I first encountered the work of Reverend Lynice Pinkard when I read her essay “Revolutionary Suicide” in the magazine Tikkun. Her writing combined fervor and thoroughness with a big heart. Although she is a Christian — she grew up in the African American church — her analysis of the Hebrew prophets resonated with my Jewish background. When I contacted Pinkard about the possibility of interviewing her for The Sun, she suggested I first listen to some recordings of her sermons, archived on the website of First Congregational Church of Oakland (firstoakland.org), where she served for eight years as a pastor. I did and was impressed by the passion of her presentation and the rigor of her arguments as she exhorted her congregation to switch from a typical American life of consumerism to one of giving without the expectation of reward.

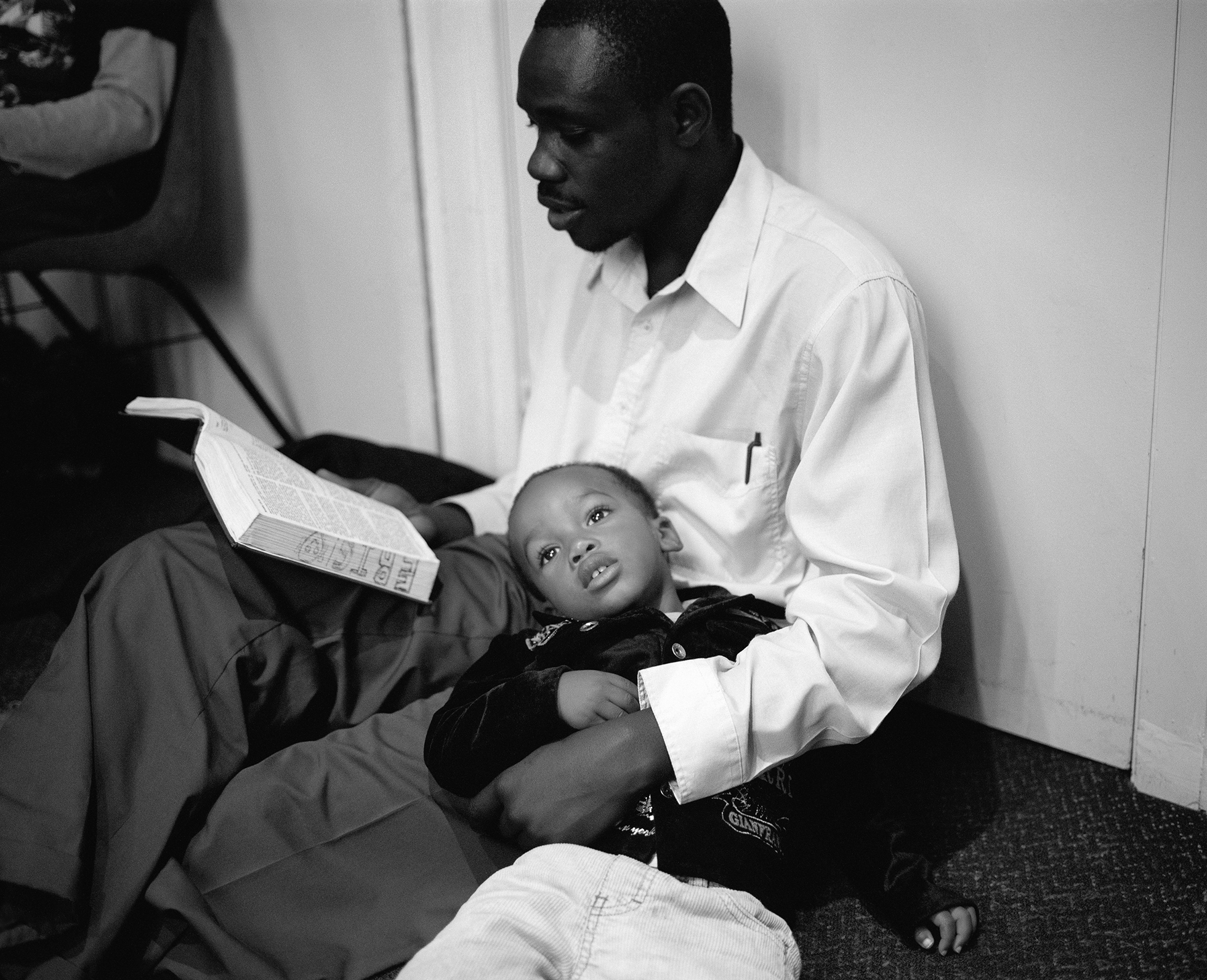

Pinkard’s maternal grandmother was a white German American who married a black evangelist minister in the 1930s, a time when interracial marriage was still illegal in many states. The couple’s biracial children performed at revivals as the Miracle Singing Children of the Gospel, and Pinkard’s mother grew up to marry an African Methodist Episcopal pastor. Pinkard was born in California in 1963, at the height of the civil-rights movement, and she was raised mostly in Kansas City and St. Louis, Missouri. “I’d play with my father’s robes as a girl,” Pinkard says, “try them on, pretend I was preaching.” She attended predominantly black inner-city schools, where she was bullied for having light skin and a white-looking mother. When the bullying got to be too much, her mother had her bused to a mostly white suburban school, where Pinkard first encountered what she calls “white ubiquity”: the belief that what matters to white people is all that matters, and that white people are the standard everyone else should live up to. Pinkard, however, quickly learned the truth of what her African American elders said: “Ain’t nothin’ white about being smart.”

In high school Pinkard came out as a lesbian, and she left the church she’d grown up in, but she never abandoned her faith. She attended Hampton University, a historically black college in Virginia, and after graduation was accepted to law school at the University of California at Berkeley, but she dropped out because she felt called to the work of ministry. She obtained three master’s degrees: two from the Pacific School of Religion in Berkeley and one in counseling psychology from California State University, Hayward.

Pinkard joined the socially progressive United Church of Christ denomination, and in 2002 she became a pastor of First Congregational Church of Oakland, where, at that time, there were only two other people of color in the congregation. She eventually rose to become the senior pastor and, in concert with the congregation, moved the church toward what she calls “dissident discipleship” and “feral Christianity.” She was committed to strengthening the church’s social-justice ministries, but she struggled with what she saw as her conflicting roles — prophetic public witness on the one hand, and builder and preserver of the institution on the other. She wanted to decentralize the church’s hierarchical leadership and put resources into helping the surrounding communities. She resigned from her position as senior pastor in 2010 and currently serves as a volunteer and board member of the food-aid organization Share First Oakland (sharefirst.org) and the community-training institute Seminary of the Street (seminaryofthestreet.org). She also works as a hospital chaplain in the East Bay.

This past spring Pinkard and I met for an interview on the garden patio of an Oakland coffee shop. For nearly four hours we sipped iced tea and grappled with issues of class, race, gender, religion, and politics.

