A slightly longer version of this interview appeared in the August 1985 issue of The Sun.

— Ed.

On Columbus Day 1970, more than two hundred San Francisco hippies set off in a caravan of remodeled school buses on a cross-country pilgrimage. In the lead bus was Stephen Gaskin. A former Marine and college teacher, he’d started experimenting with psychedelics in the 1960s and had begun holding Monday-night discussion groups at San Francisco State College on drugs, religion, honesty, and peaceful cultural revolution. By 1970, Gaskin’s most dedicated followers were ready to start a community of their own, based on self-reliance, voluntary simplicity, hard work, and faith in God.

In Tennessee they bought seventeen hundred acres that became known simply as the Farm. Members of the Farm, who eventually numbered fifteen hundred, signed over all their worldly goods upon joining. The Farm developed into one of the nation’s most ambitious and successful communes, with its own schools, health clinic, soybean dairy, bakery, and work crews for carpentry, farming, and so on.

It must have been quite a shock to the locals to find those brightly painted school buses, looking like the spaceships of an extraterrestrial invasion force, in their backyard. But the Farm soon established bonds of friendship with its neighbors, often sharing information, farm equipment, and manpower. Gaskin recalls going to the bank to secure the initial loan to buy the land: “The bank guy said, ‘It’s not just that you’re these out-of-town hippies we’ve never seen before; it’s also that it’s the largest loan that anyone’s ever asked for from this bank!’ Since then, two of those banks have folded, and we haven’t. No one would have predicted that.”

Over the last fourteen years, approximately 150,000 visitors have passed through the Farm’s front gate, many simply to share in the vision of an alternative way of life; the Farm’s midwives have delivered 1,250 babies by natural childbirth, for Farm members and others; and an international relief project called Plenty has gotten its start on the Farm.

The Farm has also paid its dues. There have been hard winters, a hepatitis summer, and a bust for growing pot, for which Gaskin and others spent a year in jail. The community has evolved spiritually, culturally, and technologically — from tents and oil lamps to computers and solar panels.

When I arrived for this interview, I expected to see more or less the same Farm I’d seen when I’d last been there in 1980, five years earlier. From the minute I arrived at the gatehouse, however, I could sense something was different. For starters, I was the only visitor. Before, I had seen throngs of curious sightseers, veteran pilgrims, and hippie children along the road; now there was only the sound of my car engine. The fields that usually would have been plowed up for spring planting were idle, full of grass and wildflowers. The canning-and-freezing building, the radio station, the community kitchen, and the huge tractor barn were all vacant and boarded up. The Farm looked more like a ghost town than it did the busy community I had previously seen. Some of the houses I had helped work on during past visits were now empty, many with windows broken; others had been torn down. The children I saw were not tie-dyed replicas of their parents but wore designer jeans and jogging shoes. Their hair was cut shorter, and video games had their interest. In short, they seemed a lot like ordinary middle-class kids, except more mature, self-confident, and likable.

As I talked with a few of the members, I kept hearing phrases like “before the change” and “the new system.” Gradually I began to piece together what had happened: The Farm’s only substantial source of income had been the construction crew, which did outside work, and when interest rates had gone way up, business had begun to slump, and the burden of providing for the whole community had become too great. For a while the Farm had been in danger of having to sell off part of its land to survive.

Besides changes in the economy, there were internal tensions. Many Farm residents felt they weren’t accomplishing anything, or that the standard of living was too low, or that they were being treated unfairly. Other families, now in their midthirties, were growing tired of living with dozens of people and wanted a more traditional nuclear-family structure.

After selling their soy-foods company, Farm Foods, to pay off their land mortgage, the board voted to change the basic financial structure of the Farm; total collectivism had become economic suicide. Now each family had to earn its own income and pay a weekly tax that went to support the few remaining services, such as the school. But many families were unable to find outside jobs, and others disagreed politically with the changes. People began leaving, and the Farm’s population dropped steadily from fifteen hundred to the present three hundred adults and children.

