Last night I dreamed I was a Chinese man who worked in a nuclear power plant. The plant leaked radiation, and I spoke out about it and was denounced by the authorities. At home, my mother looked at me coldly and said that I was no longer her son. My father was sympathetic, but what could he do? My mother ruled the roost. I knew I was on my own: no job, no family.

I walked outside, into a bleak rural landscape — smooth, undulating slate blue hills against a flat khaki sky, as in a painting. The day was overcast and cold. I walked to the plant to tell my one friend — a man I’d known since childhood — about the radiation leak. We stood just outside the fence, on a rutted, unpaved road that wound through a field of sand and disappeared over a rise. I told him people would soon begin to fall ill. He listened, but what could he do? He had a wife and son, and needed the job.

The shift ended, and workers poured through the gates, all dressed as we were, in coarsely woven khaki jackets and slate blue trousers. They looked at me hatefully, though some knew the danger we were in. One woman spat on the ground near my feet. They walked in silence through the field of sand. When the last of them had passed, I turned to my friend, but he was gone, swept up in the crowd. One by one they disappeared over the rise.

I stood for a moment outside the gates, uncertain what to do next. In the fading light, a slight wind stirred the sand. Ash drifted out of the sky and settled on my clothing and on the palms of my outstretched hands. Though frightened, I knew that, in some real and permanent way, I had been given my freedom. My new life had begun.

I think a lot about dreams. It’s sometimes hard to tell which are merely the detritus of daily life, and which might be longing, or even prophecy. For years I often dreamed of a man breaking into my house through the front door. Most of the dream concerned the scattered, split-second decisions I had to make about where to run and how to save myself and whoever was home with me — usually my son, Will, though sometimes my deceased father.

The intruder always carried some weapon, often a knife. Instead of riding a black horse or a motorcycle, my Death stepped stealthily through the door. I watched from upstairs as he closed the door quietly and moved off in search of me, in the wrong direction, allowing me a few valuable moments — to act, to escape, to do something. In the worst variation of the dream, I turned from the top of the stairs and saw my father in one room, my son in another. I could go to only one of them. Though my father was dead, he seemed as real and vulnerable as my young son playing with toys on his bedroom floor. Before making the decision, I woke, heart pounding.

The winter that my son was ten, just after the Soviet Union collapsed, we lived in Ukraine, a block from the university where my husband lectured in American literature. One afternoon when Will and I were alone, a man started kicking the door of our first-floor apartment. We soon realized that he wasn’t a lost drunk, but someone trying to break in. Will ran to the living room, hid my laptop under the sofa, and locked the second deadbolt on his way into the kitchen. I phoned my husband as I cleared off the kitchen windowsill and unsealed the sash. Just as I opened the window, the door gave way, and the man appeared at the end of the dark hall, holding something: a pry bar or an iron pipe that flashed in the split second before Will and I jumped to safety.

Before that close call, I’d dismissed the recurring breaking-and-entering dream as proof of my neurosis. After that, it felt more like a premonition.

My mother used to say, “Never tell your dream before breakfast, or it will come true,” which suggests that dreams are never pleasant. Even a seemingly innocuous dream may hold a hidden trap of the “be careful what you wish for” variety. Perhaps this morning, if I tell my dream about the Chinese nuclear plant before I eat, the metaphor crouching inside it will be released. I’m a fair-skinned, blue-eyed woman who has never been to China. And yet I saw the world clearly through this Chinese man’s eyes, experienced sensations inside his body, became him completely. As him, I belonged to a family of strangers, was disowned by a mother with whom I had a long and complicated relationship — what else could explain her behavior? I was completely aware of my best friend’s life, though in the dream we never discussed it. I walked easily through the landscape, knowing I’d been born there, though no one ever said so. They didn’t need to, any more than they needed to tell me I was male and Chinese, or to point out that, by one defiant act, I had altered my life forever.