REVEREND LYNICE PINKARD

Leviton: You grew up in the church with a father who was a pastor. How did you respond as a child to the message of Christianity?

Pinkard: I loved Bible stories and the illustrations of Jesus talking to children and holding lambs. He was just a sweet, kind, loving, nurturing friend. Along with my children’s Bible, I would eventually learn to read my dad’s “Interpreter’s Bible,” with all its critical notes and commentaries.

My initial sense of religion was conformist. I thought Jesus was trying to make us all nice, gracious, and agreeable. That began to change when I came to understand my father’s involvement in the civil-rights movement and my mother’s love of justice and her work in our community. My father was part of various coalitions and committees across the country that did grassroots work, and he carried out the vision of Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph Abernathy, and Jesse Jackson, both as a part of the national movement and locally in his ministry.

I also began to understand how living in a low-income community sucks the life out of people, many of whom have no access to opportunities and whose kids attend poorly equipped schools. Because my father was pastor of a church, we were insulated in ways that other people in our community were not. We didn’t have any money, but we had light, heat, and food at the parsonage. Now, I didn’t go to the dentist until I was out of college, and we went to the doctor only if we broke a limb, but we survived.

The civil-rights movement was a middle-class church movement. The goal was to assimilate, to be upwardly mobile, and to show that you deserved to have what white people had and could do what white people did. Religion played a part in that by making black people respectable. Today I do not subscribe to the notion that we should strive to fit into the dominant culture, but many black civil-rights activists in the sixties saw whiteness — and, thus, white people — as the norm, and they wanted the same status that white people had, and that meant acquiring the same symbols of status.

Leviton: Did you have any inkling when you were a girl that you wanted to pursue ministry as a vocation?

Pinkard: I identified deeply with my father’s ministry, and I wanted to emulate him. My siblings and I used to play church. I’d stand on the hearth with a white towel around my neck like a clerical collar and preach. They hated it, but I was the eldest, so they had to go along. As much as I loved Sunday worship services, the cadences of black preaching, the way people expressed their faith openly, the call and response, I also cherished the community, the deep love I felt from the congregation. And Jesus is just about the only man I’ve ever been in love with!

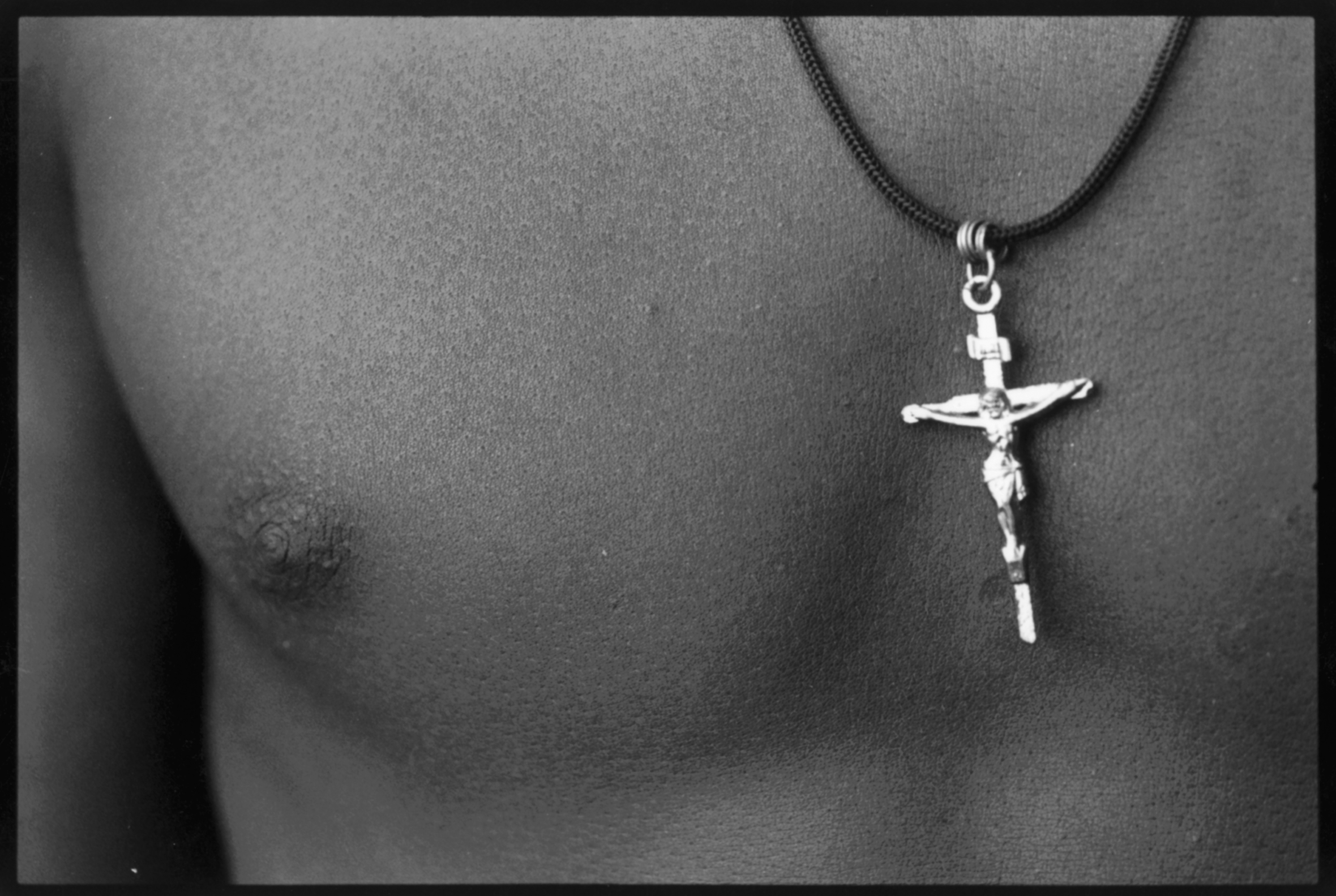

In early high school, though, a kind of fierceness began to develop in me. I sensed that other people thought I was strange because I liked girls. I never felt strange or as if God or Jesus didn’t love me, but I heard in various churches where I sang in community choirs that homosexuals were “a stink in God’s nostrils,” that God was sickened by the sight of us. In my late teens and early twenties I started reading the Gospels more and thinking about them in ways that others around me didn’t. In my early thirties I came to understand that, for me, the cross was not a religious symbol; it was a symbol of dissidence. I realized that people who love fiercely often die violently: Gandhi, Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King Jr. The Jesus I was hearing about in many churches and the Jesus I was reading about in the Gospels seemed like two different people. Jesus became more of a revolutionary in my eyes. He is what the glory of God looks like on planet Earth. By meeting us in Jesus Christ, God “touched down” and became vulnerable to suffering, even to the point of violent death, to be in solidarity with us and to bring about justice, which I like to think of as love in action. The best of our leaders in the U.S. and around the world also touch down in solidarity with suffering people and a suffering planet.

