IT probably should have been clear from the title of her doctoral thesis — “Patriarchal Power and the Pauperization of Women” — that Sister Louise Akers would eventually find herself in trouble with the Catholic Church. In 2009 Akers joined a long line of intelligent, articulate Catholics who have been officially silenced by Church leaders. Cincinnati archbishop Daniel Pilarczyk barred Akers from teaching or speaking in any institution related to his archdiocese, where she had served and taught for decades. His reason? She refused to publicly renounce her belief that women should be allowed to become priests.

Conservative Christians tend to get more media coverage, but there are many Christian progressives like Akers who serve their communities and work for social change. She has taught in high schools, colleges, and parishes. She’s also ministered to those on the margins of society — “the least of these,” in the words of Jesus — but she doesn’t just provide service or charity to them; she advocates for legislative changes to improve their lot.

Akers is a member of the Cincinnati Sisters of Charity, who take vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. Some reside in a common house, but many have their own apartments. They live simply, sharing possessions and patterning their lives after the founder of their order, Elizabeth Seton, the first American-born saint.

The daughter of a public-health nurse and a police officer, Akers came of age during the 1960s and was heavily influenced by the civil-rights movement and the Second Vatican Council, which increased the role of laypeople in the Church, did away with the Latin Mass, and generally brought Catholicism into the twentieth century. Her ministry is best summed up as “Everyone Welcome at the Table,” the title of her 2009 keynote address at the annual conference of Call to Action, a national organization that advocates for gay rights, women’s ordination, and the rights of clergy to marry. She shares her views online through her website, paradigmsshifting.org.

Akers, who turned seventy this year, has a master’s degree in theology and received her doctor of ministry from the Episcopal Divinity School in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She has served as the founding coordinator of Cincinnati’s Intercommunity Justice and Peace Center and as the social-concerns director of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious (LCWR). In 2006 she spoke at the Women’s Freedom Forum at the U.S. House of Representatives and participated in the fiftieth session of the UN Commission on the Status of Women. Her ministry has taken her to Malawi, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Mexico, the Czech Republic, Germany, Italy, Spain, France, Canada, and Cuba. At home in Ohio, Akers created Urban Plunge, an immersion program for suburbanites who’ve had little or no contact with inner-city residents, and Women Walk/Talk, which brings together urban African American women and suburban white women to address the problems of poverty, low-income housing, and domestic violence.

