THE BEAR TAKES seven steps, her claws clicking on concrete. She dips her head, turns, and walks toward the front of the cage. Another dip, another turn, another three steps. When she gets back to where she started, she begins all over. This is what’s left of her life.

Outside the cage, people pass by on a sidewalk. Parents stop strollers until they realize there’s nothing here to see. A pair of teenagers approach, wearing Walkmans and holding hands; one glance inside is enough, and they’re off to the next cage. Still the bear paces; three steps, head dip, turn.

My fingers are wrapped tightly around the metal railing outside the enclosure. I notice they’re sore. I look at the silver on the bear’s back, the concave bridge of her nose. I wonder how long she’s been here. I release the rail, and as I walk away, the rhythmic clicking of claws on concrete slowly fades.

Unfortunately most of us by now have been to enough zoos to be familiar with the archetype of the creature who has been driven insane by confinement: the bear pacing a precise rectangle; the ostrich incessantly clapping his bill; the elephants rhythmically swaying. But the bear I describe is no archetype. She is a bear. She is a bear who, like all other bears, at one time had desires and preferences all her own, and who may still, beneath the madness.

Or at this point she may not.

ZOO DIRECTOR David Hancocks writes: “Zoos have evolved independently in all cultures around the globe.”

Many echo this statement, but it isn’t quite true. It is the equivalent of saying that the divine right of kings, Cartesian science, pornography, writing, gunpowder, chain saws, backhoes, pavement, and nuclear bombs have evolved independently in all cultures around the globe. Some cultures have developed zoos, and some have not. Human cultures existed for scores of thousands of years prior to the first zoo’s appearance about 4,300 years ago in the Sumerian city of Ur. And in the time since the first zoo, thousands of cultures have existed with no zoos or their equivalents to be found.

Zoos have, however, evolved in many cultures, from ancient Sumer to Egypt to China to the Mongol Empire to Greece and Rome, on up the lineage of Western civilization to the present. But these cultures share something not shared by indigenous cultures such as the San, Tolowa, Shawnee, Aborigine, Karen, and others who did not or do not maintain zoos: they’re all “civilized.”

The change of just one word makes Hancocks’s sentence true: “Zoos have evolved independently in all civilizations around the globe.”

Civilizations are characterized by cities, which destroy natural habitats and create environments inimical to the survival of many wild creatures. By definition, cities separate their human inhabitants from nonhumans, making it a challenge for urban residents to establish daily, neighborly contact with wild animals. Until the onset of civilizations — for 95 percent of our existence — this contact was central to the lives of all humans, and to this day it remains integral to the lives of the “uncivilized.”

If it can be said that relationships form us, or at the very least influence who we are, then the absence of this fundamental daily bond with wild, nonhuman others will change our sense of self, how we perceive our role in the world, and how we treat ourselves, other humans, and those who are still wild.

IF YOU SEE an animal in a zoo, you are in control. You can come, and you can go. The animal cannot. She is at your mercy; the animal is on display for you.

In the wild, the creature is there for her own purposes. She can come, and she can go. So can you. Both of you can display as much of yourselves to the other as you wish. It is a meeting of equals.

And that makes all the difference in the world.

One of the great delights of living far from the city is getting to know my nonhuman neighbors — the plants, animals, and others who live here. Although we’ve occasionally met by chance, I’ve found that it is usually the animals who determine how and when they reveal themselves to me. The bears, for example, weren’t shy, showing me their scat immediately and their bodies soon after, standing on hind legs to put muddy paws on windows and look inside; or offering glimpses of furry rumps that disappeared quickly whenever I approached on a path through the forest; or walking slowly like black ghosts in the deep gray of predawn. Though I am used to their being so forward, it is always a gift when they reveal themselves, as one did recently when he took a swim in the pond in front of me.

Robins, flickers, hummingbirds, and phoebes all present themselves, too. Or rather, like the bear, they present the parts of themselves they want seen. I see robins often, and a couple of times I’ve seen fragments of blue eggshells long after the babies have left, but I’ve never seen their nests.

