Singer-songwriter Ani DiFranco doesn’t like her music to be labeled. Some have called it “folk-punk,” but when asked to define what she does, DiFranco says, “I play music with a story.” Onstage she is mischievous and energetic, interacting with her bassist and drummer, asking the audience questions, bemoaning the latest headlines, and inviting the crowd closer (often to the consternation of security guards). She’s never had anything like a pop hit, but her audiences sing along with every song. DiFranco’s guitar playing is an aggressive combination of flamenco, country blues, and folk strumming. Her lyrics come in torrents and typically combine autobiography, politics, and punchy aphorisms. “My IQ,” for example, from her fourth album, Puddle Dive, includes a recollection of her first menses at thirteen and ends with the line “Every tool is a weapon / If you hold it right.”

DiFranco was born in 1970 in Buffalo, New York, to parents who’d met as students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). As a child she lived a precociously independent life, leaving home at the age of fifteen and earning money playing popular songs on the sidewalk for tips and spare change. She soon began to write her own material and at eighteen moved to New York City, where she found mentors in her teachers at the New School for Social Research and in musicians on the folk-music scene, including the late Pete Seeger. Like Seeger, DiFranco believes that music is best shared through live performance. At her concerts political passion and intense emotion are felt by both performer and audience. “It’s magic what music can do,” she says. “It has the ability to lift every single veil between you and someone else. Music is a social act — the language of the human soul that everyone understands.”

Now forty-five and living in New Orleans, DiFranco continues to be celebrated as a songwriter, poet, guitarist, feminist, and activist. Since her debut LP in 1990, she has released more than twenty albums on her own independent label, Righteous Babe, and has sold more than 4 million copies, but she remains ambivalent about fame and success. When she says the words “my career,” you can hear the quotes around them. In addition to her recordings, she lends her talents to benefit concerts, rallies, and humanitarian causes, including the Southern Center for Human Rights and the Roots of Music program, which provides free music education and mentoring to New Orleans schoolchildren. She’s been given awards by the National Organization for Women, Planned Parenthood, and several LGBT organizations. She’s also been accused of betraying her fellow progressives on occasion; she says the criticism from other women hurts the most, but it’s the price of being so open and autobiographical in her work.

I met DiFranco in the New Orleans house she shares with her husband, producer Mike Napolitano, their eight-year-old daughter, Petah, their two-year-old son, Dante, and the family’s new Mexican hairless puppy. (“My first dog,” she says. “The kids insisted.”) As any parent might expect, having children has changed how DiFranco spends her days and leaves her less time to write new songs. After two conversations at her home, we met for a third at a venerable local bar, where she was attending an informal meeting of the Roots of Music board of directors. DiFranco had ridden her bike to this rare evening without the kids. When she ordered a piña colada, she grinned and said, “Mommy’s night out.”

Leviton: By the age of fifteen, you were living on your own. You write, of that time, “She never had much of a chance / Born into a family built like an avalanche.”

DiFranco: Yes, it was all downhill. When I was small, my parents both had good jobs, but that financial security dissolved over the course of my childhood. My brother and I were both sensitive kids caught in a volatile situation. Our parents divorced when I was nine, and I lived with my mother for a while; then she moved to rural Connecticut when I was fifteen. The stress of her job as an architect was too much, so she quit and became a house cleaner to simplify her life. By that time I’d met some guys at the guitar shop, and we had a trio. So I told my mother I was going to stay in Buffalo.

My father was still living in the home where I’d grown up, but he and I didn’t have much of a bond, so I rented a room in someone’s house. I got kicked out of that living arrangement and spent my sixteenth birthday sleeping in a bus station. My childhood had prepared me to be self-sufficient, though, because my parents were often busy dealing with other problems. There were laws, of course, against a sixteen-year-old living on her own, but I remembered this Rastafarian who ran an apartment building, and I promised him that I was very responsible and wouldn’t tell anyone about our arrangement. So I had my own apartment. I started playing music anywhere I could, including bars. I wasn’t supposed to be there, but I made agreements with the bar owners that I wouldn’t drink. I was there for one reason only: to vent my spleen on unsuspecting revelers through my music.

Leviton: Wasn’t that a dangerous situation for you to be in?

DiFranco: Yes, and only when I got out of it did I realize how dangerous. Being a very young woman in a world of men, I was aware that I had to look alive. I had long hair and was semicute and sixteen and hanging out in a bar, so I got a lot of rides. I got whatever I needed. Then, when I was eighteen, whoosh! I shaved my head and put on combat boots. I was done with those gender games, with using that currency I had as a young female.

I moved to New York City and cried a lot for the first few months. This was in 1989, and homelessness and poverty were huge problems in the city. I had to step over people as I walked down the street. I was a sensitive creature, and the tough way New Yorkers interacted with each other was a shock. To meet it, I had to step up my don’t-fuck-with-me attitude. I was determined to make my own way, not to take favors from anyone. If I had to sleep in the bus station, I slept in the bus station. My ability to say no to people’s offers of help meant that no one had power over me.

Leviton: You’ve written that “art is activism.” Do you think all art is political?

DiFranco: No, but all art is hopefully about telling the truth of your experience. Even if you’re playing a role, you project the reality of your life through that character. It’s important that we artists tell the truth about ourselves, that we be open and vulnerable, because it makes the audience feel respected and less alone. One of my folksinging mentors, Utah Phillips, used to say his job was “exposing himself” to strangers.

Back in the day I would lock eyes with people in the audience and really be there with them. It was physically and emotionally exhausting. After a show I would stay up all night obsessing over the quality of that interaction. I never thought I’d done it well enough. I was always trying to improve: How could I say exactly the right words to open somebody up to a new idea? How could I open myself up to other people?

Then, when my career started to pick up in the mid-nineties, the media became part of that cycle of judgment. I realized that if I was going to be of any good to anyone, I needed to tune it all out. I needed to stop reacting to the reactions to my work.