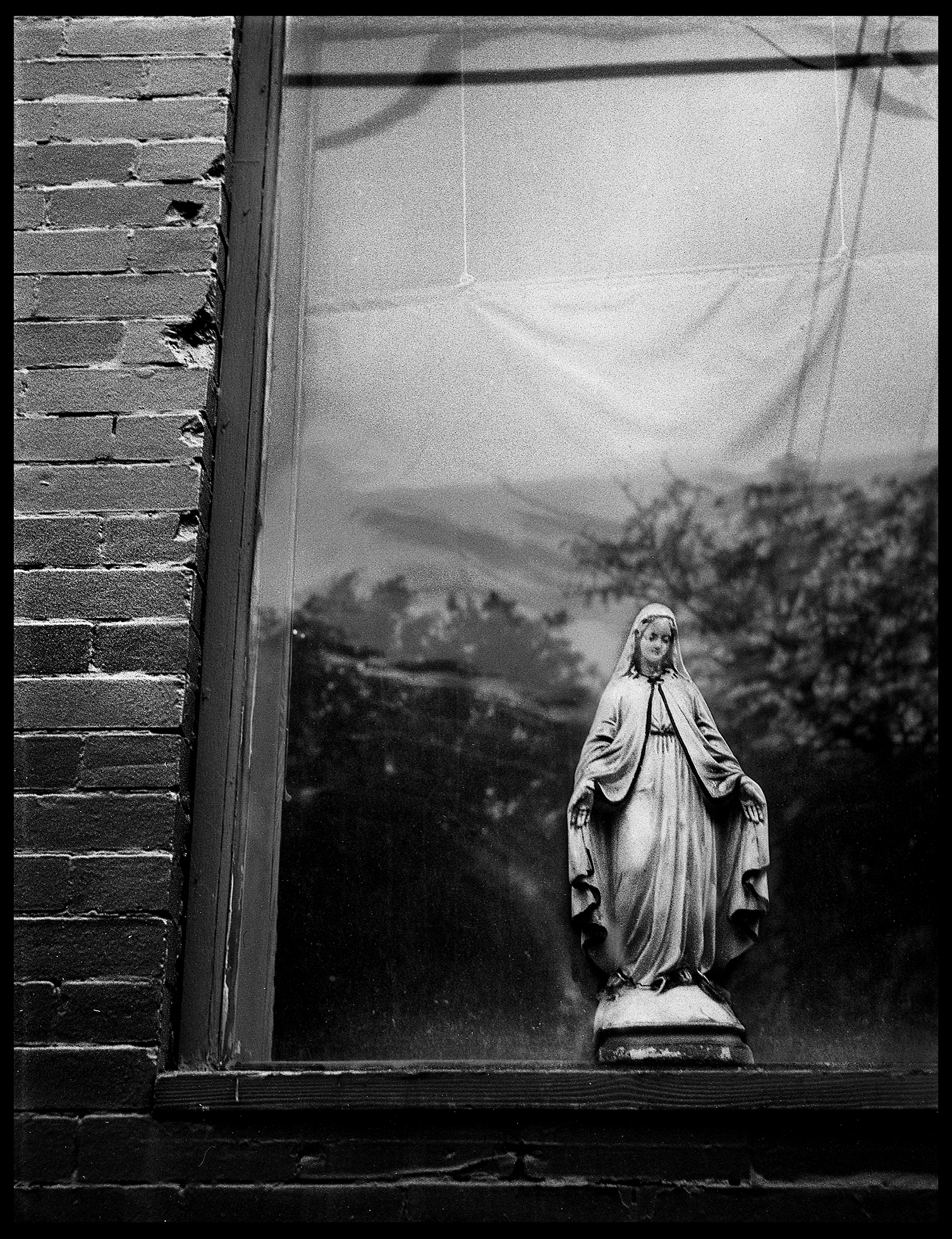

Akers lives in an apartment in a red-brick building in a working-class neighborhood. I met her there for two of three conversations we had. One wall of her dining room is covered with shelves of books and framed photos from her travels throughout the world. Around the time of our interview, Pope Benedict XVI resigned as head of the Roman Catholic Church and was replaced by Pope Francis. The last time a pope had resigned was six hundred years earlier.

With her bright eyes, quick smile, and easygoing manner, Akers doesn’t seem like the sort of person who’d pose a threat to the Catholic Church. As angry as she can get over injustice, she reserves her judgments for institutions, not individuals. At one point I asked how she walks the line between the dictates of her conscience and Catholic teachings.

“It’s not easy,” she said. “As a young person I didn’t see religious life in my future. I thought I would get married and have kids. But at the time that I joined the Sisters of Charity, I just felt it was what I was supposed to do — and I still feel that way. My spirituality has taken me places where I never thought I would go, including some that aren’t in accord with traditional Catholic doctrine.”

As I was leaving Akers’s apartment the first time, I noticed a stack of bumper stickers on a table: Subvert the dominant paradigm, they said. She had the same sticker on her car. When she first put it on the bumper, she said with a smile, a priest told her most people wouldn’t know what it meant. Akers said she wasn’t worried. She knew what it meant.

SISTER LOUISE AKERS

Lyghtel Rohrer: In 2009 you were “silenced” by Cincinnati archbishop Daniel Pilarczyk — that is, barred from teaching in his archdiocese, as you had done for decades. What was the reason?

Akers: I’d been teaching a course for religious educators when the subject of women’s ordination came up, and I presented both sides of the debate. One of my students thought that was outrageous, and she wrote to Archbishop Pilarczyk, saying I was a heretic. The archbishop sent me a copy of the two-page, single-spaced letter and told me I could respond to it or not, but if I did, he wanted to see my response. I replied honestly to the woman — with a copy to Pilarczyk — saying, among other things, that I supported women’s ordination.

My position on the issue was no secret. Every year on Ash Wednesday I participated in an alternative prayer service on the steps of Saint Peter in Chains Cathedral in Cincinnati, asking the Church to repent of the sin of sexism. Another time I cohosted a visit by Patricia Fresen from South Africa. She had been a Dominican sister and later had been ordained through an organization that ordains women priests in defiance of Church law. More than three hundred people came to hear her. I was interviewed by The Cincinnati Enquirer about her visit, and Pilarczyk was quoted in the same article, saying that the archdiocese had nothing to do with the event. So he knew where I stood.

