Ina May Gaskin is sometimes referred to as the “midwife of modern midwifery” because of the role she’s played in the rebirth of that profession in the United States.

Midwives, who are trained to assist with pregnancy, labor, and postpartum care, were once common in this country, but the profession was virtually eliminated in the early twentieth century and replaced by obstetrics. When Gaskin began performing midwife duties in the early 1970s, only a handful of U.S. hospitals employed nurse-midwives as birth attendants. Today about 10 percent of births are attended by midwives — either certified nurse-midwives, who mainly work in hospitals and birth centers, or certified professional midwives, like Gaskin, who attend births in homes or birth centers.

Gaskin practices at the Farm Midwifery Center in southern Tennessee. The Farm, an intentional cooperative community, was established in 1971 by Ina May’s husband, Stephen Gaskin, who had come to fame in San Francisco in the late sixties through his weekly lectures on spirituality and social-justice issues, called “Monday Night Class.” In 1970 he went on the road for a lecture tour and allowed more than two hundred young people to accompany him in a caravan of school buses and trucks converted into campers. Nine births took place in the caravan, with Ina May acting as midwife — since she was, at thirty, older than most of them, and a mother. A Rhode Island obstetrician provided her and some of the other women with a seminar in emergency childbirth measures, an obstetrics handbook, and supplies. Once the lecture tour had ended, most of the group pooled their money to buy land in Tennessee and start the Farm.

Gaskin soon accepted the role as her vocation and, with her friend and midwife partner Pamela Hunt, began to study natural childbirth. They got their training on the job, with some help from mentor physicians who had experience assisting in home births for a large Old Order Amish community in the area. Meanwhile the Farm was reaching out to the rest of the world through its burgeoning aid organization Plenty. In 1976 an earthquake struck Guatemala, killing more than twenty thousand people and leaving a million more homeless. Plenty volunteers traveled there to help, and Ina May made contact with the local midwives. From them she learned a procedure for dealing with a birth complication known as “shoulder dystocia.” She brought this lifesaving knowledge back to the U.S., where it became known as the “Gaskin maneuver,” the first obstetrical maneuver to be named after a midwife. She believes that midwives in the developing world possess wisdom and practical skills worthy of being studied in more-affluent countries.

The Farm has undergone many changes in its forty-year history, but the midwifery center has been a mainstay, providing prenatal care, doula services (nonmedical assistance and support for women in labor), birthing facilities, in-hospital services, postpartum care, and health education for women. The Center is known for low rates of medical intervention, morbidity (illness or injury associated with pregnancy and childbirth), and mortality and has become a touchstone of how safe birth can be.

Gaskin is the author of four books on natural childbirth. Her most recent, Birth Matters: A Midwife’s Manifesta, focuses on the sharp rise in cesarean births, or C-sections, in the U.S. and the corresponding rise in the percentage of women who die from birth-related causes, referred to as the “maternal mortality rate.” To draw attention to the increase in maternal mortality over the last two decades, Gaskin began the Safe Motherhood Quilt Project (www.rememberthemothers.org). Like the AIDS quilt, it’s a collection of hand-sewn memorials, in this case honoring women who have died of pregnancy-related causes during the past thirty years.

For twenty-two years Gaskin published a quarterly titled Birth Gazette. She was president of Midwives Alliance of North America from 1996 to 2002, and a former director at the World Health Organization called Gaskin the “most important person in maternity care in North America.” In 2011 she was a recipient of the Right Livelihood Award, also known as the “alternative Nobel prize.” She travels widely to lecture on the Gaskin maneuver and other matters pertaining to childbirth. Her message, at home and abroad, is that the most important “technology” for a woman in labor is patience, kindness, and encouragement.

I traveled to the Farm on a hot day in mid-July and sat down with Gaskin at her dining-room table in the comfortable, book-cluttered house she shares with Stephen. Two filmmakers were there making a documentary about her, and they set up their cameras to film part of the interview. Stephen stood in the kitchen, tall and thin, with a long white ponytail and a beatific smile. “People ask me if it bothers me now that Ina May is more famous than I am,” he said as he handed me a glass of water. “I answer, No! I am happy she is keeping our light lit on the international board.”