Leviton: You attended UC Berkeley’s law school but left without a degree. What were you hoping to achieve by becoming a lawyer, and why did you quit the program?

Pinkard: I was twenty-four when I started law school, and I’m sure that I wanted to become a lawyer to please my father and to make money. I also think I wanted to “be somebody,” to assimilate and get respect through status, as I’d been raised to do; to become better off than my parents and grandparents; to be a credit to my family and my race. But then I began to realize that I didn’t like what I saw when I looked up the social ladder. The people and situations that I most resonated with were lower down, firmly planted on the ground of being, in the circumstances of everyday life. From what I could see, I didn’t want the “prosperity” they had at the top. I came to feel as if I were in line for a face slap and was complaining about the wait. During my breaks between classes, I would go to my car and pray for all of us to be set free — rich and poor, people of color and white folks alike — from the forces that were oppressing us.

I had realized that everyone in this culture is eating from the same imperial cookie. Maybe the sprinkles on your cookie are blue and mine are green, but our cookies have the same empty or even deadly ingredients. I understood, probably for the first time, that the Gospel has nothing to do with becoming successful or wealthy or respectable or comfortable — or with self-preservation of any kind. The Gospel is basically about a scandalous love affair between God and people who need freedom but often don’t know it. When I discovered this, I lost whatever interest I’d had in working to gain status and “sophistication.” Still, I struggled with what to do next. How many young black women from impoverished backgrounds got to graduate from UC Berkeley’s Boalt Hall? Did I owe it to my parents and grandparents to finish? One night I fell asleep on the couch at my sister’s house, and in a kind of waking dream I heard somebody or something say to me, “You’re not a lawyer. You’re a preacher.” I woke up crying and quit law school soon after that.

I did get other master’s degrees, because I wanted to be able to make a living, but I was mainly committed to following my calling to serve others. I got ordained in the United Church of Christ because I fell in love with the people of First Congregational Church of Oakland and wanted to be their pastor. I also did it because I believe in the potential of churches to provide needed structures of accountability and support and to bring to bear our enormous collective resources for love and justice in the world. In the end, though, I narrowly escaped bondage to the institutional ABCs — attendance, buildings, and cash.

Leviton: You did rise to become the senior pastor at First Congregational Church. What did you achieve during your tenure?

Pinkard: Institutions can take both life-giving and life-diminishing forms. My goal as pastor was to ensure that our ministries were vital and full of life, and the congregation and I accomplished that to a large extent.

We developed “life groups” of eight to ten people who took on projects in the neighborhoods. They adopted schools, worked on literacy or environmental issues — whatever was needed. We would all come together for classes and worship. We trained in nonviolent communication. We reached across every divide. We allowed full voting membership in the church to everyone: Muslims, Jews, pagans, atheists, Buddhists, new-age people — they all became part of the process. We accepted the challenge from atheists and agnostics to live the Gospels we preached. We didn’t run from conflict. We were committed to dangerous, daring, and difficult love.

We created a radical community of humble service. For single moms who were going to college and working a job, we had people who would take their children to school and pick them up every day. If someone’s car broke down, we fixed it. We paid people’s debts and then taught them how to stay out of debt in the future. We called people to an “economy of love.” It was like a mini Rolling Jubilee — the organization that grew out of the Occupy movement that buys up debt for pennies on the dollar, then forgives it. We told the debtors, “You repay the kindness that you have received by doing something for someone else, not for us.” We got involved with the Bay Area organization Genesis, which was working to keep transit available and affordable for poor people. We fought to put empty foreclosed houses into a public trust, so they could be utilized to house the houseless. We worked on the issue of police brutality in Oakland. We went to city-council meetings, raised our voices, and allied with the families who needed help.

There was so much more that we could have done. We could have turned the church basement into transitional housing for women with HIV, or people with substance-abuse issues, or transgender teens. We could have made the building useful all day and all night, instead of just during services and meetings.

Leviton: Why did you resign?

Pinkard: The truth is, after almost eight years, first as associate pastor and then as senior pastor, I’d begun to feel depleted by the institutional ABCs, and to feel as if my role in the church was in conflict with my soul. I grew more in the years that I served as pastor there than at any other time in my life, and I facilitated more growth during my tenure than anywhere else I have ever served. But, honestly, I didn’t have any investment in preserving an institution for its own sake. For me, churches exist only to serve people and planet. The church is not an empire, a way for leaders to build monuments to themselves, for congregants to take pride in the curb appeal that a lovely edifice affords. The church is not a building, nor is it a professional class of “holy people” who keep things running, or personalities who fill stadiums — none of that. The church is an extension of Christ — literally Christ’s body — and an alternative to the militaristic, consumerist, alienated way of life that has become the norm.

I fundamentally believe that God’s love manifests itself in the world on the “yeast principle”: it springs up everywhere that the Spirit is fully alive. God doesn’t try to create empire or theocracy. That is what we don’t seem to get. If we were all totally open to the Spirit of Life, it would send us out into the world to replicate that Life. One sign that a church is full of the Spirit is when it begins to replicate the Life of God in the world. Churches are too often like black holes — they want to draw people in and jealously hold on to them the way a black hole draws everything into itself, even light. The Kingdom of God generates light and energy like a star and sends it outward.

Americans, and American institutions in particular, are adept at evasion and denial of suffering. Not only our government but our churches and mosques and synagogues and temples are full of people who are good at looking the other way.

Leviton: People talk about building bridges between different ethnic and racial groups, but we don’t challenge the idea of our separateness.

Pinkard: I call the work of challenging that separateness “interculturalism.” Multiculturalism merely places cultures side by side without seriously questioning the structures of power and dominance that make authentic community impossible. Interculturalism demands that we interrogate our own cultural identities and our privileges while simultaneously working to overcome internalized oppression. Through deep, honest engagement with each other, we can transform the forces that create suffering and work against life. The great author James Baldwin said we should take whatever’s bullwhipping us and killing us and use it to connect with every other living being.

Leviton: You’ve written that you are tired of people doing something for someone else with an eye toward their own self-interest.

Pinkard: Yes, multiculturalism, as it is generally practiced in this country, is love as an investment, a bargain in which you get something in return. Jesus wasn’t offering love as an investment. The Gospels don’t have anything to do with success or upward mobility. Multiculturalism is there to advance some agenda that might not have anything to do with truly freeing anybody. We’re not going to do this work — of bringing people together, of stemming the tide of ecological abuse, of dealing with income inequality — without having something inside us change. Before I even get to my interaction with you, I need to examine my own self-interest. That’s what resurrection means to me: being able to rise above self-interest and the interests of your group. For me resurrection is about laying down our weapons and getting up off our assets. Resurrection is not merely about whether Jesus is dead or alive, in the tomb or not. In Romans the Bible says the same spirit that raised Jesus from the dead can quicken our mortal bodies to life. We can leave our cemeteries, abandon the deadness and the death-dealing nature of our lives. We can rise above the life-limiting forces that hold us down. For me, that’s resurrection: crossing over from self-interest to true solidarity.