The last time I had sat at Sunday Morning Service, there had been a meadow full of people, and Gaskin had needed to use a microphone. On this Sunday morning we numbered fifteen and sat in a small circle, exchanging ideas. But the feeling I came away with was one of determination, not defeat. These were not starry-eyed hippies looking for a free ride but seasoned homesteaders. Most of them had arrived with the original caravan; they had seen many others come and go. They now viewed their practical knowledge as an untapped resource and were considering using the Farm as a conference site for community-training projects.

Gaskin is as hard to pin down as his community. Is he a leader? Although he shuns this label, he has been criticized for being too egocentric and demanding. Since he is the Farm’s founder, no one can dismiss his strong influence on internal affairs, yet the Farm has always been governed by an elected board that may or may not agree with him. Is he enlightened? Gaskin sees that as more of “a process, and the enlightened person can think an ordinary thought and be ordinary, or the ordinary person can think an enlightened thought and be enlightened. It depends on your contract with yourself. I made a contract with myself about a way I was going to be for the rest of my life, and I haven’t broken that contract.”

Is he controversial? Definitely. And he shows no signs of changing anytime soon.

Gaskin sees no distinction between spiritual practice and political action, and in the past he has aligned himself with the antinuclear movement and the issue of Native American land rights, often traveling around the country to speak on behalf of both. As the founder of Plenty, he has worked for peasant reforms in Central America, which earned him the first Right Livelihood Award, a sort of alternative Nobel Prize.

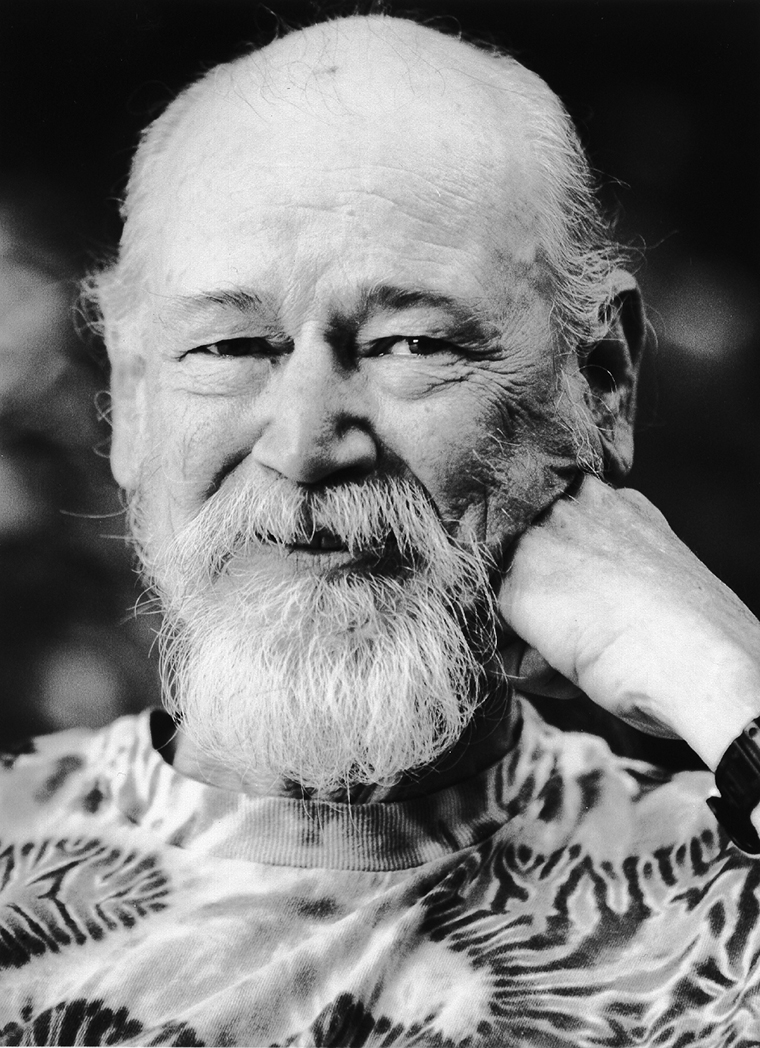

Though his waistline and hairline are beginning to reflect his age, he says he will always remain a hippie at heart. His face is more wrinkled, but his eyes still sparkle with a mixture of mischief and inner wisdom.