After sending the letter, I met with Pilarczyk to follow up. He began by saying that I was supposed to be teaching doctrine, which is absolute, and not theology, which allows speculation and analysis. I wasn’t supposed to raise questions, in other words. I said I did teach doctrine, but that doctrine had evolved through a dialogue between the Church and theologians, and I was fostering a similar dialogue with my students. He then demanded I make a public statement that I had changed my mind and now agreed with the Church’s teaching against women’s ordination. I said I couldn’t do that; it would be a lie and would go against my conscience. That’s when he told me I would no longer be allowed to teach in any Church structure directly related to the archdiocese.

After the meeting I had lunch with my friend Judy Ball, who used to be editor of The Catholic Telegraph. She realized the significance of what had happened and wrote an article about it for the National Catholic Reporter. After the piece came out, the editor told me that it had received more responses than anything else they’d ever published. Many were negative, but overall people’s reactions have been supportive.

Lyghtel Rohrer: Does silencing dissent hurt the Church?

Akers: I think it does. Initially those being silenced were all men. It’s only more recently that women have spoken out enough to be silenced.

Silencing not only hurts the Church; it’s also not working. We’re not being silent, and more and more people are speaking up. The list is growing. Groups are forming. And the blame for the division within the Church is laid on the dissenters rather than on the inflexible leaders who refuse to recognize valid dissent.

The Vatican and the U.S. bishops see our emerging model as a threat to theirs. Our model is circular, whereas theirs is up-and-down. We feel that differences can enrich our faith; the Vatican feels that it owns the truth. I say we all have some truth, and let’s bring our truths together.

Lyghtel Rohrer: Would you say the Vatican has no interest in dialogue?

Akers: Its understanding of dialogue is that the Church leaders will talk and you will accept what they have to say, because they are the authorities. But look at the chaotic state of our world. For women and other marginalized people, the days of that kind of “dialogue” are disappearing.

Lyghtel Rohrer: What role have women traditionally played in the Catholic Church?

Akers: For most of its history, women have been seen as having a complementary role to that of men, not an equal one. In the early Church, women actively participated in religious rituals and served as deacons under the priests, but the writings of the Church fathers take a misogynistic view of women. Saint Jerome, for example, said that women are a “pathway to hell,” and Saint Augustine viewed women as intellectually inferior and as a moral threat to men. This view of women was consistent through the Middle Ages, when Thomas Aquinas wrote in Summa Theologica that women are “misbegotten males.”

When I first heard that in theology class, I expressed my disagreement, and the teacher — a young Dominican priest — said, “You don’t disagree with Thomas Aquinas.” I remember sitting there thinking, But I do. I couldn’t imagine how Aquinas had gotten the idea that women were inferior. I just couldn’t get over it. Of course, Aquinas was raised on the teachings of Augustine, who was raised on Aristotle, who was the original source of that misogynistic concept. Aquinas certainly wrote many wonderful things, but to think that he was the theologian in the Catholic Church until the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s is sad.

In the 1980s the U.S. bishops tried to write a pastoral letter — a public statement to laypersons and clergy — about women. In the first draft they said sexism was a sin, but that statement was eliminated by the Vatican. They went through four drafts, all rejected by the Vatican, before they finally shelved the letter. To this day no document exists on the role of women in the Church. You name the issue — racism, migrant workers, capital punishment, prison reform, war, climate change, immigration — and the U.S. bishops have written pastoral letters clearly identifying the Church’s stance. But not on women. They did come out against domestic violence, but that’s it.

Lyghtel Rohrer: What changes would you like to see in Church teachings?

Akers: One would be the Church’s stand on birth control, an issue that involves both women and men. In his 1968 encyclical on responsible parenthood, Pope Paul VI went against the majority of the commission that drafted the document and included a paragraph condemning contraception. To this day the Church still upholds that position, even though 98 percent of U.S. Catholic women under forty-five who have had sex say they have used birth control at some time in their lives. In places like Latin America and Africa — and, to a lesser extent, in the U.S. — contraception is an economic issue: women can’t escape poverty if they can’t control the number of children they have. The Second Vatican Council stated in 1965, for the first time in Church history, a twofold purpose of marriage: procreation and love between husband and wife. Each has equal importance. It seems to me that the use of contraceptives can enhance married couples’ relationships by freeing them to enjoy intimacy without the possibility of pregnancy.

I also have difficulty with mandatory celibacy. It’s one cause of the shrinking number of priests. Celibacy wasn’t a law of the Church until the twelfth century, when it was put in place to keep married priests from leaving their wealth to their children, rather than the Vatican.

Lyghtel Rohrer: Would you like the priesthood to be open to gays and lesbians?