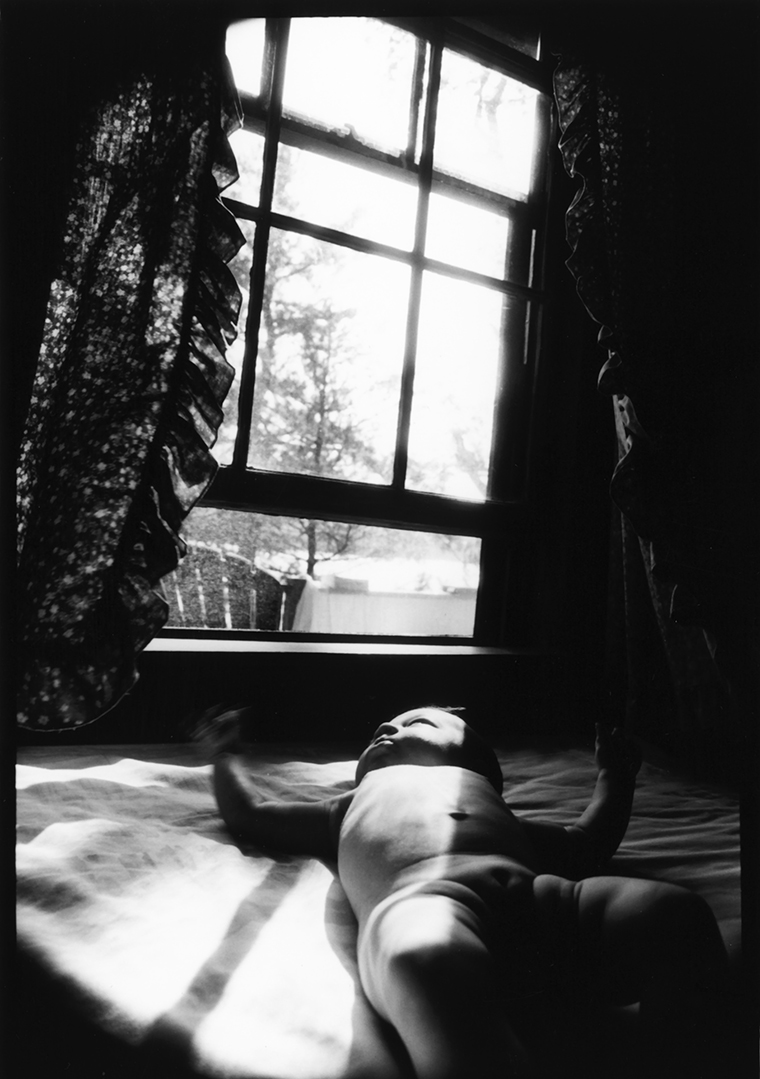

After we’d talked for an hour, a thunderstorm broke, and we made a dash for our vehicles and drove down to the clinic. The documentarians filmed Gaskin as she talked with Kristina, a young woman who was due to deliver any day, and her husband, Seth. The walls were decorated with pictures of wise-eyed babies, and the atmosphere was one of cheerful anticipation.

INA MAY GASKIN

MacEnulty: One of my friends told me that when he and his wife decided to have a home birth, he was roundly criticized by family members, who said he was being irresponsible and endangering the health of the baby.

Gaskin: There is an assumption that we humans are inferior to the other five thousand or so species of mammals in our ability to give birth to our young. I have always found it hard to accept this notion, probably because my father was a farmer for years. Those who are used to the birth ways of other mammals know that it is easy to cause complications during labor by disturbing the mother. If we put horses, goats, and cows through the restrictions and indignities that most laboring women in U.S. hospitals are routinely subjected to, the animals would surely have as many complications as we do. The astonishing thing to me is that we have come to believe that our human bodies are not as well designed for birth as other mammals’ are. Really it’s our brains that can pose problems: we alone among mammals have the ability to scare and confuse ourselves about birth.

MacEnulty: How did you become an advocate for midwives and natural childbirth? Weren’t you an English major?

Gaskin: Yes, and after I got my master’s degree, I joined the Peace Corps. But I was always interested in birth and birth stories. I had a horrific hospital birth — a mandatory and unnecessary forceps delivery — in the 1960s, and I knew there had to be a better way. Eventually I began hearing stories of natural birth, and they sounded beautiful and very different from the experience I’d had in the hospital. I set out to learn about it, and it became a calling.

MacEnulty: Your earlier books — Spiritual Midwifery, Ina May’s Guide to Childbirth, and Ina May’s Guide to Breastfeeding — could be characterized as how-to manuals, but your new book, Birth Matters, is subtitled A Midwife’s Manifesta. Why the urgency?

Gaskin: The urgency arises from the fact that we in the U.S. are in danger of destroying both obstetrics and midwifery in favor of all births being surgical operations. We know from the example of private hospitals in Brazil how far this trend can go — many of those hospitals have C-section rates that exceed 95 percent. It’s important to realize that Brazil has a relatively high maternal death rate — higher than ours. If we’re going to imitate any country’s maternity care, we should copy a country with better outcomes than ours.

My partners and I — and countless other midwives — know that, under the right circumstances, births can be safely handled with a minimum of C-sections. We have been able to attend some three thousand births, including breech [when the baby enters the birth canal buttocks first] and twin births, over the last forty years, and our C-section rate is 1.7 percent. There were only two C-sections in our first four hundred births. If these statistics are possible for us, they are possible for others. To accomplish this, we had to make sure that pregnant women had good nutrition and a healthy amount of exercise, and we needed to do everything we could to reduce the amount of fear surrounding birth by demystifying the process. All of these measures together have made the good outcomes at the Farm Midwifery Center possible.

MacEnulty: But aren’t there times when a C-section is the safest option for a woman — for example, a woman with small hips and a ten-pound baby?

Gaskin: Of course there are situations when a C-section is necessary. It may be that the baby gets into a poor position, or, rarely, the placenta might start to detach from the uterus before the baby is born or plant itself right over the cervix. The latter complication happens more often in women who have had previous C-sections.

But my partners and I have found that C-sections are very rarely necessary because of a mismatch in size between the woman and her baby. Having helped a number of women with what appear outwardly to be small hips give birth vaginally to ten-pound babies, I know that appearances can be deceiving. I have encountered fewer than ten cases out of three thousand in which the baby was actually too large to fit through the maternal pelvis. It happens most often with diabetic women, whose babies can sometimes weigh more than twelve pounds.