Gaskin wasn’t as eager to talk about metaphysics as he was about his family’s new cottage industry, The Practicing Midwife, a magazine begun by his wife, Ina May. [The magazine’s name was later changed to Birth Gazette. — Ed.] It deals with all facets of natural birthing, particularly the political issues, and its production has turned the upstairs of their home into a computerized beehive. Stephen was particularly proud to show me his latest personal project: installing their first indoor bathroom. He joked that “when it’s done, we’re going to celebrate by having a pot party.” Computers? Fancy indoor bathrooms? Could this be the same man who once stated that he “fought every inch of electrical wire that the Farm wanted to put up”? It simply reveals someone who has never been afraid of change, either personally or culturally. He seeks constantly to stay at the vanguard of his generation, yet always with integrity and a moral consistency that he traces all the way back to the spiritual truths he encountered on Haight Street in San Francisco.

[Those interested in learning more about the Farm, or Plenty, its international aid program, can visit thefarm.org.]

Stephen Gaskin, circa 2010

Thurman: What was your religious background?

Gaskin: Not much. American Christmas card. My mother was half agnostic, and my father wouldn’t talk about the subject at all. There was no pressure on me to be religious. I think that’s why it was so fresh to me and why it turned me on. I’ve always thought organized religions are a bore. They’re just absurd. What I have come to respect is the continuing, unending stream of people who have a spark or flash of enlightenment that changes their view so much they usually have to tell about it. They leave tracks, and you follow them like an explorer, knowing that there are other people who have been through these changes. And if you have the good luck to read good books, you find out that, as far back as we have records, people have had similar questions, concerns, problems, and flashes of enlightenment. So you find yourself in the mainstream of humankind.

Thurman: How was it that you began to fill the role of spiritual teacher?

Gaskin: I was about ten years older than most of the hippies. I had also been in the Marine Corps; I had been to Korea; I’d carried the dead and wounded. I couldn’t listen to any bullshit about military takeovers. Also, I was just coming into my own at that time and realizing that I had to get rid of the part of life that was just trimming. See, I believed, and I still believe, in our hippie realization of this cycle we’re in. And although it caused a lot of us to become interested in the Eastern religions, because they have such fascinating cosmologies and psychologies, I have always tried to keep faith with the fact that we had a realization that was precious and common to our generation. I don’t fit into any of those Eastern religions. I haven’t been to any swami school; no Zen master has given me any stripes.

Thurman: If you hadn’t become a teacher, what else might you have been?

Gaskin: Well, I don’t see the role of teacher as being mutually exclusive with everything else I want to accomplish. I am a nonviolent social revolutionary, and I think that anybody who follows religious disciplines ought to be one, too. And people who say they’re religious but aren’t social revolutionaries are fooling themselves, because if religion is to have any validity whatsoever, the gap between the real and the ideal cannot be so unbridgeable that it’s all pie in the sky. There’s got to be a chance for justice on earth.

I don’t fit into any of those Eastern religions. I haven’t been to any swami school; no Zen master has given me any stripes.

Thurman: What has happened to the enormous energy that was generated in the sixties?