Leviton: You have preached a lot about the Hebrew prophets — Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel especially. I’m interested in how you connect these ancient prophetic voices to the concept of “revolutionary suicide.”

Pinkard: My essay “Revolutionary Suicide” was an effort to do some prophetic preaching, which consists simply of telling as much truth as I can bear, and then a little more. We live in a country in which words are used mostly to lull us to sleep, not to wake us up. The air is so heavy with rhetoric, so filled with soothing lies, that it feels to others as if I were doing great violence when I seek to disrupt the comforting murmur.

I am distressed about the overwhelming torpor and bewilderment of so many Americans. When the economy crashed in 2008, we learned that our government might be an immune system for wealthy capitalists, but it is not an immune system for us. Our puzzlement and disappointment about the state of our country reveals something that we do not want to know about ourselves: namely, that we are afflicted with both the world’s highest standard of living and the world’s emptiest way of life. The American way of life has failed to make people happier, but we do not want to admit this. Instead we persist in believing that the emptiness is the result of some miscalculation in the formula and can be corrected; that the bottomless and aimless hostility that makes our cities dangerous is created by a handful of troublemakers; that the lack of passionate conviction, of unrelenting vitality, is the result of the government or the corporations or the military or the National Security Agency. We are trapped between what we would like to be and what we actually are. And we cannot possibly become what we want to be until we ask ourselves why the lives we lead on this continent are so empty, so tame, and so ugly.

I believe it’s possible for all of us to practice truth-telling, which is a form of revolutionary suicide in a culture that increasingly targets and punishes truth-tellers. We are desperate to reestablish our connection with ourselves, with one another, and with the planet, but this can begin to happen only when the naked truth is told.

The prophet Ezekiel is the embodiment of the naked truth. He saw dead leaders, dead systems, and dead people, and he could not keep silent about it. Part of our prophetic task is to talk about the pervasive deadness in our own lives and in our world. We are being called to revive symbols, metaphors, and rituals that can serve as vehicles for redemptive honesty. When I was pastor of First Congregational Church, we held a symbolic funeral for the American empire. We invited people to bring their deadness and the deadness in their communities and to eulogize it as a way of expressing that the whole imperial arrangement is embodied not just in the government and in corporations but also in us. Then, after the public burial, we put away the sadness and reminded each other that the problems that beset us aren’t insolvable. The world is not full of scarcity, and we do not have to scramble to get our share. Our hurts are not as endless as they seem. Hope doesn’t have to be stifled by frustrated cynicism. Peace is possible when we tell the truth about our hurts and our hopes.

In Matthew 10:7–8 Jesus commissions his disciples — in other words, us — to recruit others into the countercultural community of God. He says, “And as you go, preach, saying, ‘The kingdom of heaven is at hand.’ ” Jesus is not drawing us into an institution. He’s telling us to go out into the world and carry with us the good news of God’s community.

Leviton: You’re saying we need to become evangelists?

Pinkard: Yes, but being evangelical does not mean traveling to some foreign or “other” place that needs to be “taken.” Rather it means offering an alternative in every place where the death-dealing powers rule. It means modeling alternative communities in the midst of conventional communities. We are trying to create space for the Spirit of Life amid death. We can rupture the dead culture with our presence, with our own irrepressible lives.

In Luke 10:4 Jesus urges us to travel lightly: “Carry neither money bag, knapsack, nor sandals; and greet no one along the road.” He is advising us to resist attachments to power, status, security, and wealth. The opposite of rich is not poor; it’s free. The more weighed down we are, the harder it is for us to move when the Spirit says move. When we’re encumbered by baggage such as credit-card debt, we are unable to follow the Spirit’s lead.

We also need to expand our notions of family and community toward revolutionary solidarity that crosses lines of difference. The American empire wants to keep us tied exclusively to the nuclear family. Those of us in queer relationships have broadened the definition of family. The Creator has invested all of us with the capacity to cultivate deep bonds of love and compassion for anybody and to enter into solidarity with all life on this planet. We can make a circle with no one outside of it. We can define all life as one interconnected community. This is a radical act in a culture driven by self-interest.

Jesus is not coy about the fact that the work of His disciples will be dangerous: “I send you out as lambs among wolves” (Luke 10:3). The closer we get to embodying the real love of countercultural, feral Christianity, the more trouble we will encounter.

Leviton: Why did the radical prophetic message of Jesus and the Hebrew prophets get so obscured by religious institutions?

Pinkard: Novelist Henry James called America a “hotel civilization,” where you never see the people who clean up your mess. We are so obsessed with comfort and contentment and convenience that it is difficult to talk about the pervasive suffering in the world. Americans, and American institutions in particular, are adept at evasion and denial of suffering. Not only our government but our churches and mosques and synagogues and temples are full of people who are good at looking the other way.

Also religious institutions have largely been co-opted by the state and so do not have the capacity to fulfill their original function of disturbing the peace. We have lost our cutting edge, and we are no longer capable of issuing a substantive critique of the death systems of this culture. Now we are obsessed with personal piety and prosperity.

Leviton: Isaiah 58:6 says, “Is this not the fast I have chosen: to loose the chains of injustice, to untie the yokes, to let the oppressed go free?”

Pinkard: Religion is that, or it’s nothing. People say, “I don’t know what to do.” Micah 6:8 tells us what to do. We are to “act justly, love mercy, and walk humbly with God.” It’s not a mystery. When we read the Gospels and hear Jesus saying, “Give away your possessions,” and, “Love your enemies,” and, “Forgive those who intentionally hurt you,” we say, “This is terrifying.” Why? Because it is so much easier to say, “I haven’t had a cigarette today,” or, “I’ve had only one glass of wine,” or, “I go to church every Sunday,” or, “I serve meals at a homeless shelter,” than it is to love your enemy or to take everything you don’t need and give it to the poor. We don’t want to simplify, to stop consuming (unless we can toot our progressive horns about it). To love wastefully and give recklessly — that scares us.

But our goal is progress, not perfection. If we can’t love our enemies, we can start by loving the people who love us back and then move on from there to people we find a little suspect, and then to the people we don’t like at all. Resurrection and salvation are about the kind of love that overcomes our own self-interest. If I’m interacting with the world primarily as an investment and looking to make a good return, I’m losing my life. Real relationships aren’t investments. Community is not a contract; it’s a covenant, the way the Jewish Sabbath is a covenant: Stop making money for a day. Stop with the contracts. Stop shopping.

Leviton: You’ve written that “the poor are both a required element and a natural byproduct of capitalism.” Isn’t capitalism intended to spread its benefits throughout society, even if its rewards may be out of balance at times?