MacEnulty: What percentage of pregnant women currently give birth by C-section in the U.S.?

Gaskin: Approximately 34 percent. In many hospitals the rates of induction [starting labor through medical intervention] are in the range of 70 to 90 percent. Given the increasing maternal and neonatal death rates here, it’s imperative that we make efforts to reexamine these practices. We shouldn’t be routinely applying extreme technologies to birth without a good system for monitoring the effects.

The U.S. maternal death rate steadily decreased between 1936 and 1982. At that point it leveled off for a few years and then began rising. Women today actually face twice the chance that their mothers did of dying from pregnancy-related causes. We should be studying what’s behind this backward trend, especially since it is not happening in other developed countries. And, I must add, there simply aren’t enough planned home births — about twenty-eight thousand births per year out of a total of 4.2 million — to account for this unacceptable increase. Though home births increased 20 percent between 2004 and 2008, still less than 1 percent of all U.S. births are planned home births. But that doesn’t stop some in the medical profession from trying to use midwives as scapegoats for shortcomings in our country’s system.

Several studies have appeared in the U.S. obstetrical literature over the last thirty years that manipulate statistics to claim that home birth is dangerous for babies. Many well-designed studies from different countries, including ours, have shown the opposite results — that planned home births are quite safe for mothers and babies and manage to produce good outcomes with low rates of medical intervention or transfer to a hospital.

MacEnulty: Are there other potential reasons the U.S. maternal death rate is rising? Inadequate prenatal care? Obesity?

Gaskin: Amnesty International investigated whether lack of access to timely prenatal care played a significant part in the rising death rate and found a lot of evidence to confirm this. Assisted reproductive technologies have increased the number of multiple pregnancies, and it’s well documented that we have more diabetic women becoming pregnant than ever before. However, until we create a well-designed system for ascertaining the cause of every maternal death — something that most affluent countries did when they began providing health coverage for all their people — we’ll have to continue guessing how big a role obesity, assisted reproductive technologies, medical errors, and older maternal age play in making childbirth more dangerous.

MacEnulty: Aren’t more and more hospitals making their birth environments more mother-friendly and encouraging the use of midwives and doulas?

Gaskin: There are some wonderful hospitals that are doing everything they can to implement mother-friendly care, but the pace of these changes overall is quite slow. We still have plenty of hospitals that have never hired midwives even though we know well that midwives on staff help reduce C-section rates. The website www.theunnecesarean.com publishes the C-section rates at a growing number of hospitals across the country, so you can seek out the lowest ones. Too many hospitals give more attention to the way their facilities look than to making sure their maternity-care practices are based on strong scientific evidence. We can’t expect hospitals to change if they are not pressured to do so.

MacEnulty: What part do lawsuits — or the threat of them — play in the rising C-section rate?

Gaskin: They play a very big part and have since the late 1980s. Many obstetricians will tell you that they’re doing a lot of C-sections because of fear of lawsuits.

The initial quadrupling, from 5 percent to 20 percent, of the C-section rate between 1970 and 1980 happened in part because insurance companies issued ultimatums to hospitals that they were no longer to do — or teach — vaginal breech births. In a 1979 report commissioned by the U.S. government, a researcher pointed out that almost none of the respondents to the survey had actually been sued. Still, insurance companies decided that vaginal breech births weren’t safe. If doctors performed them, the insurer would cancel the malpractice insurance for the whole hospital. And the obstetrics community did not fight that ultimatum as it should have.

The malpractice lawsuit was invented in the U.S. because of the large number of uninsured people. The idea was that if a medical error created an expensive lifelong disability for someone who was uninsured, there needed to be some way of financing the future healthcare of that person. Now the tail is wagging the dog.

MacEnulty: Why did the insurance companies insist on C-sections if lawsuits were not really an issue?

Gaskin: When you have people who are not trained in critically reading the medical literature, they often can’t distinguish between good research and bad research, and they’ll go with whatever sounds scariest. One very unbalanced article published in 1959 by Dr. R.C. Wright helped fuel fears about vaginal breech births. Apparently his breech-delivery skills weren’t up to par. His article was the first to recommend that all breech babies be extracted via cesarean. By 2001 it was rare for a breech baby to be born vaginally anywhere in the U.S.

MacEnulty: Before C-section became so commonplace, how were breech births handled?

Gaskin: Almost all were born vaginally. It used to be that every obstetrician and family doctor who did obstetrics was required to know how to deliver breech babies. During the first few years that I worked as a midwife, the doctors at our local hospital were proud of their breech skills. I remember hearing about a twelve-pound baby who’d been born breech in good condition. Most academically trained midwives in the U.S., however, were not taught to deliver breech babies until recently. It was assumed that they would work in hospitals, where there would always be a doctor available to step in. As a result, the midwives who did know how to deal with breech birth were those who had a home-birth practice or had learned the skill in some impoverished area of the world. And after 1980 or so doctors themselves were no longer trained in breech deliveries. This put many women with undiagnosed breeches in unsafe hands when they arrived at the maternity ward: if their babies came too quickly, there might not be time to prepare for a C-section, but that would be the only option available to the doctor.

MacEnulty: How did you learn how to deliver a breech baby?