Gaskin: Some of its seeds have fallen on stony ground, some of its seeds have been eaten by birds, and some have fallen in places where that energy has returned a hundredfold. That’s what happened to our revolution: it’s still here. Although there’s not a visible hippie tribe on the streets or roads or in the cities, as there used to be, it doesn’t matter, because we permeated the culture. The popular music of this country is now rock-and-roll. You hear people on Hee Haw talking hippie talk that was invented on Haight Street. They say, “Dig this.” Everybody does. We permeated the culture, and that’s what we were supposed to do.

The other thing, to me, is what I talked about earlier: not to forget that this was a homegrown set of realizations that hundreds of thousands of people had. I am acquainted with about half the Eastern religious teachers you hear about on the circuit. That’s all fine, but they didn’t bring those ideas to this country. Those ideas grew out of this soil like mushrooms, right out of the cultural conditions we’d gotten ourselves into.

Thurman: As a way of coping with, or changing, those conditions?

Gaskin: You’ve got to be a rich country to have hippies. They’re a free, privileged scholar class that can study what they want. They’re like young princelings. That’s why the only other places to have produced hippies are countries like Germany, because they’re rich enough. It’s really been an upscale movement, in a way, except for when it broke through. And when it broke through was when it was the most revolutionary and really scared the Establishment, because hippies bond across cultural, religious, and class lines. That’s terrifying to the Establishment. That tears down everything that they’ve stood for for five thousand years. The communists want their dynasties, too; everybody wants their dynasties. They don’t want people to be able to step out of one culture and into another. They can’t stand to have Ford heirs chanting, “Hare Krishna.” People who were supposed to have lived off the wealth of old Henry Ford going out and sitting cross-legged and wearing ponytails? It ain’t hardly civilized!

Thurman: Was some of that energy maybe too optimistic? Expecting something to happen too soon?

Gaskin: Things did happen: We got out of Vietnam. We made it so that you couldn’t run a racist society separate from the rest of the United States, so that the Constitution reached down into the far corners of Alabama and Mississippi. We got rid of a president who was a tyrant. We brought new forms of education to other countries through the Peace Corps. There was a tremendous cultural flowering that took place. All flowers eventually curl up, but the significance of the flower is in the seed. And the seeds were planted.

You could say we sent out a call. I guess I’m one of the guys designated to stay by the phone and answer the replies as they come back. I get letters from people who were babies when I was a hippie; who, now that they’ve grown up and looked at the world, say, “Oh, I wanted to be one of those. Are there any left? Is it too late? Did I miss it?” And I say, “No, it’s part of an ongoing thing, a cultural thread that should continue forever.” It helps keep societies from going crazy. Societies are too powerful by definition. Everybody has to be an anarchist to some degree. The amount of police power that governments are developing is terrifying. There always have to be people who, not from malice or greed or evil but for the best social reasons, remain outlaws.

Thurman: How hard has it been for you not to set yourself up as a guru figure? Is it tempting?

Gaskin: Not to me. Not the trappings. I might fall into excesses, but I’m too much of a down-home kind of person to get into ceremony and pomp. I was amused when I saw fifteen hundred hippies drag a huge chariot with [Hare Krishna founder] Bhaktivedanta on it through Golden Gate Park. I thought that was funny at the time, and I still do.

I think my temptations are different. When you’re in a position of having a lot of responsibility and can’t lay enough of it onto others, you tend to act fast. You shoot from the hip and are brusque because you’ve got so much weighing on you. You want to get everything over with quickly. It’s the same condition that doctors find themselves in. Because, to a doctor, you’re just one of a thousand appendectomies, but to you, this may be the only hospital trip you’ll ever have, and it’s a hell of a big deal. The doctor isn’t going to give your operation the level of importance you think he or she should. I can fall into that, and I have to be aware of it.

Thurman: So there will never be any Stephen Gaskin School of Meditation?

Gaskin: No. People have hung stuff like that on me, you know, but I haven’t liked it. And, in spite of what some have said, I don’t want it. The old religions are full of hierarchy. Maharishi Mahesh Yogi [founder of Transcendental Meditation], for instance, now gives initiations by videotape. That implies a great deal of hierarchy, if one guy’s blessing is so good that you can get it by tape instead of in person.