Akers: Yes, I believe the priesthood should be open to all men and women who feel called to it, whether they be gay or straight. The U.S. bishops’ 1997 pastoral letter addresses the issue of homosexuality with the adage about loving the sinner but not the sin, which assumes that homosexual relationships are evil. When that document first came out, a lesbian student of mine was crushed. It was so hurtful to her. It also didn’t go over well with many parents of gays and lesbians. But people’s views are changing fast in this country. Homosexual relationships are gaining acceptance.

When my nephew Dave was thirty-six, he invited me to lunch. As we ate, he talked about his friends, and after naming each one, he’d say, “He’s gay.” Finally I asked, “Dave, are you gay?” For many years I’d thought he might be. His response was to burst into tears. I was the first family member he told.

Recently Dave asked if I remembered the name of the waiter who’d come over and offered him a napkin after he’d started crying. “His name was Jesus,” Dave said.

Sure, there continue to be challenges and difficulties for him, but I believe Dave’s sense of self has grown. His conservative parents have reversed their views because they love their son. Their acceptance has been amazing and inspirational.

Lyghtel Rohrer: The Church has a troubled relationship with human sexuality in general.

Akers: The traditional teachings of the Church don’t appreciate the value of sexuality. Cardinal Roger Mahony, who was involved in the major coverup of pedophile priests in Los Angeles, is quoted in a New York Times article as saying that he was “naive . . . about the full and lasting impact these horrible acts would have on the lives of those who were abused.” To me that speaks volumes about seminary training, or the lack thereof, on the subject of sexuality.

The Church needs to teach the inherent goodness of sexuality. Years ago it taught that even sexual intercourse between a married man and woman was evil. Now married sex is seen as an expression of the holiness of the union. But we are still a long ways from where we need to be. Rather than getting hung up on celibacy, Catholic priests and nuns, brothers and sisters, need to be free to choose the way of living that is the best expression of who we are. It’s not a matter of one way being better than the other. It’s that who we are shapes how we can be in loving relationships with other people and with the world.

Lyghtel Rohrer: Where do you stand on abortion?

Akers: The Church’s opposition to abortion is well-known. When giving presentations, I would often ask how many people knew the Church’s stance on abortion. All hands would go up. Then I would ask how many knew the Church’s position on capital punishment. A few hands would go up. I think the classic expression of the abortion stance was made by Archbishop Joseph Bernardin when he spoke at Fordham University in 1983. He coined the phrase a “consistent ethic of life,” which later became known as the “seamless garment.” If we revere life, he said, it follows that we need to uphold life from the womb to the tomb, whether on the issue of abortion, capital punishment, or war. Today we might add drone strikes.

Life is sacred, but I don’t think to be against abortion is automatically to be against choice. Nobody I know is pro-abortion. They are pro-choice. To me there is a difference. A woman who is poor and already has children and finds herself pregnant again may choose to have an abortion because she can’t take care of another child. I do not fault her for that.

So although I cannot say I am pro-abortion, I am pro-choice. I believe in allowing people to decide what is best for them in their particular circumstances, because their faith may be different from mine. I also believe there would be fewer abortions if we would provide contraception to all women and alleviate the conditions that make it difficult for them to care for the children they do conceive.

Lyghtel Rohrer: What about providing teenagers with birth control?

Akers: I personally do not support it. I realize many teens are sexually active — I believe our culture encourages them to be — but there are strong arguments against teen sexual activity, because of the negative emotional impact it can have. I think trusted, mature adults — parents, counselors, healthcare workers — need to be in on conversations with teens before they become sexually active.

The writings of the Church fathers take a misogynistic view of women. Saint Jerome, for example, said that women are a “pathway to hell,” and Saint Augustine viewed women as intellectually inferior and as a moral threat to men. This view of women was consistent through the Middle Ages, when Thomas Aquinas wrote in Summa Theologica that women are “misbegotten males.”

Lyghtel Rohrer: How does the Church justify positions, such as its opposition to contraception, that many Catholics disagree with or simply ignore?

Akers: I think it is built into the hierarchical structure. If we had a more inclusive Church — with married priests, women priests, gay and lesbian priests — Catholicism would have a different face.

The 2,500 bishops who gathered for the Second Vatican Council defined the Church first as “mystery” and second as the people of God. It wasn’t until the third chapter of their final draft that they dealt with the hierarchy. Many Catholics, priests included, not only embrace the idea of the Church as the people of God but also recognize a need for the Church to operate in a more participative fashion. We are not there yet.

Lyghtel Rohrer: What role should the Church play in helping to liberate women around the world?