These encounters — these introductions — are on terms chosen by those who were on this land long before I was: they choose the time, place, and duration of our meetings. Like my human neighbors and friends, they show me what they want of themselves, when they want to show it, how they want to show it, and for that I am glad. To demand they show me more — and this is as true for nonhumans as it is for humans — would be unconscionably rude. It would destroy any potential our relationship may once have had. It would be unneighborly.

I am fully aware that even a young bear can kill me. I am also fully aware that humans have coexisted with bears and other wild animals for tens of thousands of years. Nature is not scary. It is not a den of fright and horrors. For almost all of human existence, it has been home, and the wild animals have been our neighbors.

Right now, worldwide, more than 1 million people die each year in road accidents. In the United States alone, there are about forty-two thousand traffic fatalities a year. Yet I am not afraid of cars — though perhaps I should be. Around the world, nearly 2 million people per year are killed through direct violence by other people. Almost 5 million people die each year from smoking. And how many people do bears kill? About one every other year in all of North America.

We are afraid of the wrong things.

I’M AT A ZOO. Everywhere I see consoles atop small stands. Each console has a cartoonish design aimed at children, and each has a speaker with a button. When I push the button, I hear a voice begin the singsong: “All the animals in the zoo are eagerly awaiting you.” The song ends by reminding the children to be sure to “get in on the fun.”

I look at the concrete walls, the glassed-in spaces, the moats, the electrified fences. I see the expressions on the animals’ faces, so different from the expressions of the wild animals I’ve seen. The central conceit of the zoo, and in fact the central conceit of this whole culture, is that all of these “others” have been placed here for us, that they do not have any existence independent of us, that the fish in the oceans are waiting there for us to catch them, that the trees in the forests stand ready for us to cut them down, that the animals in the zoo are there for us to be entertained by them.

It may be flattering to believe that everything is here to serve you, but in the real world, where real creatures exist and real creatures suffer, it’s narcissistic and dangerous to pretend nobody matters but you.

SOMETIMES I fantasize about imprisoning zoo advocates and zookeepers to give them a taste of their own medicine. I would confine them for a month and then ask if they were still eager to make jokes about the pacing monkey they call “Jogging Man.” I would ask them if they felt grief, sorrow, resentment, and homesickness, and if they still believe that animals do not need freedom. I wouldn’t listen to their answers, though, because I would not care to hear about their experiences. In fact, I wouldn’t believe that these zookeeper animals — for humans are animals, too — could meaningfully experience the world, which means it would be a projection on my part to believe they had anything to tell me. Indeed, it would be a projection on my part to believe these animals might wish a certain condition to continue or change.

I would leave the human animals there, in their cages, and I would ask them these questions again in a year. During that time they would never be allowed to speak to another human, but they would be given cardboard boxes and paper bags to play with. I think that after twelve months of confinement they would tell me they agreed that animals need freedom. But I would not listen to them. I would not believe they could speak. I think that in time they would no longer tell me anything at all; they would silently walk around their cages — their “habitats” — taking seven steps forward, dipping their heads, turning to the left, and back again.

IT IS OFTEN SAID that one of the primary positive functions of zoos is education. The ending to the standard zoo book uses elevated language to state that because the earth has become a battlefield with the animals losing the war, zoos really are the last hope for beleaguered wildlife. Only through unleashing the full potential of zoos for education will people ever learn to care enough about wildlife not to destroy the planet. As author Vicki Croke puts it, the challenge for zoos is “to allow living, breathing animals to inspire wonder and awe of the natural world; to teach us that animal’s place in the cosmos and to illuminate the tangled and fragile web of life that sustains it; to open the door to conservation for the millions of people who want to help save this planet and the incredible creatures it contains.”

Have you watched people at zoos? I see no awe and wonder on their faces. Instead I hear children laughing at the animals — not the sweet sound of innocent laughter, but the derisive kind you hear in the schoolyard: the laughter at someone else’s misfortunes. I see parents and children giggling at the fat orangutan, making scary faces at the snake, ignoring the pacing bear. They shriek at the silly monkeys who pick their noses and stare straight through the glass at them. The children laugh and pound on the window.