People have spoken about my “followers.” Well, I don’t have followers; I have friends.

Thurman: Is it necessary for a community to have a central figure or leader?

Gaskin: I don’t know if it is or not. There are millions of villages all over the world that don’t have one — although somebody usually seems to rise to the position of elder or something like that.

Thurman: How is the Farm different from some of the sixties cults that were established?

Gaskin: I remember a long time ago, when we were still on coal-oil light, seeing two paths: One of them went to a place where we became almost a quietist village, where all we did was polish our craft, do our meditation, and study our own thing. That looked like a dead end to me; it had no freedom in it, and we would become stagnant if we went that way. The other path was to grow, and to influence and interact with the world.

Thurman: What mistakes have been made by other communities that have failed?

Gaskin: I don’t think it’s a question of mistakes. “Mistakes” implies that you should have known something would happen. I think there are normal evolutions, and that if you enter into community without the awareness of those evolutions, you’ll evolve yourself out of being a community. In Israel they talk about the kibbutz [a collective farm] and the moshav. The moshav is like a kibbutz that has evolved away from collectivity and toward the families having more individual control of their money. I think we’ve become somewhat of a moshav.

Thurman: Let’s talk about the changes the Farm has been going through. When did they start happening?

Gaskin: I think our peak population was four or five years ago, with about fifteen hundred people on the property; there were some twelve hundred residents, and the rest were passing through, here to have a baby, study soy foods, and so on. The end of the Carter administration and the beginning of the Reagan administration were very hard on us. We had a 105-man construction crew, and when the prime interest rate went to 21 percent, nobody would build a doghouse. It just stopped us: imagine 105 jobs gone. We used to try to rotate the people who had to go off the Farm and work, but we didn’t really do that as much as we had intended, because the construction workers got to be journeymen in their craft and didn’t want to rotate. And they wanted to keep more of the money they made. So we hit a kind of plateau. We were an absolute collective on an honor system, which meant that the community coffers leaked like a sieve. People had checkbooks who had no reason to have them, and they were running funds out that somebody else was working by the hour to earn. We didn’t have enough accountability. We didn’t have enough skill in accounting, much less a philosophy of it.

Thurman: Were you overpopulated?

Gaskin: In the sense that we had too many people here who were not here for the community, yes. We had dedicated people, guys who had been carpenters for several years, who really wanted to be part of the Farm. They got burned out because there were day-trippers soaking up the funds.

The question of self-government is something we’ve worked on longer than almost anything else. I don’t know how many different kinds of boards and committees we’ve tried. They’d all lose their clout in about a year or two. They’d make a few moves, and then people would just quit listening to them.

The state requires us, as a nonprofit corporation, to have a board of directors. So finally we said, Let’s take that board of directors and make them the governors of the Farm, and they will be responsible to the state for making sure we are the type of nonprofit corporation we say we are — and that will put people’s tails on the line about maintaining the standards.

So we elected a nine-member board. And because of the kind of trouble we were in, the party that got the most seats was made up of business-minded guys who said, “We are sloppy; we have got to be accountable.” So we elected essentially a business board — I think seven out of nine. We got smarter about business, and things tightened up real fast, but there were side effects. Some people had to leave because they couldn’t earn as much as was required under the new system.

Thurman: You mentioned a two-party system on the Farm. How does that break down?

Gaskin: The Farm industries and businesses wanted to separate themselves from the community enough to have financial independence, like the moshav. So they bought the businesses from the Farm. For instance, the Farm owns only about 25 percent of Farm Foods right now. The employees and investors own the rest. So they are making more money than people here who are working by the hour at the trailer factory, for example. We’re beginning to have two social classes.

The other party is more the folks who are interested in living on the land, who are committed to the ideal of community. They want the Farm to become more of a conference center for the transmission of our learning.