Akers: Two-thirds of the poor people in the world today are female, so liberating women begins with economic justice. Catholic social teaching lays a strong foundation for what the Church calls the “preferential option for the poor,” which means we should put the poor’s needs first. The liberation-theology movement recognizes the terrible reality of poverty and class struggle and uses the gospel to advocate for social change. And of course Pope Francis has repeatedly shown in words and deeds his support for those living in poverty.

Lyghtel Rohrer: What is Catholic social teaching?

Akers: Catholic social teaching is one of the greatest gifts the Church has given us. It’s a collection of documents, encyclicals, and synod statements that address issues of justice, such as the rights of workers, the care of the environment, and the well-being of the poor. An estimated 15 million children in the U.S. are living in poverty. We are the richest nation on earth. That is a crime.

We think poverty is just the lack of assets and bargaining power, but it’s more. I used to have a bumper sticker that said, Poverty is violence. The U.S. bishops in 1974 talked about the violence toward people who live in poverty that occurs in boardrooms: “Lives sometimes are diminished and threatened not only in the streets of our cities, but also by decisions made in the halls of government, the boardrooms of corporations, and the courts of our land.” That’s from the U.S. bishops!

I recently heard biblical scholar Walter Brueggemann talk about the predatory economy versus the economics of compassion. It’s similar to what he writes about in his book The Prophetic Imagination, where he points out that our faith was founded by prophets who opposed injustice and oppression. A prophet, for Brueggemann, is an iconoclast who challenges revered institutions and proclaims them basically empty. Martin Luther King Jr. was a prophet who challenged the institution of racism, which was considered sacrosanct at the time.

Many women today are challenging the false god of patriarchy, saying, Enough already! We aren’t asking for a bigger piece of the pie. Our goal is to change the recipe. We want systemic change. People sometimes ask me, “Do we really want to go that far? Do we really want to say that?” When I hear this, I think of Jesuit activist Daniel Berrigan, who in the 1980s said, “I would like to be a middle-of-the-road Jesuit, but the times do not allow for it.”

Sometimes when I am speaking publicly, people who have problems with what I am saying describe it as “radical feminism.” It makes me smile when I hear that, because it’s redundant. All feminism is radical. It’s a radical shift away from patriarchy.

Lyghtel Rohrer: Are there limits to your liberalism? Are there parts of liberation theology, for example, that you don’t support?

Akers: I don’t think so. Some claim that liberation theology is really Marxism, because it acknowledges the class struggle, but I don’t see that recognition as a negative. I see that as naming what is happening. All liberation theologies — be they black, Latin, feminist, mujerista — begin with people’s lived experience.

Lyghtel Rohrer: What is mujerista?

Akers: Mujeristas are Latina women who want women’s rights but may not identify with U.S. feminism. Feminist theology in this country grew mostly out of the experience of white suburban women. Women of color have different lived experiences. Some African American women identify themselves as “womanists” — a word coined by author Alice Walker. But all these groups challenge the patriarchal system.

Lyghtel Rohrer: How do you define feminism?

Akers: I would start with the belief in the dignity and value of women, which implies equality with men. But there is more. Feminist movements all over the world have delivered radical critiques of our way of living. They name the root cause of women’s pain as patriarchy. According to Rosemary Radford Ruether, a pioneer in feminist theology, feminism challenges our hierarchical system of domination, where powerful men rule. It’s a system that has created wars, vast injustices, and ecological disasters, and the Catholic Church is one of the strongest remaining bastions of it.

Women’s issues are important not only to women; they’re issues that should concern everyone, in every discipline, every profession. When men really understand feminism, they see how empowering it is for them, too. It can free both genders from the boxes they are put in.

Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn’s Women Hold Up Half the Sky exhibit recently came to Cincinnati, and in it there’s a wonderful video of Goretti Nyabenda, a woman from Burundi, who was poverty-stricken, oppressed, and violently abused by her husband. Then she joined a solidarity group that gave her better opportunities, and she became a business owner and community counselor. After sixteen years of marriage, she says, she and her husband are finally communicating. Her husband used to treat her as if she were nothing, but now that she is the breadwinner, he respects her and sees her as a partner. Nyabenda probably wouldn’t call herself a “feminist,” but what has happened in her life is in part the result of feminism.

Sometimes when I am speaking publicly, people who have problems with what I am saying describe it as “radical feminism.” It makes me smile when I hear that, because it’s redundant. All feminism is radical. It’s a radical shift away from patriarchy.