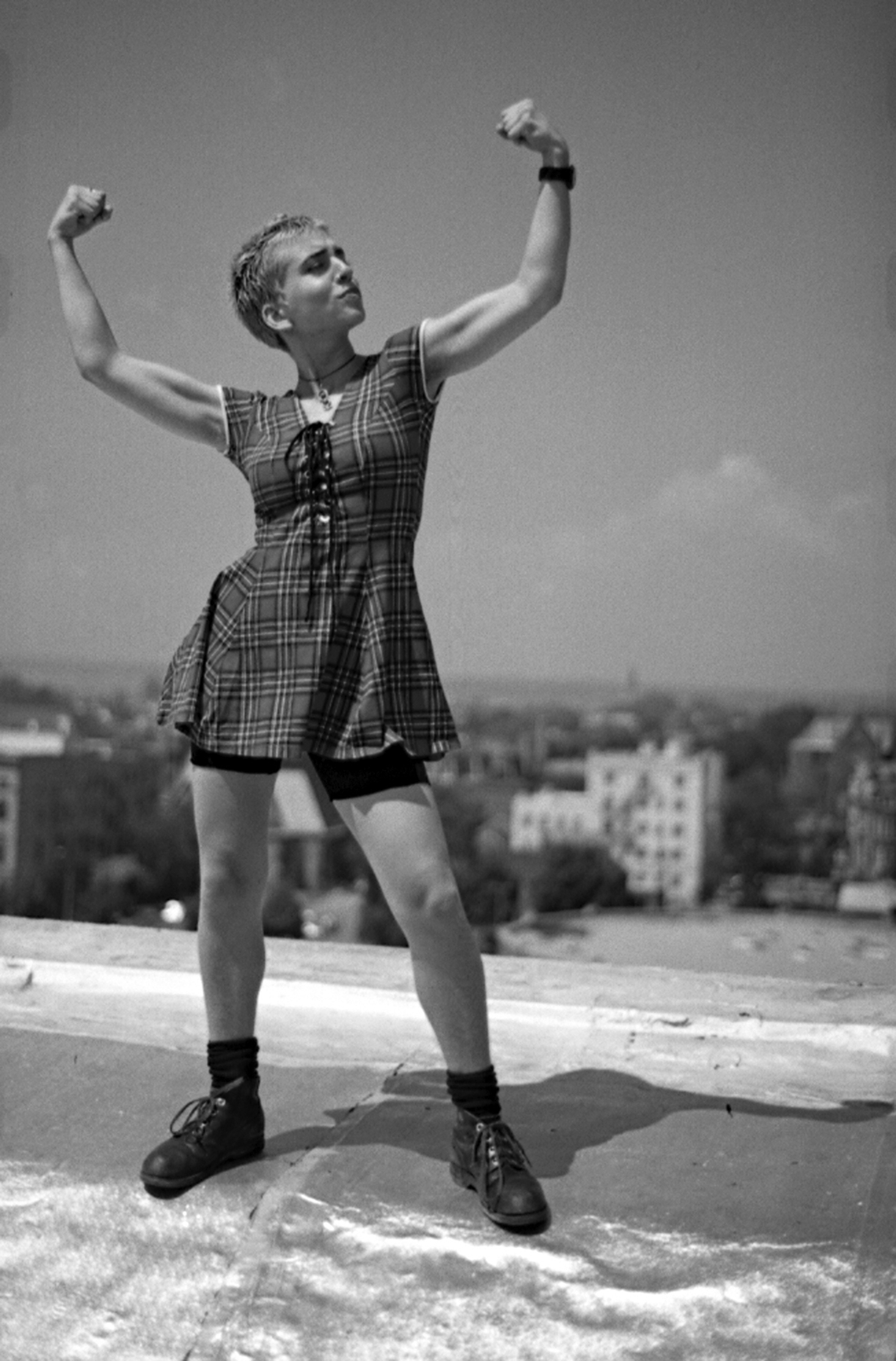

Leviton: At nineteen you started your own label, Righteous Babe Records, with your friend and manager, Scot Fisher. The logo — based on a photo of you in a bodybuilder pose with both arms cocked and your hands in fists — reminds me of Rosie the Riveter.

DiFranco: Scot took that picture up on the roof of the Sidway Building in Buffalo, where the label’s original office was. We were a mom-and-pop operation: Scot was the photographer and the dude who answered the phone, and I was the graphic designer who would paint the album covers. The pose was instinctual. It just felt right to me, like [roars]: Look out!

It’s funny you bring up the logo, because the other day Anna at the Righteous Babe office sent me a post from Facebook, an anecdote from the mother of a three-year-old girl: The mother had on a Righteous Babe sweatshirt, and her little girl pointed to the logo and asked, “Mommy, is that a girl?” She said yes, and her daughter asked, “Is she so, so, so strong?” And her mother answered, “Yes, she is so, so, so strong.” And her daughter said, “That makes me happy, Mommy!”

It’s amazing that even a logo can do good work in the world. You never know what part of what you’re doing or saying is going to reach someone else.

I originally called the label simply Righteous Records, because I felt I was on a righteous mission to uplift people. I was intentionally putting myself in that religious context: this, too, was God’s work. Then I got a letter from a gospel label with that name in Oklahoma. So I changed it to Righteous Babe, which was an inside joke: As young women, my friend Susie and I would get catcalls on the street — “Hey, babe, want a ride?” — and we started calling each other “babe,” imitating the catcallers, taking back that word. It was a better name anyway.

Leviton: Did you try to construct a business model that wasn’t capitalist?

DiFranco: Yes, but over the years I’ll admit there have been compromises. In the beginning I refused to sell anything except records. I was a musician, and my product was music. Period. I believed music was fundamentally a social act. Even putting it on tape or vinyl kind of skeezed me out. No way would I ever sell T-shirts.