My actual birth took place in an army hospital in Georgia. On the military bases of my childhood, everything — buildings, vehicles, desks, walls, uniforms — came in one of two colors: khaki or olive drab. Conformity and order won the highest praise. A good soldier went where he was sent and did what he was told, and my father was a good soldier. A glance at his uniform revealed his whole life: nameplate, rank, division patch, hash marks, ribbons representing honors and awards. He served in Iwo Jima, Saigon, Pusan, Munich, Hollywood, Louisiana, and wherever else the army sent him. He re-upped, he was a lifer, and when he was nearly dead, he was medevacked home. In some small way, he made his mark on history.

When we say something is “history,” we mean that it’s over and done with, of no further consequence. And yet our history provides the warp into which all the other threads are woven. My military upbringing — my military history, if you will — is invisible, but fundamental to who I’ve become. The people in my dream of China arrived with their personal histories intricately constructed, so it makes sense that they departed the dream, too, with their histories intact. My dream mother may still be weeping in her room, head in hands, regretting the hard words she spoke to me, while my real mother sleeps connected to an oxygen tank on one half of a double bed in Louisiana. While I sit at the breakfast table, my Chinese self may be standing on a road he’ll wander — perhaps for years — until I dream of him again. Or perhaps by dreaming of him, I released him into a new life. The great feeling of freedom that came to him — to me — at the end of the dream felt like release. Still, the freedom I felt may have come from being lifted out of the dream, back into my own life, my own body.

Though Will is nearly twenty, tall and bearded, I sometimes dream that he’s still a baby. I hold the solid weight of his small body, smell his baby smell, stroke the smooth skin of his face and hands. Long after my son is a father himself, in my dreams he’ll still occasionally be an infant in my arms. My father, who died when I was a teenager, appears in dreams as he did when I last saw him, while I continue to age. Will he be surprised when one night I face him looking more like his mother than his daughter?

In my dreams of my father, we’re both perfectly aware that he’s dead, but he still drives me to the airport or sits at my desk using my computer, as if he were on leave from his new duty station in the afterlife. I’m always pleased to see him, grateful that he’s been given back to me for the duration of the dream. Still, I wonder if he really is my father, or only a manifestation of my need. He’s replaced my husband at the wheel of our car for a reason. That he sits at my desk, typing comfortably on a machine that didn’t exist in his lifetime, says something about how I see myself. The pleasant reunion is really a discovery about my adult life.

Once, I dreamed of my father as he was before my birth. My husband and I, in street clothes, stopped to talk to my young family on the beach. The narrow strand I dreamed us on was hemmed in on one side by the dark, roiling ocean, on the other by a wall of fog. My mother looked pretty and plump in a black bathing suit, but her demeanor was chilly, and she seemed suspicious of my interest in her family. My older sister sat in the shallows, a toddler playing with a plastic bucket, while my brother worked furiously on a sand castle, digging deep moats and building turrets. My father, barely thirty, thin and awkward in baggy brown trunks, seemed glad that I had stopped to talk. Here was a man who read the encyclopedia for kicks and wrote fiction and essays in his spare time. He was at the beach with his family and, like any other World War II vet, glad to be alive and back home.

Gradually I realized that he was trying to impress me, and I had a sudden out-of-body view of us standing together: my family in bathing suits, younger than I ever knew them, and I in my forties, wearing a crisp white shirt tucked into tailored khakis — an outfit I would never wear in real life. My heart felt ready to break. I wanted to explain that no barriers divided us, that I was theirs, their own flesh and blood, but the rules of the dream forbade it. And yet it was my dream. I was the one who made up the rules. The barriers existed only because I had created them.