Lyghtel Rohrer: Speaking of patriarchs, what were your thoughts when you heard that Pope Benedict XVI was resigning?

Akers: After my initial shock wore off, I thought about what a wrenching decision it must have been for a man so steeped in tradition to break six hundred years of it. I think that took a lot of courage. But I could also read between the lines of his statement and surmise that he no longer had the mental or physical capacity to meet the challenges of the Church today — and not just the scandals involving pedophilia and Vatican finances, but also the issue of women in the Church. Benedict has little credibility as far as women are concerned. His understanding of women, like that of many bishops, is based on misogyny.

But all people are multifaceted. Benedict does have a history, as a theologian and as pope, of speaking for those who are living in poverty. He has also spoken out against unbridled capitalism. I applaud him for that.

Lyghtel Rohrer: It’s interesting that Benedict has the courage to speak out against poverty but has been unable to see how empowering women lifts them and their families out of poverty.

Akers: If there could just be an open dialogue in the Church, instead of knee-jerk condemnation of dissenters, it would let in some fresh air. Church doctrine has evolved through history and sometimes changed to adapt to the times. But issues such as married clergy, ordained women, and homosexuality are so contentious that the Church’s response is simply not to talk about them, or to punish anyone who questions tradition.

Lyghtel Rohrer: What is your impression of Pope Francis?

Akers: He has been a surprise and continues to be on many levels. He has discarded some symbols of an exalted papacy by choosing simpler vestments and residing in a guesthouse at the Apostolic Palace, rather than the papal quarters. His recognition of women’s dignity bodes well for restoring the credibility of a Catholic Church that has been weighed down by crises. He washed the feet of two women on Holy Thursday. He spoke at Easter about women. Those are positive signs that the “good news,” the gospel, will be dominant during his tenure. But Francis elected to continue the investigation of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious [LCWR], which came under Vatican scrutiny in 2011 for presentations that were considered contrary to official Church teaching. That was a disappointment.

Lyghtel Rohrer: Have your beliefs always been integral to who you are, or did they evolve over a period of time or with a particular insight?

Akers: I think it’s been both evolution and insight. My father died when I was three, and I was raised by two strong Irish women: my grandmother Nellie McCann and my mother, Mary McCann Akers, who was a public-health nurse and a woman ahead of her time in many ways.

After I entered the Sisters of Charity in the early 1960s, I experienced a particular incident that was significant to my development: I was reading Our Part in the Mystical Body, by the Jesuit priest Daniel Lord, and it struck me that the mystical body was not a metaphor. We really are all part of the same body.

The Second Vatican Council was happening at the same time. I devoured the Church documents as they came out, especially the Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World. John F. Kennedy was the first Catholic president; Martin Luther King Jr. was leading the civil-rights movement; Cesar Chavez was leading the farmworkers. All this was happening while I was a novice sister.

Lyghtel Rohrer: And where did the rights of women come in?

Akers: There was the women’s movement, of course, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, but I don’t think I was initially conscious of it. As a public-health nurse, my mother was concerned about women who were poor. Sometimes I would go with her on her visits, or she would come home and tell my sister and me, “I met a little girl today, and she didn’t have a sweater,” or, “she didn’t have a doll.” My sister and I would look at each other and think, Uh-oh.

Lyghtel Rohrer: You were going to lose a sweater or a doll.

Akers: Yes. It’s not as if we had much, but Mom taught us to share what we did have. I often think of the effect her example had on me, in regard not only to women but also to race. I don’t remember this, because I was so small, but my mom told me the story of how my dad, who was a policeman, brought his partner home for dinner one night. His partner was a black man, and I was sitting on his lap and rubbing his hand. He smiled at me and said, “Honey, that doesn’t rub off. That’s me.” So I’m sure that had an impact. And one time, when I was in the fourth grade, Mom and I were walking down a narrow sidewalk in town, and an elderly black man coming toward us stepped off the sidewalk and tipped his hat as we passed. I asked my mom why he’d done that, and she said, “Because that’s what he thinks he’s supposed to do, because many white people say that’s what he’s supposed to do. But we know that’s not right.”

Lyghtel Rohrer: When did you come to believe in women’s ordination?

Akers: Initially I was much more concerned about the poor. Then in 1972 Ms. magazine began publishing. I asked the librarian in the inner-city, all-girls high school where I taught if we could subscribe to it. She said yes, but after the first few issues came, she approached me and said she was going to keep the magazine behind the desk, and I should let her know when I wanted the girls to read an article.

When I began developing courses on women’s history, some members of the faculty got upset. And this was an all-female faculty.