Pinkard: There is a seductive beauty in the idea that everyone has equal economic opportunity under capitalism. First, it allows the wealthy and powerful, the owning class, to feel justified in their position. They can believe their privilege is based on their own hard work, or the hard work of their ancestors. Second, just enough of the poorest are desperate enough to think that, despite all evidence, they can become rich. Most poor people don’t believe this, but they also don’t have enough resources or popular support to bring about real change, or else they are convinced that they are indeed unworthy and sometimes even work toward their own destruction. Third, the so-called middle class is led to dream of becoming rich and to fear the encroachment of the poor.

It’s a wonderfully complex set of illusions. The fact is that economic growth — the goal of capitalism — is always followed by an increase in the disparity between rich and poor and a withering of the middle class. The United States has almost the highest rate of poverty among the industrialized Western nations. Our government provides little or no safety net for those who have fallen through the cracks of the system. Charities and welfare programs established to help the unfortunate do not have the power or resources to lift people out of poverty, and they never will. Meanwhile the government conjures the illusion of opportunity while keeping upward class mobility to a minimum, and the rich get richer. Wealth carries not only purchasing power but also social and political power. It takes a large amount of wealth to alter the political process, and until you and I reach that highest level, our efforts are easily negated by those who have the most money.

Capitalism abhors the equitable distribution of wealth. Any social program that could improve the economic standing of a significant number of people on the bottom is doomed. Low-income communities are provided with the worst educational resources. Even if the poor were able to surmount all challenges, they would only end up changing places with those above them. The middle class would be squeezed downward, ensuring that the number of poor people would stay the same, if not increase. Social programs can soothe immediate suffering, but they will never achieve social justice, no matter how well funded they are. Individuals can change their class positions, and the quality of life for those at the bottom may be slightly improved, but economic justice will remain elusive. Only a change in the economic system will remedy this.

Leviton: Speaking of changes in the economic system: There is a worldwide movement demanding reparations for slavery in the form of debt forgiveness and monetary compensation. What’s your position on this?

Pinkard: There are a lot of different approaches to reparations. The one that inspires me consists of three major components: (1) apology for wrongdoing that has happened and/or is happening; (2) material and cultural redress related to these wrongs; and (3) structural change to ensure that the same kinds of wrongdoing don’t happen again.

Reparations begin with listening and responding to the claims and demands made by those who have been on the receiving end of racial domination. This means that people of color set the agenda, something that makes white people of all political stripes uncomfortable. White supremacy continues to manifest itself in this way, even among leftists.

Reparations are not a one-off payment but an ongoing process focused on the transformation of society, not just individuals. I’m not saying that individual transformation doesn’t matter, but as long as white supremacy exists, we all remain captives of our positions within it, which for white people means maintaining an oppressor identity.

Reparations can’t seek just to level the playing field or to swap out the players in different positions. To quote Robin Kelley from his beautiful book Freedom Dreams: “Imagine if reparations were treated as start-up capital for black entrepreneurs who merely want to mirror the dominant society. What would really change?”

Leviton: Do you feel reparations are necessary?

Pinkard: Yes, because the wealth some people have has been taken from others. This is an important insight during an era in which people are saying racial discrimination is over: “We’re all the same now; we shouldn’t look at race.” Reparations challenge the ideologies of equal opportunity and meritocracy and offer an alternative to charity or welfare or debt forgiveness — all terms that assume the assets being redistributed were legitimately acquired, and therefore the redistribution is generous and benevolent and should be met with gratitude. Who should be asking whom for forgiveness?

Reparations need to start with an apology, but an apology is meaningful only if you understand why it is necessary and support its being made. And it must lead to consequential action. To simply continue with business as usual would make the apology a lie.

I hear talk about reconciliation or restorative justice, but there is a lot of work that has to happen for reconciliation to become a real possibility. Otherwise we have what theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer called “cheap grace.” Some people are ready to address the relational aspect, but when you bring up money, that is the end of the conversation. Others talk about material reparation — which usually amounts to a one-time payoff — but are not willing to address internalized superiority, entitlement, power sharing, agenda setting, and cultural assumptions.

Leviton: Did you have a connection to the Occupy Oakland movement? It had a reputation for being more volatile, confrontational, and militant than Occupy movements in other parts of the country.

Pinkard: Occupy Oakland was good in many ways, but there was a downside. Some people got into nonproductive skirmishes with the city council, the mayor, and the police. There was an adolescent attitude. There is no room for high-school behavior when combating a death culture.

I’ve lived in West Oakland for about fifteen years. During the Occupy protests young white anarchists came into our communities and lived as squatters in empty houses without any consciousness of the fact that those were the foreclosed homes of people of color, mostly older African Americans who had invested in their neighborhoods for decades. The squatters had no knowledge of the suffering those boarded-up houses represented. These young anarchists misunderstood the history and power of anarchist movements. They displayed a sense of entitlement, spray-painted slogans on the very train station where the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters — the first black-led labor union — was formed. Can you see the irony in that? They never “tagged” liquor stores, where men and women who can barely stand up buy two-ounce bottles of alcohol with spare change. These stores, which are certainly not black owned and operated, sell booze and cigarettes and lottery tickets and pornography and junk-food items that foster addiction and illness. Pretty much everything sold in these stores degrades customers’ health to profit people who often do not even live in the community. But there was no tagging there. You didn’t see any young white anarchists tagging the deathtrap crack houses owned by absentee slumlords. The squatters were an extension of the gentrification that’s been destroying black communities for years. The racism in the anarchist movement is evident.

For me, churches exist only to serve people and planet. The church is not an empire, a way for leaders to build monuments to themselves, for congregants to take pride in the curb appeal that a lovely edifice affords. The church is not a building. The church is an extension of Christ — literally Christ’s body — and an alternative to the militaristic, consumerist, alienated way of life that has become the norm.

Leviton: When the anarchists confronted the police in your neighborhood, they didn’t know the history of how people of color have been dealing with police brutality there for decades.

Pinkard: Yes, the residents of West Oakland were coming from a specific local history, and Occupy anarchists weren’t engaging with them. Since then, I’ve seen some cross-fertilization between people across traditional divides, but there are still different priorities. For poor people of color, defacing Bank of America buildings is probably not a priority. We need relief from police brutality. We need relief from dumping and toxic waste. We need relief from the unjust distribution of resources that perpetuates food insecurity. Our soil is so full of toxins that we can’t grow food in it. The Red Star yeast plant was operating in Oakland for a hundred years, pumping noxious gases and probably carcinogens into the air, elevating asthma and cancer levels. These are the neighborhood priorities, not writing a letter to demand a meeting with JPMorgan Chase chairman Jamie Dimon or playing a game of cat and mouse with the robber barons of Bank of America and Wells Fargo.