“It seemed so real,” people say, with a kind of wonder, when they talk about their dreams. When I bring my dead father back for a trip to the airport or a chat on the beach, or return my college-age son to his infancy, it’s as if I’ve walked into their ongoing lives, not memories in which they wait around for my subconscious to write the script. My father has dimension, solidity, a familiar smell, certain mannerisms and turns of expression that, after so many years without him, I sometimes forget in my waking life. These dreams seem the hardest to wake from, and when I do wake, it’s with an ache in my chest for what I leave behind. I want to bring my baby son back with me, dandle him on my knee as I sit at the table with my father, my husband, my grown son. It’s not that I want time to stop, but that I want the different stages of my life to exist simultaneously, like chapters in a novel. I want to flip back to the start and take covert glances at the end, to identify motifs I might otherwise miss.

Milan Kundera wrote, “Memory does not make films; it makes photographs.” But dreams make films, taking the still moments of memory and infusing them with breath, air, and motion, augmenting them with music, the written word. Recently, I dreamed that my husband and I rented a large room in an old building in Moscow, where we’ve never been. The tall French windows were open, and long white curtains billowed in the summer breeze. Street noise filtered in, along with the familiar gray light of dreams. We sat in shabby upholstered chairs near the window, discussing something we’d just learned: that Chekhov had once lived in this room.

As we looked through the gloom at the blank wall opposite, a narrow iron bed slowly took shape against it. Beside the bed, a small, dark wood table held an array of medicine bottles, a bottle of ink, a carafe of water. Chekhov himself materialized on the bed: head propped on pillows, knees drawn up under the white blanket, a wooden writing board balanced across his thighs. His white nightshirt was open at the throat, and he wore a pince-nez.

Ignoring us, Chekhov wrote with intense concentration, stopping occasionally to dip his pen into the bottle of ink. We watched him in silence, fully believing that he was in the room with us. We heard the scratch of his pen, the rustle of the paper, the clink of the metal nib against the glass jar of ink. The sound of his breath came to us, and the smell of his body in the warm evening. Once, he coughed slightly and cleared his throat. He was as real in that room as we were, and whether we had suddenly appeared in his room or he had suddenly appeared in ours, an intense intimacy held the three of us in its grip.

The next morning, I pulled from the shelf a biography of Chekhov that I’d read years earlier. In a photograph, I saw that the room of which I’d dreamed was Chekhov’s bedroom in Yalta.