And then, in the late nineties, I became so overwhelmed I was going to quit. I was traveling by myself on tour to save money, and I had to deal with a new sound guy every night. You can imagine the amount of attitude I encountered. There I was, a lone woman with a shaved head and an acoustic guitar, telling the sound guy to take away all the high end and crank the low, because I wanted my guitar to sound like a fucking truck coming at the audience. Night after night they wouldn’t do it. Scot finally put it to me straight: if I wanted to travel with my own sound guy, I had to sell T-shirts. He convinced me that my message could be represented on a shirt. It didn’t have to be crass capitalism. It could be meaningful.

The first T-shirts had no images of me, just song lyrics. I compromised some over the years, and now I sell a limited variety of clothing, posters, guitar picks, and so on. Righteous Babe Records grew big enough to start supporting other artists and releasing their albums alongside mine. But right now money is tight, and we’re not able to provide as many benefits to the people who work at the label as we used to. Even my own healthcare coverage has gone way down. I could allow my music to be used in advertisements and make some money. That would certainly let me stay home with my kids a little more. But that’s where I draw the line. That’s where I’m going to die: no ads.

I was determined to make my own way, not to take favors from anyone. If I had to sleep in the bus station, I slept in the bus station. My ability to say no to people’s offers of help meant that no one had power over me.

Leviton: You have written more than a few songs criticizing the music business. In “The Next Big Thing” you tell a music executive, “Thank you for your interest / But my ‘thing’ is already just the right size.”

DiFranco: The more successful I became, the more people wanted to partner with me, make me even bigger. The people who approached me were not bad people; they just weren’t in line with my mission. I knew that if I partnered with them, my focus would be diluted.

Leviton: Weren’t you interested in reaching the largest-possible audience?

DiFranco: No, I wasn’t. And I had to ask myself every day, Why not? There were many years when I’d be playing in a club for fifty people and some songwriter would open for me, and the next year I’d be playing that same club for a hundred people, and that songwriter would be on the cover of music magazines. All those songs I wrote about the business I wrote to myself, to remind myself I don’t need to go that far, that fast. If I went for the magazine covers, something essential would be lost. I needed to be reminded of that, because it was hard not to chase the carrot.

It helped that I found playing for a handful of people truly inspiring. If those five people are really present, and I’m really connecting with them, that’s as rewarding to me as playing for five hundred. In fact, when my crowds got too big, it was less rewarding. At the peak of my career, I’d play for nine or ten thousand people at once. Imagine trying to lock eyes and make a personal connection with ten thousand people. It doesn’t happen. My anxiety level was high, because I did not have a sound appropriate for those huge spaces. I was trying to do something subtle, and it wasn’t working there.

Leviton: For your fans the energy you shared in concert generated a sense of connection to the point that some people began to feel a kind of ownership over you.

DiFranco: Yes, but that connection was feeding me, too. We were all desperate for something. I’ve been touring for twenty-five years, and many people who come to my concerts today have been on that journey with me. I have a more tender relationship with my audience now. It’s less frantic. There are more knowing nods. I take a gentler approach, with less of that aggressive eye contact. I don’t mean to be any less engaging, but I’ve learned that sometimes — even with people who are resistant to you, who don’t like you — if you wait long enough, they will show you their good side.

Leviton: Early on you were writing intense, autobiographical songs like “32 Flavors,” with the lyrics “God help you if you are an ugly girl / ’Course too pretty is also your doom / Cuz everyone harbors a secret hatred / For the prettiest girl in the room.”

DiFranco: I was expressing a desire for kinship with other women instead of competition. I wanted to be part of a supportive community. It’s a feminist’s kind of longing, not to always be fighting to be on top. We’re a web, not a totem pole.

At first I was afraid to write about my own experiences. I worried what other people would think of me. But then listeners began cheering me on, saying, “Yes, I have that problem, too!” I realized that my job was to be as honest as I could about my experience. And I’ve done that. I’ve also taken certain artistic license for political purposes. For example, in “Shameless” I sing, “I gotta cover my butt cuz I covet / Another man’s wife.” It was really a man I was interested in, but I changed the gender. I put my bisexuality into my music because I wanted bisexuality to be a part of the songs and stories in the culture.

Leviton: Were there any subjects you wouldn’t write about?

DiFranco: Abortion was hard to tackle. I understood that the antichoice people were trying to control women, but I also lived in this country, and I was ashamed to admit that I’d had an abortion at eighteen and another at twenty. What changed me was reading “the lost baby poem,” by Lucille Clifton, the African American feminist poet and a fellow Buffalo native. Her work inspired a song about my abortion, “Lost Woman Song,” which was on my first album in 1990. So I faced that fear pretty early on.

Leviton: Now that you have kids, do you look back on your abortions differently?

DiFranco: No. At the time it was clear to me that having a child would have been a very bad idea, and it’s still clear to me today. That would have been an unhappy child with an unhappy mother; we both would have been damaged. Going to Women’s Services in Buffalo was a difficult, sad, somewhat painful experience. Antichoice activists held up gory pictures and screamed in my face as I walked in. None of that made me any less sure of my decision, but afterward I thought I should have felt more guilty, should have mourned more. I certainly don’t think that now.

I became a magnet for young women who’d made similar choices and needed to hear those choices affirmed by the culture. They were looking for acceptance. Every time I had the courage to open up and reveal difficult truths, there was immense gratitude for it.

Leviton: How did people react when you first performed “Lost Woman Song”?

DiFranco: I became a magnet for young women who’d made similar choices and needed to hear those choices affirmed by the culture. They were looking for acceptance. Every time I had the courage to open up and reveal difficult truths, there was immense gratitude for it. Of course, there was also criticism. I did encounter fear and resentment from some men. I was called a “man hater” many times for expressing some female anger. For several years I was synonymous with hairy, angry, humorless feminists. It was a box I had to slowly fight my way out of. But it never meant as much to me emotionally as the gratitude did.

Leviton: When you wrote explicitly about sexuality, did you hold anything back?

