue of the journal Current History, you can read praise of Mexico’s energy “reform” — namely its opening of its oil resources to international exploitation instead of maintaining those supplies for Mexico. “Educational reforms” in the U.S. refers to various measures that undermine public education.

On the other hand, we shouldn’t reject the idea of reform itself. Public pressure sometimes does impose changes on systems that are true reforms — and not just under liberal administrations. The Environmental Protection Agency, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, and the earned-income tax credit were all created during Nixon’s presidency — not because he was a nice guy, but because he came under outside pressure. These advancements didn’t change the institutional structures; they weren’t revolutionary; but they made people’s lives better.

Barsamian: Folksinger Pete Seeger recently passed away. How much were his protest anthems a soundtrack to your life? Did you play his records at home?

Chomsky: Personally I didn’t, but when my kids were growing up in the 1960s, they did. Music can be very important. One of the most moving experiences I’ve had was being in a black church in the South during a time of horrible racial violence, and people would gather at the church in the evenings and sing gospel, blues, and protest songs together.

Barsamian: One of Seeger’s favorite songs was “Which Side Are You On?” There’s never been any doubt which side you’re on.

Chomsky: Or Pete. He was a very noble character. He went through a lot of persecution.

Barsamian: You’re eighty-five now. Is it different than being eighty-four?

Chomsky: I was told by a cardiologist many years ago that eighty-five is when old age sets in. That’s when you’ve got to start being careful.

Barsamian: Please, be careful.