I can appreciate the spirit of anarchism and the work and presence that anarchists seek to bring to our collective movements, but immature college kids jumping on a bandwagon are not helping, especially when they are going to return to UC Berkeley in the fall to study Slavic languages. Even if we were all on the same page, black communities don’t need seasonal help from people who have no history or investment here. Unfortunately those anarchists aren’t the only progressives who are guilty of this. Too often we progressives believe we know more about other people’s pain than they do, and we feel sorry for people who actually feel sorrier for us. White American progressives especially need to understand this. Progressive does not always mean productive.

During the Occupy protests young white anarchists came into our communities and lived as squatters in empty houses without any consciousness of the fact that those were the foreclosed homes of people of color, mostly older African Americans who had invested in their neighborhoods for decades. The squatters had no knowledge of the suffering those boarded-up houses represented.

Leviton: In one of your essays you examine public reaction to the 2009 killing of Oscar Grant in the Fruitvale BART station by policeman Johannes Mehserle. Grant was shot in the back while lying on the ground. There was a cry for justice, which for many meant the harshest possible punishment for the officer, but you saw a bigger, more complex issue.

Pinkard: I knew that essay would make many people angry: black nationalists, anarchists, church people, white progressives. We can talk about Mehserle and Grant as individuals, but individuals live inside a system and serve that system. We’re all implicated in it. The drumbeat starts, and people start marching. Human communities often demand we find a single person who then becomes the scapegoat for everyone. Officer Mehserle, in this sense, becomes the surrogate of our collective neurosis. We are all implicated in a system that does not work.

Whether we use guns or schoolbooks or church bells or department-store mannequins to prop up the system, all of us — rich and poor, gay and straight, liberal and conservative — serve an imperial agenda. We are the problem, and that’s upsetting to people. I’m not dismissing or trivializing the actual events. I’m not minimizing police brutality. Police brutality has been a permanent fixture in America since the beginning. It’s what got the Founding Fathers so much free land and free labor. But the focus cannot be just on one police officer’s culpability and trial and sentence.

I’m stunned by the lack of a national movement to protest the killing of black youths, given the number who’ve died from Florida to California: Alan Blueford, Trayvon Martin, Oscar Grant, Jordan Davis. These murders aren’t happening because of the politics or policies in any one city or state. It’s a national problem.

Part of the problem is the internalized oppression in black communities. The plantation is within us. For me the question is “Do we love ourselves enough to fight the forces of death and to surrender completely to love?” There’s a pervasive hopelessness in African American communities, a collective depression and post-traumatic stress. We get decimated and eaten alive over and over again. Sadly some of us have bought the lie and feel we deserve it, and we devalue our own lives and legitimize and perpetuate our oppression. We let internalized oppression anesthetize and defang us and render us docile and innocuous.

We each have an internal matching fund of oppression — we meet the institutions’ attempts to suppress revolution with our own efforts. In Oakland people protested the wars of profit in Afghanistan and Iraq and all the money private contractors were making, but nobody — black or white — marched against the decades-long, CIA-engineered funnel of drugs and guns into our communities for the express benefit of the American government and elites. Drugs and drug violence were used to quell black activist movements, to break the back of the revolutionary spirit in poor black communities and lay the foundation for the prison-industrial complex, “black-on-black crime” and “gang wars.” Drugs took away black social capital and thriving neighborhoods and communities and the trust that enabled us to organize against external forces of death. Marcus Garvey said the reason we can’t organize is that we don’t trust each other.

For me it comes back around to spiritual impoverishment. I’m not someone who believes we can just get some funding from President Obama and solve our problems. I’ll say it again: We are deadened and need to have a funeral for the deadness in us and in our culture. Bury the deadness, and then we can come fully to life. We can’t transform our communities if we can’t critique them and make substantive changes.

Leviton: White people in the media and everywhere else are always telling poor people of color to pull themselves up by their bootstraps — all the worn-out prescriptions of more than a hundred years of racism. Is it infuriating to hear that?

Pinkard: Yes, white people came up with this racist rhetoric because the truth is we were too busy pulling your bootstraps up — picking your cotton, chopping your cane, plowing your fields, raising your children, cooking your food, bearing your beatings and brutality, and, quite frankly, laying the foundation for the stolen country that you are so proud to own. But black people have to examine how we’ve absorbed the “bootstrap” rhetoric and how we continue to serve the master. As feminist Audre Lorde said, “You cannot dismantle the master’s house with the master’s tools.” And we are borrowing the master’s toolbox. Some people of color spend all of their energy using those tools to build an American dream house where they can eat at the welcome table, only to find that many of the people at the welcome table are still impoverished at the deepest levels. But our obsession with the master’s tools, with upward mobility and fitting into the system, makes sense, because we have been disenfranchised for so long. Black people got the right to vote only fifty years ago. We were being lynched sixty years ago. After the end of the formalized apartheid of slavery, we had twelve years — from 1865 to 1877 — for Reconstruction, and then we were reenslaved through the peonage system [in which people are bound into servitude by debt]. Former slave owners could pull black people back into a life of forced labor by criminalizing everything we did — such as spitting in public or looking at someone the wrong way — and they could put us in prison, where they could work us to death. Under slavery, at least the slave owner had a substantial investment in his slaves and didn’t want to kill them. From Jim Crow until today, the prison-industrial complex has served as the ultimate plantation.

Leviton: What are some of the ways “internalized oppression” manifests itself in all our lives, whether we are Christian or Jewish or Muslim, a person of color or white, a native-born American or an immigrant?

Pinkard: The world in which we live is full of pain and cruelty, and everyone born into it absorbs some of that pain and cruelty, gets shaped by it, and perpetuates it. Internalized oppression is akin to what Freud calls the “repetition compulsion”: the reflexive impulse to inflict on others the pain that we have suffered. To live in faith is to believe that God’s love is alive in us and can help us transcend this compulsion.

Leviton: When President Obama was elected, was it a major event in the black community?

Pinkard: Most of us didn’t think a black person would be president in our lifetimes, so it was historically and culturally significant. Some black people wanted to attach other significance to it. Some saw it as the fulfillment of a revenge fantasy: now we had the power and could do what we wanted. Others saw it as salvation: God had intervened and given us a prophet who would transform us. But you can’t be a prophet and be the president of the United States. You can’t even be a true centrist and be president. Whether the president is black or white, the office is intended to serve imperial interests. The real prophets — Jesus, Ezekiel, Jeremiah, Obadiah, Amos, Joel — didn’t critique the “president” of their times, because they didn’t expect him to lead from a prophetic vision. Obama is a socialist? Get out of here. Obama does the bidding of the rich and powerful! I believe that, as a person, he’s kind. He was unhappy about the foreclosure crisis. He wants to offer healthcare to more people. But he was bought and paid for by Wall Street interests before he ever sat in the Oval Office. You don’t get to be president without the help of corporations, so you’re never going to challenge them; you’re going to make deals. That’s why bankers aren’t going to jail, and banks are paying a pittance in fines.

Our foreign policy is based on corporations going into third-world countries and promising development in exchange for permission to extract resources. But the development never happens on the scale they promise. Often all they really do is pay off the local dictators — or assassinate the ones who won’t cooperate. And if they can’t plunder the natural resources by any other means, they start a war.