Thurman: Your population is so much smaller now. Was there a mass exodus at one point?

Gaskin: It happened in waves. The ones who left ranged from folks who came here for a formal spiritual community, which we aren’t, to folks who thought they were going to get rich and have a swimming pool and live better than this, and finally they decided to go out and do it by themselves. People left for many different reasons. There are some out there who are my close friends who write me really lovely letters, and then there are folks out there who are mad at me and think I caused them to waste a couple of years of their lives.

Thurman: So there were bad feelings?

Gaskin: It was like a divorce. There were folks who had been here for years who, others felt, had contributed nothing and should be on their way. And there were people who felt they had contributed a lot and so should get a bunch back when they left. Our board members are confronting all those problems and trying to solve them in the fairest ways we know. The nucleus of people who are here now are pretty sure we want to stay here. If we didn’t do this, we’d probably start something new somewhere else, and if that’s the case, why not continue with this?

Thurman: Did it look as if the Farm might fold at one point?

Gaskin: It was scary for a while when we were counting noses to find out if there was going to be a skeleton crew left who wanted to keep doing it.

It’s interesting that, after we started having television during Watergate, the kids began seeing commercials and began caring how they looked, wanting to look the way kids looked on TV. So some people who, for themselves, would live with long hair, bluejeans, and outhouses, for their kids had to provide beauty-parlor hairdos and designer jeans — because they felt that they weren’t being good parents if they didn’t give their kids all of that, although they had given it up themselves.

At first I took very seriously a lot of the shenanigans that went down here, much more than I needed to. Then I saw that you can’t stand in the way of a cultural movement and mass generational changes.

Thurman: Were people overly optimistic that the Farm would continue in the same way that it had — as a collective — indefinitely?

Gaskin: Those of us who are seriously committed to living in community wanted it to continue, but there’s no sense in being collective out of principle if it’s not working. So what we’re doing now is reassessing what we do want to be collective about. I don’t want to be part of anything that’s so institutionalized that you spend more time being mad at the institution than being helped by it.

Thurman: What do you see as the importance of the Farm?

Gaskin: There have been around four thousand residents of the Farm over the years, and the vast majority of those people are pacifists who are conscientious about what they eat and who care about what’s going on in the Third World and other cultures. Very few of those people turned out to be Republican congressmen. Most of them are still pretty idealistic folks.

We really helped the soy industry get off the ground in the United States. At one time our tempeh shop supplied the spores to all the other shops in the country. We had been living on soybeans for years by the time other people began experimenting with it to find out if it was cool or not. I feel we have helped out the movement all the way along the line.

There’s no such thing as a free lunch. A lot of folks worked real hard, which allowed others to have a free experience here. So now the experience is going to cost a little bit, and we’ll try to be as sweet as we can about it.

Thurman: What type of economic system does the Farm currently have?

Gaskin: We’re more of a cooperative, whereas before we were a collective. The main difference is that all our money used to be handled centrally. Now everybody earns their own money.

Thurman: So you could have some people on the Farm making more than others.

Gaskin: We already have that. We have some people who have a hard time paying the community taxes we have to pay right now, and for others it’s not a burden.

Thurman: How is that going to change the fabric of the Farm?

Gaskin: Hopefully we’ll raise the standard across the board to where those inequities are not so obvious. But I’m not going to begrudge my friend Bernie the right to drive a new car just because my car is fourteen years old.

Thurman: Would you say that in the past you weren’t choosy enough about whom you allowed to come live here, and that now you’re tightening up on that more?

Gaskin: No, I couldn’t say that, although at one point we had people who were coming here just because they were in love with the idea of us. They did not seriously understand what it took to keep the idea going.

Thurman: They were looking for paradise?

Gaskin: Yeah. And there were other people who knew that they were putting in more than they were getting back. It’s OK to choose to put in more than you’re getting back for the purpose of doing a good thing, but to fall into it because other people don’t pay attention makes you mad after a while, and some folks got mad.