Gaskin: During our early years here at the Farm we had a mentor named John O. Williams Jr. He was one of two family doctors who provided medical and maternity services to the Old Order Amish community nearby. For the Amish, home birth has always been the norm, and they are good at it. The grandmothers did a lot of the deliveries. But when something was out of the ordinary, they would get in touch with Dr. Williams. The first time he went there for a breech birth, he explained that they would have to go to the hospital. The two grandmothers said, “Our doctor in Ontario always does breech births at home. You’re as good as he is, aren’t you?” That turned out to be his first, but not his last, home breech delivery.

At the beginning, whenever a baby was in breech position at the Farm, we would take the woman to the hospital, but the doctors there always did these big episiotomies [incisions to the perineum], which we knew weren’t necessary. One time they put the woman under general anesthesia, and then they had difficulty getting the labor going again. We felt that if we’d been with the woman, she would have stayed relaxed, and general anesthesia wouldn’t have been necessary. Eventually we had one breech baby that came too fast for us to get the mother to the hospital, and the baby literally fell into the midwife’s hands.

Breech birth can be difficult but usually isn’t if everyone is able to remain calm. The danger with breech babies is that it’s tempting to grab their feet and pull while panicked (exactly the wrong thing to do). Dr. Williams came for the first planned breech birth we performed. It wasn’t long before I was doing them while he watched. He also used to come out for twins when he could. That was how we saw our first footling breech.

MacEnulty: “Footling”?

Gaskin: That’s when the baby comes out feet first. In this case involving twins, baby number one came out fine, but baby number two was taking longer than Dr. Williams was comfortable with, so he just held the baby’s feet and gently guided him out.

MacEnulty: What can happen when doctors don’t know how to do vaginal breech births?

Gaskin: Doctors can become so afraid of assisting in a vaginal breech delivery that they might perform a C-section in a situation that is not as safe as it should be. In extreme cases the mother can even die. In New South Wales, Australia, for instance, there were three maternal deaths in 2010 stemming from elective C-section for breech presentations, and a 2007 Dutch study reported four such deaths within a three-year period. I know of two other maternal deaths that happened in the U.S. because of the mandatory C-section policy for breech babies. One of these women was a physician herself. The other was the mother of nine children, a Jehovah’s Witness, whose second twin was a footling breech after the vaginal birth of her first. She refused a blood transfusion because of her faith and bled to death during a C-section that would not have been performed twenty or thirty years ago. Her doctor was more worried about delivering the easiest footling breech possible — a second full-term twin — than about doing a C-section for a mother whose religious principles didn’t allow her to receive blood.

It’s actually insane that our obstetricians aren’t properly trained to deal with a situation that occurs in about 4 percent of all pregnancies at term, especially when most of the training could be accomplished with the use of mannequins and baby dolls and videos of breech births.

MacEnulty: The Jehovah’s Witness case seems like a rare occurrence. When women die as a result of C-section, what typically goes wrong?

Gaskin: Pulmonary embolism is one of the most frequent fatal complications. A blood clot in the leg dislodges and travels to the lungs. It can happen days or even weeks after a C-section, and often women and their family members aren’t warned of the signs and symptoms of this complication when they are discharged from the hospital. Hemorrhage, infection, and placental complications in a subsequent pregnancy are three other possible causes of maternal death after a C-section.

A vaginal birth has always been safer for the mother. The risk of death of the mother is three times greater for C-section than for vaginal birth. If we’re talking about emergency C-section only, this figure rises to four times greater. It’s a shame that any woman should lose her life because certain obstetrical skills are no longer taught.

MacEnulty: I had a C-section, and my baby was not breech.

Gaskin: Many women like yourself end up with a C-section because of perceived or real stress on the baby from their medically inhibited labors. In the seventies the use of electronic fetal monitors became routine in most hospitals. Electronic monitoring usually doesn’t work well unless the woman is flat on her back. Women used to be up walking around the maternity ward, which makes most labors move along faster. Once you have the woman lying flat on her back, she’s in a lot more pain. If she moves to get more comfortable, then the monitor indicates the baby is in trouble, and the nurses get upset with the mother for moving. This painful back-lying position can also be dangerous because of the weight of the uterus on the major blood vessels, which can interfere with the circulation of blood between the mother and the baby. Sometimes a baby can go into distress because the mother is in that position instead of on her side.

Because lying flat causes more pain, women opt to get epidurals as soon as possible. One of the side effects of the epidural is that it slows labor. If given early, it can double the length of labor.

MacEnulty: That was certainly my experience. I wound up getting an epidural, which I was told was perfectly safe.

Gaskin: Another side effect of the epidural is that the mother’s blood pressure drops pretty drastically, which means you have to expand the mother’s blood volume. That means they’re going to put in an IV, which is another device that chains the mother to the bed. So imagine you’re fully dilated, and now it’s time to push, which feels like you’re going to move your bowels in a very big way. How easy is that going to be lying on your back? They forget about gravity. You’re going against a law of nature to require all women to give birth in that position, which first came into common use even before fetal monitors. It really started when doctors began using forceps. The trouble is that this position is more often for the convenience of the caregiver than for the well-being of the woman.