Even if we accept at face value the claims for the educational potential of zoos, study after study has shown that zoos fail miserably at this task. A tally of observation periods at the London Zoo found that spectators stood in front of the monkey enclosure for an average of forty-six seconds. These forty-six seconds included time spent reading — or, rather, skimming — the information posted about the animals. Not surprisingly, studies show low retention rates: even while patrons are in the zoo, standing directly in front of the animals in question, they consistently fail even rudimentary nomenclature questions: they still call gibbons and orangutans “monkeys”; vultures “buzzards”; cassowaries “peacocks”; otters “beavers”; and so on.

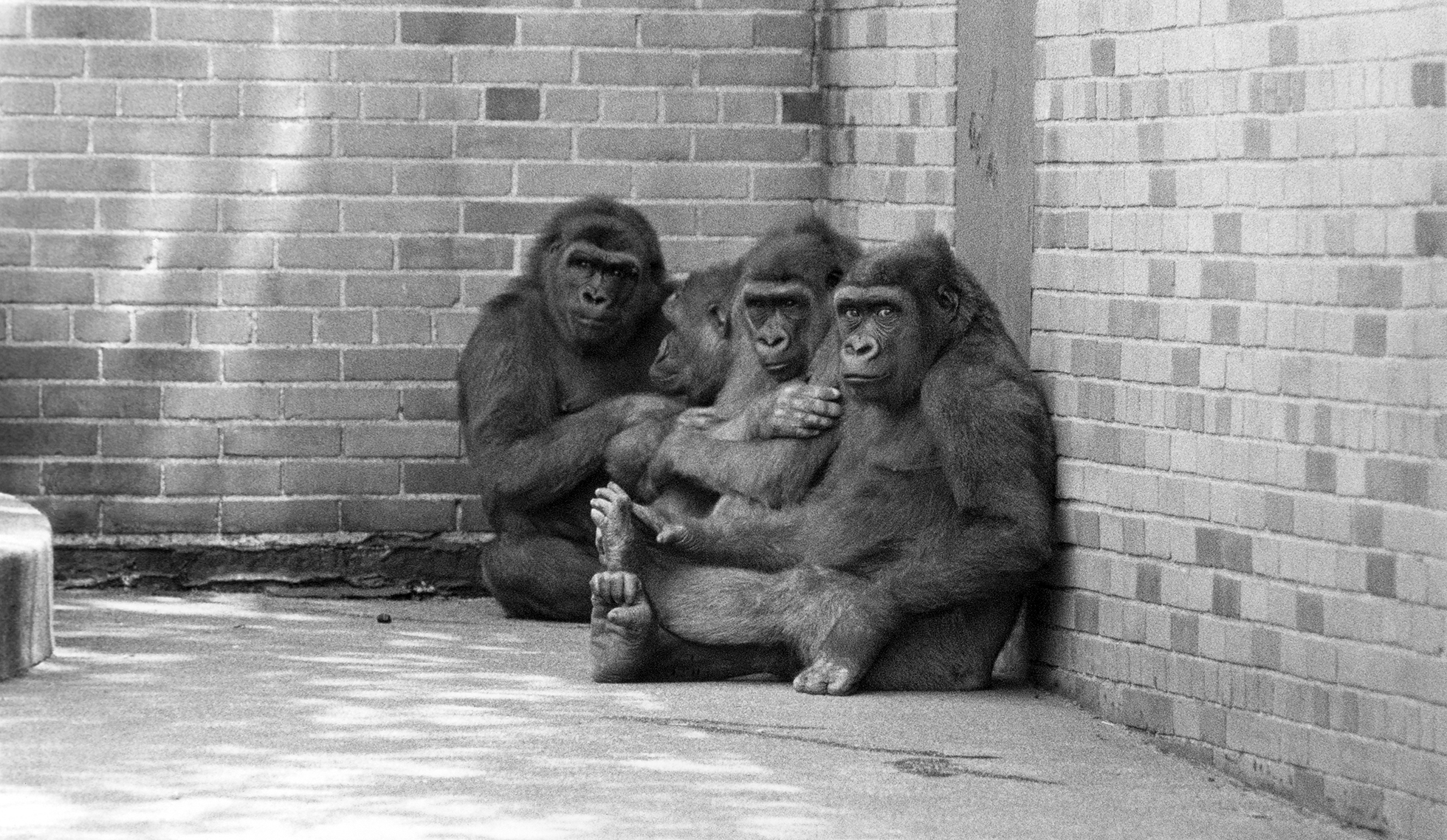

THE TRADITIONAL method for capturing many social creatures, including elephants, gorillas, and chimpanzees, was — and, in some cases, is — to kill the mothers. Most of us never hear about this; much better to believe that zoos rescue animals from the wild. To hear the truth about how animals are captured would impinge on the fantasy that the eager ocelots and elephants are “waiting” to meet us. Zookeepers know this. They have always known it. William Hornaday, director of the Bronx Zoo, wrote in 1902 to Carl Hagenbeck, considered by many to be the father of the modern zoological gardens and a trader in animals on an almost inconceivable scale: “I have been greatly interested in the fact that your letter gives me regarding the capture of the rhinoceroses; but we must keep very still about forty large Indian rhinoceroses being killed in capturing the four young ones. If that should get into the newspapers, either here or in London, there would be things published in condemnation of the whole business of capturing wild animals for exhibition.”

If you are a mother, what would you do if someone tried to take your child? When you were a child, how would you have felt if someone shot your mother so they could put you on display? What would you feel as you poked at her, hit her, wanted her to wake up so together you could make your escape, but she did not awaken? What would you feel if they put you in a cage?

These are not rhetorical questions. What would you do? What would you feel?

ONE OF THE THINGS I dislike most about Western culture is the unexamined belief that humans are superior to and fundamentally separate from “the animals”; that animals are animals, and that humans are not animals; that an impermeable wall stands between.