DiFranco: In hindsight I can see there’s a lot I left out. I was focused on certain aspects of sexuality, such as trying to negotiate monogamy when that was not my body’s instinct. Monogamy is not a natural law. I was struggling with the culture’s expectation that when you sleep with someone, it’s like they own you, unless you’re active in counteracting that assumption.

If you want to go against the unwritten rules, you have to be confident. I didn’t always have that confidence. So I lied and hid. I grappled with fidelity and monogamy even as a mature adult. I remember meeting someone in New Orleans, a terrific musician, and one of us followed the other home, and he told me he was very promiscuous — and I thought, I’m going to use that line in a song. The lyrics for “Promiscuity” started there: “Promiscuity is nothing more than traveling.”

I think what I’ve been saying in my songs all these years is: respect yourself; listen to yourself; you are not crazy. This turned out to be an important message for other political radicals and for women in general. We internalize the culture and underestimate our own power. It’s easy, for women especially, just to plug along and feel conflicted and incapable and alienated. But once you begin to recognize your own truths, then you can find words to speak them. And once you speak, you find that you are not alone. All it takes is for one person to come out and say, “Me, too,” and then bingo! The alienation is gone. But you have to practice tuning out the noise of the culture to hear the messages transmitted from your gut and your heart. You have to become like a bird-watcher and be vigilant and develop the skills to spot and name the quick flash of awareness in yourself. When nobody else seems to have seen what you saw, you have to be able to say with confidence, “That was a scarlet tanager. I know it!”

Ani DiFranco on a roof in Buffalo, New York, 1990.

© Scot Fisher

Leviton: I first saw you live in 1996. I enjoyed your performance, but it was also a strange experience for me. I’d brought my fifteen-year-old son, and we were surrounded by teenage girls and lesbian couples who knew the words to every song. It was like we’d wandered into a tribal gathering, and it wasn’t our tribe.

DiFranco: In my aggressive early days the people who showed up at my concerts were mostly feminists. I started out in life as my mother’s daughter, and I’m only just now discovering how much of my father is in me. He was a live-and-let-live person. I didn’t connect to that when I was a kid; my mother’s energy was much more striking. I identified with her feminist struggles as a female architecture student at MIT. She was a driven and trailblazing woman. And she also did all the cooking and cleaning at home — until one day, when I was nine years old, something in her snapped, and she put a sticker on the front door that read: THESE PREMISES ARE NO LONGER UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF THE HOUSEWIFE SYSTEM. Basically she quit and told us to deal with it. So I started doing the cooking.

For a long time my life mirrored my mother’s journey of emancipation, but now I’ve come through the other side feeling free to be more like my father.

Leviton: When you were playing in bars in your teens and using your youth and looks and talent to get what you needed, were you aware of feminist critiques of the culture?

DiFranco: Not in Buffalo. When I got to New York City at eighteen, I was working in kitchens while I took my demo tapes around to clubs to get gigs. One day I was walking down 13th Street and saw the New School for Social Research. I liked seeing those words together — new, social, research — so I walked in and signed up for classes. I was lucky to get a reasonable student loan, unlike nowadays, when a student loan is a type of indentured servitude. And I took Feminism 101 and creative writing from poet Sekou Sundiata, who became one of my mentors.

The New School offered courses like Marine Biology: A Marxist Perspective. [Laughs.] I took a class on the life of Malcolm X as seen through Joseph Campbell’s concept of the hero’s journey. The white kids in that class sat on one side of the room, and the black kids sat on the other side, and we yelled at each other. I learned that you could have a passionate, personal debate with people and then go hang out in the student union with them afterward. That has been mostly lost in our culture of outrage, where you can’t even speak for fear you might say the wrong thing and become a pariah. But you have to be willing to say the wrong thing if you want to get through political deadlocks.

My racial consciousness was transformed at the New School. I remember how Sekou would sit at the front of the class and let people vent all this racial tension at each other, and then he would just drop a question on the group and make everyone stop and breathe. He had real grace as a teacher. He was an Afrocentric New York poet who performed his work with a funk band. I was captivated by his explorations of the rhythm of language and his way of promoting social justice through his art. He taught me that you do your work every day. Like Utah Phillips would say, quoting the great Catholic Worker anarchist and pacifist Ammon Hennacy, “My body is my ballot.” I vote with my body every day, all day long.

Leviton: You learned a lot from Utah Phillips and Pete Seeger and other members of the folk community and the Old Left. How did you first encounter them?

DiFranco: I met them at folk festivals and benefit concerts. There was a fair amount of resistance to me in the world of traditional folk when I came in with my different sound and different look, but the people who counted — Utah, Pete, Tom Paxton, Peter Yarrow — were grateful that somebody young was showing up and bringing other young people into the mix.

I think I first met Pete Seeger at the Clearwater Festival, which he founded to raise funds to clean up the Hudson River. Each time I saw him was a lesson in how to be a better person. At one of the many benefits where we both played, there was a lot of posturing among the performers, and Pete just came in and transformed the mood. He had everyone sing a song together before the show, to remind us all why we were there. At his ninetieth-birthday party in 2009 I watched him do press conferences all day long. An interviewer listed Pete’s many awards and honors and then asked what was his greatest accomplishment. Pete said it was marrying the best woman he’d ever met, staying married for seventy years, and having three kids and six grandchildren. In other words, he said a successful human being is someone who’s created a happy family and supportive relationships. He approached the world with that kind of energy.

Leviton: You looked up to older artists like Pete and Utah when you were coming up. Is there a crop of young singer-songwriters who look to you as a model in the same way? What advice would you give them?

DiFranco: I’ve supported and mentored many young artists, and Righteous Babe has been a home, or at least a halfway house, to some of them. In terms of advice: I never tell people what to do in their art. If I like you, my attitude is “I like everything about you, especially your flaws.” But if I had to give advice, I would tell them to focus on getting the next gig, and the next, and the next. Once you start connecting with audiences, the rest of the puzzle will fall into place. But you have to be patient while you develop the skills and put in the time to make that connection. And if a career in music isn’t sustainable, at least you will have skills that can be applied in other areas.