We have come to believe that our human bodies are not as well designed for birth as other mammals’ are. Really it’s our brains that can pose problems: we alone among mammals have the ability to scare and confuse ourselves about birth.

MacEnulty: If we have so much information available to us regarding the safety of natural birth, why has the rate of C-section continued to grow? And how have we been convinced that C-sections are safe?

Gaskin: Birth phobia has reached a fever pitch among a large proportion of women of childbearing age. When women are afraid of vaginal birth, they actually want to believe that abdominal surgery is safer than it is. And if we see only one kind of birth, it becomes easy to think that this is the safest way. And then there’s what we don’t see. Simply put, we are allowed in our culture to see a surgical incision on television, but we aren’t allowed to see a vaginal birth in which the mother is able to move about freely and give birth in the position that suits her best. How many times do we see someone giving birth on her hands and knees on the Learning Channel? Zero, but I see it often in my practice, because it opens the pelvis and prevents certain complications. This position is common among women who aren’t taught that it’s “unladylike.” But it’s a hard position to get into when you’re under an epidural anesthetic and hooked up to a monitor or an IV.

Those vaginal births that are broadcast on TV almost always show the mother kept on her back by her IV and the electronic-fetal-monitor leads, and pixelization blurs the view of the baby being born, lest we catch a glimpse of a vagina. Women thus never get to see what their bodies can do, given a chance. What we aren’t allowed to see then enters the imagination, and fear takes over. Meanwhile my midwifery partners and I have made videos of vaginal births available since the early 1980s, including several breech births, but all our videos are considered “too graphic” for television, because they show what really happens: no episiotomy, except for one unusual case in which the baby’s testicles were coming first; no need for stitches; no active bleeding, for birth after birth. So prudishness rules out giving mothers necessary information about birth.

MacEnulty: How are C-sections portrayed in the media?

Gaskin: The C-sections that are broadcast on television make the operation look neater and easier than it often is in reality, because viewers never see or hear about the cases in which something goes wrong, never see the suturing, never see the average blood loss, never see how much it hurts to laugh, cough, sneeze, or even move when the anesthesia wears off. The programs that normalize surgical delivery also never show the public the real danger for the pregnant mother that is sometimes caused by a previous C-section.

A National Public Radio [NPR] guest writer recently blogged about how much she loved her C-section and how tired she was of feeling judged by women who’d had vaginal births. For her, giving birth vaginally brought up images of women screaming for hours on end while clutching twisted bedsheets. Many of the women who commented on the blog agreed with her and appeared to share her belief that the only dangerous C-sections are those performed in an emergency. Some were grateful that their breech babies had given them a good excuse to have a C-section, because they were terrified of vaginal birth. On the other side of the issue, a pregnant family physician wrote from her hospital bed because of complications caused by a C-section she’d had with her first birth. She faced a likely hysterectomy. But her testimony seemed not to impress those who’d had elective C-section.

This fear of vaginal delivery is something we’ve never had to face before. If we move in the direction that Brazil has, we’ll soon have a C-section rate that we won’t be able to lower, because both doctors and women will be too terrified to try anything else.

MacEnulty: I recently heard an interview on NPR about women electing to have C-sections for convenience. Some of those C-sections caused health problems for the baby.

Gaskin: Elective C-sections are a big problem. Some are performed too early because women think it’s safe to have the baby after thirty-seven weeks, even though forty weeks is average. The truth is that thirty-seven-week babies often have respiratory problems and difficulty nursing. They tend to be more susceptible to illnesses and often end up in the neonatal intensive-care unit.

This whole philosophy of encouraging women to choose C-section was promoted to a great extent by a prominent obstetrician who publicly implied that your body would be ruined if you had a vaginal birth. He didn’t come right out and say that your vagina would stay as big as the baby’s head, but he knew how to imply that. As soon as he started appearing on morning talk shows, more women started to pester their physicians to get that baby out through surgery.

MacEnulty: One woman on the radio show got an elective C-section so that her family could be there.

Gaskin: We have a generation now that tends to want to control everything, and many have been led to believe that they can control birth with the help of induction and C-section. They are not told about the disadvantages — quite the opposite. As with cosmetic surgery, people are encouraged to think it’s not a big deal.

MacEnulty: It seems that every generation faces some new issue caused by the medicalization of birth. My mother was given something called “twilight sleep,” and she often talked about how she felt cheated out of her birth experience. What was twilight sleep, and what happened to it?

Gaskin: Twilight sleep was a combination of morphine and scopolamine, an amnesiac drug. It replaced chloroform and ether, both of which were abandoned because they sometimes killed people. After the morphine from the twilight sleep wore off, the woman wouldn’t be able to remember her labor or the birth. One of the side effects was that women weren’t competent to take care of their babies right away. This helped create the practice of separating the mother from the newborn, which worked to the benefit of the dairy industry and the formula companies. Formula-feeding was presented as more scientific than breast-feeding. Some people still think breast-feeding is disgusting because it’s a bodily fluid, forgetting that it is the only food that is perfectly designed for human babies. There’s a lot of money to be made off women’s fear of their bodies and reproductive processes — not to mention their insecurities about their attractiveness.

MacEnulty: Tell me about the Gaskin maneuver.