In this construct, humans are intelligent. Animals — by which is meant all animals except humans — are not, or if they do have any sort of intelligence, it is dim, rudimentary, just sufficient to allow them to meaninglessly navigate their meaningless physical surroundings.

Whereas human behavior is based on conscious, rational choices, our culture suggests animal behavior is fully driven by instinct. Animals do not plan, do not think. They are essentially machines made of DNA, guts, and fur, feathers, or scales.

Humans feel a wide range of emotions. Animals reportedly do not. They do not grieve the loss of a mother, of freedom, of a world. They do not feel sorrow. They do not feel joy. They do not feel homesickness. They do not feel humiliated.

This culture thinks that human life is sacred (at least, some human life is sacred, but the lives of the poor, the nonwhite, the indigenous, as well as the lives of any who oppose the wishes of those in power, are only a little sacred, or sometimes not sacred at all), but animal life is not sacred. In fact, the entire animate world is not sacred.

Humans are supposedly the sole bearers of meaning, the sole definers of value, the only creatures capable of moral behavior. Animals’ lives have no inherent value — indeed, no value at all, except insofar as value is assigned to them by humans. This value is almost always strictly utilitarian. Most often it is monetary, and usually it is based not on their lives but on the price of their carcasses. And, of course, animals are incapable of moral behavior.

Finally, this culture constantly stresses that all that is human is good: humans have humanity and are humane; the civilized are civil. Human traits are to be loved. Animal traits are to be hated — or, rather, hated traits are projected onto animals. Bad humans are “animals,” “brutes,” and “beasts.” My thesaurus lists as synonyms for animal: inferior, mindless, unthinking, intemperate, sensualist.

We are discouraged from anthropomorphizing animals — that is, we shouldn’t attribute human characteristics to them. This means that we must do everything within our power to blind ourselves to animals’ intelligence, their awareness, their feelings, their joys, their suffering, their desires. It means we must ignore their selfhood, their individuality, and their value entirely independent of our own uses for them.