Speaking of careers in music, you know what I really long to see? More women and people of color working on the production end of the business. Roadies and sound engineers and guitar techs and stagehands are in sore need of diversification. I mean, no offense to white dudes. I love my white dudes! But seriously: Calling all nonwhite dudes and women! Please start apprenticing with a sound engineer or guitar tech now.

Leviton: You’ve said that live performance is your primary art form; you prefer to have a direct, one-on-one relationship with your audience. Is that changing now that you’re a parent of two? Are recordings becoming of higher importance?

DiFranco: Not really. My kids have made my records better by slowing down my process, but live music will always be at the center for me. All of my best teachers have been extraordinary live performers. I feel a kinship to jazz musicians and stand-up comedians: the stage is the laboratory where we do social experiments and make discoveries. It’s where everything radical and intrepid and vital in our art takes place.

Leviton: What challenges do young artists today face that you didn’t?

DiFranco: One thing I would find daunting now is how fast everything happens. It’s hard to have the patience to master your art or build a career brick by brick when everyone expects results at the speed of the Internet. And when you’re trying to hone your craft, part of that process is making mistakes, and now those mistakes are all on display on YouTube or Twitter. Of course, the flip side of that are the massive opportunities for exposure that the Internet makes possible. The Internet is a powerful tool I never had in my early years, but in many ways I’m glad it was not there to exert its pressure on me.

For some people I was never a good lesbian, or a good bisexual. [Laughs.] I’m pretty much straight but adventurous. I sometimes have to defend my right to be a queer warrior and to be mostly heterosexual myself.

Leviton: In your songs you often avoid using gendered pronouns, so it’s not clear whether, for instance, you are admiring a male or a female body.

DiFranco: I do like the freedom of English. It’s not as gendered as the Romance languages. I can say “me” and “you” and leave the interpretation open to the listener. I often try to write in present tense and first person, because when you use third person, it’s less direct: you’re telling a story; you’re stepping back.

Leviton: But in a more recent song, “Emancipated Minor,” you sing, “Riding a Greyhound down to the city / With her fake ID.”

DiFranco: Yes, around the time I had my first baby, I did write a bunch of songs that look back on my life, reflecting on the person I used to be and how she came to be and disappeared and is being reborn.

Now I’m playing with point of view even more. In “Life Boat” I start with the line “Every time I open my mouth / I take off my clothes.” It sounds like a typical first-person lyric of mine. But as the song goes on, you discover that the speaker is a homeless woman who was unable to take care of her child. I’ve been going more in that direction, expanding the “me” in the songs, to the dismay of all the literal thinkers out there. One of my recent challenges to myself is to treat songwriting as more of a literary experiment, to use character and metaphor. For example, in “Allergic to Water” I sing, “It itches my throat and blisters my skin.” After the song came out, I received a letter of concern for my condition. [Laughs.]

Leviton: Are there other examples of songs you think the audience misinterpreted?

DiFranco: I don’t know that I’ve felt completely misunderstood, but I’ve often felt reduced. I might be singing a song that’s about many subjects, but people will react to one line and cheer for it every time. Meanwhile the rest of the song is going by. This used to happen a lot with “Not a Pretty Girl.” The first verse starts, “I am not a pretty girl,” and goes on to say that I’m no damsel in need of rescue, so “put me down punk.” By the end of that verse, all the girls in the audience would be screaming — and they would continue screaming right over the beginning of the second verse, which starts, “I am not an angry girl.” The irony always felt so thick. The song pivoted, and they missed it.

It’s partly the media-inspired preconceptions. People have been told ahead of time who I am and who my audience is. I have a friend named Randy who has been coming to my shows since 1990. He’s this husky biker type, and one time he sent me a picture of himself sitting in an empty theater holding a sign that read: HETEROSEXUAL ANI DIFRANCO FAN CLUB. I loved him for that.

Leviton: Some members of your audience seem to demand a kind of personal purity from you. Has that been difficult?

DiFranco: I’ve been hurt by it at times. Because I’m a “public person,” people often assume that everything I do is for the public. That couldn’t be farther from the truth. I’ve always been bad at sticking to a persona. I’m more random and impulsive.

At one time I was known for wearing a tank top and jeans onstage pretty much every night. I remember I walked out one evening in a dress, and a voice from the balcony screamed, “Sellout!” It just crushed me. I had to hide tears during the first song. Being cut down by a member of my own tribe is debilitating. But I put myself in the position to take that sort of heat. I mean, for some people I was never a good lesbian, or a good bisexual. [Laughs.] I’m pretty much straight but adventurous. I sometimes have to defend my right to be a queer warrior and to be mostly heterosexual myself.

Once I began performing outside the U.S., it was a completely different vibe. In Europe or Japan, where there wasn’t a huge media stereotype of me, people were reacting to all aspects of the music, not just the lyrics. Many different kinds of people would show up, and I thought, Holy shit, I’m a fully formed artist if I leave my country! In the U.S. the media preconceptions make it more difficult for the audience to see me as I am.

Leviton: In 1997 Ms. magazine picked you as one of its “21 feminists for the 21st century.” You circulated an open letter to Ms., objecting to how you were portrayed in the write-up. What did you object to?

DiFranco: I said I was flattered to be included, but the magazine focused on my financial success and the number of records I’d sold. Being recognized as some sort of business pioneer, after I’d spent ten years fighting capitalism, pissed me off. I thought Ms. was capable of moving away from the language of corporate patriarchy to recognize women not just for their financial successes but for the work itself. We need a different standard for success, to show people we can succeed on our terms. I’m a folk singer, not an entrepreneur.

Leviton: Maybe from the point of view of Ms., part of feminism is getting a fair share of the capitalist pie.