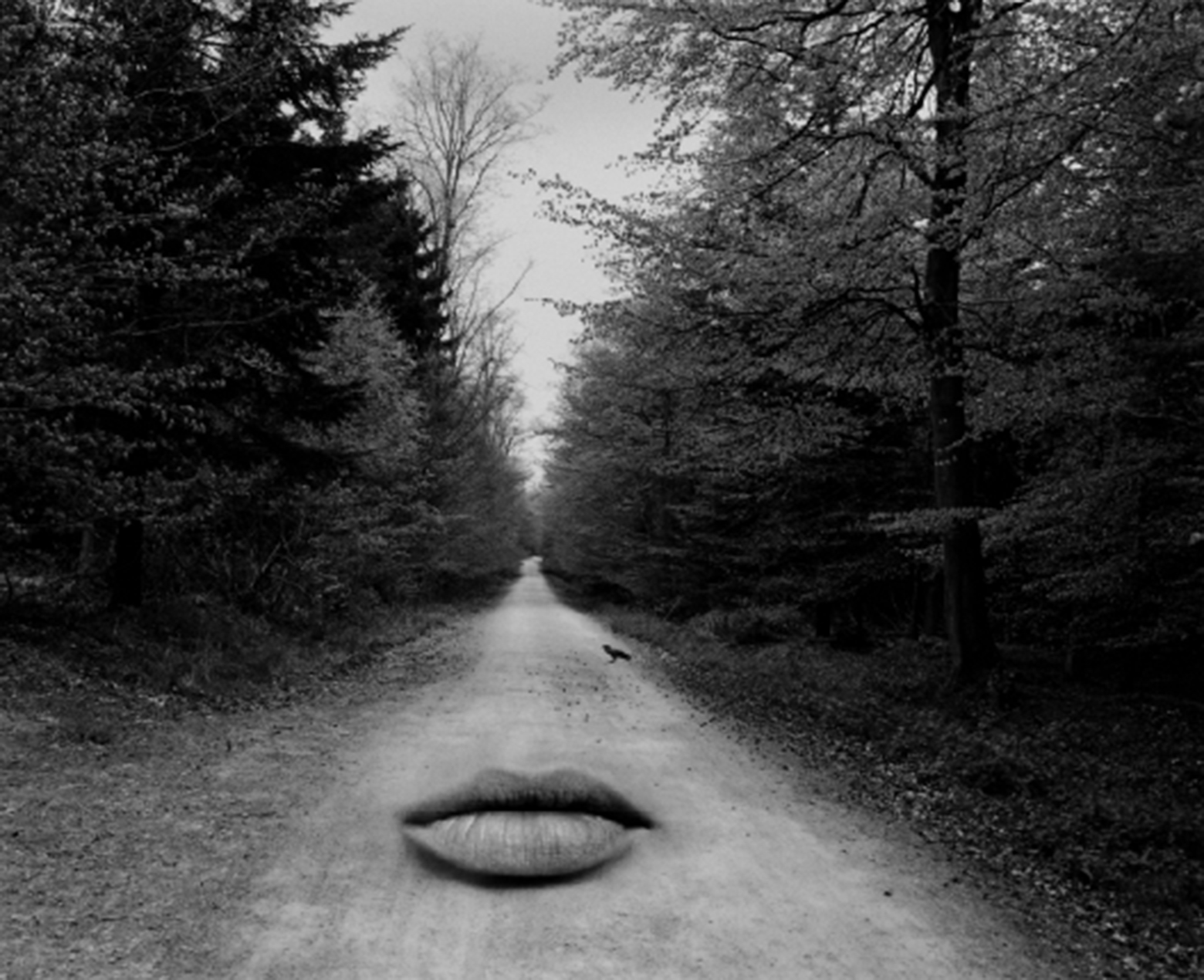

Light is part of what separates dream from real memory. My dreams most often happen in twilight, the blue-gray hour that is not being, but becoming. In life, such light lasts a few minutes, twice a day, but dreams unfold in suspended time: days might pass while the blue edge of dusk seeps from the woods, towing darkness like a great wing over the field.

As a child, I was sometimes afraid that I was being dreamed by someone else, that I had no actual substance and no control over what happened to me. Because I had experienced the sensation of dreaming for hours, only to wake and find that I’d taken a short nap, I reasoned that what seemed like my life might actually be a few minutes of someone else’s sleep.

Another childhood theory of mine was that all dreams took place in the same world. I was the star of my own dreams, but if people I’d never seen in life could appear in my dreams, perhaps I played a similar bit part in the dreams of strangers. The rules of this dream world were quirky, but somehow I always knew them. I was liable to do anything: walk to school naked, set fire to my sister. My house might belong to somebody else, or I might live in a house I’d never seen. Knowing that I was having a dream didn’t automatically allow me to escape it. But if I fell off a bridge, I always woke before I hit bottom.

I was very young when my mother explained falling in dreams: you had to wake before you hit; otherwise you’d have a heart attack and die from the shock. I knew from eavesdropping on adults that people did die in their sleep — that this was, in fact, the preferred way to die. To me, death arriving while you were asleep seemed like a dirty trick, a bait-and-switch. I was frightened at the prospect of being lured into the arms of sleep, only to be ferried off to the land of permanent bliss. At bedtime I recited the prayer my mother had taught me: “If I should die before I wake . . .” But I didn’t want the Lord to take my soul. I didn’t want surprises. I wanted to see death coming. I wanted a running start.