The mistake that we made — and that, I think, a lot of people make — was estimating our income by taking the number of people in the community and multiplying it by the amount of money that each could make if he or she had a job, because it’s never going to work that way. There are always going to be people who are going to get sick or something like that. We never made anywhere near the amount of money we had projected.

Some of the folks who didn’t deserve to get hurt by the change of systems got hurt by it. They were working at what we call “public works,” like farming, sanitation, teaching, and medical services. Those people no longer had a way to make a living. They were never trying to make a living. They were trying to serve the Farm. A lot of them had to leave.

Thurman: Now that the Farm is getting more practical, is there a danger of losing your spiritual perspective?

Gaskin: There’s always a danger of losing the spiritual, but one great blessing to the Farm is that we are host to Plenty International, an overseas-aid group that has already spawned another organization larger than itself in Canada. That helps us to keep things in perspective.

Thurman: You used to not be involved in Tennessee politics, but lately that has changed. Can you talk about that?

Gaskin: At first we didn’t want to upset the local balance of power, but now we have two members on the county council. And we seriously helped put our congressman in office by producing a computerized mailing list for him. A week after the election, the local news said that one of the best-kept secrets in the race was Congressman Bart Gordon’s computer crew from the Farm. And those guys got an offer to go to D.C. and be on his staff, too!

Thurman: What changed your attitudes about local politics?

Gaskin: When we first came here, all the people who were running things were in their fifties and sixties. We were the kids, and we asked for sanctuary from the older folks. It was very kind and good of them to give it to us. That’s one of the reasons we have such a strong love of the local Tennessee people: we feel as if they gave us sanctuary here. And then the older folks died off, and the baby boomers are now in charge. So we get to be part of the action. When we had our first election, it wasn’t us against the Tennesseans; it was us and one wing of the Democrats against the other wing.

Thurman: Personally, how has your life here changed?

Gaskin: I get to do more of what I want to do now.

Thurman: What do you do less of?

Gaskin: Stand around and jawbone with people. I love people. I’m a very gregarious dude, and I can rap and rap. But I really like having the chance now to clean up my yard to the point where I won’t be ashamed of it whenever my father comes to see me. And having the time to complete some of my projects here at home. This bathroom project is significant. I’m really interested in people taking care of problems themselves and letting me off the hook so that I don’t have to take the blame for everything that happens around here.

People who say they’re religious but aren’t social revolutionaries are fooling themselves, because if religion is to have any validity whatsoever, the gap between the real and the ideal cannot be so unbridgeable that it’s all pie in the sky. There’s got to be a chance for justice on earth.

Thurman: You’ve caught a lot of criticism from the feminist movement about the more traditional male and female roles on the Farm. Has that been justified to some degree?

Gaskin: I haven’t felt confident enough for several years now to have any opinions about what women ought to do. As a wild, free hippie who had all his social mores get blown to hell by a couple of hundred acid trips, and then grew them back from civilization over the next decade or so, I can’t defend all the places I’ve been, other than to say, “Yeah, wasn’t that a trip?” But I would like it to be known that, for instance, pornography causes violence against women, and I am disgusted by portrayals of women in subordinate/slave/bondage roles. I have daughters, and I would be revolted if someone wanted to treat them in that fashion. I am also the general manager of Ina May’s Practicing Midwife magazine, which is a feminist cause. And there have always been women involved with management on the Farm. When we suddenly had the question put to us of how to make a living here, in some of our families the man got a job, and in other families the woman got a job. And whoever stayed at home helped take care of business, because it made the whole thing work. And I respect that.

Thurman: Let’s talk about Plenty. How did it get started?

Gaskin: Our first operation was to send fifty thousand bushels of grain to Spanish Honduras after a hurricane took out crops there. We also did some local tornado relief in Memphis in 1974. We were already an established aid organization by the time of the earthquake in Guatemala. Plenty was the Farm’s response to the question of whether or not we were going to be a quietist community. We said, No, we’re going to build an arm that reaches out to other folks.