WHAT DO WE really learn from zoos? We learn that we are here, and animals are there. We learn that they have no existence independent of us. We learn that our world is limitless, and their worlds are limited, constrained. We learn that we are cleverer than they are, or they would outwit us and escape — or maybe that they do not want to escape, that the provision of bad food and concrete shelter within a cage is more important to them than freedom. We learn that we are more powerful than they are, or we could not confine them. We learn that it is acceptable for the technologically powerful to confine the less technologically powerful. We learn that every one of us, no matter how powerless we may feel in our own lives, is more powerful than the most mighty elephant or polar bear.

We learn that “habitat” is not unspoiled forests and plains and deserts and rivers and mountains and seas, but concrete cages with concrete rocks and the trunks of dead trees. We learn that “habitat” has sharp, immutable edges: everything inside the electrified fence is “bear habitat,” and everything outside the fence is not. We learn that habitats do not meld and mix and flow back and forth over time.

We learn that you can remove a creature from her habitat and still have a creature. We see a sea lion in a concrete pool and believe that we’re still seeing a sea lion. But we are not. We should never let zookeepers define for us what or who an animal is. A sea lion is her habitat. She is the school of fish she chases. She is the water. She is the cold wind blowing over the ocean. She is the waves that strike the rocks on which she sleeps, and she is the rocks. She is the constant calling back and forth between members of her family, this talking to each other that never seems to stop. She is the shark who eventually ends her life. She is all of these things. She is that web. She is her desires, which we can learn only by letting her show us, if she wants; not by caging her.

We could and should say the same for every other creature, whether wolverine, gibbon, macaw, or elephant. I have a friend who has spent his life in the wild and ecstatically reported to me one time that he’d seen a wolverine. I could have responded, “Big deal. I’ve seen plenty in zoos. They look like big weasels.” But I have never seen a wolverine in the wild, which means I have never seen a wolverine.

Zoos teach us that animals are meat and bones in sacks of skin. You could put a wolverine into tinier and tinier cages, until you had a cage precisely the size of the wolverine, and you would still, according to what zoos implicitly teach, have a wolverine.

Zoos teach us that animals are like machine parts: separable, replaceable, interchangeable. They teach us that there is no web of life, that you can remove one part and put it into a box and still have that part. But that is all wrong. What is this wolverine? Who is this wolverine? What is her life really like?

Zoos teach us implicitly that animals need to be managed, that they can’t survive without us. They are our dependents; not our teachers, our neighbors, our betters, our equals, our friends, our gods. They are ours. We must assume the interspecies version of the white man’s burden and, out of the goodness of our hearts, benevolently control their lives. We must “rescue them from the wild.”

Here is the real lesson taught by zoos, the ubiquitous lesson, the inescapable lesson, the overarching lesson, and really the only lesson that matters: that a vast gulf separates humans and all other animals. It is wider than the widest moat, stronger than the strongest bars, more certain than the most lethal electric fence. We are here. They are there. We are special. We are separate.

THE PRETENSE that humans are superior to nonhumans is entirely unsupportable. I have seen no compelling evidence that humans are particularly more “intelligent” than any other creature. I have had long and fruitful relationships with many nonhuman animals, both domesticated and wild, and have reveled in the bouquet of radically different intelligences — different forms, not different “quantities” — that they have introduced to me, each in his or her own time, in his or her own way.

Similarly, I have seen no evidence that animals do not plan, do not remember, do not hold grudges, do not squabble, do not have communities, do not grieve, do not feel joy, do not play games, do not make jokes, do not enjoy challenges, do not have fun, do not have morals, do not feel or think so many of the things that are so arrogantly deemed to be human traits. Indeed, I have seen all of these “human” traits in nonhuman animals.

An example: Late the other night one of my dogs woke me with his barking. I stood and looked outside. It was a beautiful full-moon night. I asked him to be quiet. He groaned and lay down. I went to bed. He started barking again. I got up again and asked him to be quiet. He groaned, walked in circles, and lay down. I went to bed. He started barking. I got up and yelled at him to shut up. He was quiet. The next morning he was gone. Later that day I walked to my mom’s house. He was there. He wouldn’t look at me. Normally he goes everywhere with me, but when we came home he demurred. It wasn’t until the day after that he would look at me, and even then it was only after several apologies and a bunch of dog treats. Slowly, he seemed to forgive me.