When I was fifteen, my father went to Vietnam. While he lived in Saigon, my life went on as usual. We were a military family, used to my father’s absence or the possibility of his absence. I read his letters, full of news about a place that never quite seemed real, and I occasionally answered with letters of my own. I learned to drive because my mother couldn’t, and I became the family chauffeur. When he left for Vietnam, I never doubted that my father would return, and he did. Then, four years later, under the relentless white sky of a July noon, while mowing the lawn of our house in Louisiana, he died of a heart attack.

My earliest dream about my father is one I had so often that its memory is more vivid than those of my early childhood: My father drives along the highway in our big 1954 Buick Special, which I loved in real life for its egg-yolk color. He’s in uniform, his summer “pinks” of khaki gabardine. His crew cut gleams with Butch Wax, and his nicotine-stained fingers lightly guide the wheel. My mother rides shotgun, and I’m standing on the floorboard in back, elbows resting on the front seat and chin propped on my hands. My parents talk, and the air grows hazy with the blue smoke of their cigarettes.

Dusk is coming on as we speed along the highway and up a gradual rise that leads to a bridge over the river. No cars approach from the other side. Realizing that ours is the only car on the road, I fidget a little with worry, but my parents keep talking calmly. I’ve been scolded so often for interrupting — my mother’s nickname for me is “Buttinski” — that I bite my bottom lip to stop myself from speaking. I stand rigid, watching and waiting, hoping that all my instincts are wrong and that nothing will happen except that we’ll cross the bridge and get to wherever we’re going. I look out the side window and see a thin metal guardrail separating us from the wide, dark river. The colors of the landscape are flat, as in a primitive painting, and unnatural, as in the light before a storm: chartreuse trees along the bank, slate sky, and whitecaps streaking the river’s black surface. My father lights another cigarette, and my mother yawns, hand covering her mouth. At the bridge’s summit, the pavement ends. After that, I see nothing but a long span of air above the water.

One evening when Will was a toddler, he used colored wooden blocks to construct an elaborate structure in the center of his room. Before bed, he put away his toys but left the blocks arranged, seemingly deliberately. I didn’t move them. The next morning, Will disassembled the structure and put the blocks back in their plastic bin. He did the same thing the following night. After a couple of nights of this, I asked what he was building. “It’s something I’m working on,” he said, brow furrowed.

I waited several more nights before I asked again. This time he looked soberly at the blocks and said, “A temple to my nightmares.”

He’d never spoken of nightmares before. Whenever he woke in the night, he called out in a languid singsong until I appeared in his room, but he didn’t cry or seem frightened, and in the morning when I asked, “Did you have sweet dreams?” he usually didn’t remember. Though my husband and I had strong spiritual lives, we didn’t attend religious services. We didn’t watch television, and the one time we took Will to a movie, he fell asleep during the previews and woke two hours later as his father carried him into the parking lot. In the books we read to him, there were no temples, no nightmares. Will’s belief that a structure might appease his bad dreams seemed to come from his own imagination.

Placing the blocks carefully, he explained that on the nights he built the temple, his dreams were good. He pointed to a space between two red blocks. “The nightmare goes in here,” he said, “and can’t get out.”

I wondered if this was how ancient religions began, with a troubled dreamer trying to make sense of the journeys of sleep. The dream world seemed strange, and even dangerous. The mound of rocks stacked outside the cave became a rough altar, then an enclosure. If the dreamer asked nicely, dreams were sweet — proof that someone else controlled the land of dreams.

Will glanced at me sitting beside him on the floor, then back at his temple. “I do it like this,” he explained. “The nightmare goes inside.” He barred the opening between the red blocks with a blue block. “Snap! I shut the door.” He paused for dramatic effect. “After a while, the nightmare just goes to sleep.”

“What happens in the morning?” I asked.

He cocked his head and studied his handiwork. “In the morning I let it out, and it runs off into the forest,” he said.

I saw then what he must have seen: the nightmare galloping into the morning dusk, hooves clattering, red mane flying. As the woods brightened, the dream slipped deftly between the trees, headed for the other side.