God is within me, and I am within God. I wrestle with that reality, and I’m in awe of it. We often talk about God being within us, but to say we are within God brings up a different image, as if we are in the womb of God.

Lyghtel Rohrer: Were you reading feminist literature at that point?

Akers: Oh, yes. Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique, for example. And I didn’t realize how unusual it was for a Catholic sister to be reading that. I just wanted to connect the dots. It’s all part of the same problem: structural injustice, in society and in the Church. Look at the similarities between the history of the LCWR and the life of the founder of the Sisters of Charity, Elizabeth Seton, a convert to Catholicism. She went up against the hierarchy of the institutional Church. She was a widow with five children. The more I learned about our history as a community, the more I saw us as strong feminists — even more so since the Vatican investigation. When Pat Farrell, a former LCWR president, said to representatives from the Vatican, “We will dialogue with you as equals,” I’m sure it shocked them.

Though the word feminist still scares many people, I think an increasing number of women are concluding that, deep down, they are feminists. Anne Wilson Schaef, who wrote about an emerging female consciousness in the 1980s, said to men, “To affirm my reality is not to deny you yours.” It was no different with black liberation. Black liberation may have denied white superiority or privilege, but it didn’t deny whites’ value; rather, it affirmed the value of black people.

Lyghtel Rohrer: What is your current role in the Church?

Akers: I can no longer teach in any institutions or groups related to the archdiocese of Cincinnati. Currently I am teaching our Sisters of Charity novices. I also write articles. I give radio and TV interviews. I speak in neutral locations, such as Protestant churches and coffeehouses. And I can still speak in other parts of the country and the world. Because of what happened with Pilarczyk, people frequently equate me with the issue of women in the Church, but I am not a one-issue person. For decades I have also been talking about poverty, racism, and war. What I strive to do is show how so many injustices can be traced back to patriarchal structures.

Lyghtel Rohrer: Do you feel constrained because you still are a part of the Catholic Church?

Akers: No. As I told Pilarczyk, I do teach doctrine, but I also raise questions. I’ve always made sure those taking my courses know what the doctrine is before we move on to the questions.

Lyghtel Rohrer: When I look at the Catholic Church today, it’s the women who give me hope. I know there are good priests, but you sisters are so far ahead of them.

Akers: I believe that’s why the Vatican and the bishops are challenging us. They feel threatened. But hope and change are in the air with Pope Francis.

Over the years I would often hear, “Why are you doing this?” Back in the 1960s it was fine for me to work with migrant farmworkers and be an advocate for social services, but not to walk the picket line. That was “no place for a sister.” People are comfortable with sisters providing services but not with sisters working for systemic change. I’ve always tried to do both, because I think systemic change enables marginalized people to transform their lives.

In the process I am transformed, too. Throughout my life my experiences with people — whether they be migrants, African Americans, or women in poverty — have changed me. People and their suffering and celebrations and the relationships you form with them — that’s what transforms us.

Lyghtel Rohrer: How have you been transformed?

Akers: The transformation is ongoing, but when I think about who I am today and who I was fifty years ago, I would say my spirituality is different. My image of God is different. How I relate to people is different. And that’s a challenge for Catholics, because if you have a different sense of spirituality, you become persona non grata as far as the traditional Church is concerned.

Lyghtel Rohrer: You said your image of God has changed. How?

Akers: My understanding of women’s reality has affected it. Now, when I address God, I frequently address Sophia, the female embodiment of God’s wisdom.

I worked hard to imagine a feminine God at first. For a long time I couldn’t do it. It’s important for me to remember that, because some people can never do it. A feminine God, a masculine God — God is beyond all that.

My prayer is different, too. I don’t pray to a God out there. God is within me, and I am within God. I wrestle with that reality, and I’m in awe of it. We often talk about God being within us, but to say we are within God brings up a different image, as if we are in the womb of God.

When I was a novice sister, I read a book by the great twentieth-century theologian Karl Rahner, who said that Jesus is identified as the Son of God because his humanity was a complete response to the divinity within him. Rahner said we are all sons and daughters of God. The degree to which we respond to the God within ourselves reveals our divinity. It’s similar to what Augustine said 1,600 years ago: that the glory of God is man fully alive. Of course, today we would say the glory of God is people fully alive.

Lyghtel Rohrer: In other words, it is in becoming fully human that our true divinity is revealed?