There’s no way to be radical inside this system. It’s like Bob Dylan sang: “You gotta serve somebody.” The politicians are always serving somebody. As long as any of us are a part of this system and receiving its benefits, we are serving it.

When I was pastor at First Congregational Church, something happened to me. The Spirit gripped me, and I became willing to take more risks to help myself and others flourish. I have taken only baby steps, but I want to live the Gospel that I preach and sing about. Every day I realize how addicted I am to the death systems of this culture, and I want to be free. Malcolm X said, “If you’re not willing to die for it, take the word freedom out of your vocabulary.” I understand that the consequence of a life of unapologetic dissidence is often the death of some part of us, but that death leads to new life. That tradition of dying in order to live is the Gospel I love.

Internalized oppression is akin to what Freud calls the “repetition compulsion”: the reflexive impulse to inflict on others the pain that we have suffered. To live in faith is to believe that God’s love is alive in us and can help us transcend this compulsion.

Leviton: Is that where you were coming from when you wrote “Revolutionary Suicide”?

Pinkard: Yes, but it’s not a death wish; it’s a life wish. It’s radical to die for the cause of freedom, but even more radical to live for it. In her poem “Be Nobody’s Darling,” Alice Walker writes, “Be an outcast. / Qualified to live / Among your dead.” In other words, we may be ostracized in life, but we’ll have a place with our forebears and everyone in the world who has fought for freedom.

Leviton: You call for “the destruction of our attachments to security, status, wealth, and power.” Isn’t that a formula for becoming powerless and destitute?

Pinkard: As a culture we are in a nosedive toward death, and to interrupt it, we must opt out of the capitalist systems that are killing us and decimating the planet. Although we might criticize systems and bemoan their negative effects, we do not often focus on the degree to which we rely upon them. We balk at any course of action that truly threatens the status quo, because a confrontation with the system is going to cost us our comforts and our reputation and possibly our lives. But we have to stop shopping at the bargain counter of the American company store, where we exchange substance for more security, more status, more wealth, and more power. It is nearly impossible to be a prophet with a wallet full of credit cards. Resistance to the system means social death and loss of identity, but it is also a struggle for life. It is not the futile hope for a better day, the self-indulgent staking out of a political position, or a reckless descent into disorder. It is self-determination with integrity. It is the assertion of life without apology. It is the willingness to defend what we love with our lives.

In effect, this acceptance of the end of our lives as we have known them enables us to move away from another kind of death — the social, political, and economic conditions that leech the meaning from life, devastate relationships, and lead us to despair. We need to build interdependent communities that trust people over money and collectivize both risk and security. We need to switch from putting our faith in money to putting our faith in each other.

As a nation Americans have an entrepreneurial identity, but what would it mean for our capitalist system to become truly entrepreneurial? If we capped personal wealth at a billion dollars and limited the size of corporations, would it really take away our incentive to work hard, or would there be a revitalization of small business because people wouldn’t have to constantly compete with the super-rich? What if some of the vast wealth that a few individuals have accumulated went into business education for the many? McDonald’s might collapse, but a million individually owned restaurants would rise up to take its place. And there would still be workers, because there will always be those who don’t want the stress and strain of owning a business. Actually my favorite alternative business models are the ones in which workers collectively own the business, making decisions democratically and sharing both the risks and the profits. The new term for such arrangements is “workers’ self-directed enterprises.” If we had more of those, we would have happier, healthier workers.

But no frontal assault on capitalism can accomplish this. Protests, policy changes, organizing, and even revolt will all be crushed, corrupted, or co-opted. We need a viral assault: simple mechanisms that can replicate quickly and replace big business with economies of love. We need meetings that are as common as AA meetings. We need to take advantage of the Internet. We need tools for economic “homesteaders.”

When I tell people this, they sometimes accuse me of wanting to take away people’s freedoms. They think of capitalism as the source of this country’s greatness, and when I criticize it, they say I sound like the Taliban in Afghanistan. A short, fat, black, lesbian pastor is attacking the American way of life! How dare she! She doesn’t have a degree in economics! She’s not an academic! There’s a hierarchy these people want to preserve. They believe ordinary citizens aren’t qualified to take part in the economic debate.

Leviton: A few days ago I read a selection from the Torah — the Hebrew Scriptures — about the jubilee years, when ancestral lands are returned, debts are forgiven, and indentured servants are freed. How can any religious person read that and think God is in favor of capitalism?

Pinkard: Yes, it reads like an attack on modern banking. God says, “This is not your land; it’s mine. This is not your money; it’s mine. You are just the stewards of it.”

Christianity is a branch off the tree of Judaism. Many Christians don’t realize that Jesus came out of the tradition of the Hebrew prophets.

Leviton: You mentioned AA. You’ve already helped create an AA-style program designed to assist people in opting out of the system: Recovery from the Dominant Culture, or RDC. What’s it about?

Pinkard: In a nutshell, RDC is like a twelve-step program that says we’re all recovering from an addiction to this culture we were born into. What my colleague Nichola Torbett and I have tried to do is develop materials that describe a way out of our cultural addiction.

RDC has enabled me to understand more fully how I have been shaped by the values and beliefs of the culture in which I live. Several members have told me it has enabled them to work more effectively in other twelve-step recovery programs, because of the connection RDC makes between individual lives and institutions. Other Anonymous programs don’t explicitly take into consideration the relationship between an addicted society and individual addicts.

For instance, I am a food addict. On a bad day I will knock your mama down for a doughnut and miss the revolution because I am getting high on flour and sugar. Thankfully, I belong to a recovery program for food addicts. But because I am also in the RDC program, I can better understand how my consistently eating more food than I need subverts the work of food security and justice in the world. This reinforces my commitment to addressing hunger in the East Bay through Share First Oakland, an organization I cofounded.

There are participants in RDC grappling with other life-limiting habits, such as hoarding money and resources that could be shared or engaging in conspicuous consumption. One member shared her inheritance. Another sold some of her belongings and gave the money to a community-based organization. Although there is no permanent “cure” for the socialization we have received, we are finding that it is possible, with the help of a Higher Power and the support of a recovery community, to live a sane and joyful life of usefulness.

Leviton: What are the challenges you’ve encountered as an openly gay woman?

Pinkard: I could talk about the collective pain and trauma of queer people, but I won’t, because I have grown tired of describing my suffering and the suffering of my various tribes: black, lesbian, female, fat, impoverished. My suffering cannot be addressed outside of the context of a suffering world. Yes, I hurt. Everyone hurts. What is crucial is that we use our hurt to connect with others rather than view them as the opposition. Now, that is radical: to refuse to see the so-called opposition as opposition, because we are a part of everything that we indict.

The bottom line is that we are called to lives of compassion. We are called to the work of liberation through love. That calling is the only thing in life worth suffering for. We cannot abide any suffering other than that which is required to change the world.