My refusal to stay up with my dog that night had no rationale; I had no appointment early the next morning, and it was a beautiful night. I don’t see how the fact that I can type on a computer keyboard makes me any smarter in this case than a dog who at least has the sense to play in the moonlight.

HUMANS VISIT ZOOS because we need contact with wild animals. We need the animals to remind us of the enormous complexity of life, to remind us that the world was not made just for us, to remind us that we are not the center of the universe. We need them to teach us how to live.

Children need this contact even more than adults. It is no coincidence that most zoo visits are instigated by children, nor that children are interested in animals’ anatomical features and names. Children want — need — to go to zoos because they understand in their bodies the developmental necessity of being in the presence of wild animals. They understand, but of course cannot articulate, that to fail to enter into these relationships with nonhuman others is to take a major and often irreversible step into the delusion-inducing echo chamber of human-centered thought. If, as ecologist Paul Shepard has said, “nature is the child’s tangible basis upon which symbolic meanings will be posited,” and if the child does not experience nature, then the child — and later the adult — will have a warped sense of meaning.

But a child who goes to a zoo is not encountering real animals. Like any other spectacle, like any other form of pornography, a zoo can never really satisfy, can never really deliver what it promises. Zoos, like pornography, offer superficial relationships based on hierarchy, dominance, and submission. They depend on a detached consumer willing to observe another who may or may not have given permission to be the object of this gaze.

Think of a pornographic picture. Even in cases where women are paid and willingly pose for pornography, they have not given me permission to see their bodies — or, rather, images of their bodies — right here, right now. If I have a photograph, I have it forever, even if subsequently the woman withdraws her permission. This is the opposite of relationship, where the woman can present herself to me now, and now, and now, always at both her and my and our discretion. What in a relationship is a moment-by-moment gift becomes in pornography my property, to do with as I choose.

And so it is with zoos. Zoos take a very real, necessary, creative, life-affirming, and — most of all — relational urge and turn it, pervert it. Pornography takes the creative relational need for sexual contact with a willing partner — and the intimacy this can imply — and simplifies it to the relationship of watcher and watched. Zoos take the creative need for participating in relationships with wild, nonhuman others and simplify it until our “nature experience” consists of spending a few moments looking at — or simply walking by — bears and chimpanzees in concrete cages.

Incarcerating animals in zoos is to entering into relationships with them in the wild as rape is to making love. The former in each case requires coercion; limits the freedom of the victim; and springs from, manifests, and reinforces the perpetrator’s self-perceived entitlement to full access to the victim. The former in each case damages the ability of both victim and perpetrator to enter into future intimate relationships. Based on the dyad of dominance and submission, it closes off any possibility for real and willing understanding of the other.

A real relationship is a dance among willing participants who give what they wish, as they wish, when they wish. It inspires present and future intimacy, present and future understanding of the other and the self. It nourishes those involved. It makes us more of who we are.

IN MY WRITING, I don’t often present tangible solutions to the problems we face. This is because, for the most part, these problems are symptoms of and endemic to deeper psychological and perceptual faults, which means “solving” a problem technically without addressing these underlying faults will simply cause the pathology to present itself in a different way.

That said, I think I see a straightforward solution to the problem of children needing encounters with wild animals and zoos providing only parodies of these encounters. The solution is to let your child explore nature. I’m not talking about getting in the car to hang out with all the other tourists at Yosemite, effectively exchanging your city-based traffic jam for a nature-based one. To drive through nature is not all that different from being surrounded on four sides by movie screens as the visuals of a road rush up to greet you. Throw in the rocking of the car and some pine-scented freshener into the air vents, and the simulation will be more or less complete: you might even think you’re there.

Hiking is not all that much better. You’re still a tourist. No matter how spectacular Yosemite and Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon are, they’re still spectacles unless you live there. Unless you call it your home. Unless it says it’s your home.

I’m talking about staying home.