Akers: Yes. When I was a young woman preparing to become a sister, the other novices and I weren’t supposed to say, “Hello,” or, “How are you?” when we met each other. We were supposed to say, “Praise be to Jesus.” And the other person would say, “Amen.” At the time I thought, Why are we saying this? It was such a hard thing to do. But now I see that “Praise be to Jesus” means “I am recognizing the God within you.”

Lyghtel Rohrer: Over the centuries the Church has accommodated itself to the norms of culture. It’s done so with practices that are the antithesis of the Christian message — such as war, slavery, and racism — but it has also accommodated positive cultural developments. For example, there are churches that are accommodating LGBTQ communities. How does a church distinguish between just and unjust accommodations? What is the gauge?

Akers: Different people have different gauges, but the four basic principles I try to uphold are the value and dignity of the person; the common good; solidarity with those who live in poverty or are otherwise marginalized; and the sacredness of earth. And I rely on Scripture. One of my favorite passages is Luke 4, where Jesus begins his public ministry by opening the scroll to Isaiah and saying, This is why I’m here: to let the prisoners go free, to give sight to the blind, to help those who are oppressed. And recently a friend sent me this quote from the Talmud: “Do not be daunted by the enormity of the world’s grief. Do justly, now. Love mercy, now. Walk humbly, now. You are not obligated to complete the work, but neither are you free to abandon it.”

These Scriptures have been the gauges by which I have tried to live.

Lyghtel Rohrer: Are there specific things we can do to make a difference?

Akers: Martin Luther King Jr. once said that true compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar; it’s recognizing the edifice that produced the beggar. But acts of mercy are still a good starting point. If people perform acts of mercy or service long enough, they begin to ask questions such as “Why are there so many homeless people?” or “Why does the food bank need so many donations?” Eventually they begin to look at the systems that create conditions of poverty.

So even though the best way to change the system is through legislation, I try to get people involved in hands-on service. Middle-class Americans need direct contact with people who are poor or marginalized. One man who got involved told me that all his life he’d read about poverty, but this was the first time he’d talked to someone who was poor. It changed him. He went from no involvement to being on his parish’s justice commission to becoming the chairperson of it, all because he’d had that direct experience with people living in poverty. Not that donating money isn’t good. You just want to target your money to those groups that are really making a difference, such as Bread for the World, the Catholic Campaign for Human Development, and Call to Action — all justice organizations that advocate for human rights.

Lyghtel Rohrer: The institutional Church doesn’t always live up to your ideals. Why do you remain a part of it?

Akers: Since Pilarczyk’s action, I have thought of leaving, but I haven’t. There is something within me that calls me to stay, but in a different way than when I first entered the community.

Two events stand out for me in regard to this decision: The first was in 1963, when I asked my director if two other sisters and I could go to the March on Washington with Martin Luther King Jr. She referred me to our mother superior, who referred me to the archbishop. The answer came back no. We were to go to church instead and pray that there would be no violence. I remember saying, “But, Sister, what is the Church? Where is the Church?” And she told me we weren’t going to have that conversation. But we needed to have it. Fifty years later I think we still need to have it.

The second came when I was in Nicaragua in the 1980s, and Pope John Paul II came to visit the country. The day before his visit there had been a funeral for seventeen teenage coffee pickers. The boys had been killed by the Contras, antigovernment forces that the U.S., under the Reagan administration, was supporting. The day after we stood with the families, our hands on the coffins of their sons, we gathered again for a Mass with the pope. The mothers asked that the pope pray for their dead sons, and he refused. We heard later that an advisor had told the pope it would be too political to pray for these young men. The crowd that had gathered for the Mass reacted strongly when it realized that the pope was refusing to pray for their native sons. The mothers were holding up photographs of their boys, crying, “Presente!” and at one point the pope was yelling, “Silencio!” It was awful.

The next day, all over Central America, Catholics gathered to talk about what had happened. I asked a woman if she thought many people would leave the Church because of how the pope had responded. She looked at me strangely. I thought it was because my Spanish was so awful, so I had another sister translate for me. The woman still appeared confused. Then she said, “Leave the Church? We are the Church.” And I thought to myself, Louise, how many years have you said to high-school students, “Girls, we are the Church”? But it wasn’t until that moment, hearing the same message from this woman whose name I didn’t even know, that I finally got it. I will never forget her.

Lyghtel Rohrer: And that’s why you’re still part of the Church?

Akers: Exactly. When people say, “If you’re so dissatisfied, then leave,” I say, “Leave what? Myself?” It’s a struggle to continue on my own terms, but I do believe that we are the Church. The people of God: that’s us.