Gaskin: Our international development organization, Plenty, sent many volunteer carpenters, farmers, and soy technicians to Guatemala in 1976 after a major earthquake had caused much loss of life and property damage. I spent a few weeks there and met the formally trained district midwife, whose job it was to supervise the traditional midwives. She’s the one who told me about the locals’ way of dealing with the feared complication called “shoulder dystocia” — when the shoulders become wedged and stuck in the mother’s pelvis after birth of the head. The traditional method was more effective than what this midwife had learned in her academic training: they would simply help the mother get up on her hands and knees, thereby enlarging the pelvis and freeing the baby’s shoulders.

MacEnulty: Why are our physicians so lacking in basic knowledge about delivery?

Gaskin: Because we were the only country that decided to eliminate midwifery more than a century ago. When midwifery is gone, or so marginalized that midwives have little or no part in teaching medical students about normal birth, birth practices can rather quickly become surprisingly brutal. More dumbing down came with the rise of C-sections during the late 1970s. In the early 1980s I was in North Carolina at a teaching hospital, and I was about to show a roomful of obstetrics residents a video of a breech birth that had happened at the Farm. Just before the video began, the chairman of the department whispered in my ear, “Do you realize that you and I are the only ones in this room who have ever seen a vaginal breech delivery?” I was shocked. This was how I discovered that it was assumed you had to perform a C-section for a breech delivery. It didn’t matter if the baby was coming fast, and the infant and mother were fine, and the doctor performed perfectly. The higher-ups would still reprimand the doctor, or worse. Obstetrics is a strange field in which an expert can be punished for doing a good job.

We were the only country that decided to eliminate midwifery more than a century ago. When midwifery is gone, or so marginalized that midwives have little or no part in teaching medical students about normal birth, birth practices can rather quickly become surprisingly brutal.

MacEnulty: Why isn’t this a problem in other countries?

Gaskin: It is a problem in some. We’ve already mentioned Brazil. By 2000 or so, private hospitals there were boasting 95 percent C-section rates. I witnessed an elective C-section in one of these hospitals, and I can report that both the young parents were terrified of the surgery, but they were even more scared of having a vaginal birth, because it has become such a large unknown. Mexico, South Korea, Thailand, Turkey, Puerto Rico, and Chile also have extremely high rates of C-section. On recent trips to Australia and Japan I’ve seen how those countries are imitating some of the excessive birth interventions that are practiced here, under the mistaken impression that our maternal death rate is lower than theirs.

At the same time, Scotland, the Scandinavian countries, and the Netherlands have managed to keep their C-section rates low, and their maternal death rates are some of the lowest in the world. It would be possible for us to imitate them, but we’d first have to make some big changes in how we think about birth and how we treat mothers and their babies.

It’s worth pointing out that in other Western-style democracies, health-insurance companies are not profit-making institutions. Here, that’s what they are, first and foremost. U.S. insurance companies don’t have to think about public health, so they don’t.

MacEnulty: How is it profitable for insurers to force hospitals and doctors to do a procedure that is more expensive and more deadly?

Gaskin: Insurance companies don’t have to reduce expenses; they can set their premiums as high as they like in order to make a profit. That’s the problem. And because data on maternal mortality and trauma are so poorly gathered here, it isn’t as easy as it should be for people to protest policies that force pregnant women to undergo dangerous medical interventions — policies designed to put the priorities of hospitals, insurance companies, and doctors above the best interests of mothers and their babies.

It’s a well-kept secret that the U.S. maternal death rate has been rising since the 1990s. In 1970 it was 7.5 deaths per 100,000 births. In 2008 the rate had risen to 17 deaths. In California the maternal death rate tripled between 1996 and 2006. For women of color death rates are much higher. The New York Academy of Medicine reported that the maternal death rate for African American women in New York City was an incredible 79 deaths per 100,000 births. And yet our national goal since the late nineties has been that no more than 3 women per 100,000 live births should die.

And these numbers don’t even address the inconsistent and incomplete way that maternal deaths are recorded in our country. For starters, we have an honor system. We don’t even require every state to gather maternal-death information in the same way. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] has designed a U.S. Standard Certificate of Death with five questions meant to pick up a possible maternal death, but the CDC doesn’t have the power to make this death certificate mandatory, so about a third of the states refuse to use it. Epidemiologists, midwives, and doctors in other countries find this incomprehensible.

I get my data from CDC documents and compare them with the data-gathering bodies from other countries.

MacEnulty: I’m surprised that some of our cities have higher maternal death rates than much poorer countries. How can this be?

Gaskin: Let’s look at Costa Rica and Cuba, two countries in our own hemisphere with lower maternal death rates than ours. Both countries manage to get all their pregnant women into prenatal care, whereas in the U.S. a large proportion of expectant mothers have trouble accessing prenatal care early in their pregnancies. Both countries emphasize prevention and good preparation for birth and perform C-section only when medically necessary. Epidurals aren’t routine, and midwives and nurses still know how to calm a laboring mother without drugs. Both countries consider healthcare coverage a right, not a privilege, and both have better reporting systems for maternal death and injury than we do, so their doctors are better informed about the dangers of too much medical intervention in birth. We have very few midwives in the hospital system here. In most countries with better outcomes than ours, midwives far outnumber obstetricians and maternity nurses combined. We substitute technology for people, and technology cannot calm fears during labor. Fear produces adrenaline, which can slow or even halt labor.