Although I traveled extensively as a child, I gained my love of nature; learned how to think, name, and categorize; and, for that matter, discovered who I was mainly in the window wells and backyard of my home, and beyond that in a pasture, and beyond that in an irrigation ditch. I learned far more from toads and salamanders at home than I did from all the vacations, all the hikes, all the backpacking, all the four-wheeling — and, yes, all the visits to natural-history museums and zoos. My teachers were the grasses, ants, and grasshoppers in the pasture; the snakes and crawdads in the irrigation ditch. The lessons and encounters weren’t all that extraordinary. And that is precisely the point: we were just neighbors.

I can hear your voice, somewhat incredulous, asking, “Just go outside? That’s boring.”

Good, I respond. Boredom can be a good state; it simply means you’ve not yet found what you want to do. As such, boredom can be an important preparatory step toward new understanding or action, as long as you have the courage and patience not to bail out too early. If you’re bored and you don’t like the feeling, you’ll soon enough find something to do. Or maybe something, or someone, will find you. In fact, I don’t think it’s too much to say that boredom plus freedom often equals creativity.

Boredom can also help us slow down. We are so accustomed — from zoos, from nature programs, from television, and even more generally from the speed of this culture — to events occurring on command. I send an e-mail and expect it to arrive in Bangkok seconds later. I turn on the television and can be watching a movie in an instant. But snakes and spiders run on their own time, a slower time. If you see a spider on a nature program, she will most likely kill something — or, rather, someone — during her few moments of screen time. But right now I’m looking at spiders on my wall, and they sit for hours, sometimes days. I often wonder what they’re experiencing. I’ll probably never know. I certainly won’t know unless they communicate with me. And even if they do that, I won’t perceive it unless I’m paying attention, and unless I’ve learned at least a little of their language. And that, once again, is precisely the point.

Hummingbirds and whirligig beetles run on different time, too; they’re always moving, spinning, doing something. They always seem breathless, or maybe it’s just that watching them makes me lose my breath. And what are the hummingbirds conceiving of as they swoop above my head, chirping? What are the whirligig beetles conjuring as they dance? It’s the same answer as with the spiders, and the same crucial point.

As children know, boredom is a nonissue anyway. The one time as a child I came in from the pasture to complain to my mom that I was bored, she said, “Good. Why don’t you clean the dirty dishes in the sink? After that, the garden needs weeding, and after that . . .” It worked. I never again complained of boredom.

Now I can hear your voice again. This time you say, “That’s all very good for you, Mr. Hayseed Country Boy, but what about those of us who live in cities?”

I pondered this question while sitting on the grass between Highway 101 and the McDonald’s parking lot. The only interesting thing I saw at first was an encircled A (for anarchy) on a concrete wall. But soon I noticed the tiniest red flower on a short and slender green stalk, and the shoots of other plants preparing for next spring. No animals, though. Then suddenly a bumblebee crawled from beneath the weeds, made her way under and over twigs to the edge of the grass, began flying, circled the weeds two or three times, and took off above the McDonald’s. Something clicked inside, and I was then able to see and hear the animals all around: spiders hunkered in the grass; ravens squawked over the sounds of trucks on the highway; sparrows hopped beneath cars.

Life is everywhere. Even in cities we can see creatures who are still wild and free, who can remind us that not all creatures are slaves. There are parks; there are alleyways; there are vacant lots; there are streams, rivers, and ponds; there are birds; there are insects. This culture has polluted and harmed so much land that it’s easy to think of unspoiled places as sacred and polluted places as sacrifice zones. But the truth is that all places are sacred. Beneath the pavement life is still there, waiting for us to remember; or if we fail to remember, waiting for us to die off. In either case, life persists, even in seemingly barren places.

“But,” I hear you again, “bumblebees and sparrows are boring. My child wants exciting animals.”

I’m not sure how watching a bear pace on concrete is more exciting than seeing wild creatures flying, hopping, crawling, doing what wild creatures do. Why are the animals at home less worthy? Is it because these others are from far away? Is it because the local animals are not in cages, and therefore not under our control?

It seems pretty clear to me that if you want your children to see larger animals, then you need to live in such a way that those larger animals want to live near you. You have to work to give them habitat. You need to make yourself worthy of their presence.