DiFranco: Well, from the time I was a kid, I knew that I had to have money to be free. In that sense, I guess I am an entrepreneur. But that’s all the money I need: enough to be free. When I was nine years old, I started taking my guitar to the Broadway Market in Buffalo and playing Beatles songs for tips. I made pressed-flower cards and sold them at my school. I did whatever I had to do to make my own money, so I could make my own choices. As long as you are beholden to somebody else for money, you’re in debt. But that’s the extent of my entrepreneurial spirit. It still strikes me as unfortunate that I was hailed as some kind of brilliant businesswoman. It feels denigrating to me.

Leviton: Comedians Richard Pryor and Lenny Bruce were big influences on you.

DiFranco: Yes, I got turned on to Lenny Bruce when I was young. I was using cuss words onstage, and I learned that he had paved the way for performers to say the unsayable, to speak freely. The cops would sometimes come and arrest him for indecency.

When I was a little kid in the late seventies, my father took my brother and me to see the movie Richard Pryor: Live in Concert. We were there for about ten minutes before he took us home. I later watched the whole movie, and it just blew my mind. I can understand why my father thought it was too explicit for us, but he respected Pryor enough to want to take us. My father recognized Pryor as an agent of social change.

I have used humor onstage from the beginning to put people at ease. I think anytime you can make people open their mouth — whether to laugh or gasp or cry — you can slip the pill in there. Once people are laughing, you can say things to them you can’t say in any other context.

I took a lot of cues from comedians. I’m a total goof. For years I was kind of a smile with legs. That big grin — that was my trademark. I was painfully self-effacing starting out. This job has definitely emboldened me. I used to be that shaking girl who was afraid to approach people. When people began approaching me, I thought, Wait, now I’m in the position of power? Once young women were idolizing me, it began to affect my perception of myself.

When I am off the road for a while, I start to fade back into my older, more passive personality. I let my husband set the rules in our house even when they feel wrong to me. I avoid contradicting people. I become the conflict-avoidance queen! Then I get back on the road, and I’m applauded and asked my opinion about everything, and my spirit reawakens. It’s amazing how different I feel after a few months on the road as opposed to a few months at home doing dishes. It really shows that even something as supposedly inherent as our personality is really a dance between many forces.

Leviton: How do you decide which political causes to support?

DiFranco: The way I see it, my feminism comes through my songs. I’m purposefully trying to uplift women with my music. So I have tended to focus my activism on other areas: antiwar efforts, criminal justice, race issues, anti-death-penalty work. I feel like you have to start by helping the people on the bottom. I think it’s great that young middle-class girls are going to “rock camp” to learn music these days, but if I’m going to play a benefit concert, I’d rather do it for the Southern Center for Human Rights.

Leviton: Do you want Hillary Clinton to become our first female president?

DiFranco: I love Bernie Sanders and would be excited to vote for him, but if Clinton is the nominee, I will be excited for different reasons. Sanders is a true public servant who’s been sticking up for people since the beginning, but Clinton, despite her political centrism, is, quite simply, female, so her election would be thrilling, because it would unlock that invisible door. Once that door is unlocked, I believe much goodness will walk through it. I know that the picture of Barack Obama’s face as president has done more, on one level, to liberate the future America than anything he could ever do as a politician. Little children do not know what is being said, but they know that man is the president. The idea that the first two presidents my eight-year-old daughter might know could be a person of color and a woman makes me want to cry with joy.

Leviton: What issues are most important to you?

DiFranco: Certainly racial injustice. Who knew that cellphone cameras would become weapons of civil rights? More than any statistic about arrests or police brutality, cellphone videos are waking up white America to how the system is biased. No amount of words can affect people as viscerally as a thirty-second clip of somebody being choked to death.

Leviton: What else do you care strongly about?

DiFranco: The reproductive rights of women are an important prerequisite to continuing the work of feminism. If you don’t have control over when to become a mother, you’re not free.

I’ve had people say to me, “Do you think feminism is still an important issue right now? We are in a state of perpetual war; there’s chaos in the Middle East.” I reply, “Absolutely.” We need to deal with the fundamental imbalance of power that is the cause of our social diseases.

Leviton: Feminists right now are fighting among themselves about transgender rights.

DiFranco: Sad but true. For instance, the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival, where I have performed, was attacked in recent years by the transgender community for its policy of admitting only “womyn born womyn” — no transgendered people who were born male. Over the years the policy has been loosely enforced. They have found ways for transgender people to come without compromising the principles of creating a safe space for women. Nevertheless, some acts have refused to play the festival because of its stance, and last summer, when the conflict still wasn’t peacefully resolved, the organizers decided to cancel further festivals.

We have an opportunity, now that we have a fractured Right, to become a galvanized Left. We need to unify, and continuing to engage with people who disagree with us is crucial. It’s not a simple thing: political activism is an art form that you have to study and practice.

Leviton: Historians identify feminism as having at least three “waves.” The first was the women’s-suffrage movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The second was the push for women’s rights in the sixties and seventies. Your career began around the start of the third wave, in the early nineties. What does being a “third-wave” feminist mean to you?

DiFranco: Truth is, I’m not even really sure what it means: second wave, third wave. The third wave is supposed to have brought about the racial diversification of feminism, but that seems like bullshit to me. Feminism’s second wave was highly diversified. In fact, I would say that African American women really drove the second wave and provided much of its inspiration. It was Audre Lorde’s “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” and Alice Walker’s In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens that changed my life. Gloria Steinem may have been the spokesperson of the second wave, but she often had a woman of color standing next to her — and not in a pandering way but out of genuine respect. So much ground that was gained in the seventies was then lost in the eighties with the election of Ronald Reagan and the country’s turn to the right. That same ground must now be regained in a climate that is ever more polarized and divisive.

Leviton: You don’t write topical protest songs in the manner of Phil Ochs or Tom Paxton, who calls such tunes “short-shelf-life songs.”