I used to travel on the dollar’s favorable exchange rate. I would go to a poor country and live a long time on not much money. Now I feel that’s immoral. We wanted to find a way that we could go to those same countries with good karma, meet the people, and come in as helpers instead of as tourists.

We’re becoming so bland now, and I really pray that we get to see another burst of energy. When the sixties happened, it lifted me up and blew my mind and informed my consciousness in a way that was a million times heavier and more interesting than anything I’d experienced before.

Thurman: Plenty is the only project for which you’ve ever asked donations. Why is that?

Gaskin: Because I thought asking for money to support the Farm itself was wrong. I was trying to teach that the day of the begging monk is over, that a monk ought to pull his weight if he wants to help the world. A monk these days should have a job.

Thurman: What kinds of things does Plenty do that were not being done?

Gaskin: The concept of foreign aid prior to us was to do big projects. An aid organization did a $200 million railroad project in some African country, and when the guys who built the railroad went back home, the whole thing collapsed. And they built big, Canadian-style wheat farms in Africa, but the problem was you needed to have Canadian-style farmers to run them, too. So now the people who study aid groups are saying that grassroots assistance — building from the ground up, helping the peasantry get stronger — helps the whole country. And our kind of aid is becoming more relevant. In Guatemala we’ve put in twenty-seven miles of water pipeline. After the earthquake, in concert with other groups, we constructed a prefab-house factory that built twelve hundred houses, as well as rebuilding twelve schools. We’ve done soy-foods projects, reintroducing seeds and beans that are indigenous to each country. We now have two hundred farmers growing soybeans in Guatemala, and about one thousand families using a soy dairy there.

Thurman: How many countries have you done aid work in?

Gaskin: We had a crew of four in Bangladesh for a while. We’ve got people working on a soy dairy in Sri Lanka. In the Caribbean we’ve been to St. Lucia, Jamaica, St. Vincent, Dominica, and Antigua. We’ve been to Haiti, and we want to do an ongoing project there, but it’s hard to make it happen because Baby Doc [Duvalier, former Haitian president] still rules the roost. Plenty is also interested in Grenada, and we’re currently negotiating with the Mexican government to see what we can do for them.

We’re interested in developing businesses at a grassroots level, because these peasants don’t even have a mom-and-pop grocery store. We make a distinction between rank capitalism and the petite bourgeoisie. Small business is a good thing for the world. A lot of these businesses together form a thick web that makes for a good civilization. If you haven’t got much small-scale capitalism going on, then you’ve got multinational corporations and slaves. We don’t buy slaves anymore in this country — we just rent them.

Thurman: So you’re promoting self-sufficiency in these countries?

Gaskin: Exactly. We don’t want them to rely on us. And if the people there would like to set up a collective to receive the goods we give them, that’s fine, but we don’t demand it. We don’t care if somebody makes some money on a project we set up, because we figure that any cash flow has got to help a poor country.

Thurman: The more I look at the culture these days, the more it looks like the fifties all over again. Do you feel we’re headed for another sixties-type upheaval within the next decade?

Gaskin: Yeah, we’re getting nostalgic for the action that we used to have. We’re becoming so bland now, and I really pray that we get to see another burst of energy. When the sixties happened, it lifted me up and blew my mind and informed my consciousness in a way that was a million times heavier and more interesting than anything I’d experienced before. I think it did that for many people. And now, knowing that such a thing can happen, I can just sit here and wait for it — like “Yeah, here it comes again!”

I believe that it is cyclic, and I think the reason that [President Ronald] Reagan is getting such good play right now is that we were a little extreme in the sixties, and now we’re being paid back for fucking in the streets. Next time, I’m not interested as much in that as I am in making real, solid social changes that last for decades.