But even if you and your child restore habitat to welcome the animals home, you may not always see them when you want. As a child I sat beside many holes, willing snakes to come out so I could get a quick glance, but they rarely accommodated me. I’d see them only later, when walking or reading or watching someone else. I finally learned it’s not nice to look at someone who does not want to be looked at.

And who could blame the animals for hiding? Most of the apes with clothes are at this point treating those who are not Homo supremus maximus pretty poorly. If I were not an ape with clothes, I would hide too. But I can guarantee from my own experience that if you sit long enough and ask nicely enough and work hard enough to do what is in these others’ best interest, you will see marks of their existence. It might be subtle, like alder saplings deep in the forest chewed at forty-five degrees by mountain beaver; or it might be overt, like fox scat wrapped in leaves, or the feathers and beak of a robin left behind by a hawk; or it might be unmistakable, like a big, furry bear butt pressed up against your sliding glass door.

But it will be there.

The important thing is to look where you live. No, it’s to live where you live. It’s to stop searching the world over — including the “world in a box” approach of a zoo — for some great new exotic animal experience that will somehow change your life forever, or maybe just be a spectacle novel enough to stave off the tedium for a little while. The important thing is to stop disrespecting the creatures with whom you already share a home, stop ignoring them, stop considering them uninteresting simply because they are not exotic.

YEARS AGO I HEARD a story of a Native American spiritual leader who was in a circle with several environmentalists who were drumming and singing. One of the environmentalists prayed, “Please save the spotted owl, the river otter, the peregrine falcon.” The Native American got up and whispered, “What are you doing, friend?”

“I’m praying for the animals,” the environmentalist replied.

“Don’t pray for the animals. Pray to the animals.” The Native American paused, then continued, “You’re so arrogant. You think you’re bigger than they are, right? Don’t pray for the redwood. Pray that you can become as courageous as a redwood. Ask the redwood what it wants.”

As it says in the Bible, “Ask, and ye shall receive.”

Ask the pandas what they want. They will tell you. The question is: Are you willing to do it?

TO TAKE A BREAK from writing, I walk to the pond and notice that something is different. I freeze, scan. Then I see her, a great blue heron standing on a small rise above the far side. Her head is up, and her chest is out, aimed toward the sun. Her wings are half extended, and she stands, warming herself. I look at her a moment, then back away slowly, not wanting to startle her.

I smile and ask, softly, “Who are you? What do you want?”

For now, a grizzly bear still paces rectangles in a cage in a zoo. An elephant still sways hour after endless hour, chained to a concrete floor. A wolf still strides inside an electrified fence. A giraffe still stands in a cell too small for her to break into a run.

Perhaps some of these animals still remember what it was like not to be a prisoner. Perhaps some were born in zoos and have no firsthand knowledge of what it was like to live free, to run, to live in a family, a community, a land base. Perhaps they know it only from what their parents told them, who knew it only from what their parents had told them, who knew it only from vague memories before their own parents had been killed. Or perhaps they — like so many of us — have forgotten. Perhaps for them, as for many of us, this nightmare has become the only reality they know.

They have the excuse of being literally confined. We do not. We can walk away from our own zoo, our own myth of self-perceived separation from and superiority to other animals, this nightmare into which we have pulled all of these others. If this horrific dream is going to have any end but death — for its individual victims, and for the planet — it is up to us to awaken.

I type those words and then look away from the computer screen, out the window and into the sunlight. There is no wind. Even the bright green tips of the redwood branches are still. It’s beautiful. And then I see it: a shadow the shape of a heron moving dark over the bright green. The shadow is there for only a moment, and then it’s gone.

Writer Derrick Jensen and photographer Karen Tweedy-Holmes are both longtime contributors to The Sun. After they met through the magazine, the two discovered a shared interest in animals and ended up collaborating on the book Thought to Exist in the Wild: Awakening from the Nightmare of Zoos (No Voice Unheard), which we’ve excerpted here. Text © 2007 by Derrick Jensen. Photographs © 2007 by Karen Tweedy-Holmes.

— Ed.