Leviton: Has there ever been a time when you lost your faith?

Pinkard: Through it all I’ve continued to love Jesus and the prophets. I love the church. I am a product of it, and I have spent my life serving it in various ways. The problem for me is that institutional church programs and denominational structures are too often removed from real, radical, biblical discipleship. The institutions often become bulwarks against the movement of the Spirit and act to preserve old patterns of power ill-suited to the real message of our faith. And I have to admit that Christians sometimes scare me. I even scare myself. [Laughs.]

Once, in church, a preacher was talking about “fornication” — you know, sex outside of marriage — and a young girl came to me and said her first experience of sex was being raped at knifepoint by her uncle on her grandmother’s kitchen floor. What was it like for her to be preached to about fornication? When I was younger, I believed that if something happened, it was because God had willed it, and if it didn’t happen, then God had not willed it. I do not believe that anymore. I do not believe that God steps in to stop the car from hitting the wall or to make the car hit the wall. Into my early thirties I was constantly trying to resolve the question of why God allows suffering and evil in the world. I have more of a process theology now, meaning that God changes as the world changes. We are growing, and God is growing. God herself is in process. God is suffering, too, because God loves creation and expresses that love through compassion and solidarity. God was with every Jew who went to the camps. God was with the child who was raped. God is for life and will use every single thing at God’s disposal — which is love, basically — to move creation toward life.

I believe God’s heart is broken every time we waste planetary resources, every time we do harm to each other, every time we march the zombie death march, every time we cooperate with the death culture. God is striving with us. God is present, whether you just lost your mother to pancreatic cancer or your country just killed people at a wedding party in Yemen. God went to the camps, and God was lynched and shot and tortured. And still God is loving. It’s not our job to read Isaiah and then go sit at Starbucks and talk about what a sad place the world is. It is our job to collaborate with each other and activate that love.

Leviton: What happens inside you when you read in Scripture that homosexuality is an “abomination”?

Pinkard: The same thing that happens when I hear that all white people are “blue-eyed devils.” That was one interpretation of Islam, but it wasn’t Islam.

I went to college in Virginia, and the religion I was exposed to there, in the heart of the Bible Belt, supported militarism, triumphalism, consumerism, and more prisons going up everywhere. They said, “God is calling for us to build prisons and to found the Christian Broadcasting Network.” Their God sponsored artillery shells — and hated homosexuals. When I was eighteen years old, I began to wonder who benefited from that sort of thinking. What was at stake? For the first time I was experiencing fundamentalism without the “fun.”

The Pentecostal churches where I’d worshiped in St. Louis had been a lot of fun. I have often said that African Methodism gave me the language of justice, but in high school I felt drawn to Pentecostalism because it gave me the language of ecstasy. And it’s good for black people, who have been so oppressed, to experience ecstasy, to learn to love themselves despite fundamentalist rhetoric, and to express that self-love through reclamation of their bodies. Yes, people may not have been talking about it, but there was a fair amount of sex in those St. Louis Pentecostal communities, too.

I liked some of the people I met in Virginia. I loved some of the girls. So I tried to fix what I saw as the flaws in fundamentalism, the way you might get a patch to fix a computer program. But eventually I realized that the whole framework had to go. There’s nothing conservative about God or about the Spirit of Life. Empires conserve and hoard resources. God doesn’t conserve.

We should worry less about going to hell and more about wasting the life we’ve been given here. This life is hell if you don’t figure out what to do with it that makes you fully alive.

God is striving with us. God is present, whether you just lost your mother to pancreatic cancer or your country just killed people at a wedding party in Yemen. God went to the camps, and God was lynched and shot and tortured. And still God is loving. It’s not our job to read Isaiah and then go sit at Starbucks and talk about what a sad place the world is. It is our job to collaborate with each other and activate that love.

Leviton: What kind of projects have you undertaken since you left First Congregational Church?

Pinkard: I’m on the board of directors for the Seminary of the Street, which is a school for activists who want to transform their communities and embody God’s love. Out of the Seminary of the Street grew the West Oakland Reconciliation and Social Healing Project, which is an experiment in true racial and economic reconciliation. We initiate group conversations in which white people and people of color share stories about their lives and commit to staying at the table beyond the superficial “Can’t we all just get along?” kind of reconciliation. For example, in 2008 gay people were saying that black people were the reason Proposition 8, which outlawed same-sex marriage, had passed in California. They thought that black churches had encouraged their congregations to vote in favor of Prop. 8, and many of them had, but so what? We cannot start a blame campaign and allow white people to use their disappointment about the passage of Prop. 8 to fuel latent racism that results in more separation and divisiveness. We’re not going to support that. So I said, Let’s get white lesbians to work with formerly incarcerated Latin and African American men. Let’s work together both on marriage equality and on the negative impact of felony convictions, which prevent formerly incarcerated persons from finding gainful employment. In this way both groups will work for justice and learn to be in solidarity, starting with genuine care and concern for each other’s suffering.

Leviton: You’ve dedicated much of your life to addressing inequality and racism in our country. How have you managed to maintain relationships with your own loved ones over the years?

Pinkard: When I think about my relationships with Mama and Daddy and Grandma and the people who nurtured me in the faith, I cannot help but be reminded that I am a small part of a great tradition of struggle for decency and dignity and freedom. This tradition is not something that I can simply inherit. If I want it, I have to work for it. I also believe that what we have loved well in our short lives constitutes our legacy, and that we become who we are, with all our flaws and faults, because somebody somewhere loved us and cared for us and sacrificed for us. I have loved some people, and some people have loved me, and that has saved my life.

At difficult, demanding times, I have sometimes felt misunderstood and marginalized, and I have struggled with resentment and isolation. On the rare occasions when I feel it even now, I realize that in some ways it is a painful but necessary stage of my journey toward awakening and a more abundant life. When I was about fourteen years old, for reasons that I could not explain to myself or to others, I suddenly felt that I did not belong anywhere. One minute I was a member of a family, of a church, of a choir, of a debate team, and the next I felt as if, in other people’s eyes, I was moving to the edge of the world. I came out as a lesbian to my mom, who said she’d already known about it for a long time. But this movement to the edge was not just about my sexuality. To a certain extent that was the least of it. As early as fourteen years old, I had some faint recognition that the world for which I was being so carefully prepared — upward mobility, acceptance, and respectability — was being taken from me by the grace of God.

At the age of sixteen I left my family’s church. Thankfully my mother never prayed that I would move back from the edge and toward the center, but other members of my family, my church, and my communities did. Eventually they stopped praying for me, because they realized that it wouldn’t do any good. They gave me up to this force that is beyond all of our control, and, as James Baldwin said, that was “a fantastic and terrifying liberation.” Now, when people ask me how it feels to be an African American, Christian, lesbian woman — ever searching, ever yearning, often with very little money — some loud, laughing part of me says, “I hit the jackpot!”