MacEnulty: You’ve described the experience of having your first baby in a hospital in the 1960s as “horrific” and “demeaning.” They apparently gave you anesthesia without your consent.

Gaskin: Like two-thirds of U.S. women in the mid-1960s, I had a forceps delivery. I felt as if I’d been assaulted and then asked to pay for it. In those days there was no concept of informed consent. The view was that if you went to a hospital, you had already consented to whatever they wanted to do to you. I had a caudal, a type of spinal anesthesia that is no longer considered safe, when I wasn’t even in pain. They were going to do that forceps delivery whether I needed it or not.

MacEnulty: How can we make labor and birth work better?

Gaskin: I like to teach women that their bodies rock! Our bodies produce oxytocin, a hormone that helps birth progress. It is harder for laboring women to produce enough oxytocin when they are frightened, and this is where midwives and doulas become important players in the birth process. Women produce the most oxytocin when they are in a trance state, so low lights, few interruptions, and loving words and actions help. Women’s bodies also produce endorphins, which block the perception of pain, and this effect is stronger when they receive loving, considerate care. We need a lot more midwives and doulas in the U.S.

I also teach women that their cervixes function like sphincters: They don’t open as well in public as they do in private. They don’t like being yelled at. They open better when the mouth and jaw are relaxed. Laughing and smiling as much as possible during labor helps to increase the level of endorphins and thus pain relief. When a laboring woman discovers that she can confront fear with laughter and wipe it away instantly, she has learned something that will strengthen her for the rest of her life. I find that coarse humor about bodily functions can be enormously helpful. Singing and moaning also help, whereas whining doesn’t.

I tell women that vaginas have a similarity to penises in that both can change size enormously. For this to happen, the person must not be frightened. Vaginas can even change shape temporarily if necessary. After the baby has passed through, the vagina becomes small again, like the penis after an erection. A vagina can’t stay open after birth any more than a penis can remain permanently erect. Midwives have been able to learn these wonderful secrets by observing women in labor.

MacEnulty: Do you believe that home births are safer than hospital births?

Gaskin: For some women the answer is yes; for others, no. Women with insulin-dependent diabetes should give birth in hospitals. But a healthy woman who lives in a society with a C-section rate as high as ours might actually be safer with a home birth, depending upon the availability of good midwife care in her area and good teamwork with the professionals at the local hospitals. I think that women, wherever they live, ought to be able to choose birth at home, in a center, or at a hospital. The British Medical Journal published a study of all births attended by certified professional midwives in 2000. It found that planned home births were just as safe as hospital births and had fewer medical interventions and problems.

It is now legal in only twenty-seven states for certified professional midwives to attend home births. I look forward to the day when such legislation will be passed in the rest of the states. Women who prefer hospital births have nothing to fear from this.

MacEnulty: I don’t think that it even occurs to most women today to expect loving, knowledgeable support during the birth process from anyone outside of their families.

Gaskin: I don’t know of a single obstetrics or maternity-nursing textbook that mentions the importance of love and compassion in the care of women during labor and birth. I remember a sweet obstetrician from Pennsylvania who told me in the late 1970s, “They’ve taken all the joy out of this profession.” I didn’t really understand then what he meant, but now I do. During the 1990s there was a shake-up in maternity care. Hospitals spent lots of money improving their facilities at the same time that they were downsizing their nursing staff. Nurses had to care for more women at once than they had done previously, and they began to spend more time doing paperwork and tending to various machines. Today a common occupational hazard for nurses is urinary-tract infections, because they often don’t even have time to go to the bathroom.

MacEnulty: I used to joke that in South Florida, where my daughter was born, if you didn’t have the baby in the car on the way to the hospital, you were going to have a C-section. I didn’t know any woman among my peers who was able to have a vaginal birth in the late 1980s and early nineties.

Gaskin: In the seventies it wasn’t unusual for a woman to have a twenty-four-hour labor. Then came the whole concept of “active management of labor,” which began at a hospital in Dublin, Ireland. First they wouldn’t admit you unless you were in true labor, and if you didn’t dilate at the rate they wanted you to, they would stimulate your labor with oxytocin. They could pretty much guarantee you’d have the baby within twelve hours. But at least they had midwives, and there would always be somebody with you. When the concept was transferred to the U.S., they didn’t have somebody with the woman at all times. Instead there was a strip of paper to show the baby’s heartbeat. This is why the doula has become such an important figure in maternity care today. Every woman giving birth in a hospital should have one.

MacEnulty: I thought when the Lamaze method became popular, the man or partner was supposed to be there to give support.

Gaskin: That concept worked as long as there was some sort of preparation. After my book Spiritual Midwifery came out, a lot of couples wanted natural childbirth, but they still wanted to do it in the hospital setting. What they hadn’t counted on were all the rules. You weren’t allowed to get out of bed or drink water, and sometimes an ill-prepared partner would get scared or frustrated and maybe get kicked out. There were enough bad experiences to create a backlash.

MacEnulty: So how should it happen? How can birth be the beautiful, positive experience that you describe in your book?