DiFranco: I’m always searching for the universal in the specific. I do respond to current events, though. I was on tour with Peter Mulvey this past June when the massacre happened at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. People quickly began to push for the removal of the Confederate flag from the state’s capitol, and Peter rose to the occasion and wrote “Take Down Your Flag.” He wanted to get the song out there and make it not just his but everybody’s. So he put out an open invitation for other artists to write their own verses. And he wanted to do this quickly, so he went through the Internet and social media. The experience was hard for him, because through those same channels came the backlash and the racist responses. I prefer the old-school way: you develop a song over time; you play it onstage for a while; then it’s released, and the reaction slowly comes back to you. It’s difficult to engage in a creative process when you get that immediate response because the song is on YouTube that night. The Internet might be a valuable tool for positive activism, but it casts as big a shadow. It’s as awful as it is good.

But I wanted to be a part of Peter’s effort, because I felt strongly that we needed to honor and remember the victims and the community that had been hit. The example that many of the victims’ family members set in the aftermath was transcendent. They showed remarkable compassion and forgiveness, humanizing the shooter in a way that I don’t think I could have if it were my son who’d been shot. To me that’s the message of Jesus and Martin Luther King Jr. That’s it. And if that goes unnoticed when people show it, how are we going to evolve? So I recorded Peter’s song, releasing my version last July, with all the money going to the Mother Emanuel Hope Fund.

Leviton: Your albums seem to be snapshots of what’s going on in your life at the moment. What are your current concerns?

DiFranco: The recent attacks on Planned Parenthood and the endless fight for reproductive freedom have angered me. I have a new song called “Play God,” with the chorus “You don’t get to play God, man / I do.” Choosing which eggs get to develop is playing God. I’ve had two abortions and given birth to two children, and I suspect I had a miscarriage once. And of course I have had more periods than I can count. What I can tell you is that nature is bloody and brutal, and creation goes hand in hand with death. Saying goodbye to a fertilized egg can be a heart-wrenching experience — but so can saying goodbye to an unfertilized egg sometimes. The ovum is by far the largest human cell, and I believe that some of them have such a powerful longing to become alive that their “death” can be devastating. What we call PMS feels to me like a grief that sets in when an unfertilized egg gives up its quest for life. It’s as if a part of you has just died, and you feel anger and sadness, and you see darkness everywhere. There’s a lot of death involved in living, and I think women experience that intuitively in a way men don’t. An abortion is a death, yes, but so is a period. Because women are forces of nature, and subject to all the dark forces, they also represent choice, playing God every time they give birth or don’t. Damn it, you have to trust your individual choices.

Leviton: It’s not just right-wingers who want to treat abortion as a big mistake. There are feminists who advocate holding healing ceremonies for miscarriages, stillbirths, and abortions.

DiFranco: This could easily turn into shaming. We need to see losing a fetus or choosing to end a pregnancy as a part of a larger process that keeps us all alive.

We really exist only in relationship to the whole. Our idea of ourselves as individuals is kind of a fallacy. Of course we have incredible individual powers, but if you see only that, the picture gets distorted. We should be aware we are each just a fraction of a whole, and that our time here is temporary. I believe consciousness — or “God,” if that’s your word for it — does not see us as individuals any more than we see each of the cells in our body as individuals. We learn in physics class that matter and energy cannot be created or destroyed. It seems obvious to me that if consciousness does not manifest itself in a particular fetus, it will simply coalesce in another. A woman who terminates a pregnancy is merely closing her door and asking to be passed over in favor of her neighbor whose door is open.

Leviton: Do you consider yourself a spiritual person?

DiFranco: Oh, yes. I regard most organized religions as nothing more than codified patriarchy, but they seem to have their roots in a human need to belong to something bigger than ourselves. I’ve found spiritual meaning in the struggle for peace and justice. Lifting other people up is as much a spiritual practice as being a priest or monk. It’s the people who write me letters or stop me on the street to tell me I improved their lives who give my life a sense of purpose and meaning.

My parents instilled in me the idea of the collective. When my mom went door-to-door canvassing for local women in politics, she took me along. I licked stamps for mailings when she was starting a food co-op in our neighborhood. She taught me to be kind to people. She set an example for me of right and wrong, and responsibility.

I never knew any of my grandparents, because my parents were older than most: my mother was forty when I was born, and my father, fifty. He was the son of Italian immigrants and had always loved American art: Martha Graham, Aaron Copland, Woody Guthrie. He had such respect for artists, and he wanted to exercise all the political rights our society gives us. When my father was dying in 2004, I was happy to hear my mother’s last words to him: “You gave me these two kids; you gave me art; you gave me politics; you gave me culture.” Growing up, I’d always thought of my mom as the engaged one, but when I heard her say that to him, I appreciated how they’d both instilled in me the desire to be a part of something. That might sound political, but to me it’s spiritual.

Leviton: Now that you have kids of your own, do you see your mother differently?

DiFranco: Well, becoming a mother has certainly made me appreciate all the sacrifices a parent makes. I’ve also been unlearning a lot of bad behaviors. When my daughter was born, I quickly became aware that it doesn’t matter what I say; it’s how I act that my children pay attention to. As I tried to teach them the best way to behave, it became obvious to me that I didn’t always behave that way, and I wanted to. How many of us really do what we ask our children to do?

Leviton: In 2013 a controversy erupted when you scheduled an event called “Righteous Retreat” at the Nottoway Plantation and Resort in White Castle, Louisiana. It’s a luxury hotel and convention center on land that, like much of the rural land in the South, used to be a slave plantation. First of all, what was the event supposed to be about?

DiFranco: The idea was to have seminars and classes over four days and maybe inspire other artists and musicians in their own work. To make myself available to 150 people for that long was a daunting proposition, but it was a part of my effort to reduce the amount of time I had to be on the road, away from my kids. With a four-day intensive workshop I could earn the same money I did in a month on the road.

A promoter who’d done a similar event at Nottoway the previous year had planned it all out, and I’d agreed without knowing the exact location, only that it was near New Orleans. My son was six months old, and I was not giving a lot of thought to my career just then. For my co-faculty I picked Toshi Reagon, Buddy Wakefield, and Ed Hamell — three very political, poetic, kindred spirits.