Gaskin: Look for a good doula if you are planning a hospital birth. Refuse to listen to negative birth stories, no matter how much someone wants to relate one to you. Go to YouTube and type in “the dramatic struggle for life” to watch an elephant in Bali have her 250-pound baby and then resuscitate it. Realize that she didn’t take a course or read a book in order to know how to do this. Then type in “attica zoo chimp birth.” Now you can watch an experienced primate giving birth in her own special way (in captivity, which we could equate to a human birth in a hospital). She has a doula with her. Notice how careful the doula is to avoid violating the laboring mother’s space while she pushes her baby out. Notice how no one yells at her or tells her what position she should be in. Notice where she puts her thumbs as she labors, because this helps her vagina to open. Notice how her position actually slows down the birth of her baby’s head so that she avoids any laceration or discomfort.

MacEnulty: You’ve written about the “mystic beauty of the laboring woman when she’s not being harassed.” We don’t usually think of a woman giving birth as beautiful no matter how much lip service we pay to the “miracle” of birth.

Gaskin: I got to see that mystic beauty at my very first birth. The woman was in an ecstatic state. Having that as my standard led me to try to help maintain that radiance in every laboring woman, and that turned out to be a formula for safety. We could always tell if there was a problem during a labor because this quality of mystic beauty wasn’t there. When it was missing, we would act quickly and get Dr. Williams.

After our first four hundred births, our C-section rate was only 0.5 percent, and this wasn’t because we kept people from using our maternity services if we thought their hips might be too small or their baby’s father too large. In my years of traveling I have become aware of at least three other midwifery services, backed by supportive physicians, that had C-section rates that were almost identical to ours. One is an ongoing midwifery service in Okazaki, Japan, which functions under the guidance of Dr. Tadashi Yoshimura. He came up with the phrase “mystic beauty.” When I heard him say that, I thought it was the perfect way to describe the look I often see on a laboring woman when she’s not afraid and is not fighting her body or being oppressed by unrealistic expectations imposed by those around her.

I talk to a lot of heartbroken widowers. They didn’t know this could happen! The rising maternal death rate is a national disgrace that we have been sweeping under the rug for more than a decade.

MacEnulty: What are the current birth statistics for your center?

Gaskin: We published a preliminary report in Birth Matters. At that time we’d accepted a total of 2,844 women for care. Out of that number almost 95 percent of the births were completed at home, while about 5 percent were in the hospital. We had ninety-nine breech births and seventeen sets of twins. We’ve had no maternal deaths. Our neonatal mortality rate is 1.7 deaths per 1,000 births.

There is no way that a bunch of liberal-arts majors, with the support but not the constant presence of mentoring physicians, could attain such good results if there were something inherently wrong with the design of women’s bodies.

MacEnulty: How does this compare to hospital neonatal mortality rates?

Gaskin: Very favorably, and those figures include babies who died after transport to a hospital. Our statistics also show a very low rate of premature birth, presumably because we were able to give mothers good nutritional counseling during pregnancy.

MacEnulty: What percentage of expectant mothers in the U.S. use a midwife?

Gaskin: Around 10 percent. In Germany the figure is 100 percent. Why? Because there’s a law there that a midwife must be present at every birth. Here in the U.S., far more women would choose a midwife if one were available to them, but with so few working in this enormous country, most women don’t have that choice.

That’s why I wrote Birth Matters. I want everybody — grandpas, grandmas, aunts, cousins, teenagers, dads, husbands, brothers — to understand the dangers. If the maternal death rate is going up, it affects the whole family, and also friends. I talk to a lot of heartbroken widowers. They didn’t know this could happen! The rising maternal death rate is a national disgrace that we have been sweeping under the rug for more than a decade.

MacEnulty: What about an expectant mother who lives in a place where there is little or no midwifery? Are there things she can do that would increase her chances of a positive hospital birth experience?

Gaskin: Women who find themselves in the position of going to a hospital in an area where there are few or no midwives would be wise to find a doula who has a good record of helping women avoid C-section. It also seems to shorten labor if women do a few deep squats every day during their pregnancies.

MacEnulty: What role can men play in the birth process and in changing these attitudes?

Gaskin: Dads have a very strong urge to protect their partners, but there is now so much confusion about birth that many think high-tech medical intervention provides protection. It isn’t immediately obvious to a man how a baby can come out of there, but I explain to them that a woman’s body works as logically as a man’s does. I also help them understand the importance of the mind-body connection and the environment of the hospital, where the woman often doesn’t have a midwife who stays with her, where she has time limits and may be dehydrated or overhydrated — all these things can cause complications. Men’s instinct to protect is good and important, but their role is to understand their partner’s body and not have an unquestioning belief in fancy technology when nature’s way is working well. You can’t design a vagina to work more efficiently. It is as fancy as it gets.

MacEnulty: You titled your first book Spiritual Midwifery. Would you describe the work you do as a midwife as spiritual?

Gaskin: I think of the story told by a couple whose baby had just been born in their rural home. They were sitting on their bed, cradling their baby, and they noticed that the neighbor’s cows had walked up to their house and were looking in the window. Cows don’t ordinarily do that, you know.

There is an energy associated with labor and birth. Birth is holy and sacred. But you have to be respectful of mother and baby, or you’ll miss it. If we come to it with a sense of awe and treat the mother with kindness and respect, birth can be a truly spiritual, empowering experience. As a society we can choose to treat it that way, or we can look at it as a way to make money and simply get babies out of their mothers as quickly as possible.