When I found out that the name of the hotel was Nottoway Plantation, I was shocked, but I didn’t automatically think it was incorrect for my crew and me to inhabit that space. Toshi is black and had played at a former plantation before.

The woman who spearheaded the criticism of the event had done her research, which I certainly hadn’t, and she’d discovered a promotional pamphlet describing the slave owner of this plantation as on the benevolent side, someone who’d tried to “maintain a willing workforce.” Willing is a pretty offensive word to apply to slavery.

I regard most organized religions as nothing more than codified patriarchy, but they seem to have their roots in a human need to belong to something bigger than ourselves. I’ve found spiritual meaning in the struggle for peace and justice. Lifting other people up is as much a spiritual practice as being a priest or monk.

Leviton: A petition was circulated asking you to cancel the event, and you eventually did pull out and wrote an apology.

DiFranco: First the controversy built on social media for two or three weeks, and Scot chose not to tell me. He took the position of “It’s not Ani’s job to get involved in every dispute about her work.” In retrospect that was a grave mistake.

When I eventually became aware of the controversy, I thought I had to respond that day. I was emotional and made a misstep: I tried to explain my side, how I perceived it. I pointed out, for example, that any older building in the South had been constructed, directly or indirectly, by slave labor, and that to avoid using such buildings, I would have to move far away from New Orleans. You can stand on any street corner in New Orleans and see these skinny buildings with oddly shaped roofs that everyone knows were once slave quarters. I also asked whether I should investigate the history and ownership of all the venues where I played: the performing-arts centers, the theaters, the nightclubs.

This only provoked more fierce reactions. I see now that I should have just said, “I’m sorry,” and affirmed people’s pain. “Sorry” would have shown that I was listening. And a few days later I released another statement saying just that. My white privilege had snuck up on me. The attacks had made me reexamine myself. Places like Nottoway need the most awareness and the most healing. When you have a wound, you can’t turn away. You have to address it, or it gets worse and worse.

I’m still feeling the effects. It’s devastating to be kicked out of the tribe, you know? And this was my first experience of following my instincts and having them lead me wrong. It was very instructive for me: I learned what it feels like to be afraid to be yourself and to speak your mind. It made me want to give up. Certainly I wanted to shut down any outreach, have no online presence at all. I even wanted to shut down Righteous Babe Records and figure out something else to do. But Scot brought me back from the edge.

The fires of racial injustice are perpetually burning in this country, and if you pour a little gasoline on them, watch out. In the aftermath a lot of poison was thrown back and forth online between fans of my music. I stayed out of it. It would have been impossible for me to try to police that. There’s a reason I’m not on the Internet.

The only lie I told, in retrospect, was in my second statement, when I said I was sorry I’d been unavailable to my fans online. I never intend to be available to anyone on social media that way. I need quiet around my creativity and my heart. Social media is like the Roman Colosseum: a place where people do battle for spectacle. I can’t even go there.

The culture is changing, but I’m not. In the early days everyone in the audience was really paying attention. Now people have their cellphones out filming or calling their best friend when I play a certain song. Sure, maybe you need to call the baby sitter, but I’m looking out into the darkness and finding one face over here lit by the blue light of a phone screen and another blue face over there. Those are the people I see — the ones who have checked out and gone into their devices. We have an invocation at the start of each show in which we dare people to turn their cellphones off and spend ninety minutes together in person. Without cellphones, it’s like we get into a boat together and sail off.

I use my cellphone very little, and when I do, my two-year-old lets me know that it’s a violation of being present. He teaches me to put the phone down. He reminds me that even pulling it out to take a picture of him when he’s doing something cute ends the moment. It’s an alienating part of our culture that we don’t even notice. We become ever more alienated even as we become ever more connected.

Leviton: Before we finish up, I want to talk about your poem “Self Evident,” which you wrote after the 9/11 attacks of 2001 and recorded with musical backing the following year. You were angry about many of the things I was angry about then, but it seemed to me that, in your haste to make political points about President George W. Bush and his administration, you showed insufficient sympathy for the loss of life. I thought you’d crossed a line.

DiFranco: I was in Manhattan auditioning horn players on 9/11. It was surreal. A few people did show up. There was a huge parrot in the rehearsal studio that screamed all day long. The bird felt the atmosphere.

I had a tour scheduled, and many musicians were canceling appearances, but I felt it wasn’t the time to go inside and be alone; we had to face this together. I needed to interact with audiences. So I went out on the road. I started writing “Self Evident” and performing different versions of the poem every night. After many months I felt it was done.

The poem says, “You can keep the Pentagon / Keep the propaganda / Keep each and every TV / That’s been trying to convince me / To participate in some prep-school punk’s plan to perpetuate retribution / Perpetuate retribution / Even as the blue toxic smoke of our lesson in retribution / Is still hanging in the air.”

I performed “Self Evident” in Carnegie Hall in April 2002, before a full house. When I walked out on stage, I was thinking about the people in that room and who they might have lost on 9/11. While I was performing that poem, I heard sobbing, and I thought, What am I doing? I didn’t think this through. But I kept going. I’ll never know what happened that night, whether it was hurtful or cathartic for that audience.

I’m not a perfect person. I can’t know the effect of everything I do. It’s important to push society, but it’s also important to take care. In retrospect, I wouldn’t change the poem. I was trying to place the blame where I thought it belonged: on the people who were supposed to be taking care of us and instead had put us in jeopardy.

I was recently talking to a friend who once gave a dance/theater performance that dealt with rape. She got lots of reactions, not all of them positive. People said, “Somebody could show up to this performance who’s been raped, and what is that going to feel like to them?” But should we not put challenging works of art out there because of those risks, because of the pain that’s involved? How much right does an artist have to cause pain while trying to heal? Who can answer these questions? Each of us finds a balance. I’ve always leaned toward just saying what’s true for me. If it’s real, and it happened, and you felt it, you have every right to tell it. But I certainly regret certain things I’ve said onstage. I